Un choque.

Choque pi ta pom ta ria.

Choque pom.

Pi ta. Pi pi pi ta. Ta ria.

Choque pom.

Ta ria ria pi ta ria ria pi ta ria ria pi ta

choque pom.

Pom pom.

The onomatopoeia of the castañuelas speaks out. They are the disruptive force in the colonially induced quiet of the ivory tower.

This ivory tower contains dance studios with floor-to-ceiling mirrors and ballet barres framing the perimeter.

These studios hold our dancing bodies.

We sense a tension between the familiar and the foreign. These spaces call to our Western concert dance training. Yet as many post-secondary dance programs eagerly seek more “diverse” offerings today, we are now invited to bring our communal dances as well.1 For us, this has meant embracing the dances and rhythms of our youth, such as the castanets, cante, and palmas that enrich the Sevillanas tradition, a partner folk dance from southern Spain.

We hold space with our rhythms echoing off the mirrors. The sound bounces back, and we insist on being heard. The clashing, the choque, questions what these dance spaces are made for. The university’s architectural colonial imposition on the Indigenous lands (now known as the United States) holds memory. It holds many dancing stories, migration stories, and stories of diasporas dancing back to their homeland. This is our dancing story.

Un Choque

The choque is where the heart and the flesh of our story lives. We look to the choque, the literal crashing of the castanets together, as a metaphor for the collision of cultures, histories, practices, and values when concert dance and folk dance traditions coexist within the changing contours of an academic studio.2 We embrace this choque in our current faculty assignment, teaching Spanish Dance through the Special Topics course series within a predominantly ballet and modern dance university program. This leads us to ask—how do we ethically, respectfully, and responsibly teach communal folk dances in post-secondary dance spaces, often saturated with inherited Euro-American values of concert dance? To consider the complexities of such negotiations, teaching between the familiar and the foreign, we begin by tracing the lineage of our Sevillanas experiences through an autoethnographic reflection of our own dancing migrations.

Our Sevillanas Stories

Roxanne’s Sevillanas Story

My Sevillanas tradition is rooted in my childhood in San Antonio, Texas. I learned the Spanish folk dance through my Flamenco and Folklórico dance classes at the San Antonio Parks and Recreation Department. This city program provided accessible and affordable learning and performance opportunities for youth. Many of my childhood weekends were spent performing at fiestas, quinceañeras, parades, and city functions at El Mercado or The Riverwalk. I have happy memories of sweating in the Texas heat with lipstick-stained stage smiles and brightly colored raspa rewards at the end of every performance. My instructor, Marisol Flores Millican, eventually started her own performing group outside the Parks and Rec program, where I continued studying dance. The learning of these various Spanish and Mexican dance traditions was inextricably entwined in San Antonio, a way for diasporic Tejanx subjects to reconnect with their multiple cultural roots through migratory dances. At performances, I would seamlessly change costumes in a “backstage” vinyl tent—removing a colorful Jalisco dress and slipping into a polka-dot, ruffled skirt to dance the Sevillanas. These dance forms were the foundation of my borderland identity and provided me with a direct connection to my ancestors through embodied communion.

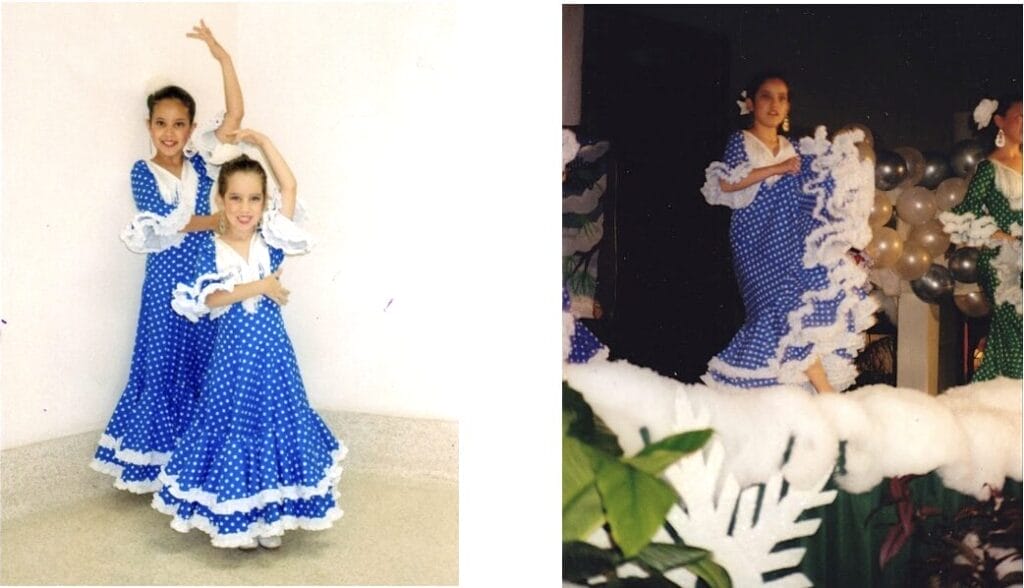

Left: Roxanne and her younger sister, Danielle, posing in Sevillanas costume.

Right: Roxanne performing Sevillanas with the San Antonio Parks and Recreation Department. Photos courtesy of the authors.

My Flamenco and Folklórico classes included a variety of regional dances from Spain and Mexico. We always had a Sevillanas folk dance in our performance lineup. While our classes were divided into age groups and technique levels, every class learned the Sevillanas and often performed them together. This dance was the common connection between the classes, from age four to adult. It provided a bridge between generations that dissolved hierarchies of age and technique. No matter which class you were in, you had a polka-dot dress.

While I spent my weekends performing on the West side of San Antonio, my family lived in the predominantly white suburbs of North San Antonio. When I reached middle school, I opted for a change, studying ballet and jazz at the San Antonio School for the Performing Arts. It wasn’t until later in life that I recognized this decision’s assimilative impact on my dance journey. While attending graduate school in Salt Lake City, I reencountered the Sevillanas in a local class taught by Solange Gomes. Although my days were filled with taking and teaching modern dance classes on campus, I yearned for an outside community outlet. I found that the zapateado and rhythms came naturally to me in these classes, recalled from my youth. As we danced the Sevillanas, I recognized the patterning immediately. But when we were asked to turn toward a partner and initiate that flow of pasadas around each other, I was thrown. I realized it had been a while since I was asked to connect with another body in such a way, having worked in proscenium performance for so many years. The social aspect of dance was a distant enough memory in my embodied practice that it took effort to recall the approach. Adding castanets tipped me over the edge, asking me to engage in a polyrhythmic, polycentric technique that had apparently gone latent in my body. Dancing the Sevillanas was comforting and frustrating—a familiar muscle memory I couldn’t execute because those muscles had atrophied.

A work-in-progress performance of Roxanne’s thesis choreography, “Faldeo.” Photos courtesy of the authors.

I am currently completing my thesis research for graduate school and teaching in the university program. My creative practice explores borderland identities through modern and Folklórico dance, and I employ Chicana feminist methodologies in my teaching practice. I have noticed similarities between teaching Spanish Dance in our Special Topics course and teaching Folklórico faldeo and zapateado techniques in my rehearsals. The students in my cast are approaching this new technique from various dance backgrounds and experiences. Adding the unfamiliar skirt, rhythms, and cultural context allows everyone to arrive at our creative process at the same level, and we have built a community of learning in the space.

Recently, I went home to San Antonio to visit my family and take a class with my mother, who is still dancing in her 60s. Her class is taught by my childhood maestra, Marisol Flores Millican, who drills the zapateado with a sharp eye and a booming laugh. I was pleased to discover that the group was also working on the Sevillanas. After reconnecting with the dance during my classes in Salt Lake City, I could easily jump in and partner with my mother. With every turn, I could feel the intergenerational pull of the coplas drawing me into the dance like an invitation. It was an invitation to remember—a cultural memory embodied by both my youth and my ancestors.

Kiri’s Sevillanas Story

I carry the Sevillanas tradition from the Boston Ballet School, Southern and Northern New Mexico teachers and their dance groups, the local dance studios and community college in the U.S./Mexico border town of El Paso, and the American Bolero Dance Company and Ballet Hispánico School of Dance in New York City. In both the Southwestern and the Northeastern U.S., the Sevillanas were an integral tradition—building community, connecting to heritage, and blossoming intergenerational and cross-cultural understandings. As I studied, performed, and taught the Sevillanas over the past three decades, I developed an appreciation for the malleability of the dance as a catalyst for personal expression, exploration of self and others, individual and collective identity-making, and a way of knowing and asserting through the body. I continue to learn new lessons as I dance, sing, play the castanets, and pass on the tradition of Sevillanas today in Salt Lake City.

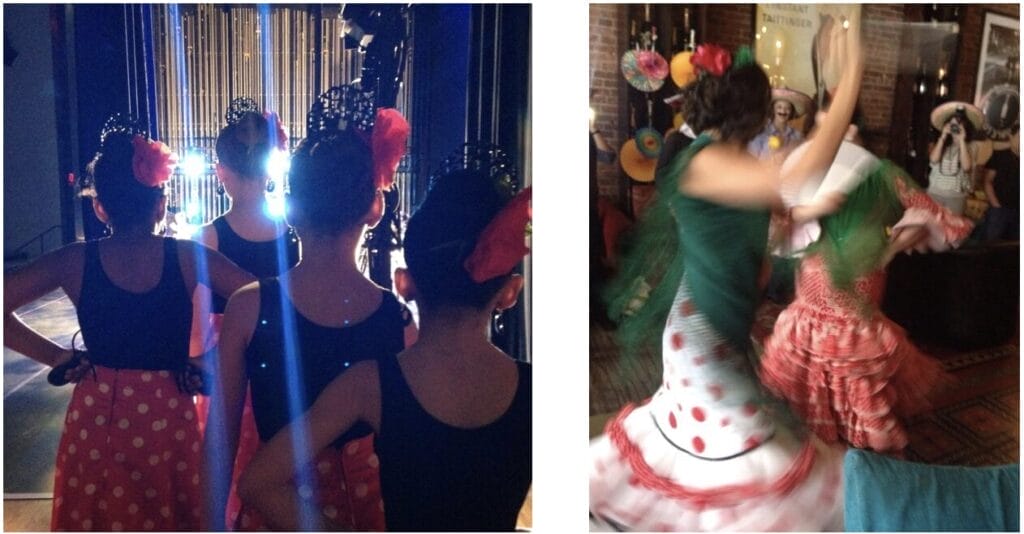

Left: Ballet Hispánico students waiting backstage to perform their Sevillanas for the end-of-year dance recital. Right: Kiri performing Sevillanas with her colega Franchesca Marisol Cabrera at a restaurant in Lower Manhattan, NYC. Photos courtesy of the authors.

My first encounter with this Spanish folk dance was at the Boston Ballet School in Massachusetts one hot summer in 1996 as a young teen under the instruction of Ramón de los Reyes. I remember needing to be fully engaged with the class (I was not) and feeling overwhelmed by the rhythmic phrasing and the necessary partner work. In reflection, growing up as a “bunhead” with a tunnel vision for ballet, my training did not instill values of appreciating anything other than ballet. Being forced to learn the Sevillanas in his Danza Española class didn’t feel good. I wasn’t invested. Nonetheless, I participated, as it meant I could progress in the program and move on with my professional trajectory in dance, one I thought would continue with a focus on ballet.

As a young adult, following my early career as a professional ballet dancer, I made a sharp shift in direction. I returned home to El Paso, Texas/Cd. Juárez, Chihuahua, left ballet, and wondered where dance would take me next and if it would be with me at all. Once home, I was most welcomed in the El Paso Community College dance classes at the Valle Verde campus in the Lower Valley by Rita Vega de Triana, the wife of late Flamenco artist Antonio Triana. They relocated to the border town, and following his death she continued his legacy, teaching Clásico Español, castanets, zarzuelas, and the Sevillanas to the young college students. Her immaculate castanets would purr through the studios every Saturday morning. Her introduction of the Sevillanas brought me back to my closed-minded, silo-visioned teenage self. However, with more maturity, I was more appreciative of the Sevillanas. It felt good in my body, it felt fun, and it gave me a relationship with my classmates with whom I would have otherwise had no interaction. The Sevillanas brought common ground to our diverse group of students with varying degrees of dance experience and levels of coordination and rhythm. The communal aspect of dancing the Sevillanas brought joy back to my dancing, something I had lost along the way as I pursued the highly competitive and personally demanding world of professional ballet.

I noticed the contours of home had changed as I returned from the East Coast. Home felt different now, reshaped through the diasporic dances I began to study in new and meaningful ways. Being back in my homeland, reconnecting to the communal spirit of dance through the Sevillanas would ultimately facilitate a return and the remembrance of my cultural roots as an artist in diaspora, something that ballet had negated in my formative years of training.

Kiri performing the Sevillanas with her American Bolero Dance Company colegas at their Friday night tablaos in Queens, NYC. Photo courtesy of the authors.

I would continue my studies of the Sevillanas at a local dance studio on the West side of El Paso that taught Ballet Folklórico and Flamenco. I also learned the castanets, studying at New Mexico State University, the National Institute of Flamenco’s Flamenco Festival Alburquerque every summer, and the University of New Mexico. My intensified training in Flamenco, Spanish folk dance, and Clásico Español throughout the borderlands region would become my second career, performing with regional dance companies and artists. The Sevillanas would remain a staple in our repertory—at theaters, local venues, small restaurants, city plazas, and fiestas. This path would continue leading me to new spaces, and I eventually moved back to the Northeast to dance with the American Bolero Dance Company (ABDC) and Ballet Hispánico (BH) in New York City. Moving back and forth between the East Coast and the Southwest, the immersion in folk dance facilitated my understanding and appreciation of my rich cultural heritage as a diasporic participant. My dancing migrations helped me “find” my culture in new ways by connecting me to new dancing communities in diaspora.

My 11-year tenure in New York City performing and teaching with these companies would build on my foundational experiences in Boston, New Mexico, and El Paso. My maturation as a Spanish dance performer in the tablaos and my pedagogical curiosities for this dance form would be nurtured by working with and learning from many colegas in the city. I began to work intentionally with other teachers to center the Sevillanas in our dance curriculum at BH. This move would build a sense of convivencia as teachers and músicos, within and across our classes, amongst the student body, and with the families and school administration.3

As a new ABDC company member, dancing the Sevillanas with my colegas at the Friday night tablaos forced intimacy. It gave us an equal footing as performers, regardless of our ranking or seniority in the company.

Ballet Hispánico students performing the Sevillanas at the West Side Community Garden in Manhattan, NYC. Photo courtesy of the authors.

At BH, the Sevillanas was an invitation for our classes across age groups and divisional programs (pre-professional and “open” classes) to collaborate, admire, encourage, and be together, celebrating across differences. It became a rite of passage for the students and something unique they would bring to citywide dance festivals with The Ailey School, Dance Theatre of Harlem School, Limón Professional Studies Program, Martha Graham School, and Peridance Center. These cross-city collaborative encounters through shared performances brought a sense of orgullo to the students of BH. By performing the Sevillanas, which stemmed from their BH dance lineage, and for some students, also connected to cultural heritage, they realized they had something special to share with their peers.

Our Stories Today

In reflecting upon our shared Sevillanas stories, we have found overlaps in our learning, performing, teaching, and revisiting of this Spanish folk dance—for example, the impact of working intergenerationally, easing hierarchical norms, and emphasizing socialization, something that Western concert dance spaces often negate. At separate times in our lives, we revisited this dance and discovered the joy and communal feel we thirsted for in academic dance spaces. At the same time, our experiences were rooted in different geographic regions and migrations, types of dance environments, and instructional approaches.

As we continue building a diasporic Spanish folk dance lineage in our classroom today, our embodied teaching genealogies encourage a pedagogy that ethically, respectfully, and responsibly teaches communal folk dances in post-secondary dance spaces.4 As dance forms migrate to new spaces, communities, and bodies, we acknowledge the process of pedagogic acculturation (Medina and Mabingo 2022). To illustrate such pedagogical negotiations, we offer insight from our class.

Folk Dance Considerations: Plática, Emergent Strategy, and Care Through Chicana/Latina Feminist Pedagogies as Culturally Relevant and Responsive Strategies

Although our Spanish Dance course was offered to the entire dance program, the students enrolled were from the undergraduate modern dance major and minor. This small and diverse group included female-identifying students and one genderqueer student. The students identified as Mexican American, African American, Asian American, Irish American, and Euro American, hailing from Illinois, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. At the university, these students train in modern dance and hold prior experience with high school dance, drill, and cheer teams; competition dance studios focusing on lyrical, jazz, tap, and ballet; and Latin and European social dance through ballroom dance competitions. In addition, a few have vocal training and have studied Spanish as a second or third language.

We started with castanet training on day one to allow students an entire 16-week semester with the musical instruments.5 Introducing castanets through Danza Estilizada—a stylized Spanish dance that draws on elements of folk, Flamenco, and Escuela Bolera—allowed students to simultaneously use their concert dance technique and familiar movement vocabularies such as abrir y cerrar (tendus), paso de vascos (waltzes), and vueltas (turns).6 Following this first unit on Danza Estilizada, we introduced students to Spanish/Andalusian folk dance through the Sevillanas. This is where our Sevillanas stories were enacted, and we began to draw upon the intersection of our migratory dance lineages.

Going into the course, we knew that we would need to till the ground in culturally relevant and responsive ways to honor the historical context and migrations of these dance forms and the specific demographic of students who made up the class.7 We centered critical conversations, introducing the practice of plática as a Chicana/Latina feminist pedagogy in every class.8 Through these intentional class pláticas, we first asked, “What do you think Spanish dance is?” This initial plática helped everyone assess their understanding of the art form. It disrupted any assumed definitions of the tradition, ensuring that diasporic experiences and contributions to the form were recognized and an acknowledgment of its evolution through ongoing migration was underscored. As this was a new form for everyone in the room, we wanted to provide different avenues of learning to support the embodied practice and class pláticas, using PowerPoints, videos, articles, and resource books that further contextualized and underscored the complexity of the art form.9

Prioritizing Chicana/Latina feminist pedagogies as culturally relevant and responsive strategies honors the cultural and historical context of the dance, respects the students’ backgrounds and experiences, and centers an ethic of care in our teaching.10 One example of this work was co-creating community class agreements so that everyone had a say in how our class would flow and how we would work together. We noticed that students were most concerned with respect for the art form as well as respect for each other in a new learning process:

COMMUNITY CLASS AGREEMENTS

- Taking the time you need, asking for help when needed

- Supporting each other in a vulnerable environment

- Valuing cultural context

- Acknowledging and respecting our differences

- Be curious and inquisitive

The second example was asking students to fill out an index card with information about themselves. Our hope with this exercise was to gain insight into students’ interests and career trajectories so that we could bridge their prior experiences to the current class material and support what they wanted to do with it. This acknowledgment of students’ prior knowledge honored them as co-constructors of learning in the class and resisted the banking model of education (Freire 1970).

PERSONALIZED INDEX CARDS

- Preferred Name and Personal Pronouns

- Year in School and Major/Minor of Study

- Previous Dance Experience

- What Do You Hope to Get Out of the Class?

As the class progressed over the weeks, our pláticas continued, and the class gave itself permission to stop when questions or concerns arose. For example, when we introduced the social-participatory layers of Sevillanas, such as jaleos (shouts of encouragement), one student was concerned that using vocalization in a language she didn’t know would be considered appropriation. We followed her lead, paused the class, and engaged in plática to think through previous experiences in other classes. The students discovered similarities between dances they have studied, such as the call and response used in some West African dances or the communal freestyle nature of Hip-Hop cyphers. From our pláticas on these communal dance practices, we acknowledged that to participate responsibly and respectfully in our study of the Sevillanas, engaging in these layers, such as the jaleos, palmas, and, at times, singing, is essential. Some students felt more like “outsiders” because they did not know the Spanish language primarily used in jaleos, while some knew the language, yet it wasn’t part of their cultural heritage. In addition, because of their concert dance training, they generally did not have the experience of vocalizing and dancing. This student-initiated plática on appropriation and unfamiliar experiences stemmed from the realities of migratory dances embodied in Western concert dance spaces.11

Embracing the Choque: A Need for Disruption

The migrations of folk dances into Western academic spaces disrupt concert dance expectations and invite new pedagogical negotiations. As illustrated, we used class community agreements, personalized index cards, and class pláticas to anticipate the choque. While teaching Sevillanas, we discovered that the choque, the collision of cultures, histories, practices, and values (Anzaldúa 1987), was not something to be resolved but embraced. By working to respond to the emerging needs of our class and trusting our embodied teaching genealogies, our classroom became a fertile ground for strategies to emerge.12 We would like to name these strategies as disruptors—pedagogical tools to navigate the choque.

For example, the early introduction of castanets was a newfound challenge to dancers at an advanced level in other genres (e.g., ballet and modern) yet new to folk dance. This brought everyone to the same level of new learning through the “universal unfamiliar”13 (castanets), negotiating between the familiar and the foreign. As Boricua Spanish dance artist, educator, choreographer, and writer Sandra Rivera details in her essay, “Spanish Dance in New York City’s Puerto Rican Community” (2021), the implementation of castanets as a layer in Spanish dance studies provides a challenging complexity that keeps students engaged, demands heightened attention to the rhythm and instrumentation of the song, and requires a nuanced interpretation of the music in playing alongside the musical score. We embraced the choque of students’ various techniques, experiences, and interests and realized the castanets became a pedagogical disruptor.

In conclusion, we offer seven potential interdependent disruptors for folk dance practitioners to consider when teaching concert-trained dancers in Western academic spaces.

DISRUPTOR APPLICATION A “Universal Unfamiliar” ❖ Introduce something unfamiliar early in the semester (e.g., a way of moving or a material element such as castanets, the falda, an abanico, etc.) to bring everyone to the same level of new learning through the “universal unfamiliar.” ❖ Acknowledge this newfound challenge and encourage an attitude of discovery, an environment of support and respect for the technique and/or material element.

___________________________________________________________

Address Hierarchies

❖ Be deliberate in naming and addressing the hierarchies present in your dance environment, some of which may include: ➢ Teacher/Student power differentials and generational differences

➢ Varied student levels, experiences, and techniques

➢ Modern/Ballet binary

➢ Prioritization of Eurocentric concert dance forms in academic spaces

➢ (Re)Prioritization of discipline collaboration (e.g., how the baile, toque, and cante work together redistributes concert dance students’ ideas of who is responsible for making the performance happen)

➢ Use of the space and where/how dancers move in the space (e.g., who is going first and last, where dancers are positioned in relation to one another, and their proximity to the teacher or musicians)

___________________________________________________________

Socialization ❖ Partner work encourages a connection between students to dance and see across differences—negotiating eye contact, careful listening, and responding to one another’s bodies for the dance to actualize. ❖ Socialization challenges Western concert dance values, causing a shift:

➢ competitive→ collaborative

➢ independent→ interdependent

➢ product→ process

___________________________________________________________

Visibility ❖ Raise awareness and share the value of folk dance in academia by encouraging the institution to engage and acknowledge the community practice that is being developed in the classroom: ➢ Invite colleagues and peers for open studio showings.

➢ Organize a performance (e.g., flash mob) that permeates the dance building hallways, corridors, and lobbies.

➢ Collaborate with local practitioners and dance groups, visiting, learning, and performing in one another’s spaces.

❖ Recognize the pride that students feel when sharing their learning experiences with others.

___________________________________________________________

Context/ Connection

❖ Make time in every class for the historical and cultural context of the folk dance. ❖ Use multimodal resources to diversify how students consider the contexts (e.g., visuals, videos, texts, pláticas, etc.).

❖ Connect students’ prior (dance) experience and contemporary (dance) studies to folk dance practice.

___________________________________________________________

Agency/ Autonomy

❖ Provide moments in the dance for students to explore the contribution of their unique voices and movement expression. ❖ Underscore the value in students’ personal interpretation of and contribution to the work.

❖ Invite students to make choices within the dance through improvisational practices (e.g., in Sevillanas, which copla they want to dance and with whom they will partner).

___________________________________________________________

Structure/ Space

❖ Acknowledge how the space has been built and what it has been built for (e.g., land acknowledgments, pláticas on the significance of dances’ geopolitical and sociocultural emergence and migrations, etc.). ❖ Consider how the use of space will encourage community and dissolve hierarchies (e.g., circles, facing away from the mirror, facing partners, and rotating line leaders).

❖ Build a series of rituals in the class structure that prioritize:

➢ The participants as human (e.g., check in on how folks are doing at the top of the class and make intentional check-in/reflection moments throughout the class).

➢ Time for practice and repetition of class material (e.g., castanet drills, zapateado, and pasos básicos).

➢ Social and improvisation practice of the dance (e.g., dancing, singing, and performing palmas for the Sevillanas with a partner and/or with the class as a whole).

___________________________________________________________

Kiri Avelar, MFA (she/ella), is a fronteriza artist-scholar and educator from the U.S./Mexico borderlands of El Paso, Texas/Cd. Juárez, Chihuahua. A former Jerome Robbins Dance Division Research Fellow for the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and NYU Teaching Fellow for the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, her work is anchored in Chicana/Latina feminist epistemologies, border(lands) studies, and interdisciplinary frameworks. Following her 11-year tenure with Ballet Hispánico in New York City as a teaching artist, dance faculty, choreographer, performing artist, and Deputy School Director, she is currently an Assistant Professor of Dance at the University of Utah and pursuing her doctorate in Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies as a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Roxanne Gray, BA (she/her), is a Tejana Salt Lake City-based independent choreographer, performer, teaching artist, and curator. She is a Modern Dance MFA Candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant at the University of Utah. Her creative research centers around the borderland experience, exploring Folklórico and modern dance practices. In her classroom and community, she works to build community through collaborative structures while exploring the diversity of identity through curated experiences. She is also the Founder, Director, and Curator of 801 Salon, a nonprofit multidisciplinary arts and performance series in Salt Lake City.

Endnotes

1 For reading on decolonizing dance curriculum and pedagogy in higher education and transforming the academy, see Delgado Bernal1998; Monroe2011; McCarthy-Brown 2014; Mabingo 2015; Amin 2016; Delgado Bernal and Alemán 2017; Delgado Bernal 2020.

2 See Gloria Anzaldúa’s conceptualization of the choque as cultural collision in Borderlands/La frontera: The New Mestiza, 1987.

3 My Ballet Hispánico teaching colegas in the Spanish Dance program included Mary Baird, Franchesca Marisol Cabrera, Maria Gabriela Estrada, Gabriela Granados, Yvonne Gutierrez, Liliana Morales, Jared Newman, Sandra Rivera, JoDe Romano, and Bernard Schaller.

4 Our notion of embodied teaching genealogies builds on Natalie Cisneros’ conceptualization of “embodied genealogies” in Embodied Genealogies: Anzaldúa, Nietzsche, and Diverse Epistemic Practice, 2019.

5 Our units were based off the Ballet Hispánico pre-professional curriculum, which introduces students to Spanish Dance through the study of Folklore (including the Sevillanas), Flamenco, Danza Estilizada, and Escuela Bolera.

6 For further reading on Danza Estilizada see García Morillo 1997 and Rivera 2021.

7 For reading on culturally relevant and responsive teaching see Ladson-Billings 1995; Gay 2000; Hammond 2015; McCarthy-Brown 2017.

8 Pláticas loosely translated can mean “informal conversations.” It is also a progressive academic methodology that contributes to personal and community healing and serves as a crucial space of theorization. For further reading see Hartley 2010; Guajardo and Guajardo 2013; Fierros and Delgado Bernal 2016; Morales et. al. 2023.

9 Our class sources included García Morillo 1997; Huidobro and Palacios 2016; Vitucci and Gioia 2003; Murga Castro 2022; Rivera 2021; Ballet Hispánico, www.ballethispanico.org.

10 For reading on pedagogies and ethics of care see Noddings 1984; Owens and Ennis 2005; Assmann et al. 2016; Motta and Bennett 2018.

11 To see another teaching approach that prioritizes cultural contextualization of Hispanic dance and music, see Espino-Bravo and English 2023.

12 Our evolving teaching practice is greatly inspired by liberatory and justice frameworks, including Emergent Strategy. For reading on Emergent Strategy see brown 2017; Buono and Davis 2022.

13 We recognize that this term “universal unfamiliar” is not perfect, it is only our first attempt at putting language to something we have explored in our pedagogy. We are trying to get to the idea of students connecting over a shared new experience together. We continue to think about this terminology as our pedagogy develops while teaching folk dance to concert-trained dancers.”

Works Cited

Amin, Takiyah Nur. 2016. Beyond Hierarchy: Reimagining African Diaspora Dance in Higher Education Curricula. The Black Scholar. 46.1: 15-26.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Assmann, Hugo, Leonardo Boff, and Alberto Villalba. 2016. Placer y ternura en la educación : hacia una sociedad aprendiente. Madrid: Narcea Ediciones.

brown, adrienne maree. 2017. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press.

Buono, Alexia and Crystal U. Davis. 2022. Creating Liberatory Possibilities Together: Reculturing Dance Teacher Certification Through Emergent Strategy. Journal of Dance Education. 22.3: 144-52.

Cisneros, Natalie. 2019. Embodied Genealogies: Anzaldúa, Nietzsche, and Diverse Epistemic Practice. Theories of the Flesh: Latinx and Latin American Feminisms, Transformation, and Resistance, Studies in Feminist Philosophy. New York: Oxford Academic.

Delgado Bernal, Dolores and Enrique Alemán. 2017. Transforming Educational Pathways for Chicana/o Students: A Critical Race Feminista Praxis. New York: Teachers College Press.

Delgado Bernal, Dolores. 2020. Disrupting Epistemological Boundaries: Reflections on Feminista Methodological and Pedagogical Interventions. Aztlán. 45.1: 155-70.

Delgado Bernal, Dolores. 1998. Using a Chicana Feminist Epistemology in Educational Research. Harvard Educational Review. 68.4: 55-81.

Espino-Bravo, Chita and Nicole English. 2023. Teaching Hispanic Culture, Diversity, and Tolerance through Hispanic Dances and Music: Two Approaches for Flamenco & Caribbean Dances. La Madrugá. 20.1, 10.6018/flamenco.553181.

Fierros, Cindy O. and Dolores Delgado Bernal. 2016. VAMOS A PLATICAR: The Contours of Pláticas as Chicana/Latina Feminist Methodology. Chicana/Latina Studies. 15.2: 98-121.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: Herder and Herder.

García Morillo, Juan. 1997. Mariemma : mis caminos a través de la danza. Madrid: Sociedad General de Autores y Editores.

Gay, Geneva. 2000. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Guajardo, Francisco and Miguel Guajardo. 2013. The Power of Plática. Reflections. 13.1.

Hammond, Zaretta. 2015. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, a SAGE Company.

Hartley, George. 2010. The Curandera of Conquest: Gloria Anzaldúa’s Decolonial Remedy. Aztlán. 35.1: 13-61.

Huidobro, Azucena and Mercedes Palacios. 2016. Bailando un tesoro. El libro del Ballet Nacional de España para niños. Instituto Nacional de las Artes Escénicas y de la Música (INAEM).

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1995. Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal. 32.3: 46-91.

Mabingo, Alfdaniels. 2015. Decolonizing Dance Pedagogy: Application of Pedagogies of Ugandan Traditional Dances in Formal Dance Education. Journal of Dance Education. 15.4: 131-41.

McCarthy-Brown, Nyama. 2017. Dance Pedagogy for a Diverse World: Culturally Relevant Teaching in Theory, Research and Practice. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

—. 2014. Decolonizing Dance Curriculum in Higher Education: One Credit at a Time. Journal of Dance Education. 14.4: 125-29.

Medina, Victoria and Alfdaniels Mabingo. 2022. Teaching Latinx Dances in Multicultural Environments: Pedagogic Acculturations of Latino Dance Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Dance Education, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2022.2091140.

Monroe, Raquel L. 2011. ‘I Don’t Want to Do African . . . What About My Technique?:’ Transforming Dancing Places into Spaces in the Academy. The Journal of Pan African Studies. 4.6: 38-55.

Morales, Socorro, Alma Itzé Flores, Tanya J. Gaxiola Serrano, and Dolores Delgado Bernal. 2023. Feminista Pláticas as a Methodological Disruption: Drawing upon Embodied Knowledge, Vulnerability, Healing, and Resistance. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 36.9: 1631-43.

Motta, Sarah C. and Anna Bennett. 2018. Pedagogies of Care, Care-Full Epistemological Practice and “Other” Caring Subjectivities in Enabling Education. Teaching in Higher Education. 23.5: 631-46.

Murga Castro, Idoia. 2022. Antonia Mercé ‘La Argentina’ in the Philippines: Spanish Dance and Colonial Gesture. Dance Research Journal. 54.3: 45-67.

Noddings, Nel. 1984. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Owens, Lynne M. and Catherine D. Ennis. 2005. The Ethic of Care in Teaching: An Overview of Supportive Literature. Quest (National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education). 57.4: 392-425.

Rivera, Sandra. 2021. Spanish Dance in New York City’s Puerto Rican Community. Dance Index. 12.2.

Vitucci, Matteo Marcellus and Louis Gioia. 2003. The Language of Spanish Dance : A Dictionary and Reference Manual. 2nd ed. Hightstown, NJ: Princeton Book Co.