Vermont Folklife, much like museums, libraries, and historical societies, often serves as a bridge between schools and other learning spaces that want to bring community members and their life experiences into their classrooms. We have learned over time that these requests are often asking for resources, services, and activities that go beyond a roster of community speakers. In many cases, we act as a sounding board for educators who are looking to make this invitation with sensitivity and care, especially because this is a new, potentially anxious experience for all involved. We find that educators want to identify toolkits and methods to support students’ abilities to listen, observe, and document their experience with guests who share their stories. Just like reading a textbook requires a certain literacy and skill set, so does engaging with community narratives that can come in multiple forms–from local lore to foodways, images, and artifacts that document a place or occupation and to secondary sources that share and represent community stories.

Learning with, and from, individuals in our community, and the careful documentation of their life experiences, is at the heart of this kind of learning. What questions to ask, how to ask them, and managing recording equipment are all important pieces of an interviewer’s skill set. They take time and practice to do with ease and comfort. But we also remind learners that how you treat an interview participant is an important skill, the one that all these other abilities hinge on. We advocate for the mutual benefit (what is referred to as reciprocity) of the interview experience. Gestures like sharing the recording or offering a role of collaboration or feedback in the classroom’s interview project are one way to continue the commitment to the person who shared their life story. We like to think that an interview done well reflects and records a bond of trust and respect between interviewee and interviewer, between story teller or sharer and story receiver. Folklife collections and oral history interviews are one method of inquiry that can sharpen a focus on members of a classroom’s larger community. The interview clips and learning activities featured in the Teaching with Folk Sources Curriculum Guide showcase how primary sources are in fact a type of collaboration and an invitation to expand what is “folklife” and who gets to be a part of it.

Folklife, a type of inquiry that focuses on “ways of life” as its central lens, is constantly changing. Rather than focus on cultural loss or salvaging, folklife inquiry is more powerful when it is positioned to offer insights about human experience through the sharing of personal lived histories in safe and supportive environments.

Classroom Reflections: Making Primary Sources Relevant to Students

Don Taylor, Sustainability Teacher, Main Street Middle School, Montpelier, VTI noticed that students were very good at analyzing artifacts and connecting their observations to perspectives on life in Vermont. Students had some very interesting ideas about the issues, habits, and “ways of life” that make Vermont unique.

Additionally, the interviews of sugar makers conducted by other middle level students (see the Ben Robb and Maple Sugar Interview podcast produced by Brattleboro Historical Society and Brattleboro Area Middle School) were very impressive and provided my students with models for how to interview community members.

Before I engaged with this curriculum, I believed that studying ethnography and ways of living in Vermont might be too complex for my students, but now I see how it could be deeply integrated into our programming.

Tapping into Community Knowledge: Folklife as Challenging History

A common request or suggestion we receive from educators and members of the public is to record the stories of local elders. Likewise, curricular materials often propose interviewing grandparents, family members, or friends with a life experience a few generations apart from students. There are a number of strong reasons this invitation is a natural and approachable way into a project that features interviewing skills. An elder has more life experience to reflect on. They might have been prompted to talk about their life history before or feel prepared to share it publicly. They may have lived through events or participated in a way of life that has made it into history books and documentaries. Sometimes these interviews carry urgency: They may not always be around or in the position to speak about their lives that far into the future. For youth and elders, an interview is a rare and mutually enriching opportunity to learn from each other.

We understand and often follow this impulse. One interview collection at Vermont Folklife serves as illustration. Daisy Turner (1883-1988), an African American woman who lived in Grafton (southwestern Vermont), was a gifted storyteller and was a skilled rememberer. The interviews present her and her family’s history, including details of her father’s early life as an enslaved person and later a soldier in the U.S. Civil War, a timeline that spans from the 1880s to the 1980s. One person’s life can act as a time machine, a vehicle of preservation. Ms. Turner, and the nearly 60 hours of interview recordings she sat for, demonstrates how oral information can be passed on and how historical perspectives, when told through an individual’s life, can move backward and forward in fascinating and dynamic ways.

As we see it, this type of interview request also carries an embedded assumption: that one person, particularly an elder, can be a repository of their family’s folklore and local legends, jokes, songs, and cultural knowledge more broadly. While this can be true, we believe that a person’s stories are parts and pieces of their wider lived experience. We think it is important to resist treating stories as things or something to be collected, or worse, extracted. This position is influenced and shaped by storytelling concepts, techniques, and approaches developed by Indigenous communities in Canada and the U.S. Oral knowledge in these cultural contexts is almost always socially reinforced in the telling: “Indigenous people who grew up immersed in oral tradition frequently suggest that their narratives are better understood by absorbing the successive personal messages revealed to listeners in repeated tellings rather than by trying to analyze and publicly explain their meanings” (Cruikshank 2005, 60). Cunsolo Willox, Harper, and Edge (2012) argue that these methodological concerns should be part of our foundational ideas about research and interviewing, particularly for situations with historically imbalanced power dynamics. In the context of digital storytelling projects in Rigolet (Northeast Canada), they ask: Can researchers or interviewers take on the role of listeners and shift away from the role of collector or gatherer and then “story re-creators” (2012, 142)? Being a listener in this way follows the lead of cultural systems that have a developed, active understanding of how to attend to oral knowledge in ways that Euro-American academic sciences of inquiry and reporting, and their theories on knowledge (their epistemologies) are less equipped to do.

The lore of folk is one of several important entry points for tapping into folklife and expanding into the fuller context of a person’s lived experience. Here are a few definitions and descriptions that ground this term.

Folklore is the combination of two words–folk, which means people, and lore, which means knowledge. Folklore is a special knowledge of the people that is passed down from generation to generation or that holds groups or communities together.

Beverly J. Robinson (Kinsey-Lamb 2020, 13)Folklore provides a useful framework for thinking about our cultural practices: What do we do, know, make, believe, and say? If “culture” is what we do, how do we perform ourselves on a daily basis? What social practices and meanings have we inherited?

Bonny McDonald and Alexandria Hatchett (2021, 76)What is traditional culture, or folklife?

How is culture retained?

How are cultural traditions passed on?

How does culture change?

How do people carry culture with them to new places?

What is your favorite holiday/festival/special family occasion?

What is your favorite thing to eat during these occasions?

What are special sayings that your family uses?

Michael Knoll, Tina Menendez, and Vanessa Navarro Maza (2020, 88)

A folklife topic is a way to create discussions around existing narratives and assumptions about local place and identity. The American Folklife Center, a division of the Library of Congress, houses many collections that feature occupational folklife, ranging from small business owners to factory workers, doctors, electricians, grocers, social workers, food service employees, health care staff (see Occupational Folklife Project). Occupational folklife is a rich entry point for creating culturally relevant pedagogy, particularly relevant for young people who have jobs and are exploring their professional interests.

Here are some definitions and perspectives that reflect the oral history and ethnographic approach to interviewing.

Interviews are the keystones for great stories that encourage us to think, feel, interact, or take action.

Carol Spellman (2019, 4)Oral history . . . refers [to] what the source [i.e., the narrator] and the historian [i.e., the interviewer] do together at the moment of their encounter in the interview.

Alessandro Portelli (Shopes 2020)I want to understand the world from your point of view. I want to know what you know in the way that you know it. I want to understand the meaning of your experience, to walk in your shoes, to feel things as you feel them, to explain things as you explain them. Will you become my teacher and help me understand?

James Spradley (1979, 34)

Our interview projects with people who work in Vermont’s agricultural sector is an avenue of study that has yielded important opportunities to view rural life and livelihoods in a new light. Topics include the highs and lows of multigenerational family farming, the pressures and resilience of migrant workers from Central America, the experiences of homesteaders trying to make it in small-scale agriculture. These topics and themes are represented in excerpts and transcripts, part of this project’s Teaching with Folk Sources database, and were arranged to challenge assumptions and narratives about Vermont’s status as an agricultural haven. We wanted to know: How do narratives reflect, magnify, obscure how people understand their lives today? How do these ideas change or differ based on your life stages? How can folklife topics like farming and foodways, or other forms of occupational life, generate inter-generational conversations?

Classroom Reflections: Making Primary Sources Relevant to Students

Joe Rivers, Social Studies Teacher, Brattleboro Area Middle School, Battleboro, VTI noticed that students appreciated lessons presented in various ways: video interviews and presentations, audio interviews and podcasts, slideshow presentations, primary source text (i.e., newspapers, newsletters, etc.).

I heard students talking about a time when they stuck up for themselves or acted as an ally for another. It was the opening activity in the interview unit (see What Is Good Listening? Activity). Students paired up and attempted to practice interview strategies we had brainstormed after watching the Ruby Sales interview on the Library of Congress site. The strategies included ice breakers, open-ended questions, follow-up questions, nonverbal signs of interest by the interviewer, speaking clearly, and wait time. It was informative to observe and listen to the process.

I learned students come to speaking and listening skills with various levels of competence that don’t necessarily match their reading and writing skills.

I used to think that my primary task was to practice the skills of reading and writing, now I think I should also focus more on other means of learning and sharing information that includes audio, video, speaking, and listening techniques.

Developing Interview Skills: Learning to Listen for Viewpoints

Another request we get is to offer advice and training on how to do an interview and what questions to ask. A lot of stock is placed on coming up with the “right” questions to ask to receive specific answers and information. In some ways, this expectation is rooted in journalistic practices of interviewing: the Five W’s and H – Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? These questions can guide an interviewer to pull out key facts of an eyewitness account or perhaps to create an unbiased description of a complex topic. These are important abilities to develop in students and for all learners. These learning goals also reflect ideas about how knowledge is created and recorded. The early foundations of the historical discipline as an empirical science argued for the faithful presentation of the past and objective reality that is grounded in facts, “the past as it actually happened” as famously stated by the 18th -century historian Leopold von Ranke (Paricio 2021, 114).

But what if events or happenings are told partially and through only one person’s or group’s perspective? The Rashomon effect, based on Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashomon (1950), is a term that describes the fragile and unreliable nature of human observation to report “objectively.” The film is a story of how multiple tellings of the same encounter lead to significant differences and disagreements about the facts as they happened. Multiple perspectives, and with them aspects like interpretation and point of view, emerge as a foundational part of how historical knowledge is built. Encountering and learning with primary sources like personal diaries and recorded testimonies often serve as evidence to disrupt or contradict versions of events accepted as the dominant narrative. Learning activities on the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, featured in the Teaching with Folk Sources Curriculum Guide, present how this history was largely erased from Oklahoma and national history for much of the 20th century. When it was mentioned in historical and popular literature, it was referred to as a race riot or race war, which illustrates how the act of naming reflects specific perspectives represented, absent, or contested (Nowell 2008).

When you center a person as a primary source, questions work best when they magnify how that person sees the world–their perspectives, viewpoints, even interpretations of reality as they live it. We often advise posing questions about their biographical facts like where they grew up or where they live today. This initial set up signals to them that the facts of their life are worth knowing about and learning from. This signal is subtle but powerful in its simplicity.

An oral history interview is one important method for generating this kind of person-centered knowledge. Sometimes we refer to it as a long-form interview because it can sometimes feel like a long and meandering road. Sally Galman (2007) contrasts two interview modes or attitudes: mining and traveling. One is focused on looking for a thesis or topic sentence in an interviewee’s responses. The other is committed to exploring where the interview goes, which might include changes to the prepared questions. In some ways, you can think of an oral history interview as an exercise that is the backward design of a person’s life. Unlike a Wikipedia page, a person’s life is rarely laid out in a clear linear progression.

Listening to how interviewers ask a question can be as useful as hearing the responses it generates. In the Teaching with Folk Sources database, clips in the primary source sets include the back-and-forth mode of questioning that is a feature of an oral history interview.

Transcript of 1988 interview with Euclid and Priscilla Farnham, Tunbridge, VT, conducted by Gregory L. Sharrow (link to audio excerpt here)

00:01 Greg Sharrow (GS): So you haven’t necessarily made a conscious effort to, um, not change. But then again, you haven’t courted changes that didn’t seem …

Priscilla Farnham (PF): He’s done what was expedient.

Euclid Farnham (EF): Yeah, we have. We certainly have changed it in some respects, we certainly have changed. When my dad, my dad bought this fifty-five years ago, and when he came, the milk was cooled in an outdoor water tub, which was nothing more than cold water coming from the spring. And you put the cans and these were all the old milk cartons. You put it down into the water and cool it. And then after a few years, they they built a small milk house and put it in a nice bank milk cooler, which again, all you do is put the cans in with some ice water to cool it. And then, of course, a few years ago we advanced to bulk tanks, which certainly was a tremendous advancement in the quality of milk.

00:59 GS: And that was, there was no way around that, was there?

EF: Absolutely no way around that. You had to do this or go out of business, and a lot of especially older farmers did go out of business.

01:08 GS: Yes, it seems to have been a…

EF: Cut off.

GS: Yeah.

EF: Absolutely. That’s when the numbers dropped drastically, especially in this area. Orange County area, the farms are basically small. Go over in Addison County, it’s not uncommon to see 100, 150, or even 200, but in Orange County, it’s very rare to see. A large herd here will be 50 or 75.

01:35 GS: Was it during your working lifetime that a transition was made from horses to tractors?

EF: Yes. Yes.

GS: So you grew up working a team?

EF: Yes, we had a team. In fact, the horses, the last three died there on the farm, and two of them were well over 30 years old. My dad wouldn’t sell them, and he said they’re just going to stay here as long as they live and die here, and they did, they’re buried here. We did. When my dad came here, he had oxen and then he started using horses because a horse has a much longer lifespan than an ox does.

02:09 GS: So could he use oxen for mowing and things like that?

EF: Oh yes.

GS: Oh for heaven’s sake.

EF: Mm-Hmm. Mm-Hmm.

The structure and atmosphere of oral history interviews are designed to be tailored to the needs and preferences of the individuals being interviewed. The Journal of Folklore and Education issue “The Art of the Interview” (Sunstein 2019) features several commentaries and resources for modeling interview projects for educators and students. “Using Formal Interviews to Build Understanding in Social Studies” by Nate Grimm outlines one template for introducing and scaffolding student interview projects in a high school setting. “See Tell Me What the World Was Like When You Were Young: Talking About Ourselves” by Simon Lichman and Rivanna Miller offers approaches for integrating intergenerational topics and dialogue in the interview format. “Bridging Cultural Gaps Through Interviews” by Raymond M. Summerville features discussion about the experience of selecting excerpts and editing interview recordings.

And don’t forget the artifacts! While we push against the idea of “stories as things,” physical objects from a personal life can serve as a great way to kick start conversations and memories. And artifacts are an important part of folklife (see HistoryMiami Museum’s F.A.C.E.S object-based learning approaches in Unit 3 as an entry point).

Classroom Reflections: Teaching with Spanish Language Recordings

Mary Rizos, Middle and High School Spanish Language Teacher, Rivendell Academy, Orford, NHSomething [about the curriculum] that aligns so well with a second language classroom is the idea of expanding our view of community by incorporating more perspectives. That’s almost the entire purpose behind teaching people other languages.

When we are babies, we spend every day, all day, listening to people talk, and two years pass before a baby can begin to use that language themselves.

A middle school or high school student, in contrast, will spend five hours a week for a year or two, or maybe even three or four, in a second-language-learning environment, but even then is likely still hearing English more than the language they are there to learn.

So, what, then, are we actually teaching? Can a student learn a language in high school? Yes. Well enough to speak it where that language is spoken? Yes. Is this typical or a sure thing? No.

In response to a combination of materials including the Spanish-language recordings provided, one student said something to the effect of “We’re not doing anything wrong, it just takes time.” So that’s something I thought was a really good reflection, and it’s something so hard to “teach” students about language, just that it takes a lot of listening and time and misunderstandings–there’s nothing wrong with that process; that’s the process working correctly. I think using these materials and reading a student reflection reminds me as a teacher too that I don’t provide enough of that kind of challenge for students to engage in, get used to, and build up their skills, tolerance, and endurance for. We do a lot of listening to songs, but not enough listening to different native speakers of Spanish.

Like open-mindedness, perspective-taking is a skill that can be learned and practiced. Learning another language is, at its most basic level, a reminder that not everyone does things the same way or lives the same way, and that learning about that enriches rather than diminishes our own experience.

Using these materials, particularly with my 10th-grade students, did a lot for me in terms of how I understand their lives and their experience here.

Sharing these materials with 10th-grade students led to discussions about othering, about a farmer’s use of “them” and “they” quite a bit (see “The Community…Accepts Them”). Students articulated their discomfort upon hearing those terms and connected that discomfort to their own experiences working locally at an inn with people who were not native English speakers. What my students shared was 1) that experience with their coworkers is the only time in their lives they’ve shared an environment and engaged with non-native English speakers, 2) they were initially quite nervous and worried about not being able to understand their coworkers and vice versa, 3) they learned how to adapt and communicate and recognize it as a skill that they will bring with them into other similar situations and in those situations they will feel much less discomfort and concern, and 4) the students shared that they were often hesitant to ask questions about where people who were not native English speakers or clearly not local were from or other information about them because they were afraid of “getting in trouble,” of facing a backlash for being wrong.

Being able to have this window into my students’ lives and perspectives is very valuable for me as their teacher, and as a teacher of students like them. I can’t envision where else in our school days or year this conversation would have come up in quite this way or with quite this level of reflection and transparency. Using these materials as a starting point generated curiosity and connections that allowed us to think about both language and community in a really critical and reflective way.

Concluding Thoughts: Oral History Interviews Challenge How and What We Learn

Folklife topics and oral history interviews offer a conversation with the communities we are a part of. They can localize what is presented as the official record or dominant narrative–sometimes offering a critique or counternarrative. This lens and method of inquiry includes and values multiple viewpoints, perspectives, and even opinions–the “who” part of the telling of history. It inserts important questions such as “who” authors the record that shapes the narrative you adopt? And who is not included and why?

These gateways to local learning can introduce and spotlight ideas of knowledge construction– he “how” we know what we know. If our records are partial, if events can be viewed and interpreted from multiple points of view, how should we be evaluating sources? Who is doing the collecting? What factors determine what is selected?

Lastly, learning with (and, when fortunate, co-creating) primary sources is a democratic and potentially empowering act: Having access to the materials and records that tell the story of your community, or to recognize the absence of the records, can be a powerful encounter.

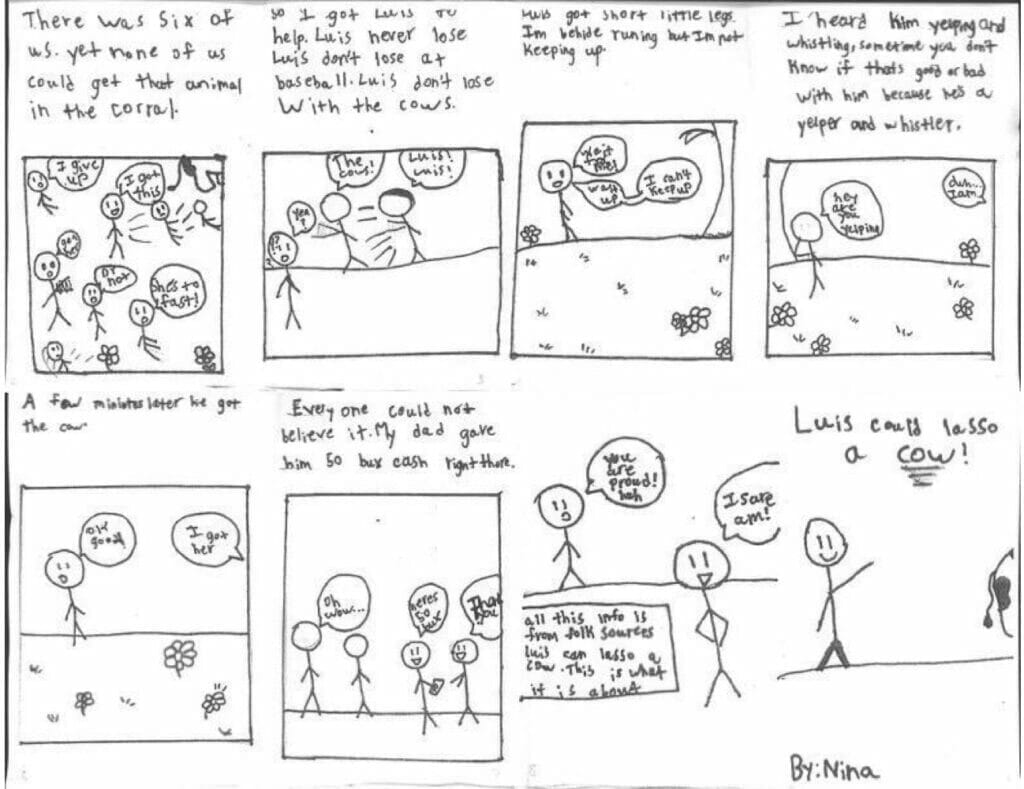

Classroom Spotlight: Making Mini-Comics with Primary and Secondary Sources

Kathleen Grady, PreK-Grade 5 School Librarian, White River School, White River Junction, VT

In July 2022, I took a course through Vermont Folklife: Field Methods for Documenting Everyday Life. Through this course, I became aware of The Most Costly Journey, a recently published comic anthology based on ethnographic research. I also learned about Vermont Folklife’s exhibit The Golden Cage, which was based on interviews conducted by former migrant educator and current high school teacher Chris Urban. These details inspired me to tackle a project focused on primary source materials that connected Vermont stories about migration with my 4th– and 5th-grade students.

The project was anchored by this guiding question: How might telling (or listening to) a story help someone who is going through a hard time? My hope with this project was that my students might consider storytelling in a different light. Many understand storytelling for its entertainment value, but the therapeutic value of storytelling was a new concept for many of them.

This project addresses certain AASL (American Association of School Librarians) Standards, such as “enacting new understanding through real-world connections,” demonstrating “empathy and equity in knowledge building within the global learning community,” and “generating products that illustrate learning”.

To build background knowledge on the subjects of migration and Vermont stories, we read aloud some of the first chapters of Julia Alvarez’s Return to Sender (2009). The middle-grade novel is told from two perspectives—that of the farm owner’s child and the daughter of a Mexican farmworker hired to work on the farm. Our 5th graders had recently finished reading Esperanza Rising by Pam Muñoz Ryan (2002) and had considerable background knowledge about migration from Mexico to the U.S. and the plights of farming families. We also examined some photographs from the Golden Cage project, which inspired Alvarez’s Return to Sender.

Some months later, we began a standalone unit on the concept of primary source. For these lessons, I used images from the Library of Congress that addressed the problem of child labor in the early 1900s. We had recently read aloud Mother Jones and Her Army of Mill Children to build background knowledge. To introduce the concept of primary source, I used a lesson from Stanford History Education Group (n.d.) which asked the students to consider a food fight and whose perspective on the incident they would like to read to inform themselves. The food fight lesson grabbed their interest and attention and helped them connect quickly to the relevance of primary vs. secondary sources.

Student comic based on interview excerpt Interview Excerpt – Vermont Dairy Farmer: “Luis could lasso a cow,” Folklife Primary Sources Repository.

We closely examined two of the comics: “A New Kind of Work: The Story of Delmar” and “Now That I Have My License: Reflections on Driving.” I carefully chose stories that I thought would resonate with my students. Before we read the stories together, we reviewed some basic geography, such as the route between Chiapas, Mexico, and Vermont. Our Spanish teacher, Natalie Chaput, collaborated with me on the unit. With the students, we reviewed some of the key vocabulary, the geographic routes between Chiapas and Vermont, and read passages from the Spanish version of the comic anthology El Viaje Mas Caro. We used a summarizing graphic organizer titled “Somebody Wanted But So Then” (Smekens Education 2018) that helped my students break the story down into smaller parts.

With background knowledge established on the concept of primary and secondary sources and migration stories within Vermont, students were ready to create a product—the mini-comic—that illustrated their learning. Using primary sources on the 1918 Flu Epidemic from the Vermont Historical Society and Vermont Folklife interview excerpts on farming and foodways topics, the students began listening to audio transcripts of oral histories. They were encouraged to visualize and draw pictures as they listened, write down quotations, and summarize key points.

We were fortunate to have comic artist Marek Bennett for a three-day residency at our school. He worked with grades 4 and 5 and quickly engaged them on the basics of creating comics, from how to fold and cut a sheet of paper to create an eight-page comic book, to how to use his P.I.E. acronym (Pencil, Ink, Erase) to draft and revise based on feedback from other students. On his way out the school door on the final day of the workshop, one of the kindergarten teachers stopped Marek Bennett to thank him, explaining that some of her former students had come by her classroom to share their comics with her. They were so proud and excited to share their Vermont history comics with her.

Works Cited

Alvarez, Julia. 2009. Return to Sender. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

American Association of School Librarians. AASL Standards Framework for Learners. American Association of School Librarians, https://standards.aasl.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/AASL-Standards-Framework-for-Learners-pamphlet.pdf.

Anonymous Dairy Farmer (Interviewee). Interview Excerpt – Vermont Dairy Farmer: Louis could lasso a cow. Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/29.

Anonymous Dairy Farmer (Interviewee). Interview Excerpt – Vermont Dairy Farmer: The community…accepts them. Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/30.

Bennett, Marek, Julia Grand Doucet, Teresa Mares, and Andy Kolovos (eds). 2021. The Most Costly Journey: Stories of Migrant Farmworkers in Vermont Drawn by New England Cartoonists. English Language edition. Middlebury VT: Open Door Clinic.

—. 2021. El Viaje Más Caro : Historias De Trabajadores Migrantes De Agricultura En Vermont Dibujadas Por Artistas De New England. Spanish Language ed. Middlebury VT: Open Door Clinic.

Historical Society. 2023. Ben Robb and Maple Sugar Interview. SoundCloud audio, https://soundcloud.com/bratthistoricalsoc/bhs-e400-ben-robb-and-maple-sugar-interview.

Cruikshank, Julie. 2005. Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver, B.C: University of British Columbia Press.

Willcox, Ashley Consolo, Sherilee L. Harper, and Victoria L. Edge. 2013. Storytelling in a Digital Age: Digital Storytelling as an Emerging Narrative Method for Preserving and Promoting Indigenous Oral Wisdom. Qualitative Research.13.2:127–47, https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446105.

Winter Jonah and Nancy Carpenter. 2020. Mother Jones and Her Army of Mill Children. New York: Schwartz & Wade Books.

Farnham, Euclid (Interviewee) and Priscilla Farnham. Interview Excerpt – Euclid and Priscilla Farnham on changes to dairy farming practice, Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/18.

Galman, Sally Campbell. 2007. Shane, the Lone Ethnographer: A Beginner’s Guide to Ethnography. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

The Golden Cage. Vermont Folklife, Middlebury, VT, https://www.vtfolklife.org/exhibits-feed/the-golden-cage.

Knoll, Michael, Tina Menendez, and Vanessa Navarro Maza. 2020. Fostering Cultural Equity at HistoryMiami Museum. Journal of Folklore and Education. 7:88.

Kinsey-Lamb, Madaha. 2020. We Are All Essential: Is the Heart the Last Frontier? Journal of Folklore and Education. 7:9-18.

Kurosawa, Akira, dir. Rashomon. 1950. United States: RKO Radio Pictures.

McDonald, Bonny and Alexandria Hatchett. 2021. Stumbling into Folklore: Using Family Stories in Public Speaking.” Journal of Folklore and Education, 8:74-84.

Morales, Selina, ed. 2020. Teaching for Equity: The Role of Folklore in a Time of Crisis and Opportunity. Journal of Folklore and Education. 7.

Nowell, Shanedra. 2008. The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot and Its Legacy: Experiencing Place as Text. Yale National Initiative, https://teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_11.04.08_u.

Occupational Folklife Project. American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/occupational-folklife-project/about-this-collection.

Oral History Summer School (@oralhistory_summerschool). 2022. “What is oral history?” Instagram, September 2. https://www.instagram.com/p/CiBcN2kJi9G/?igshid=Y2I2MzMwZWM3ZA==

Paricio, Javier. 2021. Perspective as a Threshold Concept for Learning History. History Education Research Journal. 18.1:109–25, https://doi.org/10.14324/HERJ.18.1.07.

Ryan, Pam Muñoz. 2002. Esperanza Rising. New York: Scholastic.

Shopes, Linda. 2002. Making Sense of Oral History. History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/oral.

Smekens Education Solutions, Inc. 2018. Somebody…Wanted…But…So…Then. Smekens Education Solutions, Inc., https://www.smekenseducation.com/wp-content/uploads/archive/files/SWBST_new.pdf

Spellman, Carol. 2019. Introduction. Journal of Folklore and Education. 6:5-7.

Spradley, James P. 1979. The Ethnographic Interview. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Stanford History Education Group. Lunchroom Fight I. Stanford History Education Group, https://sheg.stanford.edu/history-lessons/lunchroom-fight-i.

Sunstein, Bonnie. ed. 2019. The Art of the Interview. Journal of Folklore and Education. 6:1-3.

URLs

Ben Robb and Maple Sugar Interview https://soundcloud.com/bratthistoricalsoc/bhs-e400-ben-robb-and-maple-sugar-interview

Oral History Sumer School https://www.oralhistorysummerschool.com/oral-history-summer-school

Listening in Place https://www.vtfolklife.org/topic-covid19-pandemic

Using Formal Interviews to Build Understanding in Social Studies https://jfepublications.org/article/using-formal-interviews-to-build-understanding-in-social-studies

Tell Me What the World Was Like When You Were Young: Talking About Ourselves https://jfepublications.org/article/tell-me-what-the-world-was-like-when-you-were-young

A NOTE: Bridging Cultural Gaps Through Interviews https://jfepublications.org/article/a-note

1918 Flu Epidemic, Vermont Historical Society https://vermonthistory.org/flu-epidemic-1918

Vermont Folklife interview excerpts on farming and foodways topics https://folksources.org/resources/collections/show/1

Transcript of 1988 interview with Euclid and Priscilla Farnham, Tunbridge, VT, conducted by Gregory L. Sharrow (link to audio excerpt

Transcript of 1988 interview with Euclid and Priscilla Farnham, Tunbridge, VT, conducted by Gregory L. Sharrow (link to audio excerpt