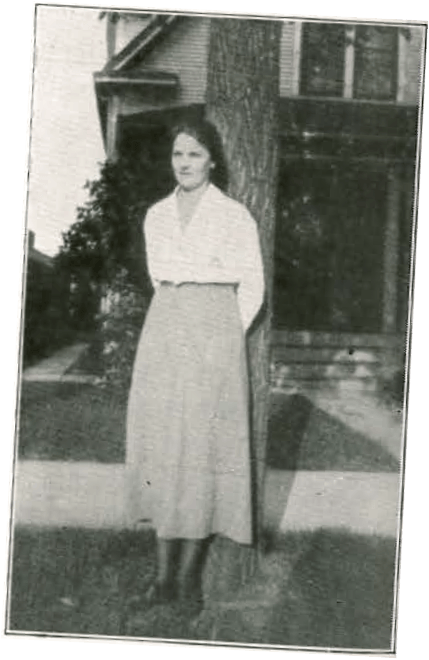

Signe Aurell standing in front of one of the Minneapolis homes where she lived circa 1919 (Bokstugan 1921, 26).

Following a 2019 performance in Sweden, the singer and musician Maja Heurling was approached by an audience member and recent migrant. “This is the first time I’ve heard a Swede telling the story that I carry inside,” they told her (Heurling 2022). The Swede who originally told the story, however, was not Heurling, but Signe Aurell, a Swedish immigrant who arrived in the United States in 1913. The grateful audience member had just seen a performance of “Irrbloss: Tonsatta dikter av Signe Aurell” [“Irrbloss: Songs from the Poetry of Signe Aurell”], based on a several-years long research project about Aurell, her poetry, and Swedish American working women in the U.S. Through a collaboration with folklorists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, this performance became part of a multimodal, artist-driven public folklore project to draw connections between historical and contemporary issues of immigration and challenge our understanding of migration by relying heavily on folkloristic research.

A Swedish American Will-of-the-Wisp

Signe Aurell was born on February 14, 1889, in Gryt, Sweden. She was one of six children of Anna and Andreas Aurell. Until her move to the U.S., she spent her life in northern Skåne (a region in southern Sweden), where her father worked as a schoolteacher. In 1913, Aurell began the lengthy journey across the Atlantic. After several weeks of travel in third class, she stepped off the SS Franconia in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 7, 1913. Settling in Minneapolis, Minnesota, she worked various jobs, including as a laundress and a seamstress. Between 1913 and 1920, Aurell had at least 12 addresses, many in and around the Franklin-Seward neighborhood, home to a large population of Swedes. Her frequent address changes are an indication of the unstable living conditions of the Swedish American working class (Cederström 2016b).

During her time in Minneapolis, Aurell began publishing poetry in the radical Swedish American press. Writing exclusively in Swedish, she began to make a name for herself as a lyrical poet capturing the lived experiences of Swedish working women. Writing not just about love and loss and a longing for home, but also about labor, she spoke to the working-class immigrant experience of many women like her (Cederström 2016a). And there were many women like her: Aurell was one of about 250,000 single Swedish women who traveled to the U.S. between 1881 and 1920 (Lintelman 2009).

In 1919, Signe Aurell self-published a book of poetry titled Irrbloss [Will-of-the-wisp] that she sold for $0.25 from her apartment in Minneapolis. Featuring poems previously published in the Swedish American labor press, as well as new poetry, the collection was well received, garnering positive reviews in Swedish and Swedish American newspapers (Cederström 2016b). But praise doesn’t pay the rent. A year later, in 1920, Signe Aurell moved back to Sweden. Exactly why is unclear, but a farewell written in Bokstugan, a Swedish-language newspaper published out of Chicago, Illinois, where she was a frequent contributor, placed the blame on economic troubles (Bokstugan 1920, 17). She would spend the rest of her life in or near her hometown in Sweden, publishing occasionally, but seemingly stepping back from her days as an activist, instead taking care of her parents in their old age. Aurell died on April 29, 1975.

Like so many other immigrants, Aurell came to the U.S. as a single woman and experienced unstable living and working conditions. And while hundreds of thousands of immigrants stayed, many, just like Aurell, eventually moved home; approximately 20 percent of Swedish migrants to the U.S. moved back to Sweden (Wyman 1993, 80). Yet the return of so many migrants is missing from not just the popular telling of Nordic migration, but also in the scholarly literature. In the popular imagination of Swedish America, Swedish migrants farmed the land, made lives for themselves, and lived the American dream. Stories of difficulties and failure, predatory employers, or crippling homesickness, on the other hand, are less common. Jennifer Eastman Attebery documents this scarcity by examining historical legends in local histories. Noting that while these histories are more nuanced today, if still imperfect, there has long been a palliative approach to telling the history of Swedish America that excused or downplayed the negative aspects and experiences of migration (2023, 54–5).

Aurell’s poetry, written by a Swedish immigrant for Swedish immigrants, deals with many of these difficulties head-on. She had direct experience, after all. While living in the U.S., one of her friends recalled that an employer refused to pay Aurell after she had washed all the clothes she had been assigned. In response, Aurell dumped the clothes back in the dirty water, walked out, and never returned (Engdahl 1961, 8). It should come as no surprise, then, that Aurell advocated for women to organize and unionize. Her poetry presented a vision for a better future based on direct action and a strong and just labor movement. But her experiences as a migrant weren’t limited to activism. She also wrote about missing home, missing her mother, and the difficulties of being an immigrant. All these themes were expressed in Irrbloss and were explored in a research project I conducted for several years, culminating in my dissertation, In Search of Signe: The Life and Times of a Swedish Immigrant (Cederström 2016b).

Since then, in collaboration with musicians like Maja Heurling and Ola Sandström in Sweden as well as folklorists here in the U.S., we developed a multimodal public folklore project to reconfigure and share that research with a broader audience. That story, Aurell’s story, the story that many audience members carry inside, is a story shared by immigrants in different times and in different places. It’s a story that challenges assumptions about historically “successful” immigration from Sweden to the U.S. and even challenges assumptions of contemporary migration from other countries to Sweden.

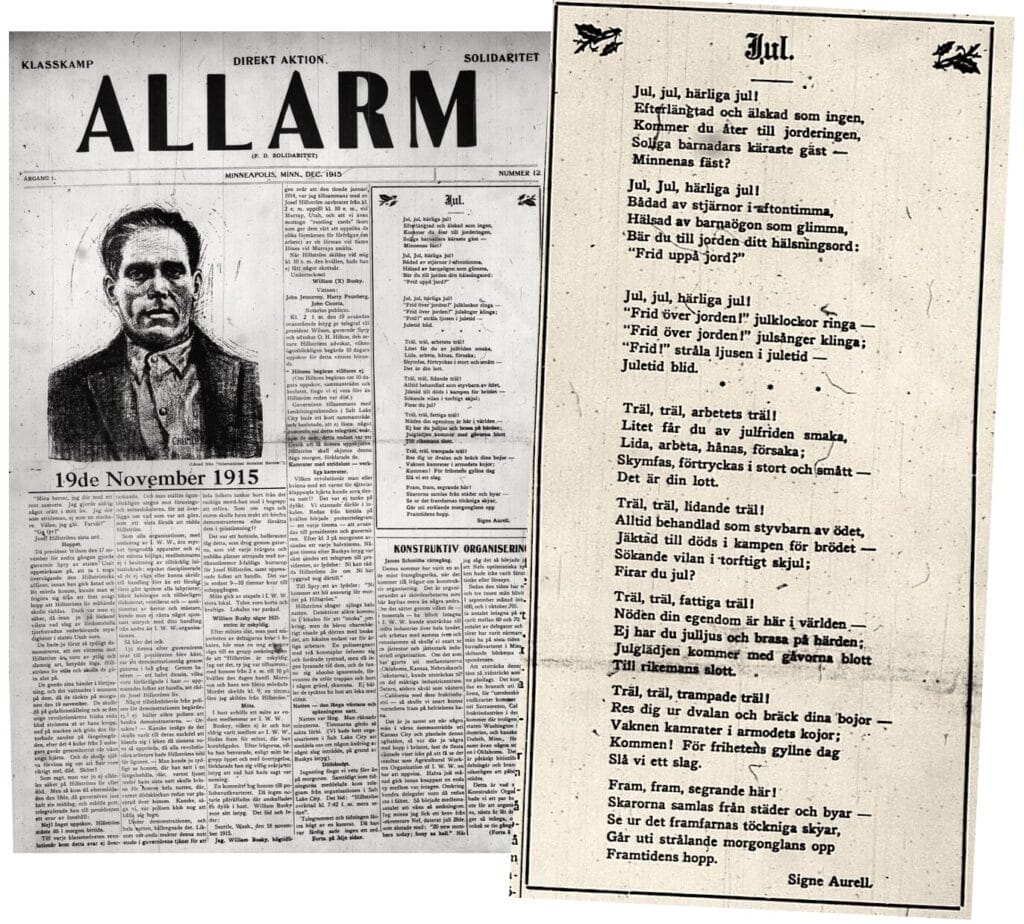

Signe Aurell’s first known published poem, “Jul” (Allarm, December 1915, 1).

From the Page to the Stage

In 2019, 100 years after the initial publication of Irrbloss, the folk singers Maja Heurling and Ola Sandström released their own Irrbloss, to quite a bit of acclaim in the Swedish press. The album features 12 of Aurell’s original 23 poems set to music and includes a 13th track, an instrumental piece also titled “Irrbloss,” written by Sandström. The liner notes include my short biography of Aurell in Swedish and English.

That album was years in the making. While conducting research about Signe Aurell in Sweden in 2015, I went to a Joe Hill memorial concert where Maja Heurling was performing songs from the album Påtår hos Moa Martinson [Refill at Moa Martinson’s], a collaborative work based on the life and work of Moa Martinson, famous for her working-class literature. I loved it. A few days later, I emailed Heurling to tell her a little about Signe Aurell. As a contemporary of Martinson, the parallels were clear, although Aurell was basically unknown in both Sweden and the U.S. compared with Martinson. Heurling, to her credit, responded to the out-of-the-blue email and suggested meeting up to talk. So we did. I sent her Aurell’s book of poetry and talked more about the work I did as a folklorist.

Later, she would say “Det var som att få en skatt i händerna. Jag kände direkt en stark samhörighet med Signe och hennes brinnande sätt att skriva. Hon förtjänade helt enkelt en plats inom svensk lyrik” [“It was like a treasure landed in my lap. I immediately felt a strong connection with Signe and her passionate way of writing. I felt that she deserved recognition within Sweden’s poetic tradition.”] (Kakafon 2019). Together, as we thought through different avenues of potential collaboration, we sought to amplify the story of a young immigrant woman whose story resonated with contemporary issues of immigrant rights, labor rights, and women’s rights. Relying on Aurell’s poetry, we could draw on both Swedish American immigrant and labor poetry traditions along with the Swedish visa tradition. A visa is often characterized as a type of stylistically simple, storytelling folk song (Jonsson 2001 [1974], 5). In this tradition, Aurell’s labor and migrant poems could be put to music and re-presented to help audiences understand migration and labor history from a Swedish American perspective.

In 2018, together with my fellow Wisconsin-based folklorists Anna Rue and Nathan Gibson, we hosted a symposium in Madison that brought together musicians from the Nordic region and Nordic America, including Heurling. Artists, academics, culture workers, and community members discussed Nordic folk music and how and by whom it was being documented, preserved, revitalized, and reimagined on both sides of the Atlantic. Heurling performed a couple of Aurell’s poems as songs for the first time.

That symposium lit a fire. Heurling had already begun putting music to the poems and also teamed up with Ola Sandström, another accomplished musician who had experience putting poetry to music and who had been recognized by Sveriges kompositörer och textförfattare [Sweden’s composers and lyric writers] for his contribution to the Swedish visa tradition (Skap 2017). Together, they put Aurell’s Irrbloss to music, formed a band, and recorded Irrbloss, the album.

With the 2019 release of the album, Aurell’s life, experiences, immigration, and activism were suddenly being discussed in Swedish newspapers and on Swedish radio. Heurling and Sandström, along with Livet Nord and Daniel Wejdin, began performing throughout Sweden.

Their “informance,” 1 a performance that also informs, focuses on telling a complicated story of Swedish immigration and emigration and the challenges faced by working-class women through the experiences of Signe Aurell in her new home. Based on scholarly research, it also contextualizes the experiences of immigrants to the U.S., such as traveling conditions, living conditions, and working conditions.

From left to right: Live Nord, Maja Heurling, Ola Sandström, and Nate Gibson prior to a performance at the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Photo by Marcus Cederström.

Developed almost like a stage play, Irrbloss the informance includes a script, performance attire (all black), a backdrop, and props (like printouts of a 1915 newspaper featuring Aurell’s poetry). Heurling and Sandström also sought the advice of a director. The two had designed similar shows in the past, so they weren’t completely unfamiliar with the process. Heurling previously studied as a drama teacher, working especially with children. Their collective experiences helped shape the show as a work of both art and education. They designed a teacher’s guide about Irrbloss to be used in classrooms in Sweden that featured discussion questions as well as various activities, including a poem-writing exercise to connect with the visa tradition. Supplemental efforts like these, in addition to the informance itself, the album, and its continued life on digital platforms like YouTube, extend the reach of the research far beyond a single dissertation, or even one collaborative informance.

But to boil down an entire life, the complicated history of Swedish migration to the U.S., and issues of labor activism and gender equality into an hour is no small task. Heurling notes that, in some ways, choosing which stories to include was made easier by Aurell’s obscurity. In an interview ethnomusicologist Carrie Danielson and I conducted with her, she explained that they didn’t have too many hard choices to make simply because there was so little known about her (Heurling 2022). My job as a researcher was to fill in those gaps as best I could, to piece together a story of a life lived. Heurling and Sandström used Aurell’s poems and my research to create an easily accessible, moving, and beautiful piece of educational art. The result—a contemporary expression of the visa song tradition and reinterpretation of labor and migration history—is a great example of how collaboration between researchers and artists can lead to rich and meaningful programming.

In describing the informance, Heurling says, “Jag hoppas vi kan förmedla det tidlösa i Signes dikter, det finns så tydliga paralleller till idag, om flykt och kampen om rättvisa. Något som alltid pågått och kommer pågå” [“I hope that we can communicate the timelessness of Signe’s poems, there are such clear parallels to today, about flight and the fight for justice. Something that has always happened and will continue to happen”] (Nilsson 2019). In other words, the history represented both by Aurell’s poetry and the visa tradition is translated to contemporary relevance. This type of informance becomes one obvious way that research can support public programming, amplify the work of artists and musicians, and make direct connections between historical and contemporary issues.

From left to right: Livet Nord, Maja Heurling, Ola Sandström, and Nate Gibson perform at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Photo by Marcus Cederström.

Crossing the Atlantic: Irrbloss in English

First developed in Swedish, the one-hour informance was translated into English for the Irrbloss: Songs from the Poetry of Signe Aurell tour in 2022, which brought Irrbloss back to the U.S. Four songs, originally written in Swedish, were translated into English by Heurling, Anne-Charlotte Harvey, and me. We prepared a handout for audience members with lyrics in Swedish and English. The informance is meant to be beautiful. It is also meant to be emotional and challenging and encourage audience members to reflect on longing and loss, to challenge assumptions about Swedish migration to the U.S., and to educate audience members about the lived experiences of Swedish working-class immigrant women—all through a contemporary approach to the Swedish visa tradition that relies on poetry, written in Swedish but in the U.S., from over 100 years ago.

With the informance ready to go, from September 29 until October 9, 2022, I played the role of roadie for Maja Heurling, Ola Sandström, and Livet Nord—folk musicians from Sweden—and Nate Gibson, an American upright bass player. We drove 1,241 miles over ten days. We visited three states and four cities and the band performed at four different venues. We presented to hundreds of students in four classes at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and one youth group in Minnesota. We debuted six music videos and a full-length set of six songs on YouTube. The band released an English-version EP with four songs based on their full-length record release from back in 2019. We met with professors, museum presidents, nonprofit directors, and radio hosts and had conversations with scores of community members and students. Together, these different modes of performance—CDs (both physical and downloadable), music videos, live concerts, in-class presentations, individual conversations—allowed audiences to interact with Aurell’s poetry in a variety of ways and long after the ephemeral live informances ended. This poetry had nearly been forgotten but represents many experiences of Nordic migration. These experiences challenge the migration histories of the U.S. and Sweden and ask audiences to reflect on their own preconceived notions of historical migration while drawing connections to contemporary migration.

Audience members react differently to the show. In Sweden, the group has performed at cultural centers, libraries, museums, concert venues, and on a host of other stages, including at refugee and new migrant centers. In the 2010s, Sweden saw an influx of refugees and other migrants with over 200,000 refugees coming to the country. In 2016 alone, over 70,000 refugees were granted residency in Sweden. As Danielson writes, this equated to over two percent of the country’s population and Sweden accepted refugees and asylum seekers at one of the highest per capita rates in Europe during 2015 and 2016 (2021, 2–3). Sweden’s longstanding support of humanitarian causes has been eroded, to some extent, by a backlash to migration through increasingly onerous laws and regulations.

At the same time, as Danielson explains, there is a “historical understanding among Swedes that the arts and arts education provide meaningful pathways to global citizenship, community, and selfhood” (2021, 3). In line with this mode of thinking, Heurling and Sandström often performed at refugee and new migrant centers. Heurling and Sandström report having recent immigrants to Sweden come up to them after the show commenting on the echoes of their own migration stories that they heard in Aurell’s songs. One person told Sandström, “Back home I felt happy, but I wasn’t safe. Here I am safe, but I’m not happy.” Heurling notes that these reactions are common: “All the time, people come up to us to share something that is really personal” (Heurling 2022). The contemporary connections were clear in various reviews of the album as well: “Fråga den flykting som korsar ditt spår och du ska med all sannolikhet få höra liknande beskrivningar av längtan till de kända stigarna” [“Ask any refugee that you cross paths with and you’ll almost certainly hear similar stories of longing for familiar paths”] (Östnäs 2019).

In the U.S., people also reported personal reactions, but with a different valence. In an interview with Danielson and me, Heurling said, “The ones I hear are very moved. Very moved. Almost every time there is someone coming up with tears in their eyes” (Heurling 2022). In Minnesota, one person told her, “I’ve been wondering so much about my great-grandmother. She came from Sweden and I’ve been trying to write her story. Now, I’ve got a witness” (Heurling 2022). An audience member in Minneapolis told Heurling about her grandmother, who moved to the U.S. just a few years before Aurell. A few weeks after the show, that same person sent me an email, writing that this project “helped me to make additional connections to the worlds of my immigrant ancestors—especially the women.”2 In Madison, Wisconsin, Heurling reported that a woman in her 70s came to her after the performance ended and said, “Jag grät genom hela konserten. Jag har hela tiden undrat hur det skulle varit om jag åkt tillbaka till Sverige” [”I cried throughout the entire concert. I’ve always wondered what it would have been like if I had moved back to Sweden”].3 Student reactions were more diverse. Some commented on the migration story and contemporary connections, others spoke to the sustainability of traditions, but many focused on the performative experience itself. One student mentioned how they were brought to tears, moved not just by the content and music, but by the fact that it was their first in-person musical experience since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

We see a clear distinction here based on the makeup of the audience. In Sweden, reactions are sometimes immediate, speaking to the lived migration experiences of audience members who have immigrated to Sweden in the last few years. In the U.S., where the band performed mainly for crowds who had not themselves migrated, these reactions often related to their ethnic and family heritage. These two reactions, slightly different even if both highlight Irrbloss’s emotive power, speak to the ties between historical and contemporary migration and the importance of public programming like this one. In fact, the strong reactions are part of the point, as the informance sought to make clear that the experiences of Swedish immigrants to the U.S. 100 years ago are not so different, unfortunately, from the experiences of migrants today.

Traveling Informances

These projects are not easy. This multiyear, multiperson, multimodal effort to enhance and complicate our understanding of Swedish migration and bring academic research to the public sphere by coordinating with community partners in several cities, had several challenges. For one thing, we planned this program three separate times. Twice we canceled the tour because of the Covid-19 pandemic. There were visa issues. There were the standard bureaucratic challenges of working at a large institution. There were financial challenges, as costs increased significantly over the three years.

No matter the delay, projects like this are expensive. There’s no way around that. Of course, part of why it was so expensive was because it was international. The tour itself cost just over $22,000. As part of a large grant project at UW–Madison, we paid for nearly everything: all travel costs, lodging, per diem, and a generous honorarium. We did this to make it easier for our three partner institutions to organize an event that was not guaranteed to draw a large crowd. And it worked. Contributing food or lodging or a small honorarium, rather than an entire tour, helped mitigate potential losses and redistributed the funds that we had to benefit audience members and our community partners by helping them to expand their programming.

And people loved it. At the same time, our partners were wary. They expressed two main concerns about the event:

- People aren’t coming to cultural events or performances as much as they used to before the pandemic began.

- People are especially not coming to cultural events or performances by people or groups that they do not know or have not heard of.

This was a risk we were willing to take. And it was a risk that we could afford to take because of the large grant we have to fund these types of programs. To be successful—and ethical and representative—projects like this should be artist-driven and community-driven, which helps to ensure, but cannot guarantee, relevance and interest and representation. But artists and audiences do not always overlap. In this case, we had very strong artist buy-in. However, the Swedish visa tradition, not to mention traditions of migrant and labor poetry, is not well known in the Swedish American community. One of our community partners told me they had no problem filling a room when a Swedish nyckelharpa player came to town because so many people in the Swedish American community are familiar with the instrument (a traditional keyed string instrument). But labor songs in the visa tradition? That was a harder sell. In the end, though, thanks to tireless outreach and educational efforts, the group performed in front of over 200 people and presented to nearly 500 college students.

Our work in the classroom was an important aspect of that success. In speaking with so many different students, we tailored our presentations. In an Intro to World Music course, students were asked to read articles about Aurell and Nordic and Nordic American folk music in advance of the visit. In addition, they were provided a set list and English translations, and, finally, they received links to the music videos we had produced prior to the tour. Doing so ensured a richer discussion and allowed us to talk more deeply, specifically, about the Swedish visa tradition. In an Intro to Folklore course, students were similarly provided some readings about Aurell and the music videos, but here we focused more on the public folklore aspect of the project to meet the learning objectives of a specific unit. In a class on music learning and teaching, Heurling, Sandström, and Nord, all of whom have extensive teaching experiences, discussed the pedagogy of teaching folk music, as well as the challenges of setting poetry to music. By tailoring our presentations and discussions, we were able to meet the learning objectives of the host instructors and make for a more meaningful student experience than a simple guest lecture. While an imperfect measure, the number of students who stayed after class to speak directly with Heurling, Sandström, and Nord indicated a connection with both the music and the context that we presented.

From left to right: Ola Sandström, Maja Heurling, and Livet Nord during a class visit at the School of Music at UW–Madison. Photo by Marcus Cederström.

Maja Heurling authored a curriculum guide in Swedish, IRRBLOSS Lärarhandledning. Find suggestions for discussion questions, prompts, activities, as well as a copy of one of Aurell’s poems for classroom prep. [Note: No translated guide available, eds.]

Projects like this one can be altered to meet the needs and wants of the community or classroom. By focusing on the connection to community and introducing a nuanced understanding of history and heritage, educators can lift up various aspects of traditional arts to meet their learning objectives. Naturally, doing so means that each iteration of such a multi-audience experience may differ based on community needs, funding availability, and classroom learning objectives.

The success of this project is a reminder of the role that public folklorists can play in co-creating programming. We had engaged, highly motivated artists. We had several local community partners and audience members connected to the stories they carry in themselves, to their families’ migrant histories, to contemporary folk traditions. While the band and Signe Aurell’s work may have been unknown to audiences prior to the tour, by hosting such an event at several venues, we lifted up undertold immigration stories and, specifically, stories with clear contemporary connections. While the specifics depend on individual situations, partnerships between public folklorists, traditional artists, and educators that combine traditional arts with deeply researched historical and contemporary issues regularly produce similar success stories. This project reiterated how good public work is strengthened by good research and that good research is strengthened by good public work (Frandy and Cederström 2022, 8). That’s one crucial place where folklorists have a role to play in educating audiences—through the contextualization and amplification of various artists. Living and dead.

Irrbloss was Heurling and Sandström’s show. But with an assist from me and the team at UW–Madison, especially Anna Rue, Carrie Danielson, and Erin Teksten from the Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures and Nate Gibson from the Mills Music Library, we made sure that this project was easily accessible while being based on deeply researched scholarship. This public production helped us amplify both Signe Aurell’s voice from 100 years ago and the work of musicians in the Swedish visa tradition. Because of the public aspect, a much wider audience has had their assumptions about Swedish migration challenged and, in turn, learned about Signe Aurell and the understudied history of Swedish immigrant women.

Reverberations

In an interview in 2022, Heurling said, “It’s not about me. It’s about someone else and it’s about leaving something behind, leaving something behind for the future, maybe. I feel my mission is not completed because I want these songs to be in songbooks. I really want that. I’m going to make that happen. Somehow. Because there are no women in the songbooks, in the old songbooks, almost no women. There should be” (Heurling 2022).

Seven months later, in May of 2023, I received an email from Heurling in which she wrote, “För övrigt kan vi berätta att ‘Till mitt hem’ har blivit utvald att vara med i en visbok i Svenska Akademiens klassikerserie! Den kommer ut nästa år. Vi är så otroligt glada över detta.” [“By the way, we can tell you that ‘Till mitt hem’ (To my home) has been chosen for inclusion in a visa book from the Swedish Academy’s classics series. It will be published next year. We are so unbelievably happy about this.”].4

As Signe Aurell’s work continues to reverberate on both sides of the Atlantic, it is being taken up, performed, recited, and used by a variety of people and artists in different contexts. Covers of Heurling’s version of Aurell’s poems can already be found online. Joe Alfano, a member of the Swedish American folk group Tjärnblom in Minneapolis, has used Signe Aurell’s stories in his own informances, including one performed at Story Swap, a collaboration between the American Swedish Institute and Minneapolis Public Schools that partners immigrant high school students with Swedish American elders to build relationships and share their cultures across generations—another example of how a project like this can be tailored to meet the needs of specific communities and classrooms.

The Irrbloss story is about history, of course. But it is also about heritage and how we relate to it; about the continuation of a song tradition; about the labor movement and women’s place in it; and, importantly, about migration then and now. As I’ve written elsewhere, “…heritage is created by community members through their interpretation of history, memory, and lived experiences and can tell us what a community values, what a community hopes to preserve, and how a community hopes to present itself to the future” (Cederström 2018, 396). Irrbloss sought to amplify a specific tradition, while preserving and presenting the undertold histories of Swedish immigrant women for future generations. In doing so, our partners and our audiences demonstrated how they value these stories now and how they aim to reclaim them, relearn them, and re-present them in the future. As a public folklore project, Irrbloss brings a variety of public programs and productions to audiences in various contexts, working to educate and challenge these audiences to continue to re-think and re-present Nordic and Nordic American immigrant history as we all work to amplify underrepresented histories.

Marcus Cederström is a public folklorist working in the Department of German, Nordic, and Slavic at UW–Madison as the community curator of Nordic American folklore for the “Sustaining Scandinavian Folk Arts in the Upper Midwest” project. His research interests include immigration to the United States, Nordic and Nordic American folklife, Indigenous studies, and sustainability. Cederström teaches folklore courses, conducts fieldwork with Nordic American and Indigenous communities throughout the Upper Midwest, and works with a wonderful team to create public programming and productions supporting Nordic, Nordic American, and Indigenous folk arts.

Endnotes

1 A portmanteau of the words “inform” and “performance,” an informance is an educational performance. In use since around the 1970s, music educators and other performers have used this style of presentation to perform and educate while on stage. Informances, as Mary Pautz uses the term, can also inform audiences of student learning in elementary school music programs, for example (2010, 20).

2 Kay Myhrman-Toso, email message to author, October 20, 2022.

3 Maja Heurling, ”Svenskt poesiprojekt mottogs med starka känslor i USA” message to author, October 21, 2022.

4 Maja Heurling, email message to author, May 10, 2023.

Related Resources and URLs

Heurling, Maja, IRRBLOSS Lärarhandledning. Curriculum Guide in Swedish https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Heurling-Maja-IRRBLOSS-Lararhandledning.pdf

CSUMC Irrbloss Playlist on YouTube https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLwChImUyWQ_o1n8kmikUzcTwpKVfPDPg0&feature=shared

Maja Heurling Irrbloss Trailer https://youtu.be/ikeySZvfW4g?feature=shared

Spotify Irrbloss https://open.spotify.com/album/3zDLluunVIMDnNUqkT8TRO?si=kd9H09-0TX2o03BoiUlxGw

Spotify Irrbloss English EP https://open.spotify.com/album/1fII90Pk7bVO1t5BQJVrKJ?si=LYSWsCO8R5mccPvdjscqPQ

Maja Heurling’s Irrbloss website https://www.majaheurling.se/signe-aurell-irrbloss

Works Cited

Attebery, Jennifer Eastman. 2023. As Legend Has It: History, Heritage, and the Construction of Swedish American Identity. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bokstugan. 1920. Bokstugan, 1.8:17.

—. 1921. Bokstugan, 2.16: 26.

Cederström, B. Marcus. 2016a. Don’t Mourn, Educate: Signe Aurell and the Swedish-American Labor Press. Swedish American Historical Quarterly. 67.2: 71–89.

—. 2016b. In Search of Signe: The Life and Times of a Swedish Immigrant. PhD Dissertation. University of Wisconsin–Madison.

—. 2018 “Everyone Can Come and Remember”: History and Heritage at the Ulen Museum. Scandinavian Studies. 90.3: 376–402.

Danielson, Carrie Ann. 2021. The Word “Refugees” Will Always Be Stuck to Us: Music, Children, and Postmigration Experiences at the Simrishamn Kulturskola in Sweden. PhD Dissertation. Florida State University.

Engdahl, Walfrid. 1961. Signe Aurell. Kulturarvet. 4.1: 8–9.

Frandy, Tim and B. Marcus Cederström. 2022. Introduction. In Culture Work: Folklore for the Public Good, eds. Tim Frandy and B. Marcus Cederström. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 3–10.

Heurling, Maja. 2022. Interview with Marcus Cederström and Carrie Danielson. October 3. Madison, Wisconsin.

Jonsson, Bengt R. 2001 [1974]. Visa och folkvisa: Några terminologiska skisser. Noterat 9. Stockholm: Svenskt visarkiv.

Kakafon. 2019. Irrbloss – Tonsatta dikter av Signe Aurell • Maja Heurling & Ola Sandström. Kakafon. October 18, https://kakafon.com/hem-katalog/irrbloss-maja-heurling-och-ola-sandstr%C3%B6m-kakaep001-46085088.

Lintelman, Joy K. 2009. I Go to America: Swedish American Women and the Life of Mina Anderson. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Nilsson, Lisa. 2019. Bortglömd diktsamling av Signe Aurell blir musik: ”Otroligt rytmiskt.” SVT. April 15, https://www.svt.se/kultur/bortglomd-diktsamling-av-signe-aurell-blir-musik-otroligt-rytmiska.

Pautz, Mary. 2010. Both Performance and Informance: Not “Either–Or” in Elementary General Music. General Music Today. 23.3: 20–6.

Skap. 2017. Skap delar ut årets musikpriser. Skap. October 2, https://skap.se/blog/2017/10/02/skap-delar-ut-arets-musikpriser.

Wyman, Mark. 1993. “No Longer Freedom’s Land”: Scandinavians Return from America, 1900-1930. In Norwegian-American Essays, eds. Knut Djupedal, Øyvind T. Gulliksen, Ingeborg R. Kongslien, David C. Mauk, Hans Storhaug, and Dina Tolfsby. Oslo: NAHA-Norway, 9–96.

Östnäs, Magnus. 2019. Tonsatt poesi Maja Heurling & Ola Sandström Irrbloss. Lira Musikmagasin, November 22, https://www.lira.se/skivrecension/irrbloss.