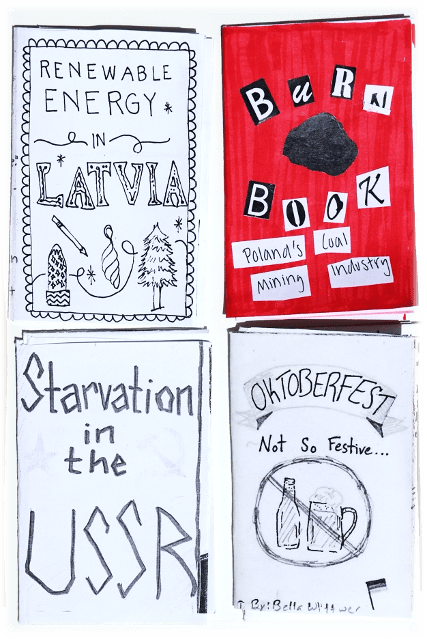

- A selection of zines made by students in GNS 210.

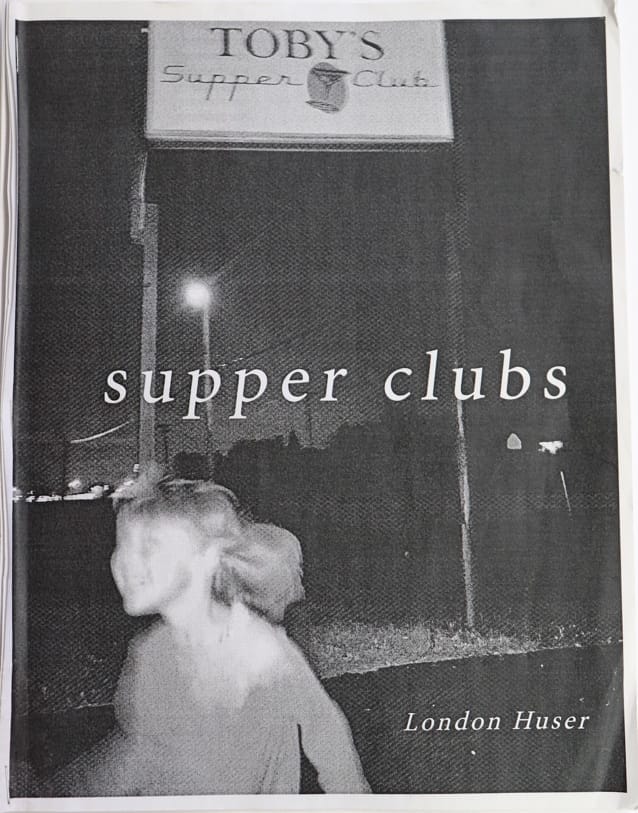

- The front cover of a zine created by London Huser, an MFA graduate student at UW-Madison. Originally from Oklahoma, Huser creates art that explores themes of home, mass production, foodways, regionalism, and more. Her zine for the 2024 Folklore 540 course focused on supper clubs, a distinctive local establishment that has become a symbol of the social fabric and foodways of Wisconsin.

Sarah Kuhn, professor emerita at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, notes that higher education has fallen into a trap of misconceived expectations, namely that students should be sitting passively in a lecture hall, taking occasional notes, learning facts, and quickly understanding abstract concepts. Instead, Kuhn advocates for “learning with things,” challenging this received model of inactive learning by focusing on embodied learning—the knowledge that “our hands, our bodies, our sense of ourselves in space and in motion, all play an important and inadequately understood role not only in our learning, but also in our thinking” (2021, 4-5). A group of instructors at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, including the authors, have become increasingly invested in integrating hands-on learning experiences in the college classroom. As Kuhn argues, embodied learning can combat the common misconception that “Learning takes place inside our heads, so the rest of our body should remain still except to take notes” (2021, 4).

Drawing inspiration from Kuhn, the author of Transforming Learning Through Tangible Instruction: The Case for Thinking With Things, we have worked to put things in the hands of our students. Kuhn, in laying out her case for thinking with things notes that “by recognizing and supporting the embodied learner, we can abandon the sensory deprivation classroom and create learning environments that are enabling rather than disabling” (183). Kuhn argues convincingly that higher education’s overreliance on lectures and textbooks fails to identify creative thinkers and instead caters to those who are most able to withstand a rather unnatural educational environment. In response, we have begun engaging with hands-on workshops in class (pysanky egg painting, butterknife carving, tea-making, and folk dancing, to name a few) and have created assignments that encourage and even require students to work with their hands.

We have found that hands-on activities and workshops, using a variety of embodied teaching techniques, promote student learning and creative thinking. We present below a zine project as a model to bring embodied learning into the classroom. Zines are small circulation, independently created, self-published works of texts and/or images. Often they are photocopied in runs of less than 1,000, sometimes even less than 100 (Matthay 2019). Generally, zines are noncommercial and distributed through unofficial channels. They cover a wide range of topics, expressing the diverse interests of their creators. Zines are not just physical objects but often also represent a specific culture (see, for example, Bobrow 2025, Creasap 2014, Matthay 2019, Piepmeier 2008, Scheper 2023, Wan 1999). Michelle Kempson writes that while zines are often positioned as forms of narrative resistance to dominant discourses, they can also be viewed as a way to “communicate a version of the self” (2015, 460). Zines as self-expression have taken many different forms. Historically, zines have been produced since the 1920s and are often associated with science fiction fan communities, punk subcultures, and feminist movements like Riot Grrrl (Matthay 2019; Wan 1999, 15). They have long served as forms of informal and artistic communication in small groups that demonstrate both dynamic and conservative aspects, features that clearly identify them as a form of folklore (Ben-Amos 1971, 13; Toelken 1996, 39–40). Today, zines cover an increasingly wide array of topics and communicate ideas and other abstract concepts as an informal and creative multimodal storytelling form. Zines are especially attractive now as informal, non-institutional ways to communicate and educate, during a time when government entities and other institutions are actively erasing history and evidence of vulnerable communities all around us.

As folklorists who teach at UW–Madison, we asked our students to create their own zines as a form of multimodal storytelling that incorporates various forms of traditional knowledge to educate diverse audiences. In the folklore classroom, zines allow students to engage with and create a specific cultural artifact. Students are participating in a folk art (albeit one that is facilitated in the college classroom) and are reminded that they are active participants in various forms of folklife outside the classroom. Through ethnographic fieldwork or primary- and secondary-source research, students also examine issues relevant to their lives and the course content.

As Evan Bobrow writes, “In this age where you can publish whatever you want in an instant for the world to see, the decision to make a physical zine becomes a radical act. It is a call for connection, it satisfies an urge for thoughts to be made tangible” (2025). Making those thoughts tangible requires a different level of hands-on work than standard college-level research papers and asks the students to think creatively and concretely about multimodal forms of storytelling. The zine project is one way to make complex and abstract ideas accessible while encouraging students to work directly with their hands—which engages their brains in different and more effective ways than making them read or write another paper. We are not the first to use zines in the classroom and do not want to claim originality in the basic idea (see Bobrow 2025, Creasap 2014, Scheper 2023, Wan 1999), but as implementers in a folklore setting, we want to promote and encourage them as one method of folk art creation and as an example of embodied learning.

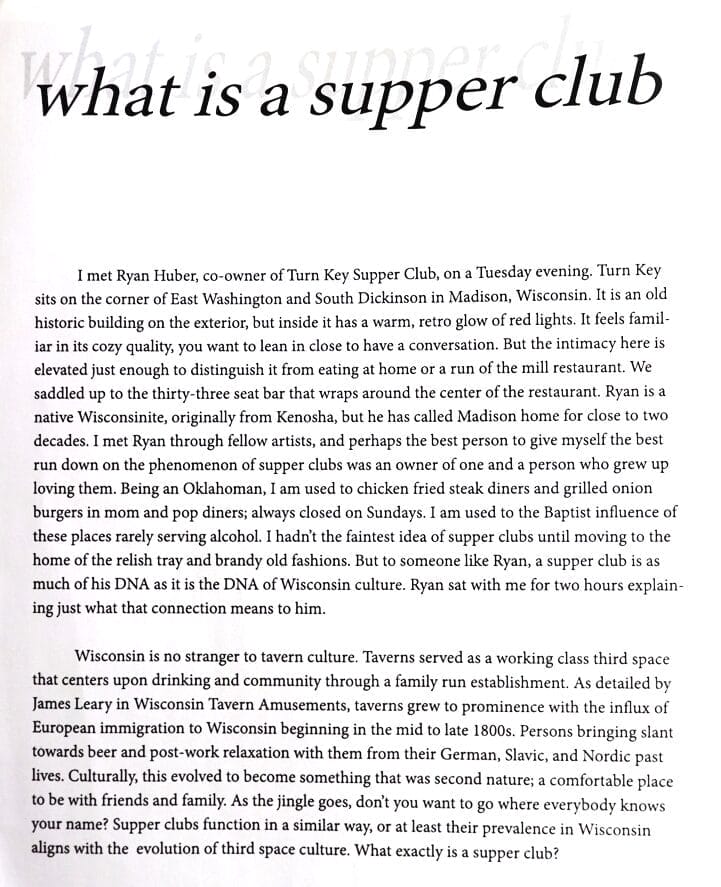

- 1-2 of a zine created by MFA student London Huser in 2024 for Folklore 540: Local Culture and Identities of the Upper Midwest. Huser dedicated her zine to exploring the cultural significance of supper clubs in Wisconsin through an interview she conducted with the owner of a local supper club.

Zines as Multimodal Storytelling

Chris Landry has said “Zines take the profit and fame motive out of artistic expression and focus on communication, expression and community for their own sake. Zines are the one truly democratic art form. Zine writers are the most important writers in the world” (n.d). Taking Landry to heart, in the fall of 2024, the authors, Anna Rue and Marcus Cederström, collaborated to assign research- and fieldwork-based zines as a final course project to students in an advanced folklore course (Local Culture and Identity in the Upper Midwest) and an introductory course (Cultures of Sustainability: Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe), which was designed specifically for what UW–Madison calls FIGs (First-Year Interest Groups). FIGs have up to 20 first-year students who take a seminar-based class along with two additional and related lecture courses. In this case, the FIG included Introduction to Environmental Studies and Introduction to Folklore.

We turned to zines to create a sense of community and challenged our students to think and communicate creatively through the creation of their own version of folk culture. As Alison Piepmeier writes, “In a world where more and more of us spend all day at our computers, zines reconnect us to our bodies and to other human beings” (2008, 214). We found zines to be an excellent form of multimodal storytelling for our students that challenged them to use their hands along with their minds. In creating a zine, students made connections between the physical and the abstract, communicating cultural and traditional knowledge in the form of a specific folk art—the zine.

We scaffolded the work beginning almost immediately in our 14-week semester and made sure that the assignment aligned with learning outcomes for the class. In Marcus’ class, for example, the assignment was mapped to two (out of five) specific learning objectives/outcomes:

- Analyze the causes of and proposed solutions for the sustainability challenges of culture with regard to social, economic, and/or environmental issues in Central, East, and North (CEN) European contexts.

- Present your understanding of sustainability to a variety of audiences, including scholars and the general public.

For most of the students, making zines was new. Only a couple had made a zine before, and only a handful even knew what they were. So, the third week of class was dedicated completely to learning about zines. Students in the sustainability course first met with Todd Michaelson-Ambelang, a librarian at UW–Madison. Upon arrival in UW–Madison Library’s Special Collections, he directed students to a wide array of zines and related publications, including underground newspapers, cartoneras, and other forms of book art. Students in the Local Culture course visited the librarian Megan Adams in the Information School Library, home of the Library Workers Zine Collection. Visiting these collections in person gave students a hands-on opportunity to learn about the form, see examples, and understand that these radical forms of literature were being collected, recognized, and preserved at the University.

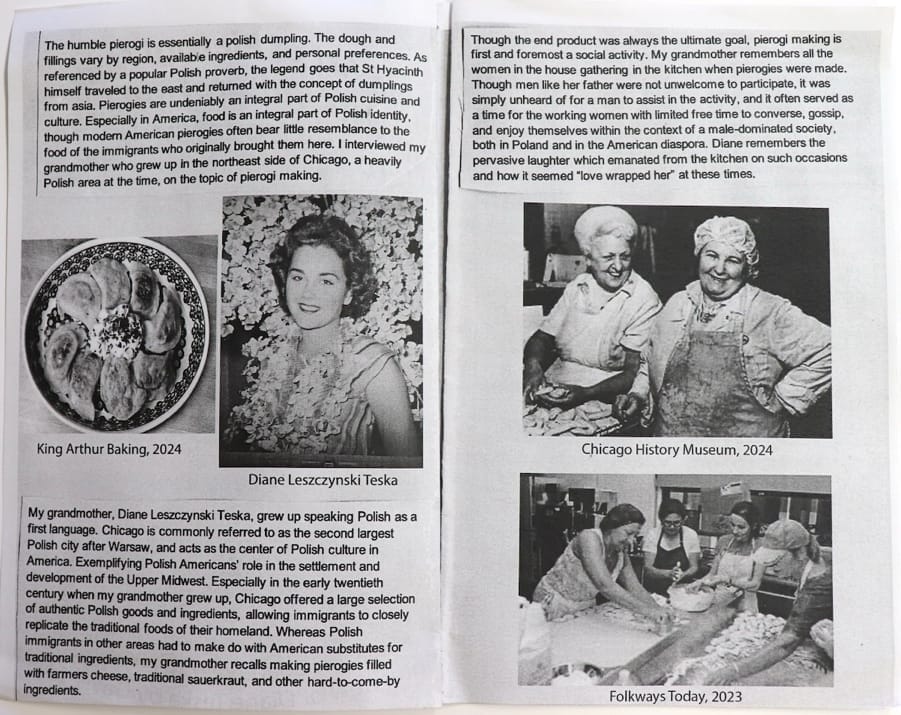

- Pages of a zine made by undergraduate student Davis Yewell. Davis’s zine was based on an ethnographic interview he conducted with his grandmother about the pierogi-making traditions in their Polish American family.

One student drew extensively from this visit, writing at the end of the semester, “The inspiration for my zine arose from many environmental justice newspapers, especially the Earth First! newspaper. These had an understandable argumentative tone, which called people to action by recommendations and examples of stories. I was also really drawn to their style of collage, adding text, pictures, and drawings into the pages of their newspaper.”

Of course, not every library has a zine collection, although more libraries are carrying zines in their collections. However, there are many online collections, digital libraries, local infoshops, bookstores, and independent artists selling or distributing their zines for free. Good resources include the Barnard College Zine Library, the Library of Congress, and the Denver Zine Library. While we are lucky to have such wonderful collections right on campus, zines, because of their do-it-yourself nature and their focus on accessibility, can readily be acquired throughout the country. In the past year, we’ve picked up zines at book swaps, conferences, farmers’ markets, bookstores, and a variety of community events.

Following our visit to the library, we invited to the class Camy Matthay, a zine maker and, as we introduced her, “a bona fide iconoclast, social justice activist, and at this point, only a part-time lumberjack.” Matthay is co-founder of the volunteer-run nonprofit Wisconsin Books to Prisoners, which sends free books to incarcerated individuals throughout the state, and she was also involved in starting Madison’s Print & Resist Zinefest in 2004. In preparation for Matthay’s visit, students read one of her zines to further familiarize themselves with the format. Matthay’s Intro to Zines: a brief history and how to make them is a short, easily accessible, and incredibly rich introduction to zines and zine culture, with great advice on how to create a zine (2019).

In class, Matthay discussed the history of zines and zine culture, as well as the role of place in zine making—from the importance of surreptitiously copying zines in your office, to a hyper-focus on local places for inspiration, to finding places to distribute the zines. This discussion made clear to the students that zines should be considered a form of folk art that was grounded in tradition, but also constantly changing. She also brought scores of zines from her collection for students to look through, including titles like “Yum Yum” about food and agribusiness; “Cellphones Suck” about the effects of cellphones on miners and the environment in the Republic of Congo; “Community Bike Car Design” about bicycle ambulances in Namibia; and “Disorientation Manual,” which Matthay noted had been “produced annually for UW students for at least a decade by a collective of local anarchists,” although that collective is now defunct (personal communication 2024).

Matthay, along with Anna and Marcus, planned ample time for discussion. Doing so gave students an opportunity to engage directly with zines by touching and reading them, which allowed them to see the wide range of styles and take inspiration for their own projects. In addition, students experienced zines as important, recognized by professionals and activists like Matthay, and even noteworthy enough to be archived in state institutions like libraries at UW–Madison.

Over the course of the next ten weeks both students and instructors—as we committed to creating a zine alongside our students—began work on our zines. Students were tasked with choosing their own topic and how their zine would look. In Marcus’s class, the zine was based on the intersections of culture and environment and was required to be handmade (no digital software allowed), eight pages, and a combination of text and images. In Anna’s class, the zine project was based on an ethnographic interview each student conducted about a cultural group or practice in the Upper Midwest. Students focused on describing a cultural activity practiced by their interviewee and presenting it to a general audience. While Anna’s class zines had to be printed out and assembled by hand, digital tools were permitted in their creation, although most students incorporated handmade elements. Students in both classes turned in a hard copy to their instructor and made copies for their classmates. We made it clear that we would not be grading their artistic abilities and instead focused on their ability to communicate their research and fieldwork efficiently and effectively in the zine.

In addition, students submitted a written statement that described their vision and inspiration and discussed how both were represented in their final zine. Anna’s students were asked to reflect on their intentions, inspiration, and choices around representation. In Marcus’ class, students had previously written a research report on a sustainability topic of their choosing. Their zines explicitly did not include additional research. Instead, the zine-making assignment was meant to challenge students to present their research in new, creative, and accessible ways to a different audience.

In this case, that audience included their peers. Regarding the zine and their goals for publishing it, one student wrote, “My frame of sustainability was widened to include culture and community systems. Before I hadn’t seen the importance in a widened frame but now I can understand how they are all connected. This is my hope and goal for my readers.” Over the course of the class, this student considered the intersections of culture and community with sustainability—a key learning objective for the course. Importantly, they also used their zine to make clear these connections, demonstrating what they had learned and sharing that knowledge with others. In Anna’s class, one student’s project on the card game sheepshead was created with two functions in mind, writing, “Creating a zine about sheepshead allowed me to share the game…in a way that I couldn’t have by just explaining it to them. The zine offers a physical explanation of the rules through text and images while also getting a glimpse into the life and story of someone who lives it. A zine about sheepshead would be great for anyone interested [in] learning about Wisconsin culture and identity.” Here we see a student thinking critically about the benefits of a multimodal form of storytelling, incorporating their fieldwork into the how-to of the game made for a richer and more engaging final product. And, of course, the student created a form of folk art that also preserves community traditions and amplifies the voices of those who participate in those traditions.

Other students who focused their zines on ethnographic interviews conducted with friends or family members considered their zines to be important documents to share within their personal networks. Those projects included interviews with a grandmother about family pierogi-making traditions, a muskie-fishing father, and a waterskiing brother. In these cases, the fieldwork conducted created documentation of these regional cultural practices as well as unique family folklore productions. Upon completion of her zine one student wrote, “I was extremely excited to share insider knowledge on a unique sport I have a deep respect and admiration for. I feel I proficiently conveyed the specialness of this art and its importance to the Upper Midwest. I commemorated my family by telling our story, while providing detailed insight to the complexities of water/show skiing. I am tremendously proud of my finished product, the story I told, and my real-life field work as a folklorist!” Just as with the sheepshead zine, the water/show skiing zine reflected and lifted up a local tradition with a goal of telling a unique story and contextualizing it in the rich culture of the region.

In addition to the hands-on work that went into making a zine, we wanted to make clear the communal aspects of zine making. So we hosted a zine social. We invited Matthay back to campus and brought our two classes together. We had snacks, drinks, and enough zines for everyone to trade with others. Some students were frantically folding their zines as our social began, and at first the students stayed with their own classmates. As the hour went on, however, more people began wandering around, trading zines, and chatting with others. As a result, our students experienced firsthand that zines “focus on communication, expression, and community” (Landry). In discussing with each other, including their own classmates as well as students they hadn’t met but who were doing similar things, they realized that they were now part of a community—larger than just one assignment, or one class. Matthay’s presence helped reinforce that community extended even beyond one course: They were in community with zine makers, they were a community of zine makers. The focus during the event wasn’t the grade per se, but the celebratory realization of being in community.

Zine made by Vivian Silva in 2024 for GNS 210. Vivian used found materials like cardboard, excess yarn from an in-class weaving project, and magazines to complement her own art work in her zine.

Student Zines

Matthay confided in Marcus that she was a little skeptical when she heard our plan but was blown away by the results. So were we. Zines have been one of our most successful final projects. Making them easily mapped to course objectives, and scaffolding the project over the course of the semester meant we could incorporate the project into readings and class discussions throughout the semester. As Jeanne Scheper writes, zines are an “intriguingly reinvigorated pedagogical tool with potential applications in many learning contexts, from community-based activism to the university classroom” (2023, 21). We agree and have found that zines are easily transferable to a variety of classrooms because of the multimodality inherent to their creation and their analog form. In fact, as we have seen in our classrooms, zines allow for a wide variety of skill building. Students conduct scholarly research with primary and secondary sources and ethnographic documentation. They are asked to read closely, think critically, and write analytically, all while synthesizing their work into just a few short pages of a zine. In this assignment, critical thinking and creativity are crucially integrated. In the sustainability course, for example, several students, writing about waste management systems, used recycled paper, recycled cardboard, and other found and repurposed materials to create their zines, making explicit connections between the assignment, the materials, and the course topics. In the regional folklore course one student expressed the success he had with creative, critical thinking about his family’s foodways traditions. “I wanted to use a firsthand account of the practice combined with scholarly research to exhibit its importance to the culture and identity of the Upper Midwest. I was also inspired to make my zine at least partially by hand, aligning the text and images using paper and glue.…I learned both about the cultural significance from scholarly sources and anecdotes and history about my own family. I’m excited to share copies with family and friends, and especially my grandmother. These intentions and inspirations are represented by multiple creative choices I made.”

The openness of the project allowed students to flex their creative muscles and think very deliberately about how to connect with a real-life audience of their peers who would receive a copy of their work. One student wrote, “Since being at college, I haven’t had a lot of time to sit and just draw for hours, so this project really brought back that creativity that I have been craving.” This student, having not read Kuhn, makes clear the assumption that college is not a place for creativity, not a place for hands-on learning. Assignments like zine making push back against that assumption and allow students to use more of themselves in the learning process.

Students walked out of class with zines in their hands and a much better understanding of how to synthesize and present complicated research. For some students, who are less comfortable expressing themselves in writing, this project struck a good balance. One wrote, “Creating a zine was a project that allowed for a lot of creativity that I have never been able to express through just writing.” Another student reflected, “I really enjoyed the interview assignment and it allowed me to learn more about my family and bring the lessons from class to my real life and share with others. Additionally, the final zine project was a super cool assignment and gave me a keepsake that I am proud to have created.” Zines as a form of multimodal storytelling made for a more accessible final project. Plus, students now have a new level of expertise in their very niche field.

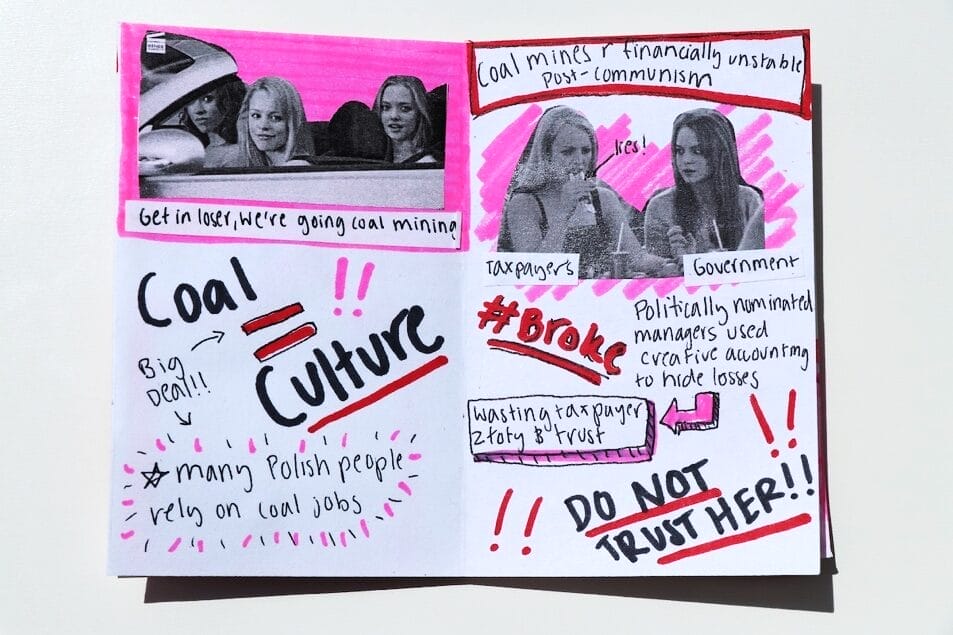

- Front and selected inside pages of zine made by Alexandra Holubowicz in 2024 for GNS 210. Inspired by Mean Girls, Alexandra’s zine incorporated pop culture references throughout. Alexandra connected climate change, culture, and labor in her zine on coal mining in Poland.

Lessons for Next Time

Zines in the folklore classroom proved to be an incredibly effective way to engage students with ethnographic skills, writing skills, and critical-thinking skills and students’ feedback and assessment suggest it was very successful. For future iterations, we have identified further ways to adjust the assignment in the hope that students will be able to learn even more from the project.

First, in preparatory discussions for her visit to class, Matthay suggested an in-class collaborative zine-making exercise based on a prompt we would give the students. Students would be given a pen and a half-sheet of paper and asked to reflect on the prompt for five to ten minutes before turning their ideas in to the instructor to compile, photocopy, and distribute to the class. Matthay has used this activity successfully with elementary school classes and the college classroom seemed a good next step. However, our students spent so much time discussing the zines that there was no time for making a zine. This was a mistake on our part. Creating a collaborative zine, as Matthay suggested, would give students an opportunity to learn and make and do together. Relatedly, incorporating more zines into the curriculum, making more space for students to read and touch zines, and encouraging using zines as sources for their own zines would allow for a better understanding of the format before students make their own.

While we made clear that we would not be grading students on their artistic abilities, many students expressed anxiety about their drawing skills and their creativity in general. Incorporating a wider range of zines throughout the class, allowing them time and space to make together, and showing our own zine-making attempts in class would, we believe, mitigate that anxiety. Additionally, the graphic journalist, cartoonist, and educator Lynda Barry of UW–Madison has long worked to combat the common belief some people have that they can’t draw by publishing excellent guides for lowering barriers to creative expression. Introducing exercises inspired by Barry’s work (Making Comics (2019) and Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (2014), in particular), would support students by providing tools and skills for drawing, creating low-risk opportunities to practice in class, and helping them understand the true intent of the zine assignment.

- Inside and back pages of zine made by Bella Wittwer in 2024 for GNS 210. Bella made explicit connections between climate change and culture in their zine. Students were encouraged to think creatively about the use of citations in zine culture, but had already turned in a list of citations to the instructor earlier in the semester.

We gave our students a lot of freedom to create and were proud of their productions. At the same time, depending on the level and the course content, additional scaffolding may be useful. Reserving class time for students to share ideas, early drafts, and discuss their research could jumpstart the reflection process. We hosted our zine social on the last day of class, so there was no time to discuss our experiences in person. Written reflections were excellent, but ensuring more space for discussion also centers the communal aspect of the project and zine culture.

Finally, ensuring that we have a better collection of print materials for students to cut and paste from would be incredibly beneficial. Most students do not subscribe to physical print publications, so sourcing the materials themselves for all the students who wanted them became a challenge.

While there is always room for improvement, overall, this is an easily replicable and adaptable hands-on assignment that encourages students to think critically about the course content and how to creatively represent it using physical materials.

The back page of a zine made by undergraduate student Davis Yewell featuring his grandmother’s pierogi recipe. Reflecting on his intentions for creating this zine Yewell wrote, “I included some specific family recipes on the back to both provide a starting point for those wishing to make their own, and to reiterate the hereditary and familial aspects of the pierogi making tradition.”

The Most Important Writers in the World

As Landry says, in this exercise our students became the most important writers in the world. And they seemed to connect deeply with that idea. Several students commented on the accessibility of zines and made explicit their understanding of zines as a form of grassroots folk art. One student wrote, “I would like to do more zines in the future. I think they are a really good way to get information out to people in a cheap and accessible way. I really enjoy the way it turned out and enjoyed having a creative project to work on amongst all the papers and tests I had to do.” A second commented, “I found the overall process to be fun and inspiring, and appreciate that, with a vision or inspiration for communicating a topic, it is relatively simple to get information out there that catches people’s attention.”

And sure enough, they did. Nearly every semester, folklore courses across campus at UW–Madison begin with various “find the folklore” assignments. Often, these include photographing an example of campus folklore. At UW–Madison, that commonly means a photograph of the foot of the Abraham Lincoln statue that sits atop Bascom Hill. Students have for years rubbed the foot for good luck. The spring 2025 semester, however, saw one student submit a photograph of a zine featuring a cut-and-pasted image of Josef Stalin, drawings of pigs, and a description of a Soviet scheme to feed food scraps to pigs to increase pork production for the USSR. That zine, written, drawn, and designed by a student in a fall 2024 folklore course, had been left around campus, only to be found by a future folklore student.

There is a burgeoning body of research making clear the connections between craft and improved social, emotional, mental, and even physical well-being. Through assignments like zine making in the folklore classroom, we are trying to make clear the connection between our physical being and our mental learning, to remind students that it’s not just our brains that help us learn, but our arms and legs and hands and feet, our peers, our instructors, our environment. Embodied learning can make abstract learning easier and more accessible. There are valuable lessons to be learned and retained for all of us from every class we take, even for those who never take another folklore class. We are, as Sarah Kuhn writes, trying to make clear that “All learning is experiential. In understanding that, it is critical that our assignments, our syllabi, and our classrooms ensure students learn to act and learn to learn” (2021, 183).

Marcus Cederström is a public folklorist working in the Department of German, Nordic, and Slavic at UW–Madison as the community curator of Nordic American folklore for the “Sustaining Scandinavian Folk Arts in the Upper Midwest” project. His research interests include immigration to the United States, Nordic and Nordic American folklife, Indigenous studies, and sustainability. Cederström teaches folklore courses, conducts fieldwork with Nordic American and Indigenous communities throughout the Upper Midwest, and works with a wonderful team to create public programming and productions supporting Nordic, Nordic American, and Indigenous folk arts.

Anna Rue serves as Director of the Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures at UW–Madison and teaches folklore courses on regional and Nordic American folklore in the Folklore Program at the Department of German, Nordic, and Slavic+. Rue also works on the “Sustaining Scandinavian Folk Arts in the Upper Midwest” project and her research interests include folk art and music, and Nordic American and regional identities and communities.

Works Cited

Barry, Lynda. 2019. Making Comics. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

—. 2019. Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor, Spring Semester. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly.

Ben-Amos, Dan. 1971. Toward a Definition of Folklore in Context. Journal of American Folklore. 84.331:3-15.

Bobrow, Evan. 2025. The Role of Academic Libraries in the Shifting Landscape of Zines. College & Research Libraries. 86.2, https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/26688/34587.

Creasap, Kimberly. 2014. Zine-Making as Feminist Pedagogy. Feminist Teacher. 24.3:155-68.

Kempson, Michelle. 2015.’My Version of Feminism’: Subjectivity, DIY and the Feminist Zine. Social Movement Studies. 14.4:459-72.

Kuhn, Sarah. 2021. Transforming Learning Through Tangible Instruction: The Case for Thinking With Things. New York: Routledge.

Landry, Chris. n.d. FAQ + Contact. Microcosm Publishing, https://microcosmpublishing.com/faq#why-focus-zines.

Matthay, Camy. 2019. Intro to Zines: a brief history and how to make them. Madison, WI.

—. Email message to authors, August 25, 2024.

Piepmeier, Alison. 2008. Why Zines Matter: Materiality and the Creation of Embodied Community. American Periodicals. 18.2:213-38.

Scheper, Jeanne. 2023. Zine Pedagogies. The Radical Teacher. 125:20-32.

Toelken, Barre.1996. The Dynamics of Folklore. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Wan, Amy J. 1999. Not Just for Kids Anymore: Using Zines in the Classroom. The Radical Teacher. 55:15-19.