MKE Roots students visiting murals about Milwaukee Latinx history. Photo by Melissa Gibson.

“Is that 16th Street? Where it turns into César Chávez?” Rigo asked his teacher.1 She nodded, and he continued to inspect the projected photos. “That one—Crazy Jim’s—there’s still a car dealership there. My uncle used to work there.”

Another student chimed in. “You mean Velasquez Motors? The one at the corner? By the bridge? It’s not a car dealership anymore.”

Rigo shook his head. “No, no, not Velasquez. Further down, past the grocery store and the murals. There’s a used car dealership.” He gestured up at the black-and-white photo on the video screen. “It’s the same place where all the racists are standing up there in that picture.”

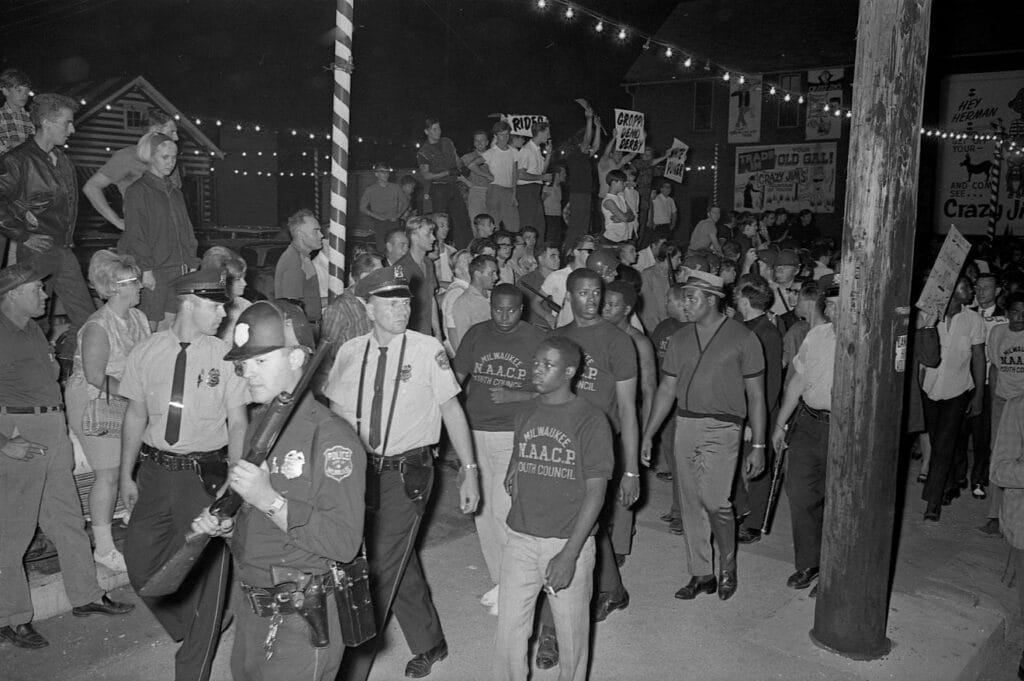

Rigo and his classmates at the Juvenile Justice Detention Center (JJDC) were looking at photos from Milwaukee’s Open Housing Marches—200 days of consecutive anti-segregation protests organized by youth activists in 1967 and 1968 (Jones 2009). This photo documented white counter-protestors who later assaulted young Black marchers on an early night of marching.

August 29, 1967; Milwaukee, WI; Protesters on Milwaukee’s south side taunt NAACP Youth Council marchers in this file photo. The youth council and its adviser, Father James E. Groppi, held marches from the north side to the south side on Aug. 28 and Aug. 29, 1967. Both demonstrations were met by thousands of protesters. © Milwaukee Journal Sentinel via Imagn Images

Like all youth at JJDC, Rigo and his classmates attend school while incarcerated. Most days, they are reluctant students. As his teacher, Ms. Savannah, explained, many struggle to see a future for themselves, and school rarely fits into whatever vision they can muster. Roughly half the youth at JJDC qualify for special educational services, and many leave JJDC without a high school diploma or GED.

But on this day, Rigo and his classmates were engaged. The students had intimate knowledge of the places documented in these sources. This lesson was about their city, their neighborhoods, their streets, and they knew well the conditions that their peers across time and space were protesting. They, too, knew that their city still suffered from the harms of segregation, discrimination, and economic and educational disinvestment. Their experiential, community-based knowledge connected to their learning.

Rigo, his classmates, and his teachers are participants in MKE Roots: The Democratizing Local History Project, a U.S. Department of Education-funded educational outreach project of Marquette University’s Center for Urban Research, Teaching and Outreach.2 In the 2024-25 school year, MKE Roots partnerships reached over 1,500 students in 33 classrooms at 23 schools in Milwaukee County, including JJDC. MKE Roots offers a pedagogical ecosystem for teaching a critical, place-based history of Milwaukee’s communities—with particular attention to historically and contemporarily marginalized communities (e.g., BIPOC, LGBTQ+, dis/ability). Three central principles guide this work: 1) the importance of centering youth in storytelling; 2) the power in place-based learning; and 3) the belief that transforming narratives transforms communities. Through the documentation and sharing of community history and cultural wealth, MKE Roots aims to shape how Milwaukee’s young people see themselves within the civic landscape of our city: as change agents, community contributors, and citizens who matter.

What MKE Roots has demonstrated is that documenting and centering community stories and folklife in the teaching of history and civics can be transformative for students in terms of how they see themselves, their communities, and their futures (Cuevas 2016; Kinloch, Penn, and Burkhard 2020; Maines, Pierce, and Maslett 2011; Miles 2019). The connections Rigo was making were a step toward realizing that his knowledge matters and that it is people just like him who push our city toward justice. Below, we elaborate on the MKE Roots approach, which is rooted in the MKE Roots Ecosystem—a digital space of transformative, multimodal documentation of community stories. We situate anonymized, composite vignettes (Bradbury-Jones, Taylor, and Herber 2014) from our ongoing case study research (Stake 1995) in partner classrooms to reveal the transformative potential of folklife activated for cultural and community education.

Documenting Community Stories in Social Studies: The MKE Roots Approach

MKE Roots arose in response to expressed community needs. Specific catalysts included the 50th anniversary of Milwaukee’s Open Housing Marches in 2017-18, when educators sought guidance on teaching this local story; the Covid-19 school shutdowns, when schools sought help developing credit recovery programming; and the perceived rise in youth crime after the pandemic.

Critical, place-based learning offers a school-based way to meet these needs. In place-based learning (Sobel 2004), the physical community is an extension of the classroom and the site for students’ authentic inquiries across disciplines. In critical place-based learning, the physical and social community nurtures students’ critical consciousness (Freire 2000), helping them learn to read the word and the world and inquire about power, justice, and social change. Place is essential: The authentic spaces in which students-as-community-members exist are rich with narratives, stories, knowledges, cultures, and skills that can be reflected back to students through culturally sustaining practices (Paris and Alim 2017).

MKE Roots prioritizes physical communities as important sites of learning, whether youth move into the world or the world is invited into the classroom, and it is grounded in the folklorist’s understanding that “the world we live in is a living museum” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1983, 10), especially concerning the values, relationships, and knowledge that convey “notions about the proper ways to be human at a particular time and place” (Hufford 1991, 6). In Milwaukee’s marginalized communities, a common thread of that folklife is the enduring commitment to and role of everyday people in social change. However, for Milwaukee students—who are 84 percent low-income and 90 percent BIPOC (MPS 2025)—this community cultural wealth (Yosso 2005) is not often embraced in school (Rodrigues 2022).

The MKE Roots Ecosystem

The stories within our city’s communities are a powerful opportunity to re-engage with and re-invest in youth and thus are the heart of MKE Roots. In addition to offering professional development, classroom partnerships, and curriculum materials, MKE Roots hosts a freely available Digital Ecosystem that serves as a kind of community and educational archive documenting often overlooked stories of cultural, civic, and community life. Initially, this digital work was conceived solely as conventional curriculum (e.g., lesson and unit plans), but through work in classrooms and with teachers, it became clear that what educators and youth most wanted was a centralized repository for community stories that they could explore independently. The MKE Roots Ecosystem thus grew into a multimodal space of transformative documentation. Unlike existing educational approaches in which local history is only relevant when it connects to larger curricular topics, the MKE Roots Ecosystem allows the stories of communities to stand on their own and to become the interwoven fabric of the story of Milwaukee. While viewers are invited to engage with Milwaukee stories thematically, most engage with the Ecosystem as a storytelling web that documents the histories of and connections between communities.

Screenshot of the freely available Digital Ecosystem that serves as a community and educational archive.

In the Ecosystem, places around Milwaukee—from recognized monuments to artists’ collectives to neighborhood pubs—are “pinned” with narratives, archival documents, original research, and instructional suggestions, and teachers and students are invited to contribute content to bring these pins to life. Ecosystem pins are designed to be used in the classroom as multimodal texts or in the world as experiential guides. Pins are written to invite students to shed deficit narratives and instead understand that their communities are “deep lodes of worldview, knowledge, and wisdom, navigational aids in an ever-fluctuating social world” (Hufford 1991, 6). As shown in the following vignettes, teachers use these pins as content for lessons, guides for field experiences or as sources for student-driven inquiry.

MKE Roots Ecosystem Pin Screenshot.

MKE Roots in Action: Composite Classroom Vignettes

What might happen when young people’s learning is rooted in stories of the social action, cultural vibrance, and historic longevity of their own communities? How might rooting curriculum in students’ place in the world also root students themselves? If students experience a contextually and culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings 1995) learning experience, how might their sense of themselves as community members be transformed? The situated vignettes below show how students engage with the community stories documented in the MKE Roots Ecosystem, and how that engagement—shaped by the MKE Roots guiding principles—moves toward transformation by: 1) centering youth in storytelling, thus allowing the quotidian dimensions of community life to become as important as “official” narratives; 2) harnessing the power of place-based learning, which invites students to seek and share community stories; and 3) acknowledging the transformational power of narratives, thus honoring multimodal storytelling as a valuable form of knowledge production.

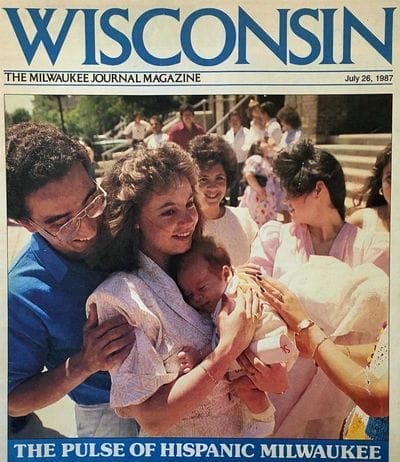

July 26, 1987; Milwaukee, WI, USA; Full front page color scan of Wisconsin, the Milwaukee Journal Magazine. Headline: The Pulse of Hispanic Milwaukee.

© Milwaukee Journal Sentinel via Imagn Images.

Centering Youth in Storytelling: The Quotidian Matters

In the opening vignette, Rigo was engaged in an important dimension of youth storytelling: honoring his quotidian experiences and knowledge. This is, in many ways, the foundation of transformative storytelling: acknowledging the significance of our daily lives and their spaces, neighborhoods, and people. For example, MKE Roots historian Sergio González regularly models this when sharing a story about finding in local archives a photo of himself as a baby surrounded by his parents, family members, and parishioners at his christening on the steps of Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish. He is the archive. His story demonstrates how official records grow from documenting the regular lived experiences of communities (González 2024). In fact, honoring the quotidian lives of community members—especially those from marginalized communities that have been ignored in official institutional archives—is at the heart of community archival work. Community archives can be seen as an act of protest against the power inequities in knowledge production and archival retrieval, striving instead to “uncover & provide a platform for previously marginalized voices” in our collective memory (Caswell 2014, 32). This is the approach to community storytelling that MKE Roots emulates in its digital ecosystem.

When students see this attention to the quotidian modeled, they begin to see how their own daily experiences and stories are essential to understanding our city.

At South Side Middle School, students were curious about the personal connections they shared with civil rights activists. They viewed a 1968 protest image from the Eagles Club, an all-white social club now known as The Rave. Students were in disbelief: This place where they begged to see their favorite hip hop stars was once a racist men’s club?! One student was particularly flabbergasted: “I swear my mom used to go swimming there when she was a kid. But my mom is Black….I don’t understand how she could have?” Her teacher, Mrs. Green, encouraged her to learn her mom’s story and bring it back to class. Other students connected to the activist Father James Groppi. “Groppi like…Ms. Groppi? Who teaches down the hall?” “Or like the grocery store down by the lake?” Mrs. Green confirmed these connections: Ms. Groppi was Father Groppi’s daughter, and the grocery store was owned by his extended family. This celebrated historic figure became, simply, a member of students’ communities, his activism woven into the regular fabric of their lives.

Students also begin to seek out these quotidian experiences and stories when out in the community.

Students from St. Gertrude High School’s credit recovery program visited the Sherman Phoenix, a community marketplace developed after the 2016 Sherman Park Uprising, which protested the police shooting of Sylville Smith. They talked with the makers and artists based there and learned how these artists saw their art as part of social change in Milwaukee and how their involvement with the Sherman Park Uprising helped them embrace their art as essential to community justice. Other students visited Zócalo Food Truck Park in the Walker’s Point neighborhood, a historically Latinx community experiencing rapid development. They met with the park’s founder and head chef and learned how traditional foodways can disrupt gentrification in favor of community self-development.

By honoring the quotidian through storytelling, students learn that their daily lives are the material way that both history and social change happen. Where we eat, where we recreate, where we shop—and who we do it with—are the woven fabric of our communities’ folklife. That folklife makes up the stories, the history, and the future of our city.

Power in Place: An Invitation to Share Stories

The MKE Roots Ecosystem shares digital and multimodal stories of specific Milwaukee places. Pins connect to oral histories, photo archives, local newspapers, and community-run social media accounts, expanding notions of what counts as curricular and archival material. While many of the pins are in students’ own communities, the stories shared about those places are often unknown to students. The Ecosystem thus becomes an invitation to educators and students to share community stories: How should we tell the story of our Milwaukee?

Ms. Brittany’s Black Student Union (BSU) at Central City High School exemplifies how students take up this invitation to share stories.

BSU students were studying Black labor rights, of interest to them after the 2024 presidential election when community members worried about the economy and jobs. Students sought to understand what, exactly, this worry meant, and they explored pins in the Ecosystem that highlighted stories of local labor activism—places like A.O. Smith, Rockwell Automation, and Allen Bradley, where Black workers and organizers led powerful protests against segregation, deindustrialization, and economic disinvestment. Ms. Brittany chimed in during their inquiry: “My parents worked at A.O. Smith right up until it closed. That was a devastating moment in our neighborhood.” When we prodded her to share more of this story with students, she hesitated: “I didn’t really think that was official enough history to teach them.” But it was exactly the kind of history students wanted to hear. Ms. Brittany eventually discussed the A.O. pickets and Allen-Bradley protests that her family members participated in and how the way of life in her neighborhood was altered by the shuttering of factories. Later, when Mr. James, an educational paraprofessional, visited their class and heard their conversation, he also chimed in, revealing how he had participated in many protests over the years.

The documented stories in the Ecosystem became an invitation to share stories otherwise unknown to students.

Similarly, when visiting murals around the city depicting Milwaukee’s Latinx community using Ecosystem pins as their itinerary, students in St. Gertrude’s credit recovery program were surprised to see depictions of braceros and migrant farmworkers and to see them represented as important to Wisconsin (Salas 2023).

At the United Community Center’s mural, Nayeli shared that her grandfather had been a bracero and that was how her family had moved to the U.S. from Mexico. No teacher had ever mentioned the bracero program before. Nayeli said she didn’t know this was something she could talk about at school. Another student, Paloma, shared a similar story when looking at the Third Ward mural honoring Obreros Unidos. As the teacher talked about the workers’ march across the state in 1966, Paloma raised her hand. “My grandpa was there. He marched from Wautoma to Madison. I don’t think he knows about this mural.” When she learned that César Chávez visited Wisconsin to meet the marchers, she exclaimed: “Maybe my grandpa met him!”

In these moments, we see students encountering place-based community stories, connecting them to their daily lives, and honoring community knowledge in the schooling context. These place-based stories further inspire students to move beyond what is officially catalogued and to invite community members to share their stories.

Transformative Narratives: Storytelling as Knowledge Production

A final important shift happens when students begin to see the seeking, documenting, and sharing of community stories as authentic knowledge production. By documenting previously undocumented narratives, students contribute to the transformational potential of multimodal storytelling.

Oral history has become a primary tool for students to document community stories in deeply personal ways.

At suburban Bishop High School, Michelle noted that the Open Housing marchers walked through Marquette University when her grandpa was a student there; she wondered if her grandfather remembered them. For a final project, Michelle chose to record an oral history interview with her grandfather. She was surprised to learn that he joined the marches with his Jesuit classmates. Michelle aimed to submit the interview to the StoryCorps archive in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. Matthew, a classmate of Michelle’s, was inspired to interview his grandparents when he realized his family sat at the intersection of the different waves of Milwaukee’s migration they’d learned about: One great-grandfather came here as part of the Pfister Vogel Tannery’s importation of workers from Mexico in the early 1900s. Another moved from the South during the Great Migration. One grandmother migrated from Puerto Rico after WWII, and the other was from a long line of German and Polish immigrants. Matthew knew each of these discrete stories, but it wasn’t until exploring Milwaukee history, specifically, that he understood the significance, declaring, “My family IS Milwaukee history.”

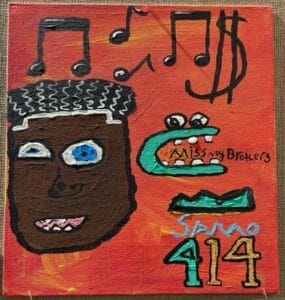

Teachers and students also rely heavily on visual art to support community storytelling. Through a partnership between MKE Roots and America’s Black Holocaust Museum—a Milwaukee museum, founded by lynching survivor James Cameron, that shares the history of slavery and Jim Crow and promotes remembrance, resistance, redemption, and reconciliation—youth are invited to display their art in regular student exhibits. ABHM is a public museum that hosts opening night events for these student exhibits. For example, students from JJDC have exhibited their art in the style of both local and international artists such as Mauricio Ramirez and Jean-Michel Basquiat to tell stories important to their lives as Milwaukeeans, for example, memorials for friends, community violence, music they love, or entrepreneurship ideas, and to represent themselves as community members. Students from St. Gertrude’s credit recovery program end their yearlong exploration of Milwaukee’s community history by assembling a photo essay exhibit that tells the story of important places in their Milwaukee lives. One student designed a visual monument for the 6th Street Bridge, the site of important immigration marches that she attended with her family as a child. In this way, students’ visual storytelling moves from personal classroom work to a more ”official” documentation of narratives about Milwaukee.

- Sample of student art.

- Photo essay from St. Gertrude’s program exhibit at ABHM.

The Transformative Potential of Community Storytelling in the Classroom

Initial 2024-25 survey data on the first formal cohort of MKE Roots classrooms demonstrates the transformative potential of community storytelling in the classroom. After only one academic quarter of instruction, students in the classrooms of MKE Roots teachers demonstrated a 50 percent positive change in their beliefs about their community and a 10 percent positive change in their beliefs about themselves as community members and civic actors. These numbers suggest that a critical, place-based approach can re-engage young people as community citizens.

Even more powerfully, our case study data reveal that community storytelling is transforming how participating students understand themselves, their futures, and their experiences of the world. For many students, interacting with the community stories documented in the MKE Roots Ecosystem is a turning point, a moment when they finally see themselves and their experience of the world reflected back to them in the school curriculum.

When Jamila, a Black student in St. Gertrude’s credit recovery program, first saw the photo Rigo viewed in the opening vignette, she was flummoxed. “But my history teacher last year said that racism was only a problem in the South back then.” Her current teacher pointed up at the image and flipped through a few others from Milwaukee that featured Klansmen and Nazi signage and asked, “Well, what do you see in the photos?” Jamila sat silent for a moment, then said: “I mean, I think this city is racist. Maybe it always has been?”

Ku (sic) Klux Klan in front of Eagles club. © Milwaukee Public Library. Used with permission.

The photos seemed to help Jamila recognize the authority she had to question official school narratives based on her own interpretations of evidence and her own lived experience.

For the youth at JJDC, engaging with stories of youth resistance and activism specifically seemed to invite a reconsideration of who they were and could be in their Milwaukee communities, an important component of freedom dreaming with incarcerated youth (Meiners 2011).

A class at JJDC was learning about the NAACP Youth Council Commandos who protected the Open Housing marchers (WUWM 2017). Their teacher, Ms. Nina, knew one Commando, Prentice McKinney, personally, and she shared a story she had heard about how he came to the movement. As a teenager, McKinney was gang-affiliated, and when Father Groppi began working with young people, McKinney was afraid that the priest was organizing a rival gang. He went to talk with Groppi, learned Groppi was working with youth activists, and ended up recruiting friends to join the movement. Ace, one of the youngest students in the class, shouted out, “Wait a minute! You’re telling me he was a gang member?” Ms. Nina nodded. “And he became, like, him? That guy could’ve had a record?!”

Ace seemed to feel connected to McKinney’s story, which seemed to suggest to him that being system-impacted didn’t preclude someone from doing good in the community or participating in abolitionist future-building (Meiners 2011).

When class ended, Ace came up to the MKE Roots researchers and said, “I really want to go to college but…no way a college will let me in with a record. Right?” In fact, the researchers told him, there are scholarships available specifically for system-impacted students in Milwaukee County. Ace bounced on his toes: “For real? Then I’m going to college. I swear.”

Maybe the two moments in Ace’s class were not connected, but in light of initial survey data, when we think about Ace and Jamila and Rigo—and everyone else in a MKE Roots partner classroom—we can’t help but see these moments as transformation happening in real time.

By interacting with, inquiring about, and documenting community stories in classroom spaces, students are undergoing a shift in their community cultural identities—how they understand themselves, their futures, and their communities. This is a shift that has potentially life-changing material consequences, perhaps captured best by Devin, another JJDC student who, after the lesson on the Commandos, mused, “I wish I’d learned this stuff sooner.” Gesturing at the locked rooms, JJDC-emblazoned uniforms, and armed security guards, he shook his head. “It’s probably too late for me now, but if I’d known about all this before…” He shrugged. “Maybe I wouldn’t be here.” Devin seemed to understand viscerally how differently he might have experienced life in Milwaukee if he had these stories of resistance, organizing, and community to buffer him.

Melissa Gibson is an Associate Professor of Education at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where she is also the Faculty Director of MKE Roots: The Democratizing Local History Project in Marquette’s Center for Urban Research, Teaching, and Outreach. Her research broadly focuses on enacting educational justice in diverse classrooms. She began her career as a middle and high school teacher of Social Studies and English Language Arts in both the U.S. and Mexico. She has a PhD in Curriculum Instruction from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

derria byrd is an Assistant Professor of Education at Marquette University and Qualitative Research Methodologist for MKE Roots in Marquette’s Center for Urban Research, Teaching, and Outreach. As a critical scholar of higher education, she draws on sociology of education, organizational studies, and critical theory to examine the institutional forces that hinder and facilitate progress toward equity for marginalized social groups. Her current research centers the lived experiences of first-generation academics—that is, former first-generation college students who now have careers in the academy. She has a PhD in Educational Policy Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Marquette University Center for Urban Research, Teaching, and Outreach (CURTO).

Endnotes

- All names are pseudonyms, per institutional IRB-approved research protocol.

- 2023-25 U.S. Department of Education History & Civics National Activities Awardee

Works Cited

Bradbury-Jones, Caroline, Julie Taylor, and Oliver Herber. 2014. Vignette Development and Administration: A Framework for Protecting Research Participants. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 17.4:427–40. DOI:10.1080/13645579.2012.750833

Caswell, Michelle. 2014. Seeing Yourself in History: Community Archives and the Fight Against Symbolic Annihilation. The Public Historian. 36.4:26-37. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/tph.2014.36.4.26.

Cuevas, Pedro Antonio. 2016. The Journey from De-Culturalization to Community Cultural Wealth: The Power of a Counter Storytelling Curriculum and How Educational Leaders Can Transform Schools. Association of Mexican American Educators Journal. 10.3:47-67.

Freire, Paulo. 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th anniversary ed. New York: Continuum.

González, Sergio. 2024. Strangers No Longer: Latino Belonging and Faith in Twentieth-Century Wisconsin. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Hufford, Mary. 1991. American Folklife: A Commonwealth of Cultures. Washington, DC: Library of Congress American Folklife Center, https://locallearningnetwork.org/resource/american-folklife-a-commonwealth-of-cultures.

Jones, Patrick. 2009. The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kinloch, Valerie, Carlotta Penn, and Tanja Burkhard. 2020. Black Lives Matter: Storying, Identities, and Counternarratives. Journal of Literacy Research. 52.4:382-405.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1983. An Accessible Aesthetic: The Role of Folk Arts and the Folk Artist in the Curriculum. New York Folklore: The Journal of the New York Folklore Society. 9.3/4:9-18. https://locallearningnetwork.org/resource/an-accessible-aesthetic.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1995. Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal. 32.3:465-91.

Maines, Mary Jo, Jennifer Pierce, and Barbara Laslett. 2011. Telling Stories: The Use of Personal Narratives in the Social Sciences and History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Meiners, Erica. 2011. Ending the School-to-Prison Pipeline/Building Abolition Futures. The Urban Review. 43: 547–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-011-0187-9

Miles, James. 2019. Historical Silences and the Enduring Power of Counter Storytelling. Curriculum Inquiry. 49.3:253-59.

Milwaukee Public Schools. 2025. Organizational Profile, https://mps.milwaukee.k12.wi.us/en/District/Initiatives/Strategic-Plan/Organizational-Profile.htm.

Paris, Django and H. Samy Alim. 2017. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. New York: Teachers College Press.

Rodrigues, Marc. 2022. Justice Delayed Is Justice Denied: Milwaukee Public Schools, Persistent Disparities, and the School-to-Prison-and-Deportation Pipeline. Milwaukee: Leaders Igniting Transformation and the Center for Popular Democracy..

Salas, Jesus. 2023. Obreros Unidos: The Roots and Legacy of the Farmworkers Movement. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Sobel, David. 2004. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities. Great Barrington, MA: Orion Society.

Stake, Robert. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

WUWM. 2017. NAACP Commando Prentice McKinney Looks Back at Milwaukee’s Open Housing Marches, 50 Years Later. Lake Effect Spotlight, August 28, https://www.wuwm.com/podcast/spotlight/2017-08-28/naacp-commando-prentice-mckinney-looks-back-at-milwaukees-open-housing-marches-50-years-later.

Yosso, Tara. 2005. Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth. Race, Ethnicity, & Education. 8.1:69-91.

URLs

MKE Roots https://mkeroots.raynordslab.org

Historical Images from Milwaukee’s Open Housing Marches, https://www.jsonline.com/gcdn/authoring/authoring-images/2024/03/01/PMJS/72798459007-aug-1929-1966-mjs-milwaukee-housing-race-historical-archive.JPG?width=1320&height=878&fit=crop&format=pjpg&auto=webp

Digital Ecosystem https://mkeroots.raynordslab.org/index.php/ecosystem

Pulse of Hispanic Milwaukee https://cushwa.nd.edu/assets/246003/400x/milwaukeejrnl_072687.jpg

Sherman Phoenix https://www.shermanphoenix.com/about-us

ABHM–America’s Black Holocaust Museum https://www.abhmuseum.org

StoryCorps Archive https://storycorps.org/discover/archive