James Bowen, March 22, 2018. Courtesy Sean Scheidt.

Let me tell you about my cousin James. First of all, he was almost 50 years older than me and we were actually like fourth cousins, once removed. I think. Anyway, from the time my Aunt Dorothy—who is actually not my aunt, but also a distant cousin, a couple of times removed—took me to Baltimore’s Northeast Market to visit James’ bakery as a kid, he was “my cousin James.” He saw us walking up and said, “Here come the Sampsons!” Aunt Dorothy looked at me and said, “See, here’s some of your people.”

Lumbees do this thing where we know and acknowledge distant relations right on down to umpteenth cousins, and oftentimes even just other Lumbees with no known familial ties to us, only cultural ones. “Hey Cuz!” is what we say. And, “Who’s your people?” If we don’t already know, we have this need to find out. But James really was my people.

Extremely pared down Sampson family tree with persons mentioned in this story highlighted to illustrate the kinds of complex networks of Lumbee kinship we honor. Designed using www.familyecho.com.

James was rail thin. He had close-cropped, salt and pepper hair that was more salt than pepper. If it grew out a little bit, you could tell it was wavy. He had blueish eyes. Thinking about it now, that color may have come with age. They were probably once brown. He almost always wore a ball cap and a collared shirt and nice pants with a belt and Oxford shoes but was usually covered in flour and icing from the bakery. If he was working, he wore an apron too.

His nickname was “Rat” and that’s what most people called him. He never learned to read or write, yet somehow knew everything about everything. For example, I once had occasion to visit the West Wing of the White House for work. James told me exactly how it was laid out, from memory. He knew because he had painted the Oval Office some decades before, when he worked as a painter. Before he became a baker. Before he grew old.

James was gentle and easygoing. He liked to walk. He liked to drink. He invented his own language and spoke it mostly when he was drinking. He liked to tell stories. He could “blow the fire out” of burns.1

By the time I got to be close with his daughter, my cousin Rosie who is much closer to my own age, James was in his early 70s. Rosie and I have had many adventures together over the years and James was along for most of them, but sometimes he would go off on his own. Like once, we were at the Fells Point Festival and James left us to go for a walk. We found him hours later, in a Greek bar, reminiscing on the phone with an old friend in Athens. He was just that way.

Everybody knew him. Everybody loved him. He remembered everybody from every time in his life and always wanted to know how they were doing.

Born in 1935, in Saddletree, North Carolina, in the Lumbee tribal territory, James was the son of sharecroppers. By all accounts, sharecropping was brutal. To make matters worse, there was also tri-racial segregation in that part of the world then. Imagine three separate school systems—one for white kids, one for Black kids, and one for Indians. Imagine three sections in the movie theaters. Imagine not having any time or money to go to the movies, or even school. James lived it. He came to Baltimore for the first time as a young man, in 1948. Like so many of his generation, he left home seeking work and a better quality of life.

Baltimore was the most popular destination by far. By the mid-1950s, anywhere from 2,000 to 7,000 Lumbee Indians were living in a small area on the east side of town that bridges the neighborhoods of Upper Fells Point and Washington Hill. In those days, they called it—affectionately—their “reservation.” There, they established churches and businesses and what would become the Baltimore American Indian Center. They descended on businesses that already existed. They sent for their relatives, housed them, and helped them find their way when they arrived. For some decades, this part of the city functioned as a space of cultural autonomy for the Lumbee, where they could be around people who looked like them and talked like them and understood where they came from. They made it their home away from home.

Then came the uprising in 1968, following the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Then came Urban Renewal in the early 1970s, which had already been in the works well before this Indian community was established. Of course, there was also upward mobility and other reasons folks moved away, but those two events transformed the physical landscape and marked the end of an era. Afterward, “the reservation,” as such, was no more.

To this day, Baltimore is still home to one of the largest populations of Lumbee tribal members living outside North Carolina, but most of us are scattered across southeastern Baltimore County, where I have lived since I was born, in 1983. And most Baltimoreans have no idea there ever was a “reservation” in the city or that there is an American Indian population in the area at all. The Baltimore American Indian Center and South Broadway Baptist Church, two enduring cornerstones of the community, are still open and somewhat active in the old neighborhood. Like many Baltimore Lumbees, I grew up visiting them, although we had to drive to get there.

In my lifetime, there were a couple of our places left on the former “reservation,” like the Indian Center’s daycare and Native American Senior Citizens building on Lombard, for example, which was sold in 2017. The building is still there, but it’s leased by a drug rehabilitation program now. A Native geometric design painted around the doorframe remains. Then there are places that live on in infamy, like the Volcano bar, which used to be at the corner of Ann and Fairmount and was said to erupt (with violence) every weekend. If you go to that corner today, you can’t even tell where a bar would have been. And then there are all the places my generation and those younger just wouldn’t know about because they were gone before our time—from the landscape and from public memory.

Realizing that there must have been many of these places, in 2018 I convened a group of Lumbee elders to help me piece together what had been “the reservation.” I had already been handed this 1969 map entitled “The Lumbee Community in Baltimore,” drawn by a white anthropologist for a federally commissioned report.

Map of the Lumbee Community in Baltimore included in John Gregory Peck, Education of Urban Indians: Lumbee Indians in Baltimore, National Study of American Indian Education, Series II, no. 3. Washington, DC: Office of Education, Bureau of Research, Aug. 1969.

I was excited to share the map with the elders. I handed out copies and said, “Look, I found your reservation!” The elders did look, and they were not excited.

Lumbee elders discuss Peck’s Map (l-r Howard Redell Hunt, Mattie “Ty” Fields, Jeanette Jones, Heyman Jones), March 22, 2018. Courtesy Sean Scheidt.

They said the map was “all wrong” because so much was missing. So I handed out pens and asked if they could make corrections, but they decided to draw their own maps instead.

Jeanette Hunt looks at Peck’s Map, March 22, 2018. Courtesy Sean Scheidt.

In conversation with one another, going alley by alley and street by street, they reconstructed “the reservation” of their youth on paper.

Jeanette Jones leads discussion while holding a hand-drawn map of “the reservation,” March 22, 2018. Courtesy Sean Scheidt.

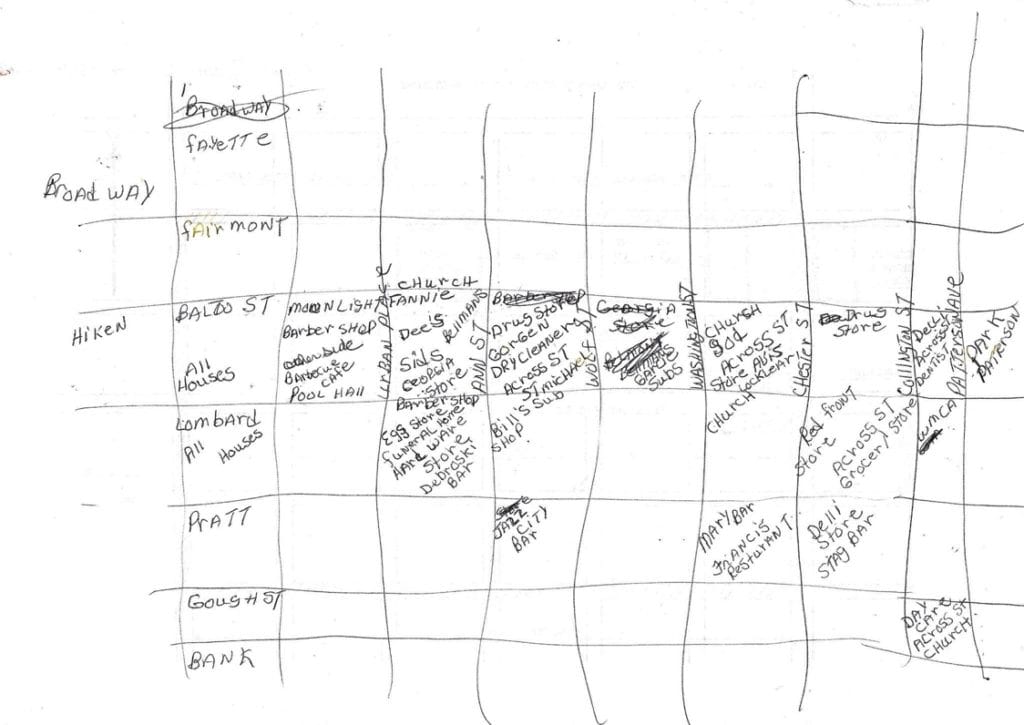

Jeanette Hunt’s hand-drawn map of “the reservation,” March 22, 2018. Courtesy Jeanette Hunt.

It’s easy to see the difference in the volume of information comparing these two maps. The elders’ map has so much more information. However, if each square of the elders’ map is intended to represent a city block, it’s hard to tell exactly where the named sites would have been on each block. I told them so. They said what I should have done was print a big, blank street map that we could have marked up together, so we tried that the next time we gathered.

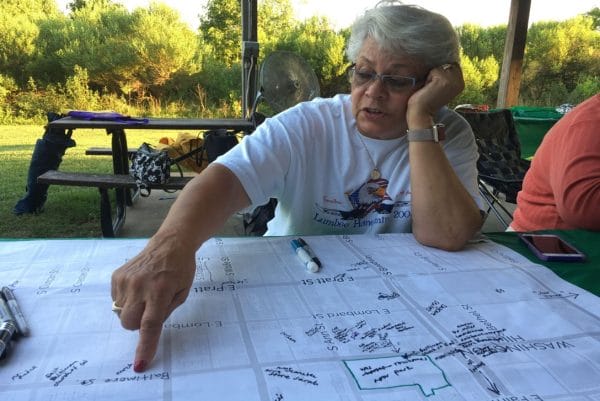

Jeanette Jones pointing out an important location on the former “reservation,” July 10, 2018. Photo by Ashley Minner.

Still, I was having a hard time correlating the information the elders were giving me to plot on the big, blank street map with the neighborhood I know from life. I told them I didn’t think I was going to be able to understand where things used to be until we physically went to the neighborhood together so they could point the places out. This led to several trips to the former “reservation” with different elders, including James.

Remember him? This is a story about my cousin James.

I spent one whole day riding around with James.2 We rode because, like me and most of the elders who worked on this project, James had been living in Baltimore County for years and years, miles away from the old neighborhood. Not walking distance. Also, by then, he was not as steady on his feet as he once was. He held my hand for support between the front door of his house and my car.

As he got in, we made small talk. I said, “You know, for as much time as I spent over here, I had to use the GPS to get here.” He said, “Well, you ain’t been here in a while.”3 “I know,” I said. “Y’all painted the house, didn’t you? It used to be white?” “Yeah,” he said, “The wind blowed them shingles away and I ain’t never put ‘em back. I got to buy some.” I laughed and asked, “Are you getting up on the roof?” “No! I don’t go up there,” he said. “I remember what [my wife] told me. I put a roof on that house one time and I used to climb and go. It still lingers in my mind and come back… She say, ‘One day, you ain’t gonna be able. You better do it while you can.’ And that’s true. It happens. I didn’t know I was ever gonna get old. I thought I was gonna stay at one age. Don’t you? Do you think about growing old?” As I reached for words, he answered for me. “Not really.”

“Well, where you wanna go to?” I asked. “I’m goin’ ridin with you! Anywhere you want to go. What you want to do is what we’re gonna do for a while,” he answered. So we headed for “the reservation.”

[At this point, readers may appreciate a map to reference.]

[At this point, readers may appreciate a map to reference.]

We came in on E. Baltimore Street, took a left on Broadway and rode all the way down to the water, pausing to glance at places like old Sadie’s bar, the Broadway Café—the bar his late wife’s family once owned, a tire shop Indian guys had on Thames Street in the 60s, James’ first apartment in the city on Ann. We rode through the neighborhood slow, again and again, different ways, as he told me all about adventures I had missed, people he used to know, more places he used to live, bars he used to drink in, buildings he had worked on, his painters’ union hall. We were time traveling—moving through histories of not only our own community, but also of the English and the Germans and the Irish and African Americans and Poles and Greeks and Russian Jews who had called this place home. Hell, even the pirates and privateers are still around when you realize, as we did, that cities are just full of ghosts. Ancestors of the Piscataway who had camped here and other Indigenous peoples who had passed through left something of themselves. Baltimore is totally haunted. Every absence points to a presence.

Eventually, we branched out and found ourselves on Eastern Avenue at Washington Street. James got quiet and stared out the window like he was searching for something. A few moments passed in silence before he said, “I could get lost down here anymore.” I looked over at him and said, “You always know where you are.” “I know where I is,” he said, “but I used to know every corner place and everything down here and they all knowed me.” I said, “Seems like they still do.” James got quiet again. “They know of me now.” Laughing, I said, “You’re a legend!” James smiled and said, “I got a lotta friends in this town, baby.”

James Bowen drinking coffee in Sip & Bite, November 22, 2019. Photo by Ashley Minner.

When we had run out of “reservation” to revisit, it was lunchtime, so we decided to stop in at Sip & Bite, in Canton, to look for one of those friends. James had hoped to run into the semi-recently retired owner, George Vasiliades, who had started as a dishwasher in the Moonlight restaurant, in the heart of what had been “the reservation.” Unfortunately, Mr. George wasn’t there that day. We still got a good conversation in with the waitress, who asked if we were from North Carolina and proudly proclaimed she had grown up with Lumbee Indians in the city.

Later, we took a ride to South Baltimore, to visit a couple of more former Indian churches. I pulled the car up to the curb outside the Brooklyn Church of God. Baltimoreans are notoriously suspicious of strangers lingering in their neighborhoods. A woman came to the doorway and hollered out, “Can I help you?” “I used to go to church here!” James hollered back.

After that, James wasn’t ready to go home, so we made our last stop the Baltimore Museum of Industry, in Federal Hill, which, according to its website, “inspires tomorrow’s worker by celebrating yesterday’s worker. Just like these real people doing real jobs,” the Museum of Industry is “not varnished or slick or Hollywood,” but “an uncommon look at common working men and women who literally laid the groundwork for everything that Baltimore is and can be” (Baltimore Museum of Industry). Exhibits feature real tools in staged settings of trades once prominent in the city. One can visit a cannery, an umbrella factory, a print shop, a garment shop, a machine shop, a pharmacy, and an automotive exhibit with real cars on the floor of the museum.

James, who had never been to this museum before, was curious to see everything on display. Of course, having been a baker since 1979, he was particularly interested in a bakery exhibit. He proceeded to handle various tools laid out on a counter, then banged on a large, free-standing metal drum. It made a startlingly loud noise. I started to whisper about a “no touching” policy posted on the wall but stopped short. James was excitedly telling me which of the tools he once had, and which were still being used in his family’s bakery. To him, the stuff was just stuff. Who was I to tell him what to do or not do with it? Wasn’t this museum a tribute to him and his labor, after all? Once or twice, staff passed through and saw James handling the artifacts. They smiled and said nothing. If they had paused long enough, he could have taught them a thing or two.

What must it feel like when the neighborhood of your youth is transformed beyond the point of recognition, when your people move away and slip away until you don’t see anyone you know there anymore—until you, yourself, are no longer known? What must it be like when the tools of your trade become museum displays, not to be touched—when the trades themselves have passed or are passing away? What does it mean to grow old in East Baltimore when you’re a Lumbee Indian?

The author and James Bowen, November 7, 2019. Photo by Ashley Minner.

James died this year. It was a Wednesday evening. He was in hospice, but he hadn’t been there long. Rosie said he waited for me to arrive. I think that’s true because when I walked in, I said, “Hey Cuz! I’m finally here!” Then he started taking deep, gasping breaths. A few minutes later he was gone.

Except he isn’t.

How could he be? As long as we’re alive, James will be too. As long as East Baltimore stands, he’ll be present. We’re walking in his footsteps, retelling his stories, speaking his language, keeping him around. We outline the spaces he used to fill with his body and know that indeed every absence points to a presence.

Ashley Minner is a community-based visual artist from Baltimore, Maryland, and an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. She earned her MFA in Community Arts from Maryland Institute College of Art and her PhD in American Studies from University of Maryland College Park. In addition to maintaining her artistic practice, Ashley works as an Assistant Curator for History and Culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC. ORCID 0000-0002-5122-5176

Note Regarding Images: Informed consent was obtained from all creators of images included in this essay, as well as those pictured.

Links to Resources, including Urls referenced in the article

The Baltimore “Reservation” website https://www.baltimorereservation.com

Baltimore Reservation on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/baltimorereservation

Baltimore American Indian Center website https://baltimoreamericanindiancenter.org

Print guide to East Baltimore’s Historic American Indian “Reservation” https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/60b453cbcf5d591709ab655b/6191503c5227a135e796bfd4_East-Baltimores-Historic-American-Indian-Reservation-Map-and-Booklet-2021.pdf

Guide to Indigenous Baltimore cellphone walking tour app for Apple https://apps.apple.com/us/app/guide-to-indigenous-baltimore/id1581162134

Guide to Indigenous Baltimore cellphone walking tour app for Android https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.pocketsights.IndigenousBaltimore&hl=en_US&gl=US

Native Land https://native-land.ca

United States Department of Arts and Culture (USDAC) Honor Native Land Initiative https://usdac.us/nativeland

Maryland State Arts Council Land Acknowledgement Project Overview and Resource Guide https://msac.org/media/760/download?inline

Baltimore Museum of Industry https://www.thebmi.org

Endnotes

- It’s exactly what it sounds like. See https://unmaskedhistory.com/2019/09/29/folklife-the-faith-healing-tradition-of-talking-out-the-fire.

- The next section is an adapted excerpt of my dissertation. See Ashley Colleen Minner. Revisiting the Reservation: The Lumbee Community of East Baltimore.PhD Dissertation. University of Maryland College Park, 165–68.

- All quotes from this conversation are excerpts of James Bowen interview with Ashley Minner, November 22, 2019, Part I, Baltimore, Maryland, transcript.