The Black Diaspora Quilt History Project logo and all other images are courtesy of the authors or Michigan State University Museum.

Numerous people have acknowledged the importance of quiltmaking within the African American experience. Zora Neale Hurston, who closely examined Black vernacular cultural traditions, included references to quilts in her folklore-infused writing. Alice Walker (1973) wrote a well-known short story focused on quilting, and bell hooks (2008) explored how the work of African American quiltmakers conveyed historical experiences, memories, and aesthetics. The historian Darlene Clark Hine stated that “Quilts are often the only physical evidence or historical testament revealing aspects of the inner lives and creative spirits of many otherwise obscure and unknown Black women. But the quilt, like any other document, needs to be interpreted and analyzed to fully appreciate its significance in the history of African Americans, and, in particular, African American women’s cultural history” (Hine 1998, 13). The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich said that the quilts of the African American artist Harriet Power aid us in “understanding contradictory ideas about race, gender, and modernity in the late nineteenth-century and for exploring the place of African Americans in the twentieth century quilt revival” (Ulrich 2011, 85). The folklorist and photojournalist Roland Freeman recognized the individuals and processes involved in making, using, and preserving African American quilts as a “communion of spirits” and that quilts have the power “to create a virtual web of connections—individual, generational, professional, physical, spiritual, cultural, and historical” (Freeman 1996, xv). His efforts distinguished a wide range of styles, intents, and learning and sought to answer “what it means that so many African Americans, across so large an area, are involved with quilting. What is it about quilting that is so important to our culture?” (xviii).

The importance of storytelling in African American quilt heritage is critical to understanding the context in which these objects were and are created and the meaning this art has for the maker, their communities, and wider audiences. Quilts made by African American artists have been overlooked and misinterpreted by those who do not have access to the associated stories or knowledge about the contexts in which they were created. Thus, it is critical to collect and make accessible not only images and physical data on quilts, but also the stories of those who made and used them.

A new resource, the Black Diaspora Quilt History Project (BDQHP), aims to preserve a body of data of this important traditional expressive art in its myriad forms and to make that data freely accessible for teaching and research. The BDQHP is an intentional effort to digitally gather primary and secondary sources on African American, African, and African Diaspora quilt history drawn from geographically dispersed public and private collections. This data is then being added to a BDQHP hub in the Quilt Index, an international humanities project based at Matrix: Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences at Michigan State University.

African American Quilts in Museums, Archives, and Documentation Projects

Museums, through their collecting practices, exhibitions, and educational programs, are one of the main access points for public information about quiltmaking. Despite the nearly ubiquitous presence of quilts in museums in the United States, collecting practices have largely failed to include work of African American, African, or African Diaspora quilters. One exception includes the exhibition in 2002 of quilts made by African American women living in Gee’s Bend, Alabama. It proved pivotal in prompting some museums to collect African American quilts. The Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition opened first at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and then traveled to other major museums, including the Whitney Museum in New York City, where it was met with enormous positive critical and popular acclaim (Kimmelman 2002). There is no doubt that this Gee’s Bend exhibition broke ground in showing the power of quilts made by African Americans presented as art pieces while simultaneously revealing the stories of the people and communities who made them. Although traveling exhibitions of these quilts increased public interest and knowledge about African American quilting traditions, they notably featured only one style of African American quilting particular to the quilters of Gee’s Bend and did not allude to the diversity of techniques, content, and aesthetics of historic and contemporary work by other African American quilt artists. Despite an increase in the number of museums that collect African American quilts as well as more publications on African American quilts, knowledge about this important traditional expressive art in its myriad forms across the country is minimally accessible for research and teaching.

Afro-American Women and Quilts, Cuesta’s Sampler Cuesta Benberry, Annette Ammen, Lois Mueller, and the Kinloch Community Center Ladies, St. Louis, Missouri, 1979. Collection of Michigan State University Museum acc.#2008:119.1, https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=fullrec&kid=12-8-5240.

Use this image and the BDQHP archive description to learn about some of the many traditions of African American quiltmaking.

Each block is different and signifies something of importance in African American women’s quiltmaking experiences.

From left to right, top row:

- A red and white pieced block with diamonds and a red center square; (Note: this block was from an Arkansas woman, formerly a neighbor).

- A block replicated from Harriet Powers’ “Bible” quilt in applique, featuring Jesus’ baptism, two figures and the Holy spirit symbolized by an applique dove; (Note: the original quilt is in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.)

- A block in dark blue and white with reverse applique; (Note: This design was made by an enslaved person from North Carolina).

Second row, left to right:

- A pieced and appliqued flower in navy blue, teal and orange with a green stem; (This pattern was taken from the Freedom Quilting Bee, forerunners of today’s Gee’s Bend Quilters).

- A “Variable Star” block out of red and white cotton with the following poem (sent by Jinny Beyer from The Liberator) inked in the center: Mother! When around your child You clasp your arms in love And when with grateful joy You raise to God above— Your eyes, Think of the Negro mother; When her child is torn away— Sold for a little slave–oh, then, For that mother, Pray!

- A tulip applique block in green, purple, and red; (Note: This pattern was from the WPA project that collected quilt designs).

Third row, left to right.

- “Buzzard’s Roost” (Note: this block was found in a former slave cabin) A pieced block in brown and white with an eagle quilted in the center;

- A flowering vine in applique with green leaves and red, yellow and blue blooms; (A Nancy Cabot design) and

- “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul” block with print navy fabric used with white. (Note: Florence Peto used this block in the end paper of her book and mentioned that an enslaved person had made this quilt).

Fourth row, left to right.

- “Lady’s Shoe” applique in solid red and white (This is a replica of a block from a Benberry family quilt);

- A “brick” quilt in various fabrics cut in strips of varying lengths;

- An African woman depicted in applique with a clay pot.

All text adapted from the primary source description in the Quilt Index.

Another major source of data about quilt history comes from regional grassroots quilt documentation projects that began in the mid-1980s. They were initiated and led primarily by quilt scholars or members of state and regional quilt guilds who wanted to make sure that information about this art form, one created primarily by women, was recorded. These projects were geographically circumscribed by county, state or province, or country; some were conducted over a set period of time and have been concluded, others are ongoing, and new ones are regularly initiated. A basic format involves project leaders encouraging makers and owners to bring their quilts into central community locations (museums, libraries, senior centers, etc.) on “Quilt Days.” Volunteers measure and photograph the quilts; describe physical features; and collect biographical information on the quiltmaker and social history of the quilt, including its production, ownership, purpose, function, and any affiliated stories. The collected information is recorded on standardized survey or inventory forms and sometimes the stories about the quilt and its maker are audio or video recorded. Shelly Zegart, one of the founders of the Kentucky Quilt Project, observes that these projects collectively form “the largest grassroots movement in the decorative arts in the last half of the 20th century. More than 200,000 quilts have been documented at more than 2,000 ‘Quilt Days’ and additional projects are starting every year” (Zegart n.d.). Notably, very few of these documentation projects made special efforts to document quilts made by artists of non-white descent.1

The Quilt Index: Preserving, Accessing, and Using Quilt History Data

The Quilt Index launched in 2003 as a digital humanities resource to preserve and provide access to data on geographically dispersed collections of images and stories about quilts and their makers. It began with a small portion of the records of only four state documentation projects as well as of collections at two museums.2 As funding made growth possible, the Quilt Index has inputted data from other quilt documentation projects in the U.S., New Zealand, Australia, Great Britain, and South Africa. It has also partnered with museums, archives, libraries, and individual collectors, artists, and scholars from around the world to add records from these public and private holdings. As of 2023, the Quilt Index holds over 90,000 records. To facilitate public engagement, the Index has also developed numerous features for exploring and using the Index content for research and learning. These features include tools to search, cite, compare, and contrast data as well as a submission portal for individuals to add their own quilts and stories directly to the Index. Resources added to the Quilt Index have included exhibitions, galleries, essays, bibliographies, and lesson plans.

The Need for a Black Diaspora Quilt History Project

Because this digital resource originally was built on quilt documentation projects and limited collections that rarely included the African American quilting experience, the content of the Quilt Index reflected the relative absence of data from these contributors on this important realm of material culture heritage. A 2000 study estimated that there were over one million African American quilters and that one in twenty U.S. quilters is African American (Hicks 2003, 10). Yet, out of nearly 90,000 records in the Quilt Index as of the end of 2022, less than 1 percent of the content pertains to African American, African, and African Diaspora quiltmaking. Thus, the BDQHP was initiated to redress this absence of data and to include quilts and stories that reflect the diversity within as well as linkages among quiltmaking practices of African American, African, and African Diaspora communities.

With support from a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, during the period 2022–2024 the BDQHP will add to the Quilt Index thousands of records that document Black quilt history.3 As BDQHP director and co-director, we are working with other members of the Quilt Index team to implement strategies to reach and engage more diverse audiences who can add their data to the Index as well as use the existing data in their research, creative, and teaching activities. We began by conducting an Inclusivity Audit of the standardized form historically used in the quilt documentation projects and amended terminology and imagery that would be more inclusive. Rather than relying only on these forms to gather data on quilts, quiltmakers, and the technical and social history of quilts, project staff are turning directly to artists and collectors to ask what stories, associated documentation (photographs, oral histories, blogs, websites), and related ephemera (study sketches, patterns, exhibition posters, diary accounts) they want digitally preserved and then working closely with them to ensure preservation in the Quilt Index. This direct work with Black quilters to determine their needs is essential to provide responsive, meaningful, and comprehensive documentation of the histories, stories, and legacies of Black quilt artists.

By focusing on building the body of data, the BDQHP provides a means for considering these quilts as visual documents and to read and listen to their associated stories. We hope that this will, in turn, foster questioning, exploration, and understanding of the history and experiences of Black artists and communities. In this time of growing recognition that #BlackLivesMatter, this project offers primary data, resources, and tools to assist individuals in acquiring knowledge about Black quilt artists and their quilts, engaging in dialogues about difficult issues, and finding inspiration and hope in the stories and histories illustrated by this art form. It will create access to data and resources that, as Carolyn Mazloomi, founder of the Women of Color Quilters Network (WCQN) and an NEA National Heritage Fellow, notes allow individuals to use African American quilts “as an aspiring solution to the problem of educating the general population about the ascendant influence of African-American culture on the American cultural landscape.” (Mazloomi 2021, 5)

The Black Diaspora Quilt History Project: Resources for Learning and Teaching

The Quilt Index is currently a resource that allows for the exploration and discoveries of objects and stories related to quilts and quiltmakers. To facilitate deeper engagement with these materials, the BDQHP is adding to the Quilt Index website secondary resources (essays, galleries, exhibitions, and U.S. standards-based lesson plans) related to Black quilters and their quilts. Content specialists and educators will enhance scholarly and educational use of digital resources by diverse audiences. For example, Furman designed educational resources and curated experiences to center womanist literacies of reflection and care. These instructional tools invite learners to consider their own lived experiences and sociopolitical realities, using literacies rooted in African American storytelling traditions and contemporary wellness praxis such as journaling and dialogue to engage meaningfully with Black quilters’ stories, quilts, and other ephemera within the Quilt Index collection.

Learning Resources with Quilts from Black Diaspora Artists

Furman is also developing models for engaging teachers and students in using both the Quilt Index and physical museum collections and archives. As an example, in guided visits to the MSU Museum, students intimately experience a curated collection of quilts made by Black quilters throughout the Diaspora as well as photographs, patterns, and other materials that documented their experiences. Physical duplicates of the original materials were made for in-class use and scanned for remote use on the Quilt Index website.4 Images and stories of the quilts are also in the Index. During sessions with students, Furman uses reflection questions to guide students through their conceptualizations of what quilting is, who quilts, and the speculative significance of quilts within the lived realities of quiltmakers. In each hands-on guided conversation, students learn popular quilt terminology and a variety of quilt styles and construction techniques. Learners are encouraged to make personal connections with the quiltmakers and their quilts, inviting a deeper understanding of the lived implications of quilts and quilt praxis. Students are prompted to ask and answer questions rooted in curiosity and wonder as a means of exploring and imagining realities informed by Black folks’ material culture and quiltmaking methodologies.

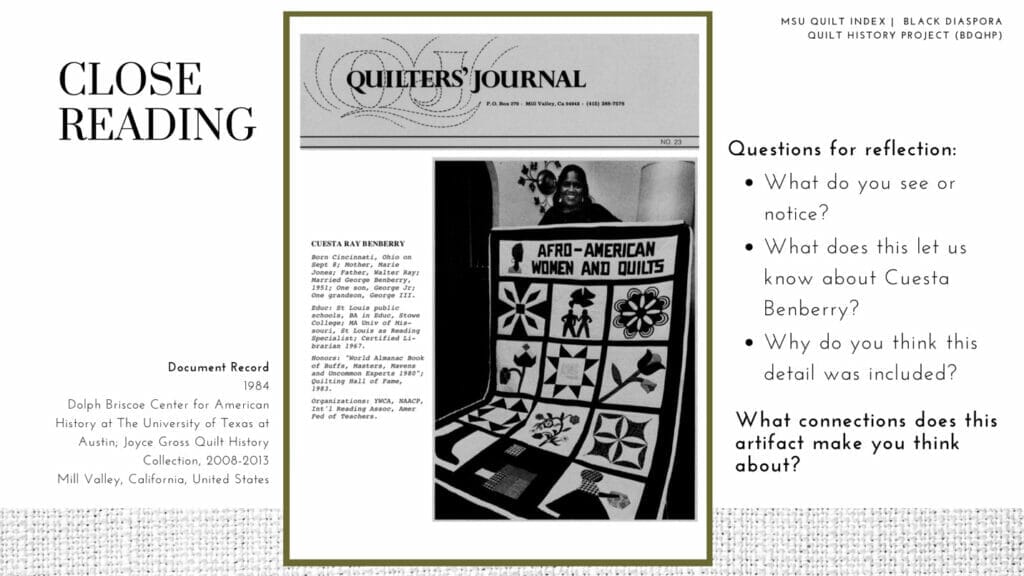

Sample page from the BDQHP Cuesta Benberry lesson plan slideshow (Furman 2023).

Learning Resources with the Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Research Collection

Furman designed a series of tools to increase learning about Cuesta Benberry—a renowned African American quilt scholar, writer, researcher, and pattern collector—and her collection of quilts, patterns, and other quilt-related ephemera (exhibition catalogs, event flyers, notes, cards, quilt and sewing patterns) at the MSU Museum.5 The activities and resources guide learners through intentional engagements with a curated sampling of artifacts from the Benberry collection that connect to the overall aims of the BDQHP.

The learning activities engaging with materials from Benberry’s collection center around using and developing visual communication skills, via multiple close readings of objects. Reflection questions generate dialogue and deep thinking about individual collection pieces. The discussion questions prompt critical inquiry of archival and museum praxis as well as the individual artifacts themselves. Learners are invited to discuss questions such as Whose histories and/or stories are embodied within the archival and museum materials we explored? Who is excluded? Why is it important to know and/or share these stories? Learners are similarly guided through considering implications of these artifacts within learners’ current lived realities, as well as ways these artifacts might inform how they think about and engage with one another and the natural world, both now and in the future.

To deepen learners’ conceptualizations of the lived implications of archival and museum collections as well as their own experience engaging with these materials, they are invited to consider the ways they collect information about their lives and legacies and to consider the ways this may change in the future, depending on their unique interests, values, and ethical commitments. As learners engage with these questions through journaling or group dialogue, they are invited to root their reflections in their personal engagements with Benberry’s life and legacy as well as the stories, material artifacts, and quilt methodologies of other Black quilters throughout the Diaspora.

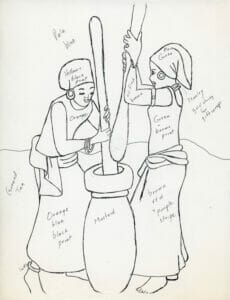

Women working together pattern from Cuesta Benberry’s Archive.

Curriculum Guide Learning Resource

Furman also authored a BDQHP Black Quilts Curriculum Guide. It provides a robust compilation of photographs and narrative information about a curated collection of quilts made by Black quiltmakers throughout the Diaspora; information about five selected African American quilt artists; prompts for reflection and creative expression; and lists of basic quilt terms, artists, scholarship, and groups. A YouTube tutorial sharing useful tips on locating and using African, African American, and African Diaspora resources in the Quilt Index is forthcoming. Together, these resources are expected to increase awareness of, appreciation for, and engagement with Black Diaspora quilt history.

Conclusion

One of the most remarkable details about quilts is that they are deeply connected to the human experience; the materials, methods of construction, and forms and styles of quilts richly embody the stories, legacies, and sociopolitical realities of the people who make them. Importantly, quilts created by artists of African American, African, and African Diaspora communities must not be reduced to the physical artifacts, which can be easily essentialized and commodified. Instead, it is important to engage with quilts made by artists in Black Diaspora communities with their stories of quiltmakers, their literacies, and their cultural traditions at the forefront. This is an explicit goal of the BDQHP and an increasing commitment of the Quilt Index.

Another goal of the BDQHP is to make accessible African American, African, and African Diaspora quilts, quilt-related ephemera, and stories of quiltmakers for meaningful research and teaching engagements. As material artifacts deeply rooted in cultural praxis and individual self-expression, critical learning engagements with quilts and quiltmakers have the potential to illuminate intimate realities of a range of topics and themes. Moreover, the interconnected nature of identity-informed literacies such as quilting, storytelling, meaning-making, and song, namely within African American traditions of quiltmaking, offers a particularly unique and multilayered foundation for deep interdisciplinary learning engagements.

Cuesta Benberry, illustration by Liv Furman.

Marsha MacDowell, PhD, (she/her) is a professor and curator at Michigan State University. She serves as Director of the Michigan Traditional Arts Program and of the Quilt Index. She has published widely on traditional material culture (with a strong emphasis on women’s work), on folk arts and education, and community-engaged museum practices. Her work is, by design and philosophy, developed in collaboration with representatives of the communities affiliated with the foci of projects. ORCID 0000-0003-3614-6514.

Olivia “Liv” Furman, PhD, (they/them) is a Black non-binary womanist artist//educator//researcher at Michigan State University currently exploring the significance of engaging culturally informed literacies of dreaming, journaling, storytelling, and the arts within conceptualizations and practice of liberatory teaching, learning, and research. Their primary mediums include multimedia and digital collage, ceramics, quilting, and the written and spoken word. Liv is also an avid gardener, skater, singer, musician, and yoga apprentice.

Both authors work at Michigan State University, situated on the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg–the Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples.

Endnotes

1 “White” is used here to clarify that the stories and images of BIPOC quilts were rarely documented.

2 Read more about the Quilt Index history here: https://quiltindex.org/about/our-history.

3 During the grant period June 2022–June 2024, the BDQHP aims to add collections of 1) 5,000 images and data on quilts and quilt artists and stories; at minimum 100 oral histories; and at minimum 100 pieces of ephemera drawn from the 20 American and South African museums and libraries identified as containing the majority of public holdings of African and African American quilts and quilt history or having significant individual quilts; 2) the records from the Washington State African American Quilt Documentation Project (the only state quilt documentation project focused on African American quilting); 3) a body of images, data, and ephemera from the private collections of six contemporary quilt artists and from members of the Women of Color Quilters Network (the largest national quilt artist organization) and the Great Lakes African American Quilters Network (one of the largest regional African American quilt artist organizations); and 4) selections of images, data, media, and ephemera from the privately held research collections of scholars of Liberian, Indian African Siddi, and Egyptian quilt history. Included will be materials from some of the most important historical chroniclers and scholars on this realm of quiltmaking, such as Roland Freeman, Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi, Dr. Gladys-Marie Fry, Dr. Stephanie Beck Cohen, Eli Leon, Kyra Hicks, and Cuesta Benberry.

4 See Olivia Furman, Exploring the Life & Legacy of Cuesta Benberry: Artifacts from the Archive, Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=lessons kid=62-186-51; Women Working Together Pattern, Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=publications&kid=62-186-49.

5 See the Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Research Collection, Quilt Index, Olivia Furman, Exploring the Life & Legacy of Cuesta Benberry: Artifacts from the Archive, Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=lessons&kid=62-186-51.

For more information and resources related to the BDQHP visit https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=docprojects&kid=62-185-1. For general information about quilts and quilt-related resources explore the Quilt Index website at https://quiltindex.org.

Works Cited

Black Diaspora Quilt History Project. Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=docprojects&kid=62-185-1.

Hicks, Kyra E. 2003. Black Threads: An African American Quilting Sourcebook. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Hine, Darlene Clark. 1998. Quilts and African-American Women’s Cultural History. In African American Quiltmaking in Michigan, ed. Marsha MacDowell. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 13–17.

hooks, bell. 2008. Belonging: A Culture of Place. Nashville: Routledge Hill Press.

Freeman, Roland. 1996. A Communion of the Spirits: African American Quilters, Preservers, and Their Stories. Nashville: Routledge Hill Press, xv–xviii.

Furman, Olivia. 2023. Exploring the Life & Legacy of Cuesta Benberry: Artifacts from the Archive. Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=lessons&kid=62-186-51.

Kimmelman, Michael. 2002. Jazzy Geometry, Cool Quilters.. New York Times, November 29, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/29/arts/art-review-jazzy-geometry-cool-quilters.html.

Mazloomi, Carolyn. 2021. Quiltmaking for Social Justice. In We Are the Story: A Visual Response to Racism. West Chester, OH: Paper Moon Publishing.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. 2011. A Quilt Unlike Any Other: Rediscovering the Work of Harriet Powers. In Writing Women’s History: A Tribute to Anne Firor Scott, ed. Elizabeth Anne Payne. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 82-116.

Walker, Alice. 1973. Everyday Use. Harper’s, https://harpers.org/archive/1973/04/everyday-use.

Worrall, Mary. The Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Research Collection. Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=specialcolls&kid=12-91-465.

Zegart, Shelly. n.d. Since Kentucky: Surveying State Quilts. Quilt Index, https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=essays&kid=8-109-1.

URLs

Black Diaspora Quilt History Project, Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=docprojects&kid=62-185-1

The Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org

Afro-American Women and Quilts https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=fullrec&kid=12-8-5240

“Essays,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/resources/essays

“Galleries,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/resources/galleries

“Exhibits,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/resources/exhibits

“Lesson Plans,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/resources/lesson-plans

The Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Research Collection, Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=specialcolls&kid=12-91-465

Olivia Furman, “Black Quilts Curriculum Guide,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=publications&kid=62-186-61

“Resources,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/resources

Olivia Furman, “Exploring the Life & Legacy of Cuesta Benberry: Artifacts from the Archive,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org/view/?type=lessons&kid=62-186-51

“Women Working Together Pattern,” Quilt Index https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=publications&kid=62-186-49