This screenshot comes from the opening video of the storytelling PerformancerUS project cowritten by students of The Ohio State University.

Across the United States the Covid-19 pandemic presented many challenges and intensified racial tensions and health disparities in many communities, particularly minoritized communities. This public health crisis exposed and exacerbated many of the known deficiencies in the U.S. health system and highlighted enduring racial and ethnic health disparities. From the Northeast to the Southwest, the case fatality rate of African American and Latina/o/x populations outpaces that of other racial and ethnic groups (Dwyder 2020, Mays and Newman 2020). Racial disparities in disease transmission and death are multifactored, including a history of abuse from health institutions. For the BIPOC community, the failure to receive adequate care has led to mistrust of these institutions and awakened a history of collective and traumatic loss, which inevitably asks us to re-visit the past. The oral narratives, performances, and engaged pedagogy described here provide resources to educators who seek to incorporate these perspectives into their classrooms. In this article, find questions to help you and your students understand a community’s access to culturally relevant information (i.e., in Spanish for Latino/a/x communities) and awareness of resources. The co-created product from our research and performance project, PerformancerUS, 1 contributed to my university students’ understanding of how the virus has affected the Latina/o/x community, including how they dealt with fear about the disease and death, as well as other issues related to mental health.

Background

In New York City, Latinas/os/x accounted for over a third of all mortalities with known race and ethnicity, a picture that reflects similar outcomes across the U.S. (NYC Health 2020). The uneven impact of Covid-19 on Latina/o/x populations throughout the country is evident in an increased likelihood of succumbing to the virus and in the social and economic spillover effects of the crisis. Latinas/os/x have been shown to be the hardest hit by pay cuts and job losses and are more likely to view the crisis as a major threat to their personal health, financial situation, and day-to-day life in their local communities (Krogstad, Gonzalez-Barrera, and Lopez 2020; Krogstad, Gonzalez-Barrera, and Noe-Bustamente 2020). It is clear now that many Latina/o/x peoples who work in factories and as farmworkers were not provided timely and proper personal protective equipment, and, equally important, our community had little to no access to information and care in Spanish. As an immigrant Latina professor of Spanish, I am frustrated and angered by this lack of language access. As of 2020, Black and Latina/o/x deaths account for 34 percent of deaths from a population who represent 12 percent of the U.S. (Holmes et al. 2020). The full impact of these cumulative disparities will not be fully understood for many years.

To document this moment, a group of my former undergraduate students at The Ohio State University (OSU) and I decided to collect and transcribe personal experience narratives and oral histories of Latina/o/x peoples across Ohio about their experiences to offer a platform to our community to tell their stories and to build a performance to inform others how each story could collectively represent this very diverse community. This means that the Latina/o/x community can be bilingual, Spanish and English, or monolingual English or Spanish speakers; they are immigrants (recent or not), U.S.-born, racially and ethnically diverse, all genders, young and old. Each interview was scheduled and recorded using pandemic protocols such as use of masks, physical distancing, and centering narrators’ comfort, which in some cases included recording outdoors, with masks on, or via Zoom. Narrators shared their experiences living under quarantine orders, protecting families and friends from infection, and confronting illness. The interviews expressed a collective voice that reflects unique impacts of social distancing, social and economic lockdown, and illness on Latinas/os/x daily lives. At the early stage of collection, it was evident that experiences varied primarily among professions and whether narrators spoke English.

The resulting performance draws on a unique arts and humanities methodology already in place at OSU. The collaborative co-creation of the performance engages with and added to the growing oral history archive about Latinas/os/x in Ohio, Oral Narratives of Latin@s in Ohio (ONLO). ONLO documents life stories of the Latina/o/x community across generations, decades, and heritages. ONLO began in 2014 and features narratives from throughout the state. In 2019, the archive was enriched through the addition of our performances, four to date.

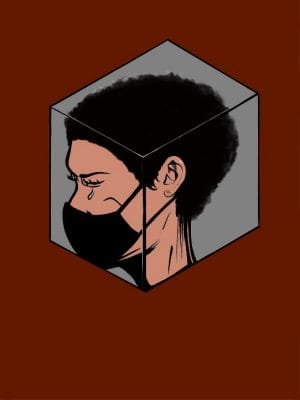

Figure 1. Mask, by Heder Ubaldo.

Performance and Counternarrative

Following Della Pollock, we viewed a natural link between performance and oral history, in which Pollock contends that “insofar as oral history is a process of making history in dialogue, it is performative” (2005, 2). The PerformancerUS project brings Latina/o/x personal narratives in Ohio to life through interactive performance between audience and speaker. The folklorist Richard Bauman defined performance as “a mode of communication, a way of speaking, the essence of which resides in the assumption of responsibility to an audience for a display of communication skill, highlighting the way in which communi-cation is carried out, above and beyond its referential content,” but performance too is an intentional and conscious decision to embody and share an experience, one that is transformative to the performer and the audience. He adds that for “the audience, the act of expression on the part of the performer is thus laid open to evaluation for the way it is done, for the relative skill and effectiveness of the performer’s display. It is also offered for the enhancement of experience, through the present appreciation for the intrinsic qualities of the act of expression itself” (1986, 3). Hence, a key component of our performance approach is to engage the audience and receive feedback, to foster a communal experience between audience and performers so that both parties feel as part of one shared expression.

The oral history/performance approach has been used successfully to unearth critical race counter stories among Latina/o/x students in the Midwest (Alex and Foulis 2020, Foulis and Alex 2021). The project applied this methodology to uncover and provide greater insights into the experience of the Covid-19 pandemic in Ohio and to share these insights with frontline health professionals and other public heath entities interested in increasing access to minoritized communities. The performance is publicly available and has been shared with classes focused on health and Latina/o/x topics. The transcribed and translated narratives were the basis for a collaborative cowritten creative performance with undergraduate students for the Spring of 2021—all of us Latina/o/x. It was produced via video due to limitations on gathering in large groups. This was our second performance as a group, so although this work centers group gatherings to workshop each story and team-building activities, our meetings via Zoom worked well, since we had worked together before. Students and I worked with the transcribed narratives to identify common themes and to create a script that included words and phrases directly from the interviews while also weaving in each ensemble member’s experiences. Through our words, narrative expressions, semi-fictionalized storyline, and visual art, we expressed our community’s social isolation, mental health concerns, stay-at-home orders, death and virtual funerals that prevented or dwarfed proper burial rituals, and grief.

Our video performance added a new component to our live collaborative creation, which allowed us to create and incorporate further meaning with editing, framing, sound, graphics, pacing, and lighting. For example, we interlaced narrative segments with student-created images (see figures 1-4), words on a black screen, and silences, which added emotion and meaning through editing. If used in the classroom, the video performance will show students enrolled in Spanish, Latina/o/x Studies, and healthcare classes, such as nursing, a different way of talking about and understanding experiences of a pandemic for this community. Indeed, curating the performance and providing in-depth discussions to students who view this video offers an opportunity to document their own reactions to the performance, and widen their understanding of this community

Our collaborative scripting and creating the performance presented different opportunities for us, as listeners first and co-creators second, such as the chance to reflect on stories and experiences of our own community. Although we were all Latina/o/x, our experiences were different given our access to employment accommodations, school structures, and families, some of whom live in Latin America. The script was messy and complicated because it was difficult to see a cohesive story: We all experienced the pandemic—within the global protests on race inequality—in multiple ways. While the storyline follows a collective fictional narrator, each statistic and quote from original transcripts expressed factual numbers and original messages and experiences, including the raw nature of speech complicated by the realization that one might die alone at a hospital or have no agency in health care decisions because no one else speaks Spanish. Yet, what was always clear to us was that immigration status and language access were key determinants of health outcomes, and even the very palpable possibility of death for Latina/o/x peoples.

Listening to the Stories

The performance begins with the following words in Spanish and English on a black screen with white letters, appearing one by one followed by our voices. Each word is pronounced.

Screenshot from video performance.

The pace is slow, allowing the viewer to listen, read, and preview performance themes. A more concise, direct introduction follows before we begin telling the collective story of the pandemic:

La pandemia del coronavirus ha afectado a los latinos 3 veces más que a las personas blancas en los Estados Unidos. Es la comunidad con mayor índice de mortalidades. Más de 60 mil de los nuestros han muerto este año en Estados Unidos. Poco más del 70% de ellos fueron nuestros padres y madres y casi 45% fueron nuestros abuelos. Somos la comunidad que ha muerto más. Que ha muerto at a higher rate because we have no other choice. Because don’t have the privilege to stay home for two weeks and not have to work. We don’t have it. We never had it. And we won’t have it any time soon.

Although the transcription and translation of the script is available, sharing the performance in both languages allowed us to stay true to the experiences of our narrators and ourselves. Additionally, for viewers who might not be bilingual, the need to view and read the translated script can mimic, in a small scale, the experiences of patients at hospitals that did not provide information in Spanish or an interpreter. If educators use the video performance to discuss health disparities, they may decide whether to use the transcript and translation the first time that students view it. They can also have students view the video without any translation, or have students read the transcript and translation to understand the content and then view the video later. Each approach can generate conversations regarding language access as a health equity issue and each approach will develop different levels of empathy among viewers. In addition, discussions about race as a public health issue can further explore the connection between language and race as social determinants of health outcomes.

Figure 2. I can’t breathe, by Oscar Fernández.

The performance weaves the story of two women, a working-class mother and daughter, who express how each received information about the pandemic. The storyline follows their experiences with the news, misinformation, mask mandates, isolation, mental health, and more. Interwoven are the stories of other community members to show how different groups had different concerns, including the undocumented community, LGBTQ+ people, artists, and essential workers, many of whom lived with family members of multiple generations. Short clips gave data from the governor’s daily press updates and information about the murder of George Floyd. At times, the interlaced stories seem chaotic—too much information, too little time to digest—but this reflects the anguish many minoritized communities were experiencing as they saw the number of cases rise, the protests, and hate crimes against the Asian community. For instance, the performance includes the following information, staring at minute 22:30:

Protests in Columbus started on May 28, 2020, demanding justice for George Floyd, killed by officer Derek Chauvin who knelt on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds during an arrest the day before. The Protest continued until the end of June.”

This is followed by each ensemble member saying the words “I can’t breathe, No puedo respirar.”

Indeed, this part of the performance is a collective mourning about police brutality against Black and Brown communities and a metaphor of the effects of the virus, which in severe cases resulted in intubation and death. The performance, multiple voices, and images speak of “both ephemeral and tangible ways” (Otero and Martinez-Rivera 2021, 5), in which remembering and honoring these experiences pushes us to understand different identities, languages, and social positionalities. Indeed, each section can generate discussions of health equity, racial violence, and the possibilities for solidarity among different communities.

While this part of the performance is in constant dialogue with local and global social injustice, one of the most powerful moments is when the mother gets Covid and must go to the hospital. She expresses hesitation, but we witness her experience of isolation because no visitors were allowed and because no one cared for her in Spanish.

Figure 3. Los Contagiados, by Heder Ubaldo.

En agosto, yo fui al hospital. No quería ir, en verdad no quería ir, ya no me daba la respiración y andaba agitada. No me caía nada la comida, nada, no me llegaba el sabor, no comía, entonces, dije “¿Sabes qué? Llama al hospital.” Llegué allí, luego me internaron. Y luego me hicieron el test del Covid-19, y me dijeron “Tienes Covid-19, te vas a quedar.” ni modo, entonces me quedo, y dijo te vamos a checar tus pulmones. Y salió que tenía ah, este, Covid-19 en los pulmones, que se llama como neumonía, viene del Covid-19, se llama Covid-19. Y me llevaron para el cuarto, y yo decía “Pues, no, no sé el inglés.” Me metieron en un cuarto todo frío, estaba frío. Y ya yo decía un poquito en inglés, decía “Eh, está cold. Tengo-” decía, “Tengo frío.” Y no me entendían. Le decía “Le puedes abajar el este, el cuarto está muy frío, le puedes abajar porque no aguanto, aquí está muy frío, y no, no podemos.” No, no, no hablaban nada de español. Ni uno hablaba español. Nadie habla español. Y tenía que hacer a señas, [porque] no me entendían. No me entendían nada, y para la medicina, pues tampoco no me entendían nada. Fui al baño, no me entendían nada, nada. No…el cuarto todo oscuro, está feo estar allí, feo. Está feo estar allí. (Italics for emphasis)

In August, I went to the hospital. I didn’t want to go, really, I didn’t want to. I couldn’t breathe anymore and I felt agitated. Food didn’t set well, not at all, I couldn’t taste it. I wasn’t eating, so I said, “take me to the hospital.” I arrived and they admitted me. And then they tested me for Covid-19, and they told me, “You have Covid-19, you are staying.” What are you going to do? So I stayed, and they told me they were checking my lungs, that it was pneumonia, from Covid-19, it was Covid-19. And they took me to the room, and I said “No, I don’t know English.” And they took me to the cold room. With some English phrases I said, “Um, it’s cold, I am…” I said, “I am cold.” But they didn’t understand me. I said, “can you turn it down (the cold temperature), the room is too cold, can turn (the cold) down, I can’t stand it, it’s really cold here,” and (they said), “no, we can’t.” No, no, no, they did not speak any Spanish. None did. Nobody spoke Spanish. So I have used gestures because they did not understand me. They did not understand me in the least. And the medication, well, they did not understand me either. I went to the bathroom, and they did not understand me in the least. No… the room was dark, it was scary to be there, scary. It was scary to be there. (Translation by the author)

Her recollection reflects how she came to understand her disease and had to be admitted. The cold hospital room and that no one explained what was happening in Spanish added to her isolation and despair. She continues:

Las enfermeras, las enfermeras no me atendían.

¿Por qué no me entendían?

Con el doctor, tampoco. El doctor no hablaba español.

Le tenía que hablar y localizar a mi hija para decir qué es lo que está pasando.

Me ponían algo. Es más, imagínate, me ponían algo, y yo no sabía.

No sabía ni qué me ponían algo a la vena pues, no sabía ni qué preguntarles “Oye, ¿qué me estás poniendo?” ¿Cuántos miligramos me estás poniendo?” “¿Para qué es eso?”

Tú crees cómo me sentía yo. ¿Para qué es eso?

A lo mejor me van a poner algo, pensaba “A lo mejor me van a poner algo para morirme. (Italics for emphasis)

The nurses, the nurses did not understand me.

Why didn’t they understand me?

The doctor didn’t either. The doctor did not speak Spanish.

I had to talk and reach me daughter to tell her what was happening.

They gave me something. Yes, can you believe it? They gave me something and I didn’t know what it was.

I didn’t know what they were putting in my vein, I didn’t even know what to ask them, “Hey, what are you giving me? How many milligrams are you giving me? What is this for?”

Can you believe how I felt, what is this for?

Maybe they were giving me something, I thought, “maybe they are giving me something to die.’ (Translation by the author)

Figure 4. Despair, by Heder Ubaldo.

Conclusion

The lack of language access for many meant death, or a near-death experience. Without communication patients cannot provide relevant information, nor do they receive clear information. Studies show how language access during Covid-19 had high risks due to the urgency of respiratory distress and end-of-life decisions (Aguilera 2020, Ortega et al. 2020). As Hurtado notes, “Miscommunication can pose different problems in the Covid-19 unit… especially because family members are not allowed inside. [Also,] while working in the hospital, some medical staff are culturally insensitive to patients” (Hurtado 2020). This section of the performance allows for additional discussions about language identity and language ideologies. It can also lead to talking about health care literacy, health practices—including the use of curanderos or homeopathic remedies—and diversity among cultures.

- Is providing information on patients’ preferred language enough to help them make decisions about their care?

- How does understanding the health care and financial literacy of patients help healthcare workers offer just and inclusive care?

- How does understanding diverse decolonial health practices like curanderas/os, remedios caseros, sobadoras, and rituals, as well as the role of religion, contribute to meaningful conversations about care between Latina/o/x patients and their healthcare providers?

The performance continues with constant interjections about the pandemic, mask mandates, and views from different groups. It ends with the personal perspectives of each ensemble member and what they lost during the pandemic, including trips, graduation ceremonies, and employment. The performance is a vehicle for bringing to light the voices and stories of the Latina/o/x community, but it is also an opportunity for each ensemble member to reflect about our own experiences and that of our families.

The audience is important to this performance. We typically begin and end with audience engagement, which becomes part of the performance. We ease into the performance with simple questions such as asking the audience to come up with a word that encompasses their experiences during the pandemic, or one or two things they missed the most during the stay-at-home orders. We told the audience the performance was primarily in Spanish, but we had the translation available to follow along. Different audiences provide different feedback and perspectives. We showed the video via Zoom and talked with our audience, so we know that despite limitations of a live performance, video can be a tool for continuing these conversations in the classroom and among different people. The impact derives from engaging with a multitude of audiences as we come together to witness the stories of Latinas/os/x from different parts of the U.S., yet with a common experience of living under quarantine and social distancing guidelines, and by developing cultural understanding of the challenges of being Latina/o/x in the times of a healthcare crisis.

The oral histories and narratives collected during the Covid-19 pandemic will serve as testimony that honors the lives of many who were affected socially, economically, and emotionally. The performance is a standing invitation to consider how limited English learners and minoritized population often bear the burden, and possibly fatal results, of limited access to information and an equitable healthcare system. The performance is also a vehicle for thinking about issues of equity, many centered on our understanding of Critical Race Theory— currently under attack—to engage our students and classroom in real conversations about the role of language, cultural, and social pluralities, in creating a socially just word.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all our narrators for providing your stories and perspectives during this difficult time. Your stories are so valuable to all of us. I want to highlight each ensemble member who collaborated with me for two years: Liz Morales, Lidia García Berelleza, Stefania Grisales Torres, Paloma Pinillos Chávez, Heder Ubaldo, Micah Unzueta, and Manuel Bautista. It was a pleasure working with each of you.

Elena Foulis is Assistant Professor at Texas A&M, San Antonio and has been directing the oral history project, Oral Narratives of Latin@s in Ohio (ONLO) since 2014. The project is an ongoing collection of over 130 video narratives, some can be found in her iBook titled, Latin@ Stories Across Ohio. Foulis’s research explores Latina/o/x voices through oral history and performance, identity and place, ethnography and family history. She is also host and producer for the Latin@ Stories podcast, an extension of her oral history project. This podcast invites audiences to connect and learn more about the Latina/o/x experiences locally, while amplifying the voices of the community everywhere. She co-hosted the Art and Sciences podcast, Woke Pedagogies. Foulis is an engaged scholar and is committed to reaching non-academic and academic audiences through her writing, presentations, and public humanities projects. ORCID 0000-0003-4184-44

Endnote

- The word PerformancerUS is a linguistic play that integrates the idea of performers with autoperformance, to suggest that we are performing our collective histories.

Works Cited

Aguilera Jasmine. 2020. Coronavirus Patients Who Don’t Speak English Could End Up ‘Unable to Communicate in Their Last Moments of Life.’ Time, April 15. https://time.com/5816932/coronavirus-medical-interpreters.

Alex, Stacey and Elena Foulis. 2020. Be the Street: The Performative and Transformative Possibilities of Oral History. US Latina & Latino Oral History Journal, 4.1:45–66.

Bauman, Richard. 1986. Story, Performance, and Event: Contextual Studies of Oral Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dwyder, Colin. 2020. New York City’s Latinx Residents Hit Hardest by Coronavirus Deaths.

NPR, April 16, https://www.npr.org/2020/04/08/829726964/new-york-citys-latinx-residents-hit-hardest-by-coronavirus-deaths.

Foulis Elena and Stacey Alex. 2021. On Loss, Gain, Acceptance and Belonging: Spanish in the Midwest. Spanish as a Heritage Language Journal. 1.1:39–64.

Holmes, Lauren, et al. 2020. Black-White Risk Differentials in COVID-19 (SARS-COV2) Transmission, Mortality and Case Fatality in the United States: Translational Epidemiologic Perspective and Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17.12:1–18.

Hurtado Leslie. 2020. Spanish Speakers with COVID-19 Left in the Dark About Their Care. Cicero, IL: Cicero Independiente, https://www.ciceroindependiente.com/english/spanish-speakers-with-covid-19-face-extra-challenges-in-hospitals.

Krogstad, Jens, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, and Mark Hugo Lopez. 2020. Hispanics More Likely Than Americans Overall to See Coronavirus as a Major Threat To Health And Finances, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/24/hispanics-more-likely-than-americans-overall-to-see-coronavirus-as-a-major-threat-to-health-and-finances.

Krogstad, Jens, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, and Luis Noe-Bustamente. 2020. U.S. Latinos Among Hardest Hit by Pay Cuts, Job Losses Due to Coronavirus,https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/03/u-s-latinos-among-hardest-hit-by-pay-cuts-job-losses-due-to-coronavirus.

Mays, Jeffrey. and Andy Newman. 2020. Virus Is Twice as Deadly for Black and Latino People Than Whites in NYC. New York Times, April 8, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/nyregion/coronavirus-race-deaths.html.

NYC Health. 2020. Age Adjusted Rate of Fatal Lab Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per 100,000 by Race/Ethnicity Group, : https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh /downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-04082020-1.pdf.

Ortega, Pilar, Glenn Martínez, and Lisa Diamond. 2020. Language and Health Equity during COVID-19: Lessons and Opportunities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. .31.:1530-35.

Otero, Solimar and Mintzi Auanda Martinez-Rivera, eds. 2021. How Does Folklore Find Its Voice in the Twenty-first Century? An Offering/Invitation from the Margins. In Solimar Otero and M.A. Martinez-Rivera, eds. Theorizing Folklore from the Margins: Critical and Ethical Approaches. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Pollock, Della.(2005. Remembering: Oral History Performance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Urls

Performance video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-FDs-3bHU2I&list=PLQ_40nND6CAMgJwUcjKV3A9kGuBpByktQ&index=1

Oral Narratives of Latin@s in Ohio https://cfs.osu.edu/archives/collections/ONLO