I work at the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) in Philadelphia. New teachers coming to teach at our school are unlikely to have had any courses in folklife education in their preservice training, so we kick off new staff orientation with a day that digs into the mission of the school, defines folk arts and cultural treasures, and provides a brief orientation to folklife education. One day working with terms, concepts, and methods gives them a taste and the flavor of the school and why folklife education is such a critically important and powerful approach to teaching and learning in a multicultural society. Teachers also appreciate gaining language to explain to others what their new school is all about when they are inevitably asked “What is FACTS—folk arts and cultural treasures?”

I work at the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) in Philadelphia. New teachers coming to teach at our school are unlikely to have had any courses in folklife education in their preservice training, so we kick off new staff orientation with a day that digs into the mission of the school, defines folk arts and cultural treasures, and provides a brief orientation to folklife education. One day working with terms, concepts, and methods gives them a taste and the flavor of the school and why folklife education is such a critically important and powerful approach to teaching and learning in a multicultural society. Teachers also appreciate gaining language to explain to others what their new school is all about when they are inevitably asked “What is FACTS—folk arts and cultural treasures?”

At FACTS, we are dedicated to developing advanced practices in folklife education, and as a charter school, we take seriously our role to share what we are learning with other educators. As we share at conferences and workshops, teachers and educational administrators and community tradition bearers alike give feedback about how important it is for them to have language to explain folklife education in ways educators can easily grasp. Such explanations help them to explain and justify the importance of teaching their students about culture and convince those they are working with of the value of using this educational approach. This article captures some of the language we use at FACTS for teacher professional development to communicate why the skills of ethnography and folklife education matter for student learning.

Folk Arts: Leveling the Definition

Kindergarten: Folk arts are what we do in our cultural communities.

Middle School: Folk arts are how a culture expresses itself.

Elevator definition for adults: Folk arts live at the intersection of art and culture. Every culture creates unique practices, call them arts if you will, and these practices make the most sense and have the most meaning when situated within the culture that creates them.

What are folk arts and cultural treasures?

Culture is layered and complex. See the Classroom Connections Activity Sheet to begin to create learning around how one might define “culture.” Before I start to define folk arts, I acknowledge that I also use the words “folk arts,” “folklife,” and “folklore” interchangeably. These three terms have a lot of overlap, but it’s not a complete overlap. “Folk” most simply means ordinary people—in other words, all of us. “Art” is simply defined as creative expression, “life” as ordinary daily living, and “lore” as words. The overlap is knowledge—the shared knowledge of a cultural group of people that underlies their creative expression, ordinary daily life, and words. But because “folk arts” is in the name of my school, I will consistently use the term folk arts in this section.

To teach within this intersection of art and culture, it is important to bring in community members to the classroom to teach about their folk art practice and to help students explore how the students’ own culture(s) may do something similar—or something very different. For example, Veronica Ponce de Leon comes to FACTS to teach about her cultural remembrance traditions (Mexican Day of the Dead). She guides students to explore their remembrance traditions while they create sculptures within her visual arts tradition. Students may have experienced skeletons as scary Halloween artifacts, but in Veronica’s tradition, skeletons are comforting. Used to remember those who have passed, they hold three layers of meaning that she shares with the students. In a folk arts residency with Veronica, students investigate how they remember their dead. It may be similar to parts of Veronica’s tradition (celebratory visits to graves), or not (with examples that include different practices using photo albums, chairs left empty, or talking through the wind or incense smoke).

One comparison for the topic of death and remembrance can be made in our school using the vertical curriculum model developed by Teacher Biaohua Lei on the history and traditions of the Tomb Sweeping Festival —清明节 Qing Ming Jie. Students engage instructional topics on traditions about death, as well as remembrance, and the worldview values they reinforce. Learn more in the 2022 Journal of Folklore and Education.

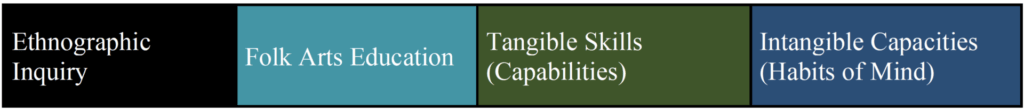

Figure 1. Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School Folk Arts Education Pie. © Linda Deafenbaugh 2021 (reprinted with permission).

Folklife Education: Major Components

Folklife education engages three core areas:

- Community knowledge and resources,

- A toolkit that includes skills developed in support of ethnography, and

- Cultural concepts and vocabulary that support nuanced and differentiated student analysis. (Figure 1)

The community knowledge component of the folklife education pie reflects the importance of using primary sources as resources for study. Some community knowledge resources may be in print form, but most are not. Community knowledge resides in the heads of community members. Perhaps this knowledge has never been recorded or written until students begin to re-present what they are learning from their study with community knowledge holders. (See Appendix for additional discussion of each of these major components of folklife education and its connections to formal education.)

In folklife education, students access the knowledge within the experiences of their families and communities through this specialized toolkit. Students become creators of knowledge resources, or primary sources, while becoming themselves active community members through experiential learning methods. Every community member holds golden nuggets of knowledge providing unending resources for investigation. The best thing is that this gold resides in every community, so through folklife education, rich resources for learning are easily accessible to every learner regardless of locale, economic, and other considerations and common limitations (Deafenbaugh 2015).

The folklife education approach is constructivist, as students create new knowledge through inquiry and discovery learning methods to explore the socio-cultural world we live in. We respectfully use authentic cultural resources when we tap into the community knowledge holders. Teachers guide students into exploring their own experiences and then connecting and comparing these experiences with those of others to arrive at new understandings of how culture works in a teaching technique called Me-to-We. (See the Classroom Connections for an extended activity on Me-to-We). By attending to ordinary daily life, teachers can direct students to slow down and focus more deeply on small moments encoded with cultural information—again presenting endless opportunities for learning about cultural processes. Frequently inviting students to pause and reflect on what they are learning in their study of culture helps solidify and expand student thinking in useful ways. Synthesizing activities furthers students’ skills as knowledge builders. Teaching students the skills of ethnography actively engages them in learning from and with their communities about culture.

Primary Texts and Diverse Cultural Communities

Getting students into activities or texts that have them interacting with others from different cultural communities is exciting for both teacher and students. I just caution teachers not to move too quickly to interactions with others, for doing so shortchanges the exploration of themselves that students need to do beforehand through activities like Me-to-We. This process builds the bridges that lead to inquiry rather than immediately to categorization. Without preparation for the encounter, students risk learning new stereotypes. “It is depressingly difficult to change stereotypes once they have been acquired. The evidence strongly suggests that it is easier to strengthen negative stereotypes than to weaken them” (Stephan and Stephan 2001, 38). So, avoiding teaching and reinforcing stereotypes is essential (Deafenbaugh 2017).

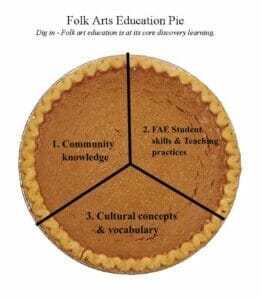

Figure 2. Ethnographic inquiry’s iterative cycle.

Teaching Students the Skills of Ethnography

Why emphasize teaching students the skills of ethnography? When we look at other fields like science or art education, those content areas seek to teach students the habits of mind of scientists or of artists. Likewise, folklife education helps students develop the habits of mind of folklorists and closely related fields that study culture (like anthropology and oral history). Developing students’ ethnographic skills is the central cornerstone for exploring culture—both one’s own and other cultures students may encounter throughout their lifespan. The method of approaching a new-to-them or a different-to-them culture with a question rather than an assumption will go far to fostering positive social interaction across differences in society. Developing the capacity for tolerating and respecting difference is teachable (Deafenbaugh 2017).

The iterative process of ethnographic inquiry (Figure 2) illustrates how students begin with question(s), go through a process of steps to investigate the question(s), and then go back to more questions to pursue by engaging in the ethnographic inquiry cycle again. Science educators may recognize overlaps between ethnographic inquiry and scientific methods. These similarities can open the door for folklife education and science education to be allies. But there are limitations. Ethnography has overlap with science’s study of the natural biological world, but it diverges from laboratory scientific methods. Culture is a uniquely dynamic phenomenon to study and folklife education equips students with ethnographic skills to investigate the social cultural world.

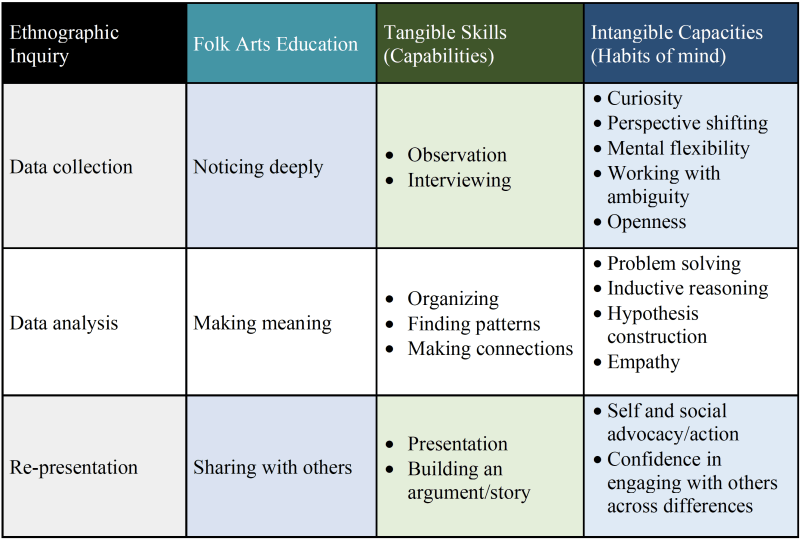

I developed a grid to help make visible some of what students are learning when we teach them to work with data in ethnographic inquiry (Figure 3). Although the question(s) students start and end with are not presented, questioning is an integrally important part of ethnography.

Figure 3. What we are teaching when we teach students the skills of ethnography through folklife education.

The first column lists common vocabulary for describing what ethnographers do as they move through the ethnographic inquiry process. These terms are recognized and used in and by the field of those who study culture professionally.

The second column provides terms that are more friendly-to-young-students for describing each step of ethnographic inquiry. FACTS is a K-8 school, so teachers appreciate having simpler language to use with their students when explaining and discussing the activities they are learning to do in their folklife education learning experiences.

The third column lists some of the tangible skills that teachers are teaching to develop student capabilities in each step of the ethnographic process. These are skills that can be concretely and directly taught. Students can be measurably seen to develop and become more capable in these skills through doing these steps of the ethnographic inquiry process repeatedly in a variety of folklife education learning experiences. Students develop listening skills as they learn to conduct interviews and record responses from their interviewees. To notice deeply, students develop skills in observing and record their observations from data they may gather through any of their senses.

FACTS 4th-grade students in Chinese Shadow Mask Puppet Theater residency. Photo by Messiah King.

To illustrate these skills, I will share an example from a FACTS 4th-grade student’s reflections after studying Chinese Shadow Mask Puppet Theater with master artist Hua Hua Zhang. In this classroom experience, the artist guided students to make and wear animal masks to act out a folk tale behind a shadow screen. The student wrote, “Before I thought shadow puppet was when people put their hand inside a puppet. But now I think it people who do shadow puppet.” 1 When students learn by doing, as they do in folklife education, they become participant observers and record deeper insights into a cultural tradition.

When students develop analytical skills in making meaning of the data they are gathering, they learn to find patterns, look for similarities and differences, and make connections. By relying on the data gathered, students seek explanations that the data supports. The 4th-grade shadow puppetry student described how she overcame her fear of performing with the mask as she recorded, “it made me feel brave…You couldn’t really tell who was on stage because it was shadow puppet!” The student continued her analysis with a further connection that showed the meaning she was making about the importance of this learning experience for herself and other students, “In school, you have to be brave enough that you will raised your hand.”

Re-presenting or sharing their data and the meanings they made through analysis is an important step. Students can develop their skills for sharing what they are learning through writing assignments, presentations, and synthesizing final projects. The 4th grader we are following wrote her findings in a one-page document that she placed in a decorated folder with some of her observation notes. She shared the new knowledge she had created with her classmates and her folder was hung in the school hallway for more students to see and learn from her insights.

The fourth column is not as easy to measure as the tangible third column is. It contains some of the capacities and habits of mind that students develop as they become more capable in the skills of ethnographic inquiry through folklife education. It is difficult to directly teach mental flexibility, empathy, or other habitual ways of thinking that are useful for positive functioning in a multicultural society. But students do develop these capacities as they become more capable with the skills of ethnography.

Reflection is an important practice at FACTS. Reflective thinking is used during data collection when students recall their prior experiences. Remembering and working with their memories to notice the details of their experiences more deeply helps them develop their observation skills while building mental flexibility. In thinking about that previous experience, the student is in a different place and time and can zoom into their memory to explore details and zoom out to examine the entirety of the experience. Students are developing the fundamentals of multiple perspective shifting as they look at their memories from different perspective points and the fundamentals of mental flexibility as they engage in shifting between these perspective points.

Reflection is also used in meaning making. Teacher-prepared reflective writing prompts guide students into exploring the data they have gathered about their own and others’ experiences to find the connections, similarities, variations, and differences. As students discover underlying common bonds between what they may have previously thought was complete difference, they develop a pathway for seeing others with more empathy. Whether students truly have become more empathetic to others is hard to measure tangibly, but they do develop a way of thinking that allows them to see others in a different light—and to see their underlying connectedness to others through surface differences. This mindset equips them with a pathway to developing empathy.

Conclusion

This article has focused on terminology and some of the underpinnings of what is taught in folklife education. I hope I have been able to convey that folklife education is much more than just content, and more than simply teaching artists coming in to work their magic with students. There are teaching methods that are useful for teaching the content that involve meaningful sustained interactions with knowledge bearers. There are learning experiences within cultural ways of knowing. There is learning with and from tradition bearers. And there is exploring one’s own cultural experiences. Folklife education orients education to a particular worldview.

We are all familiar with the dominant paradigm operating within education, which aligns the field of education with the field of psychology. This pervasive worldview focuses on the primacy of teaching and learning as taking place within individual brains. Thus testing, and more specifically standardized testing, has become a major tool to see what the individual student knows. Folklife education, however, aligns with the fields of anthropology and folklore. This worldview focuses on the primacy of the cultural context of learning. In folklife education, it is not just the study of culture, but it is also the attending to the culture of the classroom and the school. It is attending to the whole child in a learning environment. As the FACTS Teaching Artist Ngô Thanh Nhàn explains, students can only creatively express themselves as individuals when they are full members of the ensemble. It is in being part of the group that they learn to be an individual.

Because culture is so complex, and the contemporary world is so mobile, it is a certainty that our students will be interacting with culturally different people throughout their lives. If not sooner, then later. If not in the community, then in the workplace. Folklife education takes the knowledge, skills, and methods of those in the professions that study culture and makes them available to children and youth. Students already grapple with cross-cultural interactions, with misunderstandings, bias, and racism. They need help doing this. Folklife education is a welcome educational approach that empowers students to interact in their culturally complex lives with the confidence to figure out how culture works and how to have positive intercultural interactions. I look forward to hearing some of the definitions for conceptual terms that you readers develop to use with your students and some of the insights your students gain as you engage them in folklife education learning activities and the primary sources that can be found in your communities.

Find the Appendix and Classroom Connections here.

Linda Deafenbaugh has been developing folklife education learning activities for students and teachers for decades, most recently at FACTS in Philadelphia. She can be reached at lindadeafenbaugh@gmail.com

Endnote

1. Student grammar has been retained from original assessment products throughout this article. This assignment was encouraging written expression—getting ideas down—rather than spelling and grammar.

Works Cited

Deafenbaugh, Linda. 2015. Folklife Education: A Warm Welcome Schools Extend to Communities. Journal of Folklore and Education. 2:76-83.

—-. 2017. Developing the Capacity for Tolerance Through Folklife Education. PhD Dissertation. University of Pittsburgh.

Stephan, Walter and Cookie Stephan. 2001. Improving Intergroup Relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing.