Alvin C. Krupnick Co, photographer. Smoldering ruins of African American’s homes following race massacre in Tulsa, Okla., In Oklahoma Tulsa, 1921. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/95517072.

With candidates screaming at political opponents on the television and state legislatures across the country introducing or passing laws on how teachers speak about race and racism (Schwartz 2021), students in K–12 Social Studies classrooms need effective models of civic discourse and tough conversations even more than before. As Social Studies teachers with decades of combined experience and as teacher educators at a predominantly white midwestern university, we center our curriculum around teaching challenging and whole histories, analyzing primary sources, and creating classroom community spaces where difficult dialogues can safely happen.

In our current political and cultural climate, this approach may seem like a pie in the sky ideal, but in our Social Studies education methods courses, we use folk sources, such as oral histories from survivors, primary source photographs and news clippings of historic events, and current young adult literature, including Dreamland Burning (Latham 2017) and Black Birds in the Sky (Colbert 2021). Leveraging these resources related to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, we model how to facilitate difficult dialogues or tough conversations around history, race, class, and culture in the classroom. While we primarily work with preservice and early career teachers in our 16-week Social Studies in the Elementary Curriculum and Teaching and Learning Social Studies in the Secondary School Methods courses, we feel all Social Studies educators should use strategies that get students to think deeply about historical events and their effect on our present-day social issues. Teaching with primary sources allows students to explore multiple perspectives or points of view to “relate in a personal way to events of the past,” and develop “a deeper understanding of history” (Library of Congress n.d.). With growing political polarization and partisanship, we see people struggle to see each other’s point of view and often lack a willingness to engage in difficult conversation in a professional manner. Primary sources “serve as points of entry into challenging subjects,” as Potter shares (2011, 284). They can “get a conversation started” (2011, 284) and help students discover “little known facts and different perspectives” (2011, 285) along the way. In this article, we hope to offer educators specific teaching strategies and learning activities aimed at fostering difficult dialogues around primary sources.

Teaching the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Most of the preservice teachers we train never learned about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and similar events connected to the Red Summer of 1919 before entering college. Even students growing up in and around Tulsa share this knowledge gap. Most of our students identify as white and come from urban, upper-middle-class upbringings or grew up in lower- and middle-class rural communities—both often racially homogenous communities where they have faced very little discrimination or adversity in their lives based on race or culture. It is difficult for our college-age preservice teachers to understand the struggles that the residents of Greenwood (a neighborhood of Tulsa) faced or the severity of racism before, during, and after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

When teaching the history related to the Tulsa Race Massacre, we encourage students to start with Greenwood’s prosperity and its nickname “Black Wall Street,” a nickname purportedly assigned by Booker T. Washington (Crowe and Lewis 2021). Ottawa “O.W.” Gurley and his wife Emma purchased the land that established the Greenwood District in 1906, a year before Oklahoma gained statehood (Gara 2020, Thomas 2021). They dedicated the land to be sold in parcels to African Americans only, laying the groundwork for what would become the most prosperous Black community in the United States. Before the destruction caused by the Tulsa Race Massacre, Greenwood boasted 10,000 residents and 35 square blocks of homes, businesses, churches, hospitals, libraries, and so much more (Johnson n.d.). This thriving, vibrant Black community was targeted by white Tulsans in what historians call “the single worst incident of racial violence in American history” (Ellsworth n.d.).

The Tulsa Race Massacre took place May 31 to June 1, 1921. Many pinpoint the elevator incident as the catalyst for the Tulsa Race Massacre, when Dick Rowland, a young Black man, was accused of assaulting a young white woman, Sarah Page. But through the Learning Through Listening: Rumor Conspiracy Studying the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre lesson, local folklore presents multiple stories as possible motives for the violence. In our methods courses, students investigate the experiences of Greenwood residents during and after the Tulsa Race Massacre through primary sources, including the hundreds of photographs taken during the event. Through the work of oral history researchers to capture the memories of survivors decades after the event, we also have access to video and audio testimony of what happened in 1921. As Social Studies teacher educators, we let the primary sources do much of the teaching and allow our preservice teachers’ questions to drive the learning and set the stage for difficult dialogues around this challenging history.

Starting the Conversation

Just as literacy instructors use touchstone texts, or revisit books repeatedly to model effective literacy techniques, we use the Tulsa Race Massacre as a touchstone event in the methods course, revisiting the topic throughout the semester (Johnson 2009). For example, Robin Fisher’s former fourth-grade students loved the book Henry’s Freedom Box: A True Story from the Underground Railroad, and immediately became attached to Henry, his suffering, and his will to survive as an enslaved person (Levine and Nelson 2007). Using this as a touchstone text meant referring to this book throughout the school year and connecting back to Henry as we covered other topics, such as discussing creative introductions and the way the authors intentionally used their words to elicit emotion and hook the reader into the story. As a touchstone event, teaching about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and preparing our preservice teacher candidates to handle difficult dialogues around racially charged historical events in their future classrooms are pillars of our Social Studies methods courses. When we poll students at the beginning of the semester, uncomfortable conversations are something students are most concerned about. Many do not know how to approach teaching the Tulsa Race Massacre, while others are terrified of backlash from parents. The introduction of anti-Critical Race Theory (CRT) legislation across the country includes Oklahoma House Bill 1775 (OK HB1775) that bans “teaching about white supremacy, patriarchy, implicit bias, unconscious bias, structural racism, and even empathy towards oppressed groups” (Bronstein et al. 2023, 34). Since the passage of this law in 2021, many educators question if it is even appropriate to teach the complex and racially charged history surrounding the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Those willing to do so struggle to select instructional strategies that “embrace multiple perspectives, narratives, and interpretations of a shared U.S. history” that align with Social Studies education demands (Bronstein et al. 2023, 33). Preparing future educators to teach in this hostile climate endows us with an even stronger responsibility to help our teacher candidates navigate difficult dialogues and challenging topics.

Before digging into history of the Tulsa Race Massacre we begin with two short writing prompts in which we ask students to check for their blind spots by evaluating their inner circle to understand where their personal beliefs come from and by identifying other perspectives around a challenging topic. We discovered that many of our college-aged teacher candidates had really never thought about how their opinions and views were influenced by those close to them. We want students to look at their own inner circles to see how their thoughts, impressions, and beliefs are influenced by those they value most. This activity, loosely based on an Inclusion Works protocol, asks students to do three things:

- List the five people closest to them. These are the people they turn to when things go wrong or they need to make a decision.

- Next students are instructed to place a checkmark next to the person’s name when they have something in common with them. We ask such things as age, gender identity, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and religion.

- Students are then given time to reflect privately and ask themselves a series of questions:

- Did you realize your close circle was so like or different than you?

- How does this knowledge influence your thinking?

- Why do you think it is important to recognize this as a teacher?

- How might someone with a very different circle of people see things from a completely different perspective?

- How does perspective influence relationships and dialogues among people?

(Hive Learning n.d.)

Through our experiences with preservice teachers, we found that allowing students to be introspective before tackling such a racially charged historical event led them to be more open-minded and to interrogate their personal biases. By gently exposing these introspections at the start of the conversation, we are able to move forward and navigate the hard history.

While the inner circle activity is great to expose possible biases, it could make people self-conscious. In the second short writing activity, taken from a Facing History lesson titled Preparing Students for Difficult Conversations, our future teachers first write a private journal entry about what feelings they think people in the room might be having. Next they respond to a very short writing prompt: “I mostly feel ________ when discussing [the Tulsa Race Massacre], because ___________” (Facing History 2016). None of the students’ “I feel” statements are shared publicly. Next, students are asked to brainstorm what feelings they think others might be feeling in the room. Typically, students share common words or feelings in response to the Tulsa Massacre such as sad, confused, angry, horrified, nervous, and uncomfortable. To wrap up the activity, we open up the classroom to a short discussion about what the words shared have in common, where these feelings might have come from, and which words or opinions might be the most valid. Guess what? All feelings are valid. This strategy has been powerful for students in our Social Studies teaching methods courses to see that others feel the same way about this topic.

As we complete the post-writing reflection discussion, our teacher candidates comment that they appreciate the pressure being taken off them by asking what others might be feeling. There is a general consensus that they might not participate in the difficult dialogue had they been put on the spot with their own feelings. In many instances, this activity exposes feelings of white guilt with our preservice teachers expressing anger and shame over the events of the past, remorse over the lives lost, curiosity if their families were involved in the atrocities, and fear of repercussions even 100 years later. We reiterate that all these feelings are valid and lead to fruitful conversations about the influence of race, racism, socioeconomics, and history on our lives today. As with most activities in a teaching methods course, we discuss how this strategy might be helpful in their PK–12 classrooms. With the restrictions surrounding OK HB1775 and similar anti-CRT laws, we do caution teacher candidates about using these activities in the classroom. Despite the heightened political climate, each school culture is different, and this material has proven to be effective and appropriate for curricular standards. Our preservice teachers agree this would be a gentle way to lead into difficult content and conversations.

Centering Primary Sources

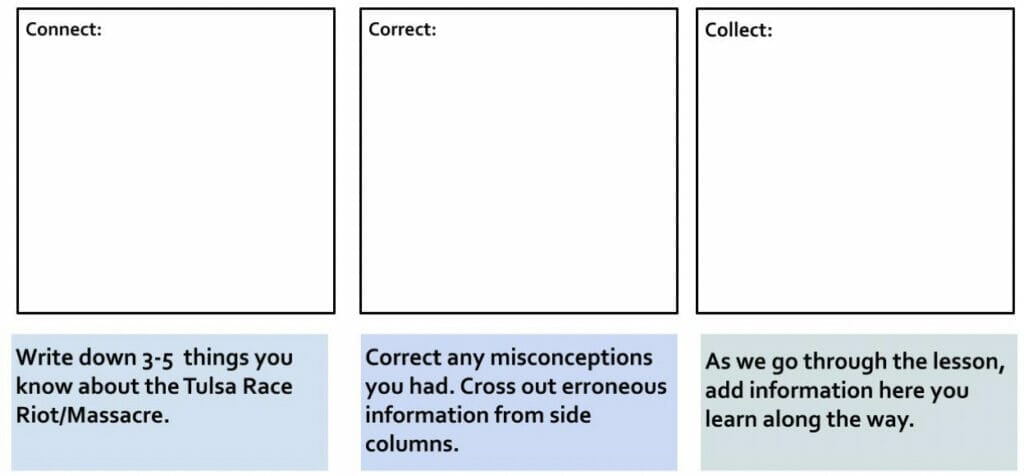

As we dive into the history surrounding the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre throughout the semester, we use several activities that interact, analyze, and respond to primary sources. Often at the beginning of our study, we use a “Connect, Correct, Collect” graphic organizer to activate students’ prior knowledge about the Tulsa Massacre (Neuhaus Education Center 2023). This chart is a variation of a KWL, which asks students what they already Know, Want to Know, and, after the lesson, what they Learned. Through “Connect, Correct, Collect” students connect their prior knowledge about the Tulsa Race Massacre to their knowledge of history past and present (Figure 1). While students learn new information in their daily lessons or throughout the semester, they add information to the Collect category. If students find information that contradicts what they thought they knew (or misconceptions), they cross out the misinformation from the Connect or Collect columns and place accurate information in the Correct column. The strength of this graphic organizer lies in the Correct column as it asks students to physically cross out misinformation or misconceptions and helps to solidify the correct information in their minds. Often this leads to great conversations about the importance of reliable sources, and preservice teachers quickly realize the most accurate information comes from primary source documents because corrections often need to be made when relying too much on secondary sources. After completing this activity, we ask students to reflect on their PK–12 Social Studies education, the teaching strategies and activities used, and if they were taught whole histories through this kind of inquiry and primary source analysis. Many come to realize how little they know about U.S. or World History and begin to research historical events independently to see if they truly know what happened in Tulsa in 1921 and beyond. These future teachers translate the principles of this learning activity as they design lessons of their own, often replacing textbooks with oral histories, newspaper articles, and primary source photographs accessed through cultural or historical societies, museums, and archives.

Figure 1. Connect, Collect, Correct graphic organizer activity allows students to list what they already know about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, add additional information as they continue to learn more throughout the lesson, and correct any misconceptions they may have about the event. Adapted from Neuhaus Education Center 2023.

We also center primary sources by exploring the experiences of the victims of the Tulsa Massacre. Oral histories recorded decades after the event give teachers and students a glimpse into what happened over 100 years ago. These oral histories are available through Voices of Oklahoma, the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, and the Tulsa Historical Society, as well as our folksources.org website and connected lesson plans. Another learning activity we frequently use with preservice teacher candidates, adapted from Rethinking Schools (Christensen 2012), asks participants to put themselves into the role of a Tulsa Race Massacre survivor and share what they saw or experienced in a Dinner Party or Mixer role-play activity. The curated roles contain first-person narratives from real people who witnessed the event. The narratives are based on primary sources and secondary sources taken from books by Tulsa Race Massacre historians. In small groups, teacher candidates mingle and share the stories and perspectives of Greenwood residents and what happened during the Tulsa Race Massacre. The conversations fostered when debriefing the role-play activity reveal lesser-known stories of the Massacre and help students understand the motivations, conflicts, and consequences of this event on the community. Most importantly, students ask hard questions, such as “Who bears the blame for the destruction of Greenwood?” and “Why did law enforcement deputize a mob?” We often pair the debrief activity with primary source photographs and maps to give students a more complete understanding of what happened in 1921. The Library of Congress analysis tools that ask students to observe, reflect, and question work well with the primary source photographs of the Tulsa Race Massacre available from folksources.org, the Oklahoma Historical Society, and Oklahoma State University.

Challenging Questions Lead to Difficult Dialogues

Throughout the Social Studies methods courses, our preservice and early career teachers learn hard history and how to teach it through these strategies, but the most important teaching strategy we model is inquiry—to let questions drive Social Studies learning. Often students will come up with their own questions, but it is also important that the instructor be prepared with questions to jumpstart meaningful conversations. As students gain more knowledge about the 1921 Race Massacre, the history of Greenwood, and the effects of this historical event on the community, city, state, and nation, we use discussion prompts, such as the questions listed below, to delve deeper and push their understanding beyond the simple questions of who, what, where, and when and toward the more complex questions of why and how. We have used these questions in our Social Studies methods courses to foster deeper understanding and difficult dialogues about the Tulsa Race Massacre:

- Should we call this event a riot or massacre?

- What motivated the perpetrators to attack the thriving Greenwood district?

- What role did the press play in the events of the Tulsa Race Massacre? Does the press bear any responsibility?

- What responsibility does the city/state have to revitalize Greenwood and North Tulsa?

- What are the lasting effects (economic, political, social) of this event on Tulsa? Oklahoma? The United States?

- What is the difference between “not racist” and “anti-racist”?

- How is being a “colorblind” teacher hurtful to students of color?

- What recent events in Oklahoma and the nation can we teach in connection with the 1921 Race Massacre? How are these connections relevant to students’ lives?

As students learn more about Greenwood and the Tulsa Race Massacre, the more questions they ask about why this history continues to be hidden. When PK–12 students and university teacher candidates start to ask challenging questions and seek out historical connections between people, places, and events across time periods, we believe this shift demonstrates their readiness for difficult dialogues about hard history. These same questions may come up in the upper elementary, middle school, and high school classrooms we are preparing teacher candidates to step into one day, and they need to be prepared to handle challenging questions and the conversations that follow.

We model difficult dialogues in our Social Studies methods courses to equip preservice teachers to have hard conversations about history with their future students. As we shared in this article, educators should prepare their students to engage in difficult dialogues by creating a safe classroom community, teaching students to activate listening and critical-thinking skills, and leading students to evaluate their own thinking and biases before entering challenging conversations. Teaching through inquiry, modeling primary source analysis, and encouraging students to use texts, oral histories, photographs, and visual sources as evidence when responding to challenging questions allows students to participate in difficult dialogues in the classroom without it devolving into a shouting match (Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning n.d.). While we do our best to prepare effective Social Studies teachers and fully acknowledge the challenges educators face today, we hope the strategies presented here will encourage them not to back down from teaching challenging topics out of fear or lack of knowledge.

Works Cited

Bronstein, Erin A., Kristy A. Brugar, and Shanedra D. Nowell. 2023. All Is Not OK in Oklahoma: A Content Analysis of Standards Legislation. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas. 96.1:33-40, https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2022.2158775.

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning. n.d. Difficult Dialogues. University of Connecticut, https://cetl.uconn.edu/resources/teaching-your-course/leading-effective-discussions/difficult-dialogues.

Christensen, Linda. 2012. Burned Out of Homes and History: Unearthing the Silenced Voices of the Tulsa Race Riot. Rethinking Schools. 27.1:12-18, https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/burned-out-of-homes-and-history-unearthing-the-silenced-voices-of-the-tulsa-race-riot.

Colbert, Brandi. 2021. Black Birds in the Sky: The Story and Legacy of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. New York: HarperCollins.

Crowe, Kweku Larry and Thabiti Lewis. 2021. The 1921 Tulsa Massacre. What Happened to Black Wall Street. Humanities. 42.1, https://www.neh.gov/article/1921-tulsa-massacre.

Ellsworth, Scott. n.d. Tulsa Race Massacre. The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=TU013.

Facing History and Ourselves. 2016. Preparing Students for Difficult Conversations. Facing History and Ourselves. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/preparing-students-difficult-conversations.

Gara, Antoine. 2020. The Baron of Black Wall Street. Forbes Magazine. June, https://www.forbes.com/sites/antoinegara/2020/06/18/the-bezos-of-black-wall-street-tulsa-race-riots-1921.

Hive Learning. n.d. Affinity Bias and You: Evaluate Your Inner Circle. Hive Learning, https://www.hivelearning.com/site/resource/inclusion-works-workouts-for-antiracism/affinity-bias-and-you-evaluate-your-inner-circle.

John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation..n.d. Stories About the 1921 Race Massacre: The John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation Documentary Project. John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, https://www.jhfcenter.org/1921-race-massacre.

Johnson, Annemarie. 2009. Mentor Text Background. Teacher2Teacher Help (blog), https://www.teacher2teacherhelp.com/mentor-text-background.

Johnson, Hannibal. n.d. Greenwood District. The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=GR024.

Latham, Jennifer. 2017. Dreamland Burning. New York: Little Brown and Company.

Levine, Ellen and Kadir Nelson. 2007. Henry’s Freedom Box. New York: Scholastic Press.

Library of Congress. n.d. Teacher’s Guides and Analysis Tool. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/programs/teachers/getting-started-with-primary-sources/guides.

Library of Congress. n.d. Getting Started with Primary Sources. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/programs/teachers/getting-started-with-primary-sources.

Neuhaus Education Center. 2023. Connect, Correct, Collect Chart. Neuhaus Education Center, https://www.neuhaus.org/wp-content/uploads/Connect_Correct_Collect_Chart.doc.

Oklahoma Historical Society. n.d. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Oklahoma Historical Society, https://www.okhistory.org/learn/tulsaracemassacre.

Oklahoma State University Library. n.d. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. Oklahoma State University Library, https://library.okstate.edu/search-and-find/collections/digital-collections/tulsa-race-riot-of-1921-collection.

Potter, Lee Ann. 2011. Teaching Difficult Topics with Primary Sources. Social Education. 75.6:284-90.

Schwartz, Sarah. 2021. Map: Where Critical Race Theory Is Under Attack. Education Week, June, http://www.edweek.org/leadership/map-where-critical-race-theory-is-under-attack/2021/06.

Thomas, Elizabeth. 2021. Emma Gurley. In Women of Black Wall Street, ed. Brandy Thomas Wells, https://blackwallstreetwomen.com/emma-gurley.

Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. n.d. Audio Recordings from Survivors and Contemporaries. Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/audio.

Voices of Oklahoma. n.d. Tulsa 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma Race Massacre. Voices of Oklahoma, https://voicesofoklahoma.com/topics/1921-tulsa-oklahoma-race-massacre-oral-histories.