Photo by Riki Saltzman.

Introduction

by Emily West Hartlerode

A folklorist’s approach to interviewing is not only a technique employed for producing high- quality archives, valuable ethnographic research, and compelling public products, and it is more than a set of skills to teach and share with individuals and communities who want to produce their own records. It is also a communication style useful in networking and collaboration. In this article, co-authors Emily West Hartlerode (Oregon Folklife Network/OFN), Makaela Kroin (Washington State Parks and Recreation), Ken Parshall (Jefferson County School District), Anne Pryor (Wisconsin Teachers of Local Culture/WTLC), Riki Saltzman (OFN), Dana Creston Smith (Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs/CTWS), and Valerie Switzler (CTWS) contribute perspectives on our collaborative design, support, and delivery of folklife field schools at CTWS in 2016 and 2017. The partners engaged in a process that involved careful conversations among collaborators, conversations that drew upon interview skills like careful listening, asking clarifying questions, and checking back for accuracy.

Whether our cross-cultural collaborations bridge cultures like ethnicity, occupation, age, gender, or even sovereign nations as when Tribes engage state programs in nation-to-nation relationships, differing communication styles always pose challenges. Direct and indirect communicators ideally learn to respect and understand each other despite different, often culturally embedded, ways of articulating things like preference, task completion, and delegation. Add to these complexities the various forms of communication available to us (email, phone, face-to-face), and we are bound to misunderstand any number of details. Interviewing techniques can be a helpful tool for ensuring that collaborators’ ideas are heard and adhered to. Practitioners can also learn from communication successes and challenges in our partnerships, which enable them to become better interviewers by bringing these lessons back to our methodologies.

When our communications succeed, the resulting collaborations add exponential value to projects and extend the impact and reach far beyond any one project or single institution. We gain trust and build lasting relationships that seed new ideas and enable future partnerships. We learn more deeply about each other and develop empathy, which serves us in all our relationships; at the same time, the process sows seeds for new ventures. By pulling together the various perspectives and plural voices from the collaborative field school project for this article, the partners were once again challenged to articulate and unify different versions of a shared story. We hope to deepen our relationship even further through this process as we share our collective experiences as a model for other collaborations.

Further Background

by Riki Saltzman

Thanks to work that James Fox (now at California State University, Sacramento) and Nathan Georgitis (University of Oregon/UO Libraries), as well as Emily Hartlerode, had previously done in collaboration with CTWS for an audio digitization project, we learned of Valerie Switzler’s priority to have youth participate in her Culture and Heritage Language Department’s initiative to interview tribal elders. Switzler’s goal was to enhance the archives at CTWS and engage CTWS youth in their heritage and tradition. As we at OFN were thinking about a field school of some kind, we imagined with Valerie that if OFN staff offered to teach documentation skills to high school students, perhaps they could get UO undergraduate course credit for interviewing elders. At that time, OFN’s goals also included involving UO Folklore students as co-learners along with CTWS teachers to create a unique, immersive experience of learning, professional development, and fieldwork. As it turned out, we weren’t able to involve either teachers or UO Folklore students in that way. For the first year, we enlisted OFN’s most recent Summer Folklore Fellow, Makaela Kroin, who had just completed her MA in Public Folklore and had extensive teaching experience. The second year, we were able to include Folklore graduate students Jennie Flinspach and Brad McMullen, who earned internship credit for their excellent work. Both had teaching experience at UO, and Flinspach was particularly effective because of her first career as a public school teacher.

During the early planning process, we learned from Valerie that middle schoolers, not high schoolers, should be the field school target; they were the most at-risk and in need of such training. Valerie connected us with Ken Parshall, then a relatively new principal of the CTWS K-8 Academy. During our initial phone conversation with Ken, he enthusiastically embraced the field school idea. But it was our face-to-face conversations that were critical to establishing the strong collaborative relationship that allowed us all to succeed. Ken’s participation was critical to the success of this project. Teaching is his passion, and motivating students to learn and succeed is his life mission. During our first in-person meeting, as he told us stories about his work and his students, he teared up, as did we. This man inspired not only students but also teachers and parents. Ken’s goal was to increase literacy and get more students on the path to college. For example, to get students excited about attending college, he instituted “college day” at the Academy, which involved getting a college t-shirt for every child to wear, even the kindergarteners.

Ken’s goals guided the field school’s development. To introduce the opportunity to students, he suggested that he and his staff invite families to come to an orientation meeting on an evening when a school supper was already planned. Then OFN staff would pitch the idea and scope to parents and students. We prepared our materials, and that summer’s OFN Folklore Fellow, Makaela Kroin, and OFN’s part-time program coordinator, Emily Ridout, and I drove three and a half hours from Eugene, over Oregon’s Cascade Mountains to Warm Springs.

While our talk with Ken gave us confidence to pitch the field school to families, the actual encounter was extremely challenging. The room filled with parents and students. Ken introduced us, and I introduced OFN as the state’s folk and traditional arts program. I listed all OFN’s prior collaborative work in digitizing valuable tribal archives with Valerie’s staff. We drew connections between OFN’s documentation of their tribes’ master artists for our traditional arts apprenticeship program and the field school project, which was for students to document tribal elders and contribute that work to the CTWS archival collection. Despite what seemed an impressive foundation for ongoing partnership, neither students nor parents reacted much or provided feedback to my over-the-top introduction. The reticence was palpable and evidence that we had no actual relationship with these young people and their families. Parents had absolutely no reason to trust us with their children or this project. I was talking at them instead of having a conversation with them. Emily Ridout and Makaela spoke next about the details and passed out registration paperwork for parents and students to complete. That got a bit more chatter, and we answered questions one-on-one. Those beginning conversations were the actual start of our relationships with students; it was the field school experience itself, with Anne Pryor, Emily Ridout, and Makaela, that created an essential, in-depth rapport with the students.

2017 field school staff and students. Photo by Brad McMullen.

Summary of Project

by Ken Parshall

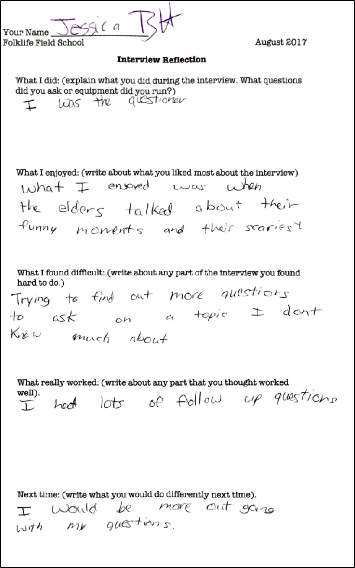

As the principal at Warm Springs K-8 Academy, I had the opportunity to partner with the OFN, University of Oregon, and Warm Springs Culture and Heritage Department to provide an amazing field school for some of our middle-school students. Over the course of two summers, two separate groups totaling 30 students, participated in a week-long learning project that allowed them to become familiar with research, culture and heritage, and archiving. This learning involved students eventually selecting their own project, conducting research, archiving that research, presenting their project to family and community members, and finally presenting their project to college staff during an overnight visit to the UO campus.

Students who completed all phases had the opportunity to earn one college credit at UO. This credit alone was powerful for the students and their families. Historically, our community has had a graduation rate far below the state average. I believe the confidence instilled in students that they are capable of doing good work and earning college credit will serve them well as they enter high school. Part of success in high school and college is simply believing that you are capable of success.

OFN staff traveled to Warm Springs and stayed in the area during the week of the field school. They met many community elders, staff from the Culture and Heritage Department and Warm Springs K-8 Academy, and family members of the students involved in the program. I found them wonderfully supportive and encouraging of our students. They had to push some students out of their comfort zones. However, they always pushed encouragingly and students developed trust and improved their effort and confidence over the course of the week. The field school was a wonderful learning opportunity for our students and a celebration of their learning, their families, and this amazing community.

2017 students practice interview skills.

Photo by Makaela Kroin.

Project Management

by Makaela Kroin

As a community-steered collaboration, the field school required a great deal of flexibility, a nimble approach to problem solving, and sensitivity. Unknown variables challenge the most seasoned program planners, and in both years the project staff responded to last-minute changes in resource availability, project theme, and final product. Extremely impactful to the entire community at Warm Springs was a wildfire in Year 2 that displaced several students and caused the evacuation of key project staff due to smoke inhalation.

Our team of folklorists and local tribal members exhibited the creativity and resilience needed to translate most of the surprises into learning experiences. Repeat project staff helped smooth the challenges. Anne Pryor’s expertise in Folklore in Education was essential, as was her patience. Invaluable support came from Dana Creston Smith, a tribal archivist whom Valerie provided from her staff to support the field school. Alongside his extensive relationships with families at CTWS, Dana had augmented his background in radio and audio technology with OFN’s archives training during the Sound Recording project. He deepened students’ engagement with OFN, thanks to his positive experiences with both. And my own participation as a Year 1 classroom aide and Year 2 OFN project coordinator provided important consistency and institutional knowledge.

Despite prior collaborations between OFN and CTWS, our fieldwork team arrived as outsiders to the youth in Warm Springs. Their adolescent silence, typical of their age, was exacerbated by the cultural divide and history of high teacher turnover. Building relationships with students was the initial goal, and critical to delivering any curriculum. Fortunately, Dana and two local teaching aides knew the students and provided indispensable insights. Their encouragement bridged the divide and softened barriers, and student resistance gave way to boundless energy by midweek.

In response to Valerie’s request to increase youth experience with technology, the Year 1 team included MA graduates from UO’s Folklore Program, which emphasizes transmedia fieldwork skills. Warm Springs students learned to use fieldwork equipment and produce digital products. That year, a family folklore theme gave us the greatest flexibility in working with many unknowns. The autonomy to conduct their interviews independently with a family member after class worked well for some students. However, some had equipment malfunctions, and others were unable to coordinate time with a family member. Producing PowerPoint presentations to share what they had learned from their interviews was outside many students’ reach, as well. Where these challenges became apparent, staff provided a great deal of one-on-one support and after-class time to keep student success an achievable goal.

Dana Creston Smith discusses the importance of and professions in archiving with 2016 students during a site visit to the Culture and Heritage Archives.

Photo by Anne Pryor.

Curriculum

by Anne Pryor

While planning the field school curriculum, we strove to balance multiple goals in the design and content of the field school. Some goals were original to our design and others we added after consultations with community partners.

- Folkloristic goals related to best practices in cultural documentation led to students interviewing each other, family members, and community members; recording interviews; processing interviews; and visiting several tribal archives.

- Cultural goals to document living practices and traditions in the community led to students interacting in multiple ways with knowledgeable cultural practitioners, identifying valued cultural elements observed in the community and heard in interviews, and analyzing interviews for cultural content.

- Educational goals to enhance literacy skills meant we spent time reading, writing, and discussing content. Students wrote daily reflections on their work and experiences in the field school. The most challenging exercise included interpreting the formal language of UNESCO conventions on maintaining cultural heritage.

- Experiential goals to have students as agents of their own learning in active, community-based, culturally relevant ways meant that, whenever possible, students made their own topic selections and chose whom to interview, and the group interacted in the community whenever possible, despite logistical challenges.

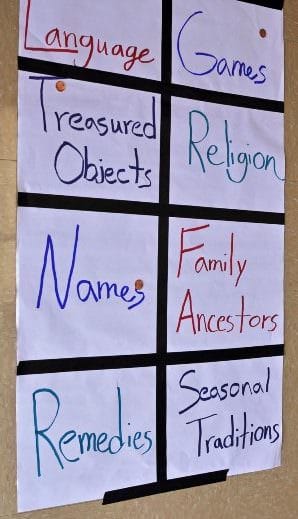

- Fun goals to have an enjoyable field school meant that we included team building games, lessons that were structured like games, and daily free time for playing in the gym or outside. One especially successful learning game was “Coin Toss,” in which each student and staff tossed a penny onto a grid and then told an example from their life to illustrate the cultural element in their grid square.

Coin toss game board using cultural elements was a fun way to introduce key concepts.

Photo by Anne Pryor.

Each day was sequential, building on the previous material and experiences. Basically, Day 1 introduced key concepts and individuals; Day 2’s focus was interviewing techniques; Day 3 was working with the recorded interviews; Day 4 required content analysis; and Day 5 was finalizing presentations. Fieldtrips to key cultural sites such as KWSO 91.9 FM tribal radio station and the archival collections of The Museum at Warm Springs and the Warm Springs Culture and Heritage Department accentuated the in-class material, connecting it with tribal cultural projects.

Specific ethnographic skills included how to read objects for cultural information, compose effective photographs, find cultural information in photographs, practice good interview etiquette, compose questions to elicit basic information and questions to elicit narratives, employ active listening, operate recording equipment, create audio logs, transcribe audio, compose introductions of interviewees, summarize a key cultural element from the interview, provide constructive feedback to their peers, speak clearly in a public presentation, and write thank-you notes.

We selected the topic of family folklore as the organizational focus for 2016 because, being unsure of access to community resources, we needed a reliably rich content source that could be easily accessed by the students. That indeed gave us great stories and information about topics such as traditional practices for gathering berries and roots, fishing for salmon on the Columbia River, occupations like wheat farming or boxing, favorite family food traditions, or life lessons like “help people first before you help yourself.” However, multiple community voices urged us to focus solely on interviewing elders to preserve their wisdom and experience. The following year we followed those requests more directly.

In 2016 for family folklore, students conducted one or more interviews with family members in the evening outside class, using a recording device of their own or borrowed from the field school (OFN made equipment available to the project). Students processed that interview and developed a short slideshow according to a predesigned outline. In 2017, recruited community elders came to the school for group interviews; we dispersed into four groups, each with three to four community elders, three to four students, and a folklorist, and each group had a camera, a video or audio recorder, or both. Afterward, students selected a segment of the interview, transcribed it, and wrote and recorded an introduction of the speaker explaining why the content was culturally significant. Students presented the final products of their fieldwork to members of the Warm Springs community before repeating the presentation in Eugene at UO. Honing public speaking skills thus became an additional goal.

Full, active support by each partner led to success. One result was having multiple staff in the classroom each day—OFN folklorists and graduate students, K-8 Academy aides, and Culture and Heritage Department personnel. Each brought invaluable assets. Without this intensive staffing, accomplishing the ambitious goals in five days would have been impossible.

Local Support

by Dana Creston Smith with Emily West Hartlerode

Recognizing his essential role, the authors asked Dana to contribute his voice to this article. However, competing obligations did not provide him that kind of time. In line with this project’s dedication to flexibility, and in the spirit of this volume’s “Art of the Interview” theme, the team decided that I should conduct a phone interview with him to gather his reflections and broadcast his perspective on the project.

DS: When we first started, you [OFN] had some equipment, and we [at Culture and Heritage Archives] had some archiving auditory equipment we used to show the kids how to preserve stuff…. We had a desktop recorder, pen recorders, disk recorder, cassette tape recorder, even dual cassettes, and some of the kids made iPhone recordings, born digital. They enjoyed learning the different techniques and equipment used to gather the materials. Some of them had iPhones and had [their interviews] done before they arrived at the Archives for the fieldtrip. Even those ones took notes, recorded, and used what they learned on their tour of Culture and Heritage.

[Students] wanted someone there who could tell them about their history. As they started their projects and doing recordings, I actually went to their house and helped them. Showed them how to set up questions for their interviews. Went to their house if they were too bashful to talk in class. One of the kids couldn’t finish because his family had to be evacuated for a few days [during the forest fires], and he got real sick.

Even stuff like grammar—some of what they learn in school is hard for them to retain. I asked them, “What did you learn in writing—how to make a sentence?” I told them, “Listen to your interview and pick out the parts you want,” as they put their audio collages together. They didn’t want to type the whole thing out. I told them, “This is your project, so pick out the best parts.” Their grandma talked about the solar eclipse and it wasn’t a good thing, so they went inside the house and then when it was over, they came out. And while they were inside, they sat at the table and sang songs. I showed them how to mark the audio (in/out times) to help with the editing.

Grandparents, uncles and aunts, family came out to the [student] presentation. I like how all the OFN staff did their presentations at the kids’ level. But them not knowing the students, Indian kids and culture… I helped them connect with students. I helped them translate. I can read and write in all three languages. So [I could help] if an interview included [Native languages like] Ichishkíin or a Wasco word. I encouraged kids to ask people who use their Native language [what they mean]. Even if it’s not in Native language, you can ask. You know, sometimes an interviewee uses bigger words that they don’t know. Second year—interviewing the language teachers. Then they broke apart after the interview and each of them got to work on their audio collage.

EH: In my interview with Dana, I discovered his far-reaching support as a classroom aide, cultural diplomat, community scholar, and dedicated friend to all involved. He described drawing upon all his resources, personal and professional, to ensure student and project success. I hear in his story that he essentially interviewed the students about what they liked about their interviews and helped them go back and listen for those sections. He got them talking about what they liked as a path to writing their introductions and later recording them for their audio collages. This kind of oral/verbal processing may be an important cognitive form of prewriting for many types of learners and would help those whose thoughts don’t immediately translate into typing and writing.

As noted earlier, the field school concluded with public presentations, one of which was to their home community. The other was part of an overnight visit to UO that included touring campus, eating in college dining halls, and sleeping in the newest dormitory. We coordinated on-campus visits with lots of consultation and engagement with UO’s “Native Strategies,” a working group of faculty and staff who unify their independent efforts to support Indigenous student/faculty/staff academic, professional, and programmatic advancement. Members contributed generously, resulting in meetings with UO’s Native recruitment and retention specialist, a viewing of Edward Curtis original photographs at the Special Collections and University Archives, sharing lunch with Native American Student Union members at UO’s Many Nations Longhouse, and playing a Native sport called sjima, or shinny ball, to let off some anxious steam about their presentations.

These value-added features proved critical to success and future fundraising because, combined with the college credit students earned, the field school became a pipeline project of value to university partners. I question whether Native Strategies members would have made their crucial investments without having first built relationships by attending monthly potluck meetings in order to learn about the issues affecting Native students/staff/faculty and share about OFN’s projects with tribes. I am grateful for lessons and best practices I’ve learned sitting in council with these Indigenous partners, a process akin to the interviewing practice of listening, sharing, and reflecting back what I’m hearing.

Leveling hierarchies is another folklore interviewing skill that supported a successful inaugural field school and allowed us to develop a second-year program. Although as interviewers we may have preconceived ideas born of outside knowledge and past experiences, we set them aside and listen to what is present for the interviewee. We ask questions to explore the unexpected. And we recognize ourselves as stewards of the story that emerges, the story of the folk, even (or especially) if it flies in the face of what the institutions report. I recall swallowing my pride in our presumed victories in Year 1 to revise and revamp based on a crucial piece of feedback from Valerie. By selecting family folklore as an accessible theme, the project neglected her key goal to interview specific elders. And so we made sure to partner with her more closely in Year 2. Another crucial piece of feedback came in watching students struggle with the PowerPoint technology and public speaking anxiety. Makaela and Anne, returning for Year 2, felt that learning waned for youth overburdened by these expectations. We planned on modifying the product and theme, and circumstances required them to revise the interview process, too.

Students visit the KWSO recording studio.

Photo by Anne Pryor.

Building on Our Achievements

by Makaela Kroin

In Year 2, students produced group audio projects with their individual audio projects nested within. After each student selected a portion of the group interview that they found interesting, they recorded introductions, analysis, and conclusions to include. These audio projects were designed to maximize student ability to communicate their reflections with others. We worked with students one-on-one to express their reflections, write them in short essay form, and audio record their scripts. Students who were ahead helped other classmates, contributed to the group project, or added photographs. Both the theme and the final project needed to be flexible and scalable to work with a variety of comprehension levels and logistical considerations.

Connecting students to specific elders on predetermined topics in Year 2 was more ambitious than predicted, and nearly failed. Miscommunications became apparent when staff at the senior center, where we thought interviewees expected us, did not anticipate our arrival and could not accommodate what for them was a last-minute drop-in by 20+ youth and staff. Anne and UO graduate student classroom aides Jennie Flinspach and Brad McMullen hastily rearranged the curriculum for the day while Dana and I walked down reservation roads, canvassed the elder center, and knocked on doors. Despite our efforts, we didn’t really know how many elders would arrive at the school for interviews the following day. Anne’s brilliant solution, group interviews, gave us the flexibility to accommodate whatever elders and students were in attendance, and the results were fantastic.

In both years we ended up reevaluating our plans and expectations to match reality during our on-site week in Warm Springs. After long days in the classroom, our team gathered for dinner to debrief and radically reformat the following day to integrate the latest developments. Our days had Plans A and B, some even had Plan C. If we couldn’t get a confirmation for a fieldtrip or the students became too antsy, we developed a cache of back-up activities bolstered with ideas from those of us with experience as camp counselors or youth drama instructors. These nightly gatherings were as much support groups as they were work sessions that again put interviewing skills into practice by listening deeply, asking clarifying questions, and reflecting back what we heard for accuracy.

Co-designing partnership programming is challenging, but it’s incredibly meaningful and instructive. Students produced final projects that contained cultural information and personal insights and demonstrated experience with cultural documentation processes. Students discovered that they had a wealth of traditions in their families ranging from rodeo and ranching traditions to fishing from family scaffolds, First Kill ceremonies, beadwork, tanning, and more. The results went beyond improving students’ traditional knowledge and pride. We heard feedback in Year 2 that a Year 1 student who exhibited some typical “class clown” behaviors had become markedly more focused and was earning higher grades. The relationships we cultivated with the students and one another made those very long days bearable at the time, exceptional in retrospect. These personal and institutional relationships continue to bear fruit in wonderful and surprising ways for many of us, a lovely reminder that the most valuable outcomes are often the most elusive to document.

Outcomes

by Dana Creston Smith* and Riki Saltzman

DS: Some [students] came back and talked [to me] about their grandma, great-grandma. [I told them] “You’re related to a lot of people—probably most of the reservation!” I still have some of the students call me, even just a few months ago. They were asking about applying for jobs and wanted me to give them a little information about what they did [in the field school]. They knew it. They just wanted reassurance.”

RS: Despite UO funding cuts that prevented collaborators from offering field schools beyond these two, Valerie asked OFN to involve former field school students in experiences at a once-in-a-lifetime event. The Confederated Tribes secured the loan of the original 1855 Treaty from the National Archives, and the resultant exhibit display at The Museum at Warm Springs became the centerpiece for a pan-tribal conference during the late fall of 2018. The treaty, which “defined the area of the Reservation and affirmed Tribes rights to harvest fish, game, and other foods on accustomed lands outside the reservation boundaries,” is the seminal living document for CTWS, and everyone there had strong emotions about it.

Valerie suggested elders to invite for interviews during the conference, and we had a few sign up in advance. Student participation was key to the success of this project, however. When we let attendees know that students would be among the interviewers, several more elders asked to be part of the process. Three from the 2016 field school—Dylan Heath, Taya Holiday, and Kathryce Danzuka—now high schoolers, took over the interviews. After a brief training on the video equipment and reminders about interviewing procedures, they showed considerable ease, attention, and maturity in their roles. Because the elders were so enthusiastic about the students’ participation, the resulting audio and video documentation was much more detailed and deeper than anything Emily West Hartlerode and I could have elicited on our own.

*Dana’s words come from an interview with Emily West Hartlerode.

Conclusion

by Riki Saltzman and Emily West Hartlerode

Both years of the folklife field schools at Warm Springs were a success because so many committed and devoted people were involved. We believe that a good part of that commitment was the result of extending the “art of the interview” beyond the content of the curriculum; our interviewing skills were a key element of our collaborative partnerships. Interviewing, like collaboration, is all about relationship building, and both benefit from using best practices like meeting in person, asking thoughtful questions, listening to those responses, and checking back to confirm details, permission, and next steps. When projects have hiccups, these interview skills form a strong foundation for getting things back on track; nurturing the relationship is central—any project is secondary. The authors intend to continue adopting and expanding this exercise by looking closely at the skills we teach and then applying them broadly in our professional practices in ways that keep us learning and growing. We encourage our readers to do the same.

For Further Reading

Anne Pryor compiled multiple resources that served as useful starting points for creating specific materials for the field school curriculum:

- Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. 2016, https://warmsprings-nsn.gov.

- Falk, Lisa. 1995. Cultural Reporter: Reporter’s Handbook. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History.

- Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program. 1992-2012. Louisiana Voices: An Educator’s Guide to Exploring Our Communities and Traditions, http://www.louisianavoices.org.

- Richman, Joe. 2000. Teen Reporter Handbook: How to Make Your Own Radio Diary. New York: Radio Diaries, Inc.

- Wagler, Mark, Ruth Olson, and Anne Pryor. 2004, Kids’ Guide to Local Culture. Madison, WI: Madison Children’s Museum.

Emily West Hartlerode is Associate Director of the Oregon Folklife Network, managing collaborative projects, administering grants, and supervising graduate students. She also supports folklife programming at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon. Her focus includes feminist ethnographic filmmaking and decolonizing methodologies.

Makaela Kroin is Folk and Traditional Arts Program Coordinator at Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission. She develops partnership programs to support and celebrate Washington folklife. She serves on the board of the Center for Washington Cultural Traditions.

Ken Parshall serves as Superintendent of the Jefferson County School District 509-J in Central Oregon. He recently completed his 33rd year as an educator in Oregon, where he has served as a high school math teacher for 12 years, a school administrator for 18 years, and as Superintendent the last two years. He has been the principal of three high schools, one middle school, and most recently served as the principal of the Warm Springs K8 Academy for three years.

Anne Pryor is a co-founder of Wisconsin Teachers of Local Culture, the board chair of Local Learning: The National Network for Folk Arts in Education, and the former state folklorist of Wisconsin. Her research and public outreach areas include folklore in education, Iroquois raised beadwork, Marian apparitions, and traditional cultures of the Upper Midwest. She is author of Listening to the Beads and co-author of the Kids’ Guide to Local Culture, among other publications.

Rachelle H. (Riki) Saltzman is Executive Director of the Oregon Folklife Network. That position involves collaborations with groups and organizations to develop projects, grant writing, and public presentations. She also teaches classes in Folklore and Foodways and Public Folklore at the University of Oregon. Her interests range from festival, food, and place, to ethnic identity and cultural heritage.

Creston (Dana) Smith was hired and trained to digitize heritage sound recordings on open reel under a 2013-14 National Parks Grant. He has strong technology and communication skills, including the ability to distinguish Ichishkiin, Numu and Kiksht—the three languages of Warm Springs (vital to determine translation contacts). He has successfully completed two projects for the department as a Culture and Heritage Language Department Media Specialist.

Valerie Switzler is General Manager of Education on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation of Oregon overseeing all branches—from early childhood to higher education—including culture and heritage, Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, vocational rehabilitation, and Oregon State University extension. She has served on numerous boards and committees that focus on heritage languages, cultural preservation, and revitalization of traditions and works vigorously to promote education that is relevant to Native American world-views. She has taught her heritage language nearly 20 years and continues to advocate for all heritage languages.

URLs

Audio Digitization Collaboration (CTWS and OFN):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6o_jQOZ2dNw

OFN blog post about conducting interviews at the Treaty of 1855 Conference at CTWS: