Figure 1. New York Times, August 11, 1985.

So, during the project, my role was really to just be a helper and to also do some taping and talking, interviewing the adults of that generation, my parents, uncles, and the leaders in the community. And I think the greatest thing was that, for me, is to see and to get from their perspective, how they felt coming to America and living in a different culture, a different environment, a different society, where, you know, there’s the language barrier and trying to understand, trying to find out, figure out life, and also thinking about their life back in Laos.

Interview with Phua Xiong, 2021.

Scene One: A Collective Viewing of Six Hours of Video Footage Documenting Hmong Community Culture. West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1984)

Setting: A large conference room at International House in West Philadelphia in 1984. Almost 100 Hmong community leaders and members gathered at International House near the University of Pennsylvania to view a compilation of six hours of video footage documenting the life of Philadelphia’s Hmong community. The Folklife Center of International House hosted this open forum and invited Philadelphia’s Hmong community to review and comment on these scenes recorded by Hmong Community Folklife & Documentation Project participants. (See Appendix for a list of organizations and people critical to this project.)

This innovative multi-year collaboration trained and engaged seven young Hmong as they documented their community through interviews, photographs, sound, and video recordings, supported by non-Hmong cultural professionals. After two years of planning and nine months of recording and transcribing interviews, developing and printing photographs, shooting and editing video, and negotiating with Hmong elders the protocols of who and what in the community to document, all done collaboratively between the Hmong project members and the folklorists and anthropologists, a series of products were almost ready to share with the community and beyond, hence the viewing session.

Figure 2. Still from Years Away from Laos: The Hmong in Philadelphia, 1985. Other project elements are on the Library of Congress website at https://lccn.loc.gov/2015655510.

This group viewing and listening event in the fall of 1984 was a form of archival engagement and meaning making, and an important moment for members of the Hmong community in Philadelphia. Later, comprehensive archival materials from this project were assembled and shared with the Hmong United Association of Pennsylvania, then based in West Philadelphia, and also housed at The Folklife Center of International House.

Figure 3. Photograph of the Hmong Community Folklife & Documentation Project Team. Philadelphia, 1985. Photo Credit: Barry Dornfeld.

We structure this narrative around three representative “scenes,” loosely defined, mental milestones in the life of a community’s history and in the evolution of the work of folklorists and media makers connected to this community at various points. These scenes are chosen from a wider pool of other available interactions and events, moments of collaboration and support between members of the Hmong community, non-Hmong cultural institutions, and interested outsiders. In telling this story, we reflect on and hope to learn from these experiences and relationships to better understand the power of a living cultural archive in sustaining culture and community. This exploration aims to examine how a multigenerational Hmong family worked with other community members and with cultural and media collaborators to sustain cultural memory through formal and informal representations, stories, and events and how the traces of these events have found themselves living on in archival form, like the narratives that Hmong paj ntaub story cloths represent of Hmong refugees escaping the Vietnam War and its aftermath, migrating from refugee camps in Laos eventually to arrive in the United States, and making lives here over the past 45 years.

Figure 4. Xia Kao Xiong, his son, and his grandchildren, Philadelphia. Still from Years Away from Laos: The Hmong in Philadelphia, 1985.

Examining one Hmong family’s “archive” as a living, multimodal cultural practice challenges conventional paradigms that view archives as formal repositories of cultural artifacts, cataloged, organized, and kept apart. We want to offer that seeing “archiving” in all its dimensions–soliciting and collecting material from others, viewing and reviewing recordings and images, editing and adding, narrating, remembering and forgetting–as a living process versus a postmortem undertaking–opens up many possibilities and challenges for the community members and cultural workers committed to their sustainability and for the rich set of cultural materials they engage. In this sense, the archive is a catalyst for action, not just a container holding the traces of earlier actions.

As far as the project with folklife is very fresh for us at the time, because we just came here not too long ago. Thinking back, I wish we had the project again now, because now I have more ideas about what to do, what not to do. But looking back at the time we were learning at the same time, not just doing the project, but learning at the same time, talking to the elders in the community. Sometimes they have their own way of saying or doing things. But then, like I said, we did the project, and we were learning at the same time, culture-wise. We learned through talking to all the people, and we learned how to document via an interview. As I grew up, I thought if I had more time to learn more, it would be great to continue the culture of Hmong people here in the Hmong community.

Interview with Chakarin Sirirathasuk, 2021.

“Archives” as Collaborative Community History

Others have probed the idea of the cultural archive and the traditional practices behind archiving in cultural documentary work. Anthony Seeger, for instance, observed that “archives, technology, communities, and sustainability are all complex and heatedly debated concepts” (Seeger 2022, 1). The archives discussed here are seen as vital, underbounded, and complicated by family and clan group identities. Seeger asked, “What is an archive?” and included a definition from the Oxford English Dictionary: “[a] place in which public records or other important historic documents are kept” (OED, 435). We would broaden the idea of the archive, as others have, beyond formal records and historic documents and include other forms and formats—a book of recipes as an archive of its own within the larger collection, an assemblage of paj ntaub story cloths sewn by community members that tell the story of Hmong migration to the U.S., a box of pepper plant seeds passed down and cultivated over many years, a family Facebook page carefully added to, songs composed and sung, and so on.

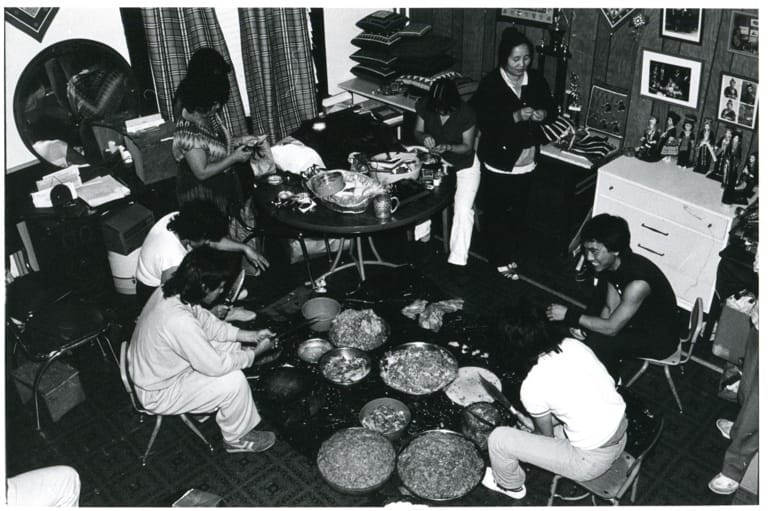

Figure 5. Photograph of preparation for Hmong New Year, Philadelphia, 1984. Hmong Community Folklife & Documentation Project. Photo Credit: Chakarin Sirirathasuk.

Scene Two: A Hmong Home as a Living Incubator and Museum.

Upper Darby near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1979 to the Present)

Setting: The family home of Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun, Hmong artist, community activist, and cultural entrepreneur, continues to be an ongoing site of creativity, learning, and cultural sustainability. Born in Laos, Pang fled to a Thai refugee camp in 1976 and moved to Philadelphia in 1979. Best known for mastery of the Hmong embroidery technique paj ntaub, or “story cloth,” in addition to her own family folk art traditions including singing, storytelling, music making, dance, Pang was a devoted teacher of Hmong traditions. She shared her cultural knowledge twice at the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife in 1980 and 1986 and subsequently exhibited her work in municipal, regional, state, national, and international settings. In addition, Pang received awards from the Pew Fellowship in the Arts and the Social Science Research Council.

Figure 6. Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun teaching paj ntaub during a Folk Arts Apprenticeship, Upper Darby, PA, 1984. Hmong Community Folklife & Documentation Project. Photo Credit: Mai Xiong.

Pang passed away on December 22, 2020, at 76. Her family home in Upper Darby has been a “living museum” and “community anchor” for many years. A gathering place for Hmong and non-Hmong friends to convene, eat traditional Hmong food, view and purchase beautiful tapestries, and share stories, her home was and is a public place of cultural engagement for several decades, alongside being a private family home.1

Domestic spaces, material culture objects, historical narratives, and social media collections also function as parallel archival repositories, sustaining culture despite gaps in community and institutional support and attention, spreading cultural resources beyond place, people, and time. Like the Sirirathasuk house in Upper Darby where several generations of the family lived (pictured earlier), these spaces offer structures of participation and re-creation, as images, sounds, text, recipes, spices, and fabrics get repurposed, renamed, and reshelved in closets and kitchen pantries, and as people move across the country, have children and raise families, navigate work and careers, come back to visit, and pass on.

While non-Hmong ethnographers, folklorists, and media makers have added to and helped sustain this living archive, family members and friends have done much more in sustained if episodic ways. Ongoing celebrations have been documented; dance traditions reenacted; story cloths sewn, imported, and sold. Food traditions are sustained, and elders continue to be commemorated in death. Compared with Hmong populations in other cities (Minneapolis and Fresno, for instance), the Hmong community in Philadelphia is small, and now mostly woven into the cosmopolitan lifeways of urban America. Fortunately, Philadelphia’s Hmong inculcated values and practices that take responsibility for history and memory.

As a parent, I’m trying to pass on the tradition that Mom taught me. And I’ve always tried to tell my wife, Dannelle, that we need to do this for the kids, so that they don’t forget what Grandma was all about and how famous she was in paj ntaub and in the folklife industry, in just about everything that she did. You know, she’s one famous person. So, I want to make sure that the grandchildren, you know, don’t forget who Pang Xiong was.

Interview with Chakawarn Sirirathasuk, 2021.

Scene Three: A Celebration of Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun’s Life.

Kimberton, Pennsylvania (2022)

Setting: Hundreds of family members and friends gather in a firehall in rural Kimberton, Pennsylvania, to celebrate Pang’s life, which ended too soon because of complications from Covid-19. The gathering includes traditional Hmong food, family narratives, performances of dance and singing, talks by colleagues and friends, and the affirmation and deepening of informal social connections.

Figure 7. Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun Memorial Invitation, 2022.

Photo courtesy of Sirirathasuk Family.

In the entrance to the long hall, there is an impressive display of paj ntaub story cloth tapestries, family photos, and streaming video, including the Hmong Project documentary mentioned earlier, playing on a monitor in the back of the room.

Figure 8. Photo of Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun at a New Jersey festival. Photo courtesy of Sirirathasuk Family.

This archive was brought to life at this moment and to this space to help metaphorically send Pang Xiong off to the next world and simultaneously keep her memory fresh and relevant. The celebration, a remarkably rich gathering and cultural event, full of performances, testimonials, and other, more informal, opportunities to (re)connect people with living traditions, centered Pang’s work and life in this civic space and in the cultural history of Philadelphia’s Hmong community. Here the community archive came full circle. Pang was one of the driving forces to initiate this stream of cultural activity early in her stay in the U.S. The artistic work she helped cultivate was taken up by her children and their children. The memorial event gave hope to those who wonder how it will be sustained as time moves on, and how it may evolve and change.

Mom’s memories for me are very endearing, because, like I said, I came to live with her in 2005, and I’ve lived with her since. There were many nights where I would be in the kitchen with her, helping her, and then we’d be moving on into the dining room, where she has all her crafts and where she tells the stories. I often tell Chakawarn that it isn’t when Mom is lecturing us, when she is instructing us, that is the person that they needed to listen to. It was that person that, later at night, as she tells the stories of who she really is and what being a Hmong woman meant to her and how her life was as a Hmong woman.

Interview with Dannelle Sirirathasuk, 2021.

We might take a warning from this archival narrative as well. As we were gearing up for this Commemoration, Hmong and non-Hmong family, community, and project participants began to search for the original materials in The Folklife Center of International House’s archive—hundreds of photographs and negatives, scores of oral history recordings and transcriptions, and the original video camera reels and outtakes. When The Folklife Center closed in 2007, Center leadership arranged for this collection to be housed in a new off-site location. Where had the materials been relocated? Project leadership reached out to Philadelphia’s Hmong United Association of Pennsylvania, which stated that they no longer maintained or held their collection, due to issues with dated technologies. Was this material, a rich portrait of a refugee community here in the U.S., lost forever?

Months later, Carole Boughter, the former Director of The Folklife Center (and co-author of this article), learned from the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress that boxes of Hmong project photographs, recordings, videotapes, and transcriptions had been delivered there and were beginning to be digitized. The Philadelphia Folklore Project, which picked up support for and collaborated with Pang and other Hmong artists through the early 2000’s, has begun a process recently of moving its archive to the Philadelphia Folklore Project Archive, Urban Archives, Special Collections Research Library, Temple University. Additional chapters in the life of this cultural archive have been given root, but only through the work of individuals and institutions who cared enough to make this happen.

Conclusion: Toward a New Archival Framework and a Sustainable Hmong Legacy

As Seeger wrote:

Archives do not sustain traditions. People sustain traditions. Sometimes they use archival recordings. People often create new art forms from fragments of other art forms. A fragmentary recording, along with photographs, written documents, and community memories, can provide individuals and groups with an inspiring vision of a total performance. A hint of a performance can encourage renewals; a spark from a fire can start conflagrations; a bit of shell can recall the egg. Even today, the fragments in archives, in the hands of a set of motivated and innovative individuals and communities, can help to sustain traditions and (re)create whole performances. A few decades from now, the materials assembled in the multiverse of archives being created today may provide even better resources for individuals and communities, as long as they haven’t been lost. Increased recognition of the importance of performances for cultural diversity and self-determination may help to shape a musical, archival, and sustainable future that is different from our past. But achieving it will require determination, reflection, collaboration, hard work, emotional commitment, and thoughtful reflection. (Seeger 2022, 17)

Building upon Seeger’s perspective as well as the work of others on indigenous and collaborative media making (Ginsburg 1991 and many others), we propose an “activated archives” model that centers on lived experience; media and materials in multiple, evolving forms broadly understood; artifacts of many sorts; and informal education, nurtured and kept alive, therefore remaining relevant. In this case, the Philadelphia Hmong “archive” has been tended, like Pang’s backyard gardens, for several generations. When activated and reactivated in this way, archival material can become a resource for collaborative remembering when reintegrated into contemporary communal dialogues and public forums. This notion of an activated archive is similar to important work done at other activated archives like The Community Archiving Workshop, the Indigenous Archives Collective in Australia, ENTRE Film Center in Texas, and Remembering Black Dallas.

Consequently, this multidimensional archive is not just a record of a life and lives lived and living, but a critical dimension of the experiences and narratives that make lives rich and sustain meaning. It is a living archive in multiple forms that has enhanced the experience of Hmong and non-Hmong, embedded in learning, teaching, memory, and sustaining culture. Like the lives of this family and others, it is complex, multidimensional, geographically spread, economically generative, and at times precarious. It has been tended by many, has grown, become concrete yet ephemeral, digital and analog; hopefully, it will remain vital for years to come.

Figure 9. In a 2006 photograph, Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun and husband Somboun Sikoun hold a collaborative paj ntaub (story cloth) by artists Mee Yang, Pang, and others. Photo courtesy of Philadelphia Folklore Project.

As we write, pronouncements that raise additional existential concerns about the longevity and precariousness of the nation’s archives and records arrive daily. The National Endowments’ (Arts

and Humanities) budgets are being drastically cut, the nation’s Librarian of Congress was fired, research funding for the social sciences has been substantially reduced, and museums are being attacked for their curatorial strategies. Knowledgeable and skilled staff are leaving these agencies. We can only speculate about the long-term impact of these unprecedented, politically motivated attacks on the organizational archives of cultural communities. Even worse, immigrant communities themselves are being scapegoated, denounced, and having their members deported, delivering additional shocks to our cultural landscape. When communities activate their archives, as the Philadelphia Hmong community has, with or without the collaboration of individuals or organizations, those archives can be resilient in the face of attack and diminution. The Philadelphia Hmong “archive,” as this story brings to life, has vacillated between moments of strength and moments of precarity, moments of more or less support, raising the stakes for how we can contribute to its growth and sustenance in these turbulent times.

Barry Dornfeld is a Principal at CFAR, a management consulting firm in Philadelphia, a documentary filmmaker, a media researcher, and an educator. He co-authored The Moment You Can’t Ignore: When Big Trouble Leads to a Great Future, with Mal O’Connor (Public Affairs 2014). He has taught at New York University and chaired the Communication Department at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia and has a PhD from the Annenberg School for Communication and a BA in Anthropology from Tufts University.

Carole Boughter is a nonprofit leader and cultural advocate with decades of work across Philadelphia’s arts, education, philanthropic, and community-based sectors. She has held leadership roles in development, mental health, and philanthropy. Her academic background in social work, psychoanalysis, and the arts has shaped a career rooted in equity, collaboration, and lasting community impact. She has an MSS/MLSP from Bryn Mawr College.

Endnotes

1See the program that City Lore in New York City has developed around the concept of Community Anchors, which clearly has resonances here with the concept as we are applying it. See their report at https://citylore.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/COMMUNITY-ANCHORS-Final-Final.pdf

Works Cited

Boughter, Carole and Barry Dornfeld, dirs. 1985. Years Away from Laos: The Hmong in Philadelphia. Hmong Community Folklife & Documentation Project, 25 min., color, stream at https://vimeo.com/628578784

Garfinkel, Molly. 2016. Community Anchors: Sustaining Religious Institutions, Social Clubs, and Small Businesses That Serve as Cultural Centers for Their Communities. City Lore. https://citylore.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/COMMUNITY-ANCHORS-Final-Final.pdf

Ginsburg, Faye. 1991. Indigenous Media: Faustian Contract or Global Village? Cultural Anthropology. 6:92-112.

Oxford English Dictionary. 1971. Compact edition. 1:435. Oxford University Press.

Seeger, Anthony. 2022. Archives, Technology, Communities, and Sustainability: Overcoming the Tragedy of Humpty Dumpty. In Music, Communities, Sustainability: Developing Policies and Practices, eds. Huib Schippers and Anthony Seeger. New York: Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197609101.001.0001

URLs

Years Away from Laos: The Hmong in Philadelphia https://vimeo.com/628578784

Project elements in the Library of Congress https://lccn.loc.gov/2015655510

Philadelphia Folklore Project https://folkloreproject.org

The Community Archiving Workshop https://communityarchiving.org

The Indigenous Archives Collective https://indigenousarchives.net

ENTRE Film Center https://www.entrefilmcenter.org

Remembering Black Dallas https://rememberingblackdallas.org

Appendix:

Hmong Community Folklife & Documentation Project Participants/Funders

Carole Boughter, Director of The Folklife Center of International House/Project Director

Ellen McHale, Assistant Director of The Folklife Center of International House

Chao Song, Community Coordinator

Barry Dornfeld, Media Coordinator

Mal O’Connor, Project Folklorist

Sally Peterson, Project Folklorist

Margaret A. Mills, Project Consultant

Yer Hang

Bee Lo

Moua Lo

Hang Sai

Chakarin Sirirathasuk

Mai Xiong

Phua Xiong

Philadelphia’s Hmong Community

CIGNA Foundation

National Endowment for the Arts – Folk and Traditional Arts Program

Pennsylvania Council on the Arts

The Folklife Center of International House of Philadelphia

The Sun Company

Participants/Funders: American Folklore Society’s 2021 Annual Meeting-Honoring Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun (1944-2020): Keeper of Hmong Culture and Community Activist

Carole Boughter

Barry Dornfeld

Sally Peterson

Mal O’Connor

Bonnie O’Connor

Chakarin Sirirathasuk

Chakawarn Sirirathasuk

Dannelle Sirirathasuk

Mai Xiong

Phua Xiong

Selena Morales

Emily Socolov

Naomi Sturm-Wijesinghe

American Folklore Society

Philadelphia Folklore Project

The Folklife Center of International House of Philadelphia

Participants/Funders: 2022 A Celebration of Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun

The Sirirathasuk-Sikoun Family

Chakawarn Sirirathasuk

Dannelle Sirirathasuk

Carole Boughter

Barry Dornfeld

Naomi Sturm-Wijesinghe

Chakarin Sirirathasuk

PECO

Philadelphia Folklore Project