Photo by Sharon Farmer, Courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution.

Zora Neale Hurston, the renowned anthropologist and folklorist, observed in 1934 that “the will to adorn” is one of the primary characteristics of African American expression. Like orature, quilting, and musical forms such as the blues, African American dress and body adornment are creative expressions grounded in the history of African‐descended populations in the United States. They have been shaped by the legacies of slavery, the Civil Rights Movement, and more recent African diasporas. They reveal continuities of ideas, values, skills, and knowledge rooted on the African continent and in the American experience. Most importantly, dress and body adornment are “cultural markers”—aspects of visual culture through which people communicate their self—definitions, the communities with which they identify, their creativity, and their style.

-The Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage Website

The Will to Adorn is a project that began with the idea to work with scholars, educators, students, and cultural practitioners to document the arts of everyday dressing. Dress represents a multifaceted aesthetic tradition closely related to identity, but not often recognized as an art form. Yet, we asked ourselves: What art could be more intimately related to our social and cultural identities then what we wear, how we choose to style our hair, and modify our bodies? What art could be more accessible? In fact, the expressive culture (art form) that is perhaps most closely related to dress is foodways. Everybody needs to eat and everybody gets dressed. What folklorists and other cultural researchers often call the body arts are very personal modes of expression but are also very much connected to a sense of belonging and to the values and beliefs that give meaning to our lives. We present ourselves to others first through the way we dress so the dress arts are both modes of nonverbal communication and performances of our identities. We are all dress artists.

In 2010, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) initiated a research and community engagement project by reaching out to community and academic-‐based researchers, educators, and cultural practitioners. Entitled The Will to Adorn: African American Dress and the Aesthetics of Identity, the initiative focuses on the diversity of African American identities as communicated through the cultural aesthetics and arts of the body, dress, and adornment. It also creates a framework to engage scholars, students, and educators in studying dress as a form of expressive culture shared by communities. The project is grounded in cultural autobiographies of dress. That is to say, the research starts with researchers looking at how they developed their own dress styles as well as the values, beliefs, and skills that determine the way they dress. By asking questions about our own “dressways,” museum, academic, and community scholars, cultural practitioners, and school-‐aged youth collaboratively delve into the community influences on the ways we think about how we present ourselves and our relationships to others through clothing, hair, and personal adornment.

Dress as Autobiography

Given that one of the premises of the Will to Adorn Project is the idea of cultural autobiography, I thought it was appropriate that I share the story of my relationship to dress. I grew up in a family in which dressing well was both an art form and a form of protection. In an age of segregation as a family of African descent in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, my parents deemed it important for us always to be dressed well. After all, we were always being judged by our appearance on the basis of our skin color and the texture of our hair, no matter what we wore. My mother took pride in dressing us as “little princesses” in the best she could afford and had tremendous skill in finding high-‐ quality clothes at a fraction of their retail cost. My father recounts that as a student working his way through graduate school at Columbia University as a hospital orderly he always wore a suit to class. Our family was not alone as African Americans with this consciousness of the messages communicated through dress. It is significant that during the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s marchers and those engaged in civil disobedience were instructed to wear their Sunday best.

My understanding of dress as an art form came as a result of conversations around the dinner table and because many people in my family were what we have come to call “artisans of style.” My mother was a wonderful dresser and taught us to shop for style and value. She was also trained as a hairstylist and apprenticed with an older cousin when she first came to this country as an immigrant from Guyana. As a child growing up on the island of Bermuda, my mom paid for sewing lessons at Ms. Francis’ school because she felt that every young girl should learn to sew. In later years when she opened a dry cleaning business my afternoon chores in the family business consisted of fixing zippers, taking up hems, and other such repairs. So my first grounding in dressways was as an apprentice in the arts of community style.

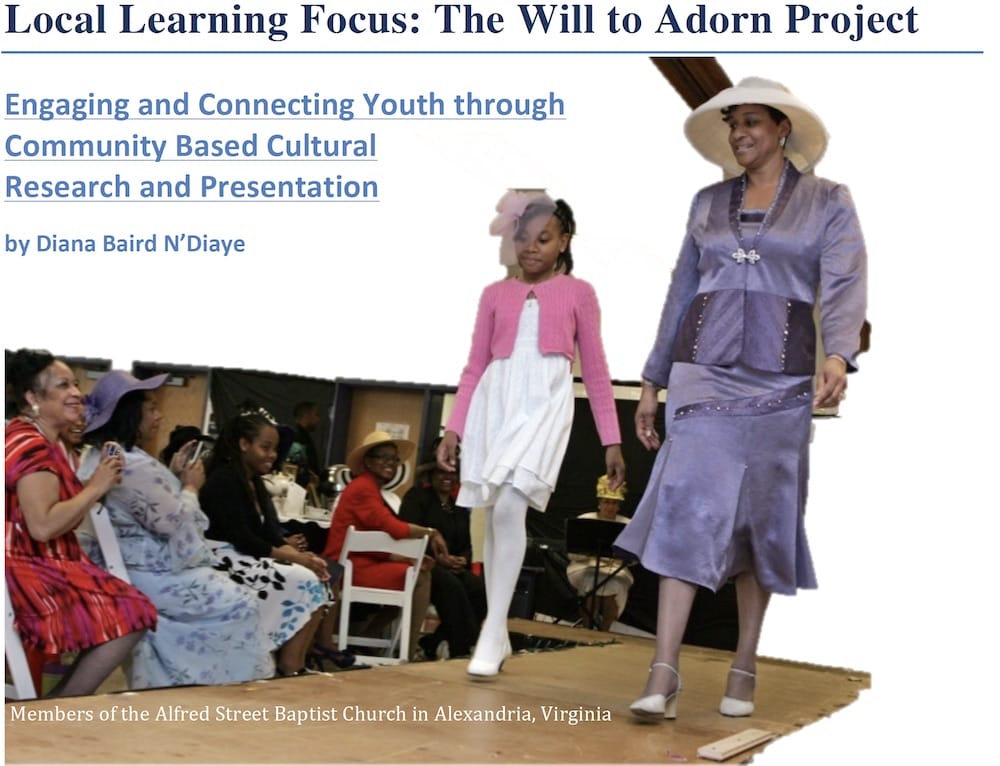

An early appreciation for dress as an art form also came from attendance and participation in what I like to call visual concerts. Churches, schools, and community organizations offer opportunities for people to show off their personal collections of clothing, sense of style, and movement through fashion shows that, like musical concerts, provide entertainment and often raise funds for a common cause. Some of these events are organized by local designers who then use models from the neighborhood or the congregation. These visual concerts are a long-‐standing tradition in African American communities crossing boundaries of ethnicity, faith, and class and generation. At 85 years old, my mother still modeled in fashion shows organized by Bishops Old Girls Association (her Guyanese high school alumni organization) in the United States. More recently, the Will to Adorn Project documented the annual millinery fashion show of the Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, that featured the work of 98-‐year-‐old milliner Mae Reeves along with hats from the personal collections of the parishioners.

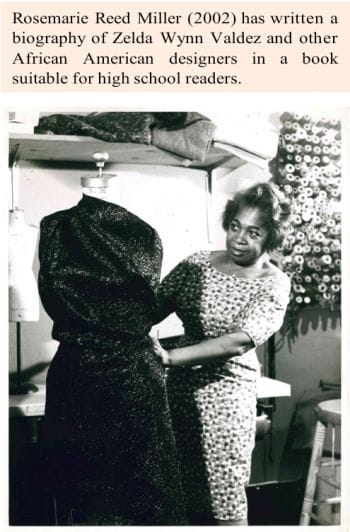

Zelda Wynn Valdez. Courtesy of Dance Theater of Harlem Archives.

Fashion design was my first choice of occupation and I had the good fortune to have wonderful teachers both in my high school and in a community arts program in Harlem. My teacher in the Harlem Program, Zelda Wynn Valdez was an outstanding African American independent designer who created clothing in her salon, on 57th Street and Broadway in New York, for Dianne Carroll, Eartha Kitt, Mae West, Gladys Knight and other glamorous performers. She is also credited with designing the first Playboy Bunny outfit. Ms. Wynn instructed her students in the arts of draping, pattern making and sewing—and in the occupational culture of couture as well. As students we modeled our creations at community events and at the 1967 World’s Fair. I was on the path to becoming an “artisan of style” that would become a lifelong journey.

Nevertheless, a series of chance encounters and my parents’ strong desire for me to get an academic degree led me into anthropology rather than taking on a fashion design major in college— New York University’s Washington Square College, where I was admitted, did not have fashion design as an option so I ended up taking anthropology to learn about the clothing of the world. Although immersed in liberal arts training, I longed to get back to design and when I had the opportunity to begin a master’s program in industrial design at the Pratt Institute I jumped at the chance. I was delighted to discover an entirely new approach to thinking and learning.

In design school, the primary aim was to develop a new set of critical-‐thinking skills. Scientists had the scientific method—creating a hypothesis, testing that hypothesis through research and sometimes fieldwork, analyzing the data, and either confirming the hypothesis or coming to new conclusions based on the disproved hypothesis. As an aspiring designer, I learned another set of thinking skills that allowed students to solve problems in the real world. These skills also included visual literacy. The problem-‐solving aspect of design has been called design thinking. Although the steps of the process have been defined with slight variations, they include defining a problem, researching its contours, brainstorming solutions, creating a prototype, choosing the best of the solutions, implementing or creating, and learning from the creation to define new problems (Rowe 1987).

Folklore and anthropology provide entry points to the study of dress as visual culture, a subject that has become an interdisciplinary field of its own (Mirzoeff 1998). In the Will to Adorn students find ways to think about the cultural expressions related to community dress and style that are meaningful to them and identify those passed on from one person to another person in informal ways. Learning to document the culture in dress working within and with communities allows students to become agents of their own knowledge. We are pleased that the Journal of Folklore and Education focused upon some of the methodologies and the framework for the Will to Adorn Project, and we looking forward to hearing more about how teachers, students, folklorists, community scholars, and artisans of style can create meaningful classroom moments together as they think about dress and culture.

Addressing Educational Standards

The Common Core State Standards stress that students “need the ability to gather, comprehend, evaluate, synthesize, and report on information and ideas, to conduct original research in order to answer questions or solve problems, and to analyze and create a high volume and extensive range of print and nonprint texts in media forms old and new” to be ready for college, work, and life in a “technological society” (2010:4).A folklore-based program like the Will to Adorn can help students achieve college and career readiness by exposing them to alternate worldviews in their own communities. By offering youth the opportunity to prepare for and conduct interviews with artisans in their communities, the project necessarily requires youth to strengthen their ability to analyze written and oral histories, to discern themes within and across interviews, to learn about different vernaculars used to describe the body arts, to write routinely over the duration of the project, and to present informative summaries of complex themes and vocabulary to an audience in a professional setting. All these skills align with the goals of the standards for middle and high school students (2010:39-47).

According to the handbook Folk Arts in Education, “students practice a number of vital technical and academic skills during a community video project,” skills that involve “decoding and word meaning…technical media details, team work or interpersonal relations, performance/public speaking, attention to detail, analysis of oral and written literature… research/planning, critical and analytical thinking… creative/artistic development, [and] language arts” (2008:8).

A Collaborative Pedagogy

While still an undergraduate, I read the work of Paolo Friere, who wrote that:

Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with student-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the one who teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow. (1970:67)

Friere’s ideas about collaborative learning and teaching, how people in disenfranchised communities could learn literary skills, as they created reading materials based on their own experiences, were very important to the development of the methodology for the Will to Adorn and for other projects that I’ve developed. What remains powerful to me in the Will to Adorn project, inspired by Friere’s work, is the validating impact of community and student agency in creating knowledge by documenting and interpreting the shared culture of everyday dress.

We recognize that much directed learning takes place in community settings and venues that offer the flexibility to design curricula that are complementary and supportive of curriculum standards. We also explicitly seek to reach young people for whom the formal classroom is not the learning space one reason or another. These include youth from alternative high schools, heritage schools, faith-‐based groups, and programs for adjudicated individuals.

Alignment with Critical 21st Century Learning Skills

The Will to Adorn Project addresses virtually all 21st century learning skills (see Jenkins 2006), with particular emphasis upon:Distributed Cognition: Learners learn to use common tools, such as smartphones, apps, social media, visual search technology, and webinars “that expand mental capacities.” Collective Intelligence: The Will to Adorn website is built around learning to pool knowledge and compare notes with others toward a common goal.

Transmedia Navigation: Learners use different media resources while processing and presenting their research in public, real-‐time venues.

Networking: Learners gain the ability to search for, synthesize, and disseminate information in the course of preparing for fieldwork interviews by reading and writing blog entries based on their interviews.

Negotiation: Learners interact across diverse generational, ethnic, gender, faith, regional, and occupational communities to document, present, and share their research.

In 2013, CFCH used a combination of online venues, new media, and hands-‐on workshops at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival to take to wider scale this successful program. The project continues to take advantage of new documentation tools such as mobile technology and social media to build 21st century cultural, social, and technical competencies grounded in core skills of literacy, problem solving, critical analysis, and research consistent with education standards. The involvement of partners representing different regions, cultural communities, and age groups is critical to the project’s commitment to identifying, documenting, and representing a range of perspectives and approaches related to dress and adornment.

As educators, studying dress in the classroom or in the community offers wonderful ways to engage students in learning the arts of cultural documentation and analysis of visual culture. Over the five years of the project, we have found that examining dress captures both the imagination of young people and members of the community whom they interview. In interviews completed for the Will to Adorn Project, we hear over and over again from experienced artisans of style about their concerns regarding passing on their skills to new generations and about how meaningful it was to have those skills (including design and entrepreneurial skills) recognized by young people. The pedagogical roots of the Will to Adorn Project are many. They begin with lessons learned from elders at home and in community settings.

The Importance of Teacher Training

Lisa Falk, Arizona State Museum Director of Community Engagement and Partner-‐ ships and contributor to the Smithsonian’s Bermuda Connections guide, emphasizes the correlation between teachers’ investment in folklore projects and the success of the project in the classroom: “[T]he surprise is how something that to me is so obvious – looking at and working with community – is such a new concept to teachers and how excited they become once they do their own mini-fieldwork projects and class presentations. This work creates the difference between liking an idea and adopting and using it back in the classroom” (2004:13).Falk speaks directly to how important teacher training is for getting research-based folklore programs implemented in classrooms. If teachers are given the opportunity to examine their own relationships to their communities, they will be more likely to continue using these techniques in their classrooms, and will ultimately become better equipped to help their students engage with their own identities and communities.

Conclusion

The Smithsonian’s Will to Adorn initiative seeks to understand the relationship between community, identity and the aesthetics of dress. As the research of over four years is affirming, the arts of dress and adornment in African American culture signify more than just a statement of personal taste or a sense of style; they can be understood as examples of artistic expression and mastery. The sheer variety of community dress and body art traditions demonstrates the rich heterogeneity and complexity of the African American population. The Will to Adorn celebrates individual expression and creativity, but it also focuses on the details and conventions of social dressing that define what it means to be well-‐dressed or appropriately attired in different communities.

Diana Baird N’Diaye, PhD, is a curator and cultural heritage specialist at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She conceived and directs the Smithsonian initiative “The Will to Adorn: African American Dress and the Aesthetics of Identity.” Her training in anthropology, folklore, and visual studies and years of experience as a museum educator and researcher working within public schools, along with her lifelong study of the arts of adornment as a designer and studio artist have supported over 30 years of fieldwork, including several award-‐winning exhibitions, educational programs, and publications.

Will to Adorn website for more information:

http://www.festival.si.edu/2013/Will_to_Adorn

Works Cited

Falk, Lisa. 2004. Bermuda Connections: A Cultural Resource Guide for Classrooms. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. http://www.folklife.si.edu/education_exhibits/resources/bermuda_connections.aspx#PDF

Friere, Paulo. 1970. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. M. B. Ramos, Trans. New York: Herder and Herder. Miller, Rosemary E. Reed. 2002. The Threads of Time, the Fabric of History: Profiles of African AmericanDressmakers and Designers from 1850 to the Present, 2nd Edition. Washington, DC: Toast and Strawberries Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006 Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education of the 21st Century. http://www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/resource/2713

MacDowell, Marsha and LuAnne Kozma. 2008. Folk Arts in Education: A Resource Handbook II. Michigan State University Museum. www.folkartsineducation.org

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 1998. The Visual Culture Reader. New York: Routledge

N’Diaye, Diana Baird. 2013. The Will to Adorn: African American Diversity, Style, and Identity. InSmithsonian Folklife Festival Program Book, 27-‐31. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. 2010.

Common Core State Standards. Washington D.C.: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy

Partnership for 21st Century Skills http://www.p21.org

Rowe, Peter G. 1987. Design Thinking. Cambridge: The Massachussetts Institute of Technology Press. Smithsonian Institution, Education and Outreach. 2013. Youth Access Program Guidelines.Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.