Standing on the threshold of the schoolhouse door surrounded by the flow of traffic moving between the community and the classroom, I notice a pile of what appear to be discards cast to the side outside the doorway. Much of the pile is community knowledge and community ways of knowing that will be retrieved later when the dismissal bell rings. Peering around the doorway, I see a similar pile of school knowledge and school ways of knowing that are left inside awaiting the next morning’s welcoming bells. This taking off and putting on of culturally situated knowledge is a regular feature of all our lives as we move between the many cultural groups and contexts that make up our daily existence. We know, for example, that we cannot bring those jokes and ways of joking that we do with our friends into our family dining room, religious school, or workplace, so we leave them outside. Certainly, school-inappropriate jokes are in that pile outside the schoolhouse, but so too are most of the community traditions and experiences that make up the bulk of students’ lives in non-school hours. For immigrant, refugee, and minority students in particular, I wonder whether these youngsters feel that they could keep anything with them as they entered the school building.

I invite readers to look more closely at what students passing through a school portal may get to take with them and consider why being able to bring in more benefits youngsters. To help educational practitioners think about ways to do this, I examine several instructional practices frequently employed in folklife and folk arts education that productively strive to increase community knowledge and ways of knowing as resources for student learning.

Knowledge and Ways of Knowing

As I discuss knowledge, I am referring to the subject matter, the what, that is known and gets to count as knowledge. Knowledge has content, the “stuff” known or being taught, as the focus. School knowledge can be classically understood as the canon of formal knowledge often encoded in standards or other means that declare what all students should know and be able to do at different points in their school careers. Community knowledge can be understood as content that is situated within a community cultural group or setting. Community knowledge can include the songs sung at celebrations or when jumping rope, the symbolic meanings behind ritual practices like decorating a Christmas tree, the organizational structure for storing food and dishware in the kitchen, the home remedies used to provide relief from common ailments, the expected exchanges when greeting someone, and the many other things that we each know for functioning well in our many groups every day. Bowman and Hamer (2011) have found that formal educators may refer to community knowledge as intrinsic knowledge whereas folklorists will call it traditional knowledge.

I define ways of knowing as: how one knows/learns/teaches/approaches the knowing/using of knowledge within its situated context. A classic school way of knowing for example would be didactic instruction in which the teacher presents an extended explanation of the material that the students are to learn and uses questions to direct student attention to information the teacher has already explained (Rose, et. al, 2001). Community ways of knowing are as varied as the cultural groups that use and pass on their knowledge. Transmission of community knowledge is often integrally linked to the continuation of traditions and makes allowances for variations and creativity to adapt to the specifics of a situation. A heavy reliance on observation with trial and error is a way that many games are transmitted in neighborhood streets, for example. Another way is when Grandpa guides young hands in how to handle tools while telling about a time when all did not go as planned. This way combines hands-‐on experiences with a historical dimension to pass on particular skills coupled with a sense of the contexts when they should or could be applied. Most often we are not fully aware of the many ways of how we came to know community knowledge, but these ways equip us all with a repertoire of learning methods that can be as situated as the content of the knowledge they teach.

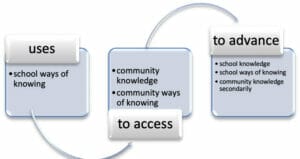

Community groups and contexts use community ways of knowing to transmit community knowledge and, classically, schools use school ways of knowing to advance school knowledge. Multiple researchers have pointed out how school knowledge and school ways of knowing are not easily accessible to all students. See for example the research by Heath (1983), Ladson-‐Billings (2007), or, better yet, review a discussion of the research on “the home-‐school disconnect” in Bowman and Hamer (2011, pp. 11-‐12). Lack of success is predictable when students struggle to gain access to school knowledge because of their not being proficient in school ways of knowing.

Schools tend not to give lots of validity to personal experience, as standardized tests so clearly show through emphasis on students demonstrating proficiency in a bounded amount of selected knowledge queried through multiple-‐choice questions. What is deemed a “good student” is further characterized by the youngster’s involvement in providing answers to, and asking questions of, the school canonical lessons. In school ways of knowing there are acceptable questioning topics that dis-‐en-‐voices other ways of questioning and discourse (Heath, 1983). All too often, the expected ways of participating in school do not leave room for a different profile of participation. Those students who are not expert at school ways of knowing and school knowledge have little room to voice at what they are expert.

Schools have desires to increase connections with many different cultural communities and the participation of their culturally diverse student population. Ladson-‐Billings (1994) found that successful teachers of one struggling group of students bridged the gap between school and home cultures by attending to the students’ cultures as a regular feature of their instructional practice. In culturally relevant pedagogy, teachers access community knowledge within students to advance school knowledge. Increasing the relevance of school knowledge, and making learning personally meaningful, are strategies to achieve greater student engagement. When students participate, they demonstrate competency and can give the teacher a different perspective on who they are and what they are capable of doing. Students who engage more can become more competent in school ways of knowing and develop a different perspective on school knowledge and themselves in relationship to it. Increasing student participation in school by tapping into their community knowledge in respectful ways that simultaneously support the youngsters’ cultural competency can positively affect academic achievement (Ladson-‐Billings, 2007).

Teachers wish to be expert in what they are teaching, but no one can possibly know all the community knowledge and ways of knowing in any given community. Allowing community knowledge and ways of knowing into the classroom requires teachers to be learners and reflective about their own practice. It is not surprising that teachers might devalue community ways of knowing without knowing they are. Certainly this could happen when educators pay insufficient attention to the dynamics of the politics of cultural differences that solidify these differences into borders with unequal power exercised across it (Erickson, 2007).

Methods for Accessing Community Knowledge

By presenting several examples of folklife education activities that use school ways of knowing to access community knowledge and advance school and community knowledge, I seek to increase teachers’ comfort with expanding their instructional repertoire to include more folklife education practices. The following activities are easily accessible to all teachers, generally do not require funding, and can be managed within a single classroom. With each example I explore the intersections between the school and community ways of knowing and bodies of knowledge. These intersections show the complex relationships that can and do occur within each method of including more of the community in instruction. The diagrams consistently show that these activities all start with teachers’ expertise in using school ways of knowing. Educators who seek to advance the success of all students, particularly immigrant, refugee, and minority students, will find suggestions of activities that others are finding useful. I draw my examples from the Folk Arts–Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) in Philadelphia, a school dedicated to including folk arts as an integral part of student learning. This is not an exhaustive list of folklife education practices. There are many other methods within folklife and folk arts education models across the country that could provide further inspiration.

Lion dancers at Philadelphia’s Chinatown community Mid- Autumn Festival. Photo by Eric Joselyn.

Cultural Texts

One way to access community knowledge is through the inclusion of texts from students’ cultures. This instructional activity is one common in multicultural education programs. It promotes the use of instructional materials that go beyond the classic canon of texts to include literature, music, and art from multiple cultural groups. As students read, sing, and make art projects from a cultural group, they learn about the knowledge of that cultural community. If the cultural group whose texts have been selected for inclusion is a group a student identifies with, then s/he can “see” her/himself included in the classroom (Banks and Banks, 2004; Grant and Sleeter, 1998). Although these texts may contain some glimpses into community ways of knowing, most teachers primarily use school ways of knowing to access the texts and advance school knowledge within mandated curricular objectives. Character and plot can be taught by using an Asian folktale, rhythm and harmony by using a South American folk song, and shape and design elements by using an African mask. However, care must be taken to avoid common pitfalls like assuming that all the Asian students, regardless of where in Asia their families’ roots might be, will know and relate to that folktale, or teaching a token folk song without its community cultural context.

Figure 1: Cultural Texts

When folklife educators use cultural texts for instruction, they take care to minimize the use of overgeneralizing materials that reduce a cultural group to a few essential traits and seek out materials that emphasize variability and change as normal cultural features of a group. They will select texts carefully to maximize the connections with students. For example, FACTS has some Liberian students and uses a printed collection of Liberian folktales gathered in a Philadelphia senior citizen center as a language arts textbook for learning about developing characters in stories. Local communities contain readily accessible texts that can be more applicable to students lived experiences by virtue of these being things they have seen or heard before. If it is a story the student has heard, s/he could add to the lesson and demonstrate expertise by sharing contextual information about its local use. Community centers, archives, galleries, museums, ethnic clubs, and religious centers are places that may have printed versions of locally told stories, recordings of local musicians, and pieces of art that could be photographed or loaned to teachers. The Internet is another rich resource for instructional materials as organizations and individuals in every community capture and post their traditions in multiple media formats.

Texts are broadly defined by Botel and Lytle (1988) to include written and oral texts, multimedia artifacts, and children’s experiences and can be authored by anyone, including the children themselves.

Students’ Experiences

One of the most easily accessible resources of community knowledge is the everyday experience and cultural practices of students themselves. When students are asked to recall, reflect upon, and share their life experiences as a part of instruction, these memories and stories become available to be used as texts. Teachers use school ways of knowing when asking for personal experience recounting situated inside the classroom. It is hard to know the many varied ways that different community cultural groups do this, but even if a teacher did, these situated community ways, like telling family stories around the holiday table, would be difficult to replicate. As texts for instruction, students’ experience narratives can help advance students’ acquisition of school knowledge by enabling them to make connections to it that are personally relevant and meaningful. Interacting in reflective ways with their community knowledge also can provide students with opportunities to advance a deeper understanding about their cultural practices. Even though several students in a classroom might appear demographically similar, their families have had different life experiences that result in the unique variations that each student comes to know as their culture. Discussions using school ways of knowing about the many varied experiences of their classmates can further advance student understandings of community knowledge that may be similar or drastically different from their own.

Figure 2: Students’ Experiences

Annie Huynh, 4th-grade teacher at FACTS, describes how she used the school ways of knowing in her writing workshop unit to access students’ community knowledge about the bean cakes eaten as part of the Mid-Autumn Festival. She found that this helped more of her students advance in both their school knowledge about writing and their community knowledge of this tradition within so many Asian families (see article this issue).

Deeper understandings of other classmates’ cultures could be a secondary benefit in learning activities that use community knowledge as texts, as this FACTS teacher also found. But teachers could choose to advance students’ understanding of community knowledge as a primary goal by enacting additional or different curricular goals and instructional activities. When teachers use folklife education activities to direct students’ attention to noticing similarities and differences and patterning within these, teachers can be more deliberative in advancing student understandings of the complexities of culture and its processes at work in their lives. Erickson (2007) further points out that teachers, directly including students’ outside-the-classroom experiences in instruction, benefit more than the students. Teachers who do this advance their own development of non-stereotypical understandings of their specific students each year and thereby become more culturally sensitive practitioners.

[I]n every classroom there is a resource for the study of within-group cultural diversity as well as between-group diversity. That resource is the everyday experience and cultural practices of the students and teachers themselves (Erickson, 2007, p. 48).

Community Presenters in the Classroom

Students’ family members are another ready resource for including more community knowledge into the classroom. Increasing family involvement in supporting their child is desired by schools and families alike. Frequently family involvement in school is limited to the school communicating with the parent about their child’s progress with school knowledge and participation in school ways of knowing. Teachers open up the possibility for a different relationship with community members when they invite family or other community members into the classroom to share their community knowledge through activities like telling stories of their experiences, being interviewed by the students, or showing and telling about their traditions and cultural practices. These ways of sharing all use school ways of knowing to access the community knowledge that their visitors share with them.

By bringing community members into the classroom, the community knowledge they share is out of its situated community context. Even if the visitor is demonstrating how she quilts or pinches dumplings, the demonstration is one that is about the tradition rather than actually being the tradition. By this I mean, the context is so different for the visitor that she or he is making many decisions about what is appropriate to share in a school and what is better reserved for the doing of the tradition in the community context. Although it is not a fully enacted community practice, it is still possible for this instructional activity to access both community knowledge and community ways of knowing.

What the visitor shares becomes a text for primarily advancing school knowledge as the teacher makes use of this text to advance instructional goals. Advancing students’ community knowledge is a secondary benefit that occurs when students are exposed to the diversity of cultural knowledge and practices in the community. Teachers can make advancing community knowledge a primary benefit by making this an intentional instructional goal and including learning activities in the lesson that deepen the students’ engagement with the visitor’s and their own cultural knowledge.

Figure 3: Community Presenters in the Classroom

Teacher Huynh at FACTS discusses some parent visitors she invited into her 4th-grade writing class to share their stories and celebration traditions (see article in this issue). She noted how much more engaged all the students became in the lesson, but most especially the child whose parent was presenting. Although she used the community knowledge to advance the writing workshop curriculum, she describes an unexpected secondary benefit of expanding her own thinking about how oral narrative is an important way of knowing in her students’ lives. There are many resources on how folklife and folk arts education programs across the nation structure activities using visitors to the classroom to advance student understanding of community knowledge. Many of the instructional materials accessible on the Local Learning website, and through links found there, have been developed by folklorists who work in education and educators with experience in folklife. These instructional guides and tools pay attention to structuring learning activities that explore culture respectfully and help youngsters understand culture in more complex ways.

Community Field Investigations

The community outside the schoolhouse door is a very rich educational resource. Taking students out into the community to investigate community events, observe traditions, and interview community members as part of curricular units of study uses school ways of knowing to gather information and make sense of it. This folklife education instructional activity accesses community knowledge in its own context. Although community members will certainly shape their answers to student questions in response to their audience, what students hear, see, and experience will still remain situated in particular community ways of knowing and making sense of the world. Community investigations advance school knowledge through fulfilling the planned role for this activity within the curricular unit and advance school ways of knowing through developing the skills of data collection and analysis. As with the using of students’ own and visitors’ experiences in the classroom, advancing community knowledge is a secondary benefit resulting from exposure to different cultural perspectives and practices. Advancing community knowledge could be shifted into a primary goal through the inclusion of meaningful hands-on experiencing of the community practices and greater use of reflection to deepen students understanding of their own and others traditions.

Figure 4: Community Field Investigations

At FACTS, community investigations are built into the social studies curriculum and involve walking tours of a couple of Philadelphia neighborhoods. In 4th grade, the students go into the Chinatown neighborhood where the school is located, visit local businesses, watch a kung fu lion dance demonstration in an academy, and interview a master artist. There are many well-designed community investigations model programs in folklife education occurring across the country. Some programs with resource materials that could be adapted to other schools can be found through the Local Learning website such as these projects in Wisconsin (http://csumc.wisc.edu/cmct/HmongTour/index.htm, http://csumc.wisc.edu/cmct/ParkStreetCT/index.htm).

Other community investigation models incorporate components like identifying issues of importance to the community, developing student-directed projects, and service-learning experiences. In all community field investigations, it is worth pausing to consider the interrelationships between school and community knowledge and ways of knowing, particularly in how the learning activity values each. It is counterproductive for communities to experience school ways of knowing as disrespectful or as reinforcing political power imbalances in society. Community field investigations can be valuable for building stronger connections between schools and communities with many positive benefits for all involved, particularly for the students who experience and learn from their community in new ways.

Conclusions

As an institution, schools too often find themselves reinforcing societal imbalances, to the detriment of the young learners they are trying to support and advance toward success. Students quickly learn what aspects of themselves they can and cannot bring with them into the classroom, thus they leave far too many of their resources for learning outside the schoolhouse door. When students are invited to bring their personal experiences from the community into the school, this can counterbalance societal power-related cultural dynamics and validate the worth of that community knowledge. Helping students see their outside-of-school knowledge as valuable and the differences between their and their classmates’ community knowledge as variations that are merely different rather than less than or inferior in some way, opens up new spaces for learning.

Students have much to gain when they can bring more of themselves to school. Learning comfortably through school ways of knowing is not a challenge for some students, but for others it can be extremely challenging. Teachers cannot be expected to be cognizant of and proficient in the many community ways of knowing familiar to the students in their classrooms. Thus hoping a teacher could use multiple community ways of knowing to differentiate instruction, and facilitate each student learner with their particular familiar ways, is an expectation beyond what is possible in most classrooms. However, accessing community knowledge and incorporating it in instruction is realistic and possible in most classrooms. Community knowledge can serve as the bridge that enables a student to engage with school ways of knowing, advance in school knowledge, and become more successful in school.

Folklife education activities that use school ways of knowing to access community knowledge can increase student engagement and allow students to connect with school in deeper ways. These activities greatly multiply the resources that teachers can have available for instruction and open new possibilities for expanded discourse. Students generating their own texts of community experiences are creating new knowledge. Though folklife education activities in schools, students have a means and a context for sharing these aspects of themselves with others and for learning about how their experiences are shared or differentiated from their classmates’experiences. By opening up additional spaces for students to insert themselves into their learning, folklife education shifts the dynamics of teaching and learning, allowing students and community members to be featured as knowledgeable experts for all in the classroom to learn from, including the teacher.

By making particular student culture and family history a deliberate object of study by all the students in the classroom, the teacher can learn much about what he or she needs to know in order to teach the particular students in ways that are sensitive and powerfully engaging, intellectually and emotionally (Erickson, 2007, p. 50).

Gaining and deepening understandings of their students’ cultures is not an insignificant secondary benefit that teachers often experience when they lead folklife education activities. As teachers observe their students sharing, they gain new insights into their students’ lives and into how they can develop their own practice as culturally responsive and inclusive educators. The interrelationships between the school and community way of knowing and bodies of knowledges within folklife education instructional activities can enrich learning for all students. Tapping into this complexity opens up new dimensions inside the classroom, dynamic spaces that can accommodate students bringing in more of their cultural selves.

Linda Deafenbaugh coordinates folk arts education programs and research at the Philadelphia Folklore Project. She helped develop the Standards for Folklife Education by Diane Sidener and pilot them in K-‐12 schools and classrooms. Her research includes developing analytic methods for research teams looking at classroom discourse and social-‐cultural classroom dynamics (MUSE curriculum classrooms), teacher training in science education (funded by NSF), and urban youth definitions of community and cultural stressors that influence their mental health (Center on Race and Social

Problems/funded by NIH).

URLS

www.factschool.org

http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/wphila/stories/agape_wafrica_stories.pdf

http://locallearningnetwork.org

http://csumc.wisc.edu/cmct/HmongTour/index.htm

http://csumc.wisc.edu/cmct/ParkStreetCT/index.htm

References

Banks, James A. and Cherry A. McGeeBanks (2004). Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Botel, Morton and Susan Lytle (1988). PCRP II: Reading, Writing, and Oral Communication Across the Curriculum. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Department of Education.

Bowman, Paddy and Lynne Hamer (2011). Through the Schoolhouse Door: Folklore, Community, Curriculum. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Erickson, Frederick. (2007). Culture in Society and in Educational Practices. In James A. Banks and Cherry A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives (Sixth ed., pp. 33 – 61). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Grant, Carl A. and Christine E. Sleeter (1998). Turning on Learning: Five Approaches for Multicultural Yeaching Plans for Race, Class, Gender, and Disability (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Heath, Shirley Bryce (1983). Ways with Words: Language, Life, and Work in Communities and Classrooms. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria (1994). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria (2007). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory and Practice. In James A. Banks and Cherry A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives (Sixth ed., pp. 33 – 61). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Rose, C. P., Moore, J. D., VanLehn, K., and Allbritton, D. (2001). A Comparative Evaluation of Socratic Versus Didactic Tutoring. In Johanna. D. Moore Keith Stenning (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 897-902). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.