Delia Zapata Olivella, daughter, mother, sister, friend, bruja…. She was an Afro-Colombian woman born in 1926 in Santa Cruz de Lorica and lived her childhood in Cartagena, Colombia. Delia Zapata Olivella was a renowned dancer, artist, teacher, activist, folklorist, and scholar recognized by many in Colombia as “la madre del folclor colombiano” (Colombia’s folklore foremother). She gained such a nickname for her pioneering contributions to the research of Colombian cultural traditions and practices, including her use of ethnography; the introduction of audio-recording technologies to rural areas that had not been documented before; her activist practices to make visible Black and Indigenous populations in urban spaces; the use of dance notation to understand embodied practices in the country; and creation of the first Black folkloric dance company in Colombia. On top of her innovations, Delia Zapata Olivella published several articles in Spanish and one in English. However, despite the tangible evidence of her intellectual contributions—present in archives and oral histories—music scholars in Colombia, Latin America, or the United States rarely cite her work, and historiographical accounts of the field of music research only briefly mentioned her. Thus, listening for Delia Zapata Olivella is key for decentering the dominant masculine and the white gaze that have shaped the narratives about the development of music research. Listening for Delia Zapata Olivella sheds light into a significant part of history that has been ignored and unveils the role and presence of women in the establishment of ethnomusicology as a discipline.

The public discourse in Colombia positions Delia Zapata Olivella in a space of ambiguity that celebrates her artistry and activism while ignoring her intellectual contributions, particularly in music research. As a Black woman from the Colombian Caribbean, Delia Zapata Olivella endured multiple forms of discrimination. While resisting oppression she created new possible ways to exist in a country that did not recognize Black and Indigenous peoples as citizens. A framework that goes beyond the binaries of oppressed and oppressor is needed to understand how minoritized people like her shaped the world, and to challenge dominant narratives that ignore them. Thus, I find in the term re-existence—where “living itself is political”— a possibility for framing Delia Zapata Olivella’s life in music studies historiography. The Colombian artist and cultural studies scholar Adolfo Albán Achinte further defines re-existence as:

Re-existencia es recrear la vida. Es estarse inventando la vida no solo para enfrentarse a las estructuras de poder, sino para auto-reconocerse en la alegría y la celebración de la existencia […] Re-existencia, es el compromiso por el mantenimiento y la reproducción de la existencia en condiciones de dignidad en procesos de transformación de la sociedad. Entonces, el asunto de vivir se vuelve politico.1 (Alban 2015)

To amplify Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice as a scholar and activist, I use relational and multimodal archival exploration with formats that range from the written to the audio-visual. Through this framework of re-existence and relationality I recognize how Delia Zapata Olivella lived a full life, not only resisting oppressions but also creating new possible worlds.2 Her research, activism, and artistry shed light into the multiple ways women—particularly Black women—articulate their intellectual voices and enunciate their existence amidst oppression. This articulation comes after the creation of complex texts that are many times not coded as scholarship, and therefore, the registers of their voice remain ignored. In this text, I want to share my path through a relational exploration of four archives—Instituto Popular de Cultura, Indiana University Archives, The Archives of Traditional Music, and Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives—that led me to listen to Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice in a different and revealing way.

I briefly narrate part of the genealogy of this project through anecdotal vignettes that explain my relationship with the archives. Then I move to specific instances when listening for Delia became a transgressive act, since it amplified other women’s voices in the archive, decentering the male gaze of the archive and challenging the dominant histories that render the labor of these women invisible.

Archival Work and the No-Methodology Approach

I was born and raised in Colombia in a middle-class family in Bogotá, the capital city of the country, where I did my bachelor’s degree in violin performance. During my undergraduate program the focus (as in many music programs) was on Western European music, hence, little was taught about Colombian traditional musical practices, genres, musicians, or researchers. Although I always had an interest in research and other musical forms, I did not learn enough about women musicians or researchers, and I never encountered the name of Delia Zapata Olivella except in reference to one of the theaters in the city where the National Symphony Orchestra used to rehearse. When I moved to the United States to pursue my graduate degrees, it was a challenge learning how to listen to women in music, which parallels the dynamics in my country, where minoritized people are continuously ignored and pushed to the margins. Not surprisingly, I was unaware of the depth and breadth of Delia Zapata Olivella’s work.

In 2018, as a final project for a graduate seminar on mobilities, I was curious to explore the collections of the U.S. ethnomusicologist George List deposited at the Archives of Traditional Music (ATM) at Indiana University. George List was on the faculty there and was also a former ATM director. He was known for his work in applied ethnomusicology and his efforts for preserving sound recordings produced in fieldwork. Among his multiple interests, List conducted research on the musical practices of people in the town of Evitar, Colombia, a work published in his monograph Music and Poetry in a Colombian Village: A Tri-Cultural Heritage (1983).

Although this was the first time I had engaged in archival research, my experience working as a graduate student for the ATM guided my research. After many hours of listening to the recordings, I learned these sound archives were related to another collection of George List materials deposited at the Indiana University Archives. After digging into 20 boxes of documents there, I decided to use a network analysis approach to start making sense of a significant set of networks that List created during his career. This formative research centered relationality and collaborations as the core of my research. Nevertheless, it is important to note that at that moment Delia Zapata Olivella’s name, although present in the archive, was not yet a name I could hear clearly.

In 2020, I engaged in a Digital Humanities project to showcase how the materials from both archives co-related, focusing on the collaboration between List and the Zapata Olivella siblings (Manuel and Delia), two Afro-Colombian scholars, artists, and activists. By this point, I started to find interesting information about Delia Zapata Olivella, and my project advisors encouraged me to follow her lead, to find out more about her. However, it was difficult to listen to her in an archive created by a white U.S. ethnomusicologist, because he was my initial interlocutor in the archive, and I understood him to be the only expert. My own engagement with List made it difficult for me to listen to Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice and to center her work. This situation confronted me with my own limitations and coloniality.3 I knew that as a researcher I needed to embrace the invitation made by Latin American decolonial scholars and activists to deconstruct my beliefs and my way of interacting with the world. Only through a critical self-examination is it possible to listen to what we have been taught is not audible and to give space in history to Black women who have paved the way for many of us. As stated by the Combahee River Collective in their Black Feminist Statement “If black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression” (Combahee River Collective 1979, 368).

Since then, I have been revisiting the archives, and each interaction has differed because we make of archives a fluid entity, with multiple afterlives. Thus, following a predetermined path in research will not suffice for amplifying Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice. I found a useful framework and tool for creating my own path to archival research in Alejandro Haber’s proposal of a no-methodology approach. Haber suggests that “[una] [m]etodología disciplinada es seguir la secuencia protocolizada de acciones para alcanzar un conocimiento, trazar el camino que se ha de seguir. No-metodología es seguir todas aquellas posibilidades que el camino olvida, que el protocolo obstruye, que el método reprime. Es conocimiento en mudanza”4 (Haber 2011, 29). Thus, to un-discipline my research method is a way to listen actively for Delia; it is a way to recognize her acts toward re-existence and to question my own paths. It is a conscious practice of listening to Black women’s voices and perspectives; it is a way to open my ears and attunement to what they have been writing, saying, singing, and performing in multiple iterations and to honor their lives—through the deconstruction of my own practice.

Challenging history requires us to think in relation to one another, to value, analyze, and understand different ways of living. To activate the archives in a relational manner is a way to amplify Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice.

Relationality in the Archives: Journaling Through Listening, Sensing, and Reading

Throughout my path, I kept track of my relationship with the archives in a listening journal. It was a space for me to learn, reflect, and deconstruct my own coloniality—from an embodied listening practice. I recorded my feelings, sensations, thoughts, and emotions and how they informed my relationship with the materials and histories that the archives yielded. Looking back to that journal, I can understand the way I was relating to the archives, the relationships I found in the archives, and how archives related to one another. I used my training as an ethnographer to interact with the archive, since I understand the archive to be a living body that is constantly transforming and that, at the same time, transforms me. I also used this space to reflect on my relationship to Delia Zapata Olivella. Why did not I pay attention to her work before? Why as a former music student had I never heard about her? Why it was harder for me (a woman from a city and from the majority demographic group–mestizos) to listen to her voice? In that journal I inscribed my understanding of the histories I was trying to unveil and the questions I was trying to answer. This process helped me form a critical perspective of my positionality as a mestiza. In what follows I delve into key examples that helped me listen in a different way.

How Everything Started

El professor George List, director del Archivo de Música Tradicional de la Universidad de Indiana, y su esposa Eva, llegaron preguntando por Delia en los ventorros que aún pululan en la barriada del Getsemaní. Alguien rescató a la pareja extraviada en la playa del Arsenal entre arrumes de carbón y racimos de bananos. Mi padre, sentado en la Puerta de su casa, los recibió cerrando el libro de lectura, acto de reverencia que concedía a los extraños. Solicitaron a la bailarina. A sus manos había llegado un programa de las presentaciones de su grupo de danzas.

-Venimos a que nos ayude a investigar el folclor musical colombiano

Mi hermana sonrió. Se electrizaba siempre que alguien pellizcaba aquella vena de su sentimiento.

-¡Comience conmigo, yo soy el folclor!

[…] Media hora después de conocerla, antes de salir a investigar con ella los cantos de los negros de Palenque, comenzó a grabar su voz, sus tonos profundos, su risa, la explosión de su silencio. Comprendió que estaba frente a un espécimen del folclor no modelado por indiferencias extrañas. El mismo le conseguiría una beca para que aprendiera con Katherine Dunhan las técnicas de la danza moderna.5 (Zapata Olivella, Manuel 1990, 324-5)

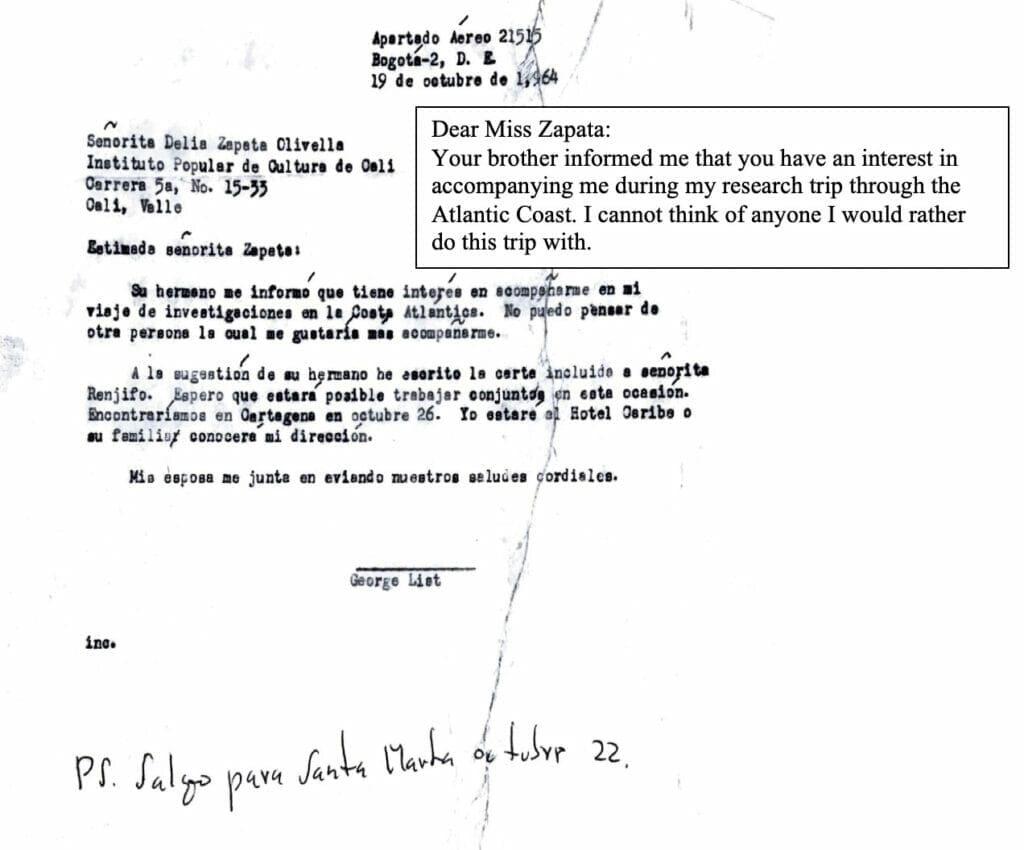

In his book Levántate Mulato, Manuel Zapata Olivella tells a fantastic story about how Delia Zapata Olivella came to work with George List. Yet the IU Archives tell a different story. The available documentation indicates that Delia’s collaboration with List followed her brother Manuel’s suggestion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. George List, October 19, 1964. George List Papers C242. Box 6. Folder “Zapata Olivella, Delia 1964.” IU Archives. Bloomington.

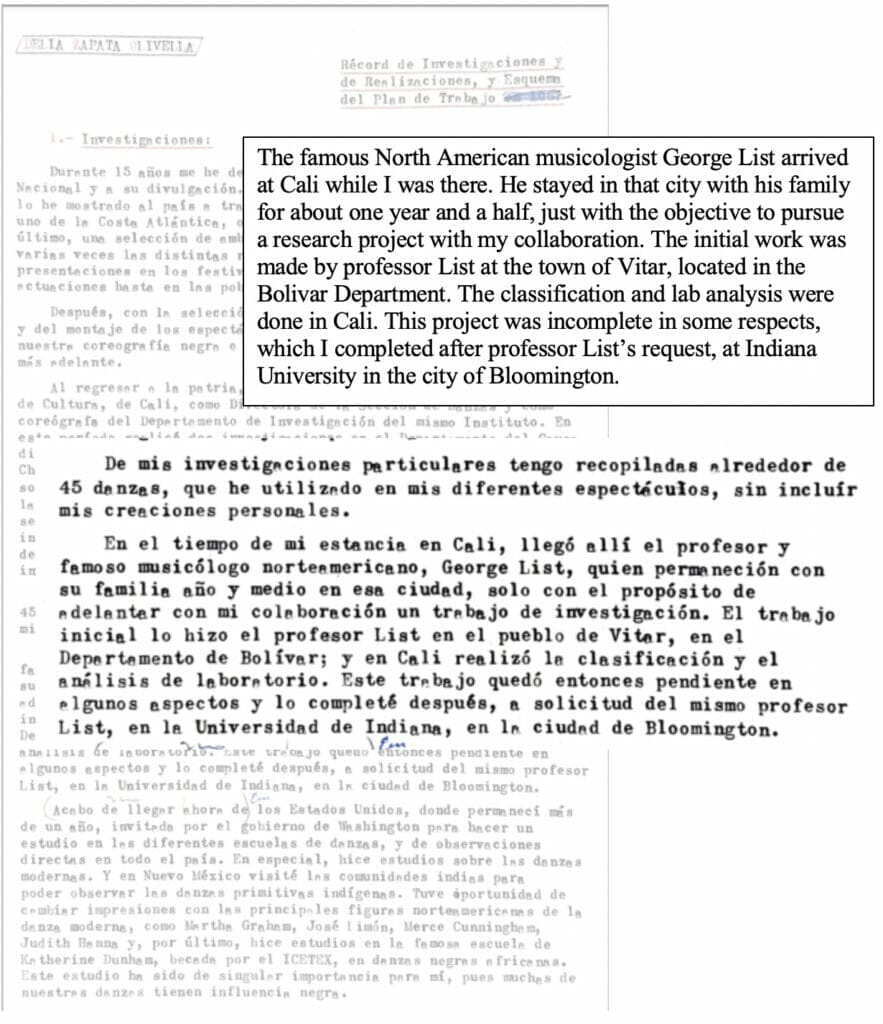

It was not until later in my research that I could access Delia Zapata Olivella’s archive, deposited at Vanderbilt University. There, I read for the first time her own voice. A set of reiterations of her autobiography and CV revealed her understanding of the situation. In one summary of her research activities, Delia Zapata Olivella indicates that the first encounter with List happened in Cali, not Cartagena, and that he was seeking for her to be a collaborator (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Delia Zapata Olivella, ca. 1967. Delia Zapata Olivella Papers, Box 30 Folder 1. Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives. Nashville, Tennessee.

These three different viewpoints of a single historical event helped me complicate the narratives that present Delia Zapata Olivella only through the gaze of her male peers. To include her voice as part of these accounts is important for contrasting narratives that have been widespread in the academic accounts of either her brother Manuel Zapata Olivella or George List.

Positioning Delia Zapata Olivella: Assistant or Adviser?

List always acknowledged Delia Zapata Olivella as a collaborator. In his book, List shows two different ways he saw and understood her role. In his prologue List indicates that she joined him “to act as [his] field assistant” (1983, xxi), while in his acknowledgments he states that “Delia Zapata was [his] first tutor in costeño life and custom” (1983, xxv). Those two brief mentions signal a dual role that he saw her accomplishing. Nevertheless, it is the prologue that readers recall since it sets the tone of what the work entails, positioning Delia Zapata Olivella as List’s assistant.

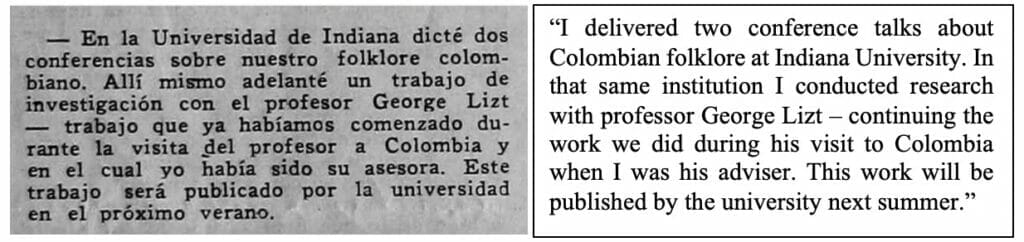

Considering that the IU Archives were presenting Delia Zapata Olivella through the lens of George List, I decided to explore other archives where her voice was central. Thus, I found an article published in 1967 in which Delia narrates her time in the U.S.; her studies with Katherine Dunham, José Limón, and others; and her collaboration with George List (Figure 3). In these texts Delia points out her contributions to List’s work and her activities at IU.

Figure 3. Excerpt from Ballet o Danza Folclórica? In Páginas de Cultura. No. 15, Revista del IPC de Cali, 1967. Taken from digital archive of Revista institucional del Instituto Popular de Cultura de Cali.

Whether she considered herself to be a “tutor,” an “adviser,” or a “consultant,” all are categories that assert her expertise as researcher, whereas the category “assistant” can easily undermine her knowledge and years of experience and hide the level of her contributions to the research. It is important to note that by the time Delia Zapata Olivella collaborated with List, she had more than ten years of experience conducting ethnographic research and had a deep knowledge of cultural practices in the region. After listening to the recordings List made on their 1964 trip and deposited at the ATM, I started noticing that Delia Zapata Olivella was shaping List’s research in multiple ways.

Translation: George List was not fluent in Spanish by the time he did his first fieldtrip, and he knew little about musical practices in the Colombian Caribbean. Delia Zapata Olivella, on the other hand, was native to the region and had spent several years researching different musical and dance traditions. Therefore, Delia Zapata Olivella acted as an interpreter for him, not only in terms of English-Caribbean Spanish but also in musical and cultural terms.

Translation: George List was not fluent in Spanish by the time he did his first fieldtrip, and he knew little about musical practices in the Colombian Caribbean. Delia Zapata Olivella, on the other hand, was native to the region and had spent several years researching different musical and dance traditions. Therefore, Delia Zapata Olivella acted as an interpreter for him, not only in terms of English-Caribbean Spanish but also in musical and cultural terms.

Silencing through her epistemic authority: Delia Zapata Olivella was not free of reproducing epistemic violence common in ethnographic practice. In this interview List was interested to learn about his interlocutors’ (Catalino Parra, Francisco Ramirez, Antonio Orozco, Jesus María Ramirez, and Enrique Alberto Sarmiento) jobs or occupations. Delia Zapata Olivella asks about how they learned their occupations but interrupts them shortly after one tried to tell some additional information.

Silencing through her epistemic authority: Delia Zapata Olivella was not free of reproducing epistemic violence common in ethnographic practice. In this interview List was interested to learn about his interlocutors’ (Catalino Parra, Francisco Ramirez, Antonio Orozco, Jesus María Ramirez, and Enrique Alberto Sarmiento) jobs or occupations. Delia Zapata Olivella asks about how they learned their occupations but interrupts them shortly after one tried to tell some additional information.

Shaping the narrative of the research: Connecting with community is an important part of the ethnographic endeavor. Delia Zapata Olivella was closely related to some of the musicians who were List’s interlocutors, since they played for her dance group. This relationship had a big impact on the information List could gather. In this interview Delia is asking Catalino Parra about the rhythms usually performed with music ensembles. At first, he did not list all the rhythms, so she intervened, asking for specific rhythms, trying to evoke their memory. The joke “traen gordo, que están comiéndose la mitad de lo que hacen”6 sets a playful, sassy tone that I associate with schoolteachers who patiently help students remember all of what they already know.

Shaping the narrative of the research: Connecting with community is an important part of the ethnographic endeavor. Delia Zapata Olivella was closely related to some of the musicians who were List’s interlocutors, since they played for her dance group. This relationship had a big impact on the information List could gather. In this interview Delia is asking Catalino Parra about the rhythms usually performed with music ensembles. At first, he did not list all the rhythms, so she intervened, asking for specific rhythms, trying to evoke their memory. The joke “traen gordo, que están comiéndose la mitad de lo que hacen”6 sets a playful, sassy tone that I associate with schoolteachers who patiently help students remember all of what they already know.

It is important to emphasize that by positioning Delia as an adviser, mentor, or tutor, I also intend to acknowledge the power differentials in her collaboration with List and their ethnographic work in territory. Understanding Delia Zapata Olivella’s re-existing in the archive opens the door for new perspectives that provide a more complete picture of this history and her history.

Amplifying Whispers: Delia Zapata Olivella and Eve Zipoura Ehrlichman

Amplifying Whispers: Delia Zapata Olivella and Eve Zipoura Ehrlichman

“I have a question” —Eve Ehrlichman’s voice

When I began my listening journey of the field recordings at the ATM, I prepared myself to search for Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice. Body and mind were attuned to listening for female voice registers. To my surprise, not until the eighth tape in a collection of 42 sound tape reels did Delia Zapata Olivella’s voice appear. Nevertheless, other women’s voices called my attention, particularly that of Eve Zipoura Ehrlichman. Eve (or Eva as Delia Zapata Olivella called her), was a pianist, pedagogue, community leader, and George List’s wife. Her voice appeared in the fourth tape of the collection in a rather timid way; her whisper led me to uncover a story of close collaboration that she had with Delia Zapata Olivella, a relationship that I was not considering before.

This recording was my first encounter with Eve. I have played it multiple times, and each time I perceived new details. The technology I used differed every time (speakers, earbuds, headphones, laptop speakers), and it was only when I used earbuds that I listened to a whisper saying, “Can I ask a question?” This whisper served as an interlude that prepared my ears and attuned my mind to understanding Eve Ehrlichman’s intellectual contributions. Her active role in the ethnographic endeavor and her labor of care—taking care of their children (Michael and Edelmira) while List and Delia Zapata Olivella traveled to smaller towns—are contributions that remain unrecognized but that enhanced List’s intellectual production.

This recording was my first encounter with Eve. I have played it multiple times, and each time I perceived new details. The technology I used differed every time (speakers, earbuds, headphones, laptop speakers), and it was only when I used earbuds that I listened to a whisper saying, “Can I ask a question?” This whisper served as an interlude that prepared my ears and attuned my mind to understanding Eve Ehrlichman’s intellectual contributions. Her active role in the ethnographic endeavor and her labor of care—taking care of their children (Michael and Edelmira) while List and Delia Zapata Olivella traveled to smaller towns—are contributions that remain unrecognized but that enhanced List’s intellectual production.

After listening to Eve, I needed to put a face to that voice, but there were no pictures or videos of her made during that trip that gave me any visual reference. It was in Delia Zapata Olivella’s collection at Vanderbilt University that I found multiple photos of her with her family. This discovery reveals the importance of relational practices in uncovering this part of history that was not registered in List’s book or his own archive.

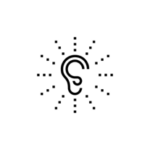

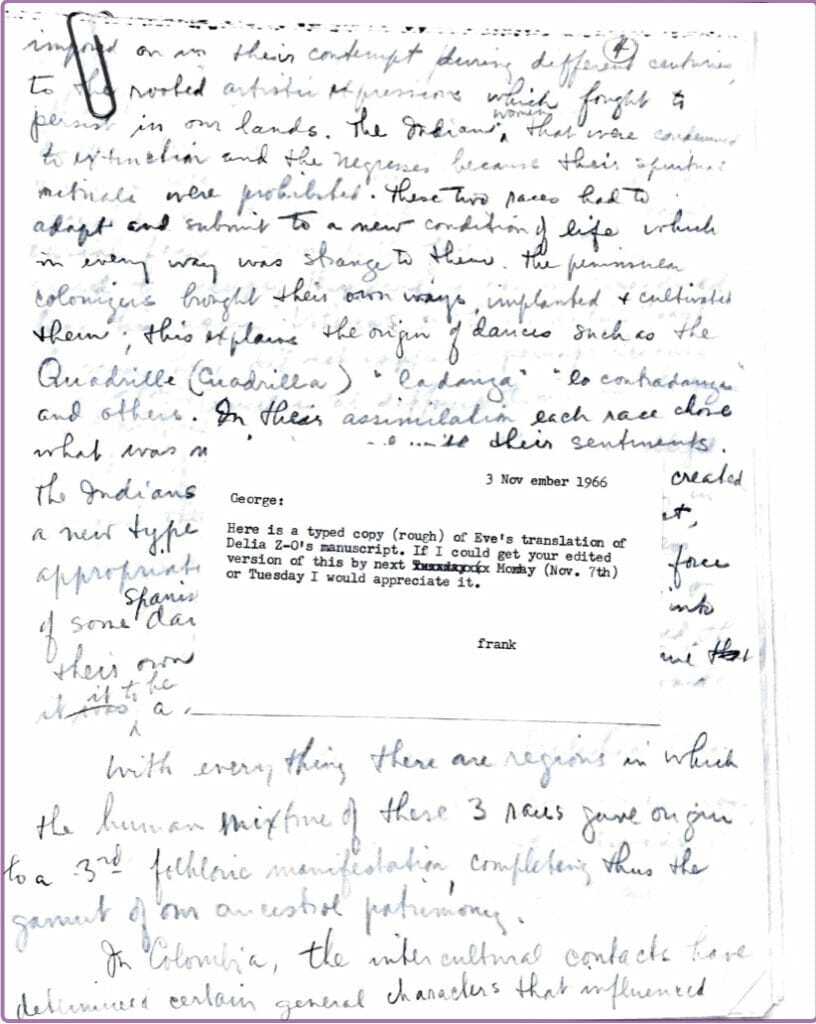

The relationship between Eve Z. Ehrlichman and Delia Zapata Olivella paved the way to foster intellectual collaborations that are not cited but are vivid in the archives. One final example I will highlight is the translation into English of an article by Delia Zapata Olivella. Experts in Delia Zapata Olivella’s scholarship, like the Colombian sociologist Carlos Valderrama, suggest that her article “An Introduction to the Folk Dances of Colombia,” published in 1967, was translated by George List (2015, 21). Nevertheless, in List’s documentation archive, I found a small note attached to a handwritten document that reveals that the translation was actually the work of Eve Z. Ehrlichman (Figure 4).

Figure 4. [Unidentified author]. November 3, 1966. George List Papers C242, Box 6 Folder “Lecture Delia Zapata Olivella 1966.” IU Archives. Bloomington, Indiana.

Delia Zapata Olivella by artist Pedro Ruiz. Centro Nacional para las Artes Delia Zapata Olivella. Photo by Amelia López López, June 27, 2023.

Amelia López López is a Colombian PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at Indiana University. Her research interests intersect the fields of Sound Studies, Latino Studies, Latin American and Caribbean Studies, and Human Rights. She actively engages with anti-racist practices, paying particular attention to the Colombian case. She examines and denounces the erasure and exclusion of Black voices amid multiculturalist discourses of Colombianidad in music studies, guided by her experience as a former graduate assistant in the Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University. Besides her academic work, Amelia is actively involved in public ethnomusicology projects including the International Student Network for Music and Sound Studies (ISNMSS). ORCID 0009-0005-5338-5690

Endnotes

- Personal Translation. [Re-existence is to re-create life. It is to be inventing life not only to confront structures of powers, but to recognize one-self from the joy and celebration of one’s existence […] it is a compromise for the sustenance and reproduction of existence in conditions of dignity amidst processes of social transformation. Thus, living itself becomes political]

- The idea of multiple worlds is explained by Arturo Escobar in his book Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible, where he demonstrates through a set of essays or ensayos how the tools and concepts developed by different social movements in the South serve as frameworks to “resist the hegemonic operation of positing one world, one real, and one possible” (2020, x). The emphasis on the plurality has been key for grassroots movements to resist and defend their territories, emphasizing that “If worlds are multiple, then the possible must also be multiple” (2020, ix).

- Following Anibal Quijano (1992), I use this term to refer to the inherent colonial violence that is present in my worldview. Quijano referred to the colonial power structures that gave shape to the idea of modernity through the creation of a power imbalance in terms of defining categories like race and class. This concept is expanded in his work on the coloniality of power.

- “A disciplined methodology is to follow a pre-determined sequence of actions dictated by a protocol that seeks to reach knowledge, it is to trace a path that is supposed to be followed. No-methodology is to follow all the possibilities that are left out from the pre-determined path, that the protocol obstructs, and that method represses. Is knowledge in movement” (Haber 2011, 29).

- Personal Translation. [Professor George List, director of the Traditional Music Archive of the University of Indiana, and his wife Eva, arrived asking for Delia in the “ventorros” (street vendors) that still swarm in the Getsemaní neighborhood. Someone rescued the lost couple on the Arsenal beach among the coal heaps and the bunches of bananas. My father, seated at the door of his house, received them by closing his book, an act of reverence he granted to strangers. They asked for the dancer. A program of the performances of her dance group had arrived in their hands.

-We have come to ask her to help us research Colombian musical folklore, they said.

My sister smiled. She was always electrified when someone tweaked that nerve in her heart.

-Start with me, I am the folklore!

[…] Half an hour after meeting her, before going out to research with her the songs of the Blacks from Palenque, he began to record her voice, her deep tones, her laughter, the explosion of her silence. He understood that he was in front of a specimen of folklore not modeled by strange indifferences. He himself would get her a scholarship to learn with Katherine Dunham the techniques of modern dance.] (Excerpt from Levántate Mulato.) Zapata Olivella, Manuel. 1990, 324-5.

- This is a popular saying used to make fun of people who are withholding information.

Works Cited

Primary Sources

Colombia, Dept. Bolívar, 1964. Collection number 65-291-F. Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University, Bloomington.

George List Papers. Indiana University Archives, Bloomington.

Delia Zapata Olivella Papers. Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives, Nashville.

Zapata Olivella, Delia. ca. 1967. Ballet o Danza Folclórica? Páginas de Cultura. No. 15, Revista del IPC de Cali.

Secondary Sources

Alban Achinte, Adolfo. 2015. Conferencia Central Pedagogías de la Re-existencia. Keynote at UNIMINUTO – Cali. 1:28:42. December, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gPa7QRkZdKE&t=2s&ab_channel=CEDUNIMINUTO.

The Combahee River Collective. 1979. A Black Feminist Statement. In Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, ed. Zillah R. Eisenstein. New York: Monthly Review Press, 362.

Escobar, Arturo. 2020. Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham: Duke University Press.

Haber, Alejandro. 2011. Nometodología Payanesa. Notas de Metodología Indisciplinada. Revista Chilena de Antropología, 23.1: 9-49.

List, George. 1983. Music and Poetry in a Colombian Village: A Tri-Cultural Heritage. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Quijano, Aníbal. 1992. Colonialidad y Modernidad/Racionalidad. Perú Indígena. 29:11-20.

Valderrama, Carlos. 2015. Black Politics of Folklore: Expanding the Sites and Forms of Politics in Colombia. Master’s Thesis. University of Massachusetts Amherst, https://doi.org/10.7275/5246752.

Zapata Olivella, Delia. 1967. An Introduction to the Folk Dances of Colombia. Ethnomusicology. 11.1:91-6.

Zapata Olivella, Manuel. 1990. Levántate Mulato!: Por Mi Raza Hablará el Espíritu. Colombia: Rei Andes.

URLs

Instituto Popular de Cultura: https://implentaciones-ivw.com/ipc/page

Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University https://libraries.indiana.edu/archives-traditional-music

Indiana University Archives https://libraries.indiana.edu/university-archives

Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives https://www.library.vanderbilt.edu/specialcollections