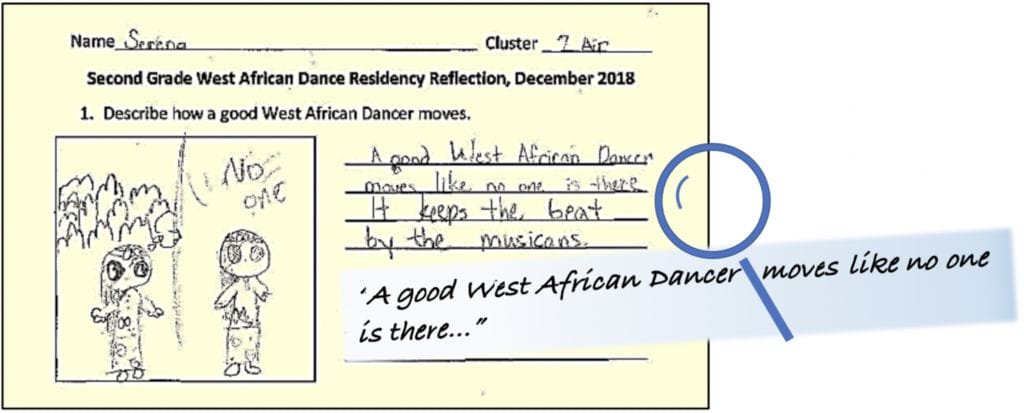

West African Dance Reflection Sheet, by Serena, a 2nd grader. All photos courtesy Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School unless otherwise indicated.

As the field of education offers more inclusive learning environments for students from different backgrounds—for example, cultural, socioeconomic, and neurological, to name a few—providing alternative education models challenges the “one-size-fits-all” approach in conventional classroom education (Brickmann and Twiford 2012, Friend and Cook 2016, Gay 2018, Pratt 2014). Such models include push-in special education support, small-group special education classes, multi-age classes, virtual classroom teaching, education residencies, station teaching, apprenticeships, culturally responsive teaching, and co-teaching.

Although alternative education models are often advocated as new means to support higher academic achievement, folk arts pedagogy has used and/or modified these models for years. Consider an African dance class at a community center in West Philadelphia. You walk in and see 20 students. At the front sit two dancers and seven drummers who share an air of collaboration. You hear grunts of determination; hand clapping; and the polyrhythmic slap, tone, and bass of the djembe. In fact, you FEEL the sounds of the djembe in your chest. In this scenario, a typical example of a community dance workshop, we experience “alternative” education.1 The multiple teachers guiding the dancers through the steps demonstrate one co-teaching model: team teaching. You see small-group support when one dancer takes two or three students aside to work through a movement. Older students mentor newer students, another alternative teaching model. In the community, examples of alternative assessment strategies exist as well, such as evaluative feedback, self-reflection, and performance critique discussions. These examples contrast with schools’ reliance on formal assessment, grades, tests, and academic competition.2 Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS), in the Chinatown neighborhood of Philadelphia, is a prime example of an institution that values alternative learning environments and methods and invites community knowledge and ways of knowing into the school (Deafenbaugh 2015). An excellent illustration of the FACTS curriculum approach is the West African dance residency. It is a collaboration between the FACTS music teacher and a community teaching artist and African dance expert. This article presents a closer look at the intersection of three educational models employed during a West African dance residency in an elementary music classroom: co-teaching, pedagogy focused on folklife and folk arts, and teaching artistry.

Co-Teaching, Folklife Pedagogy, and Teaching Artists

by Avalon

Friend and Cook (2016) define co-teaching as the partnering of two (or more) teachers for the purpose of cooperatively delivering instruction to a group of students. Although abundant documentation of co-teaching addresses classroom inequalities, less documentation systematically outlines how co-teaching can affect and increase student understanding in a “specials” classroom.3 In this co-teaching model that I am offering as a case study, it is important first to articulate the role of each teacher. The bearer of community knowledge was Jeannine Osayande, an African American dancer, Ghanaian cultural expert, and my teaching partner for a FACTS West African Dance Residency between 2016 and 2018.4 I am an academically trained music educator, and I am specifically interested in co-teaching because it is one of the most authentic, and perhaps exciting, ways to integrate folk arts residencies into a general education classroom. Part of my responsibility in hosting this residency is ensuring that my classroom is a safe environment that treats cultural art forms with respect and authenticity. In making clear our roles, there is also a certain dedication to equity between teachers: Our respective strengths influence the teaching that takes place.

Teaching artists at our school include professional and community artists who teach and integrate their art forms into educational settings. They teach others their art form and do so through their own way of knowing or doing it. In other words, there is something else to learn from creating the art besides completion. It is not within the scope here to document Jeannine’s extensive background as a dancer and teacher—that would be an article in its own right! Rather, I seek to illuminate the ways in which FACTS students inextricably gained a unique, meaningful learning experience because of Jeannine’s knowledge and presence in my classroom. Including a community artist in the classroom helps bridge the gap between learning about an art form and learning to do an art form. Jeannine frames this residency to illustrate how seemingly unconventional curricula can indeed become more customary over time and how her work helps to break down systemic racism in education.

Ago and Ame

We borrowed the call-and-response words ago and ame from the Twi language of West Africa. Any member of the community may use ago if they need to get the attention of the group. Ame is the response that acknowledges a willingness to listen. Not only does this call and response demonstrate respect for other members of the classroom, it also offers an example of the cultural borrowings that honor cultures of the African Diaspora in the development of a multicultural classroom community (Richards 1996, 41).

Decolonizing the Curriculum with Jeannine Osayande & Dunya Performing Arts Company

by Jeannine

An untraditional curriculum becomes a forward-thinking traditional curriculum (i.e., becomes convention) when long-term collaborative teaching relationships develop between teaching artists and classroom teachers. Over the past 28 years, Swarthmore Rutledge School, Germantown Academy Lower School (for 21 years), and Westtown Lower School (18 years), have collaborated with Jeannine Osayande & Dunya Performing Arts Company. These co-teaching relationships “provide the ability for an integrated multicultural experience into [sic] the classroom’s curriculum and stimulate students to think critically about their experience in society” (Patrik 2005, 100). Through her instruction of Diaspora West African dance, storytelling, drum, and song traditions, Jeannine’s participants examine critically the significant polycentric part(s) we hold in our communities as an individual and as a member of a group. Polycentric means “having multiple centers.” In the Diasporic drum and dance cultural traditions, this African aesthetic is significant in our relationship to the cosmos. We have multiple centers, while we hold down different parts. Polycentricism is “motion spending time, the occupant of a time frame and not the moving from point A to point B.” As it regards the body of the dancer, “the polycentric sense allows for both slow and fast (all within the same time frame), with the movements coming from several different directions.” In other words, “the representation of the cosmos in the body is a goal” and movement can originate from any part of the body (Asante and Welsh Asante 1990, 74-5). Our artist-in-residence program invites classroom teachers, students, administrators, and cultural experts to a collaborative opportunity to have a voice in decolonizing the curriculum. The Keele Manifesto for Decolonizing the Curriculum (2018) asserts, “Decolonizing is about rethinking, reframing and reconstructing the current curriculum in order to make it better, and more inclusive. It is about expanding our notions of good literature so it doesn’t always elevate one voice, one experience, and one way of being in the world. It is about considering how different frameworks, traditions and knowledge projects can inform each other, how multiple voices can be heard, and how new perspectives emerge from mutual learning.” In decolonizing the curriculum, Jeannine Osayande & Dunya Performing Arts Company ask these essential questions:

What kind of friend are you?

What are Africa’s gifts and contributions to the world?

Where do you see Africa in your everyday life?

The company’s vision is to radiate joy and seek out collaborative experiences that manifest beauty: “Our mission is to add value to our environment and community through arts, culture and social change”.5 By digging into the co-teaching process, Avalon and Jeannine seek to present practical considerations that could inspire other educators to identify community artists and experts in the cities and towns where they teach and to initiate collaborations with them that are designed to address racial and cultural barriers in the classroom better.

Methodology

by Avalon

Jeannine’s influence shifted FACTS’ residency focus to provide students specific insight into Ghanaian culture through the stories and movement of Kpanlogo, a contemporary dance from the Ga-dangbe people.6 I was inspired to write this article after the 2018 residency, our third year working together. Although I am the primary author, Jeannine has contributed by graciously allowing me to describe our partnership, providing resources to further my understanding of Ghanaian culture, and offering invaluable thoughts and passages. We have different strengths as educators, and I have learned a lot working with her. Post-residency reflection has helped me to explain why we work so well together, what from our partnership can be replicated in other residencies or co-teaching relationships, and how a cultural art form remains authentic even in a school setting.7

I used autoethnographic research methods to examine the development and execution of instruction and discuss the potential effect this teaching partnership had on both student understanding and teachers’ professional development. Data includes video recordings of classes from 2017 and 2018, typed notes and audio recordings from 2016-18 planning and reflection sessions, and supplemental and reflection worksheets developed for students over the history of this residency. Linda Deafenbaugh, the FACTS Folk Arts Education Specialist, recorded most of the classes and scheduled, guided, and recorded all meetings between the teaching partners over the course of this residency. She also coordinated professional development workshops about folk arts pedagogy for teachers and data collection for all residencies and ensembles that take place at FACTS. Jeannine and I spoke over the phone and met in person numerous times during the course of writing this article.

The FACTS student body consists of 512 students. Approximately 68 percent are Asian American, and 12 percent African American. The remaining are Hispanic (5 percent), Multiracial (8 percent), and White/Non-Hispanic (7 percent). In this residency, we worked with 56 students, split between two 2nd-grade classes (Class A and Class B). Almost all 2nd graders had attended FACTS since kindergarten and were accustomed to weekly choir and music classes. The 2018 residency occurred during regularly scheduled back-to-back music classes on Friday afternoons from September 28 through December 14.

Our Co-Teaching Methods

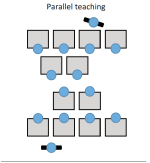

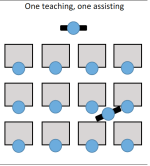

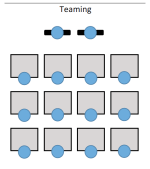

Most teachers aspire to have a strong collaboration with their teaching partner, yet our partnership went above and beyond that usual desire for success. Jeannine recently remarked that our partnership felt special from the very beginning because of our intention to “humble ourselves to each other’s expertise.” In other words, we were dedicated to rethinking instruction in a way that best used our different teaching skills from day one. Many publications centered on co-teaching discuss the ways co-teachers can use systematic teaching and reflection methods to create a strong professional bond. Interactions: Collaboration Skills for School Professionals (Friend and Cook 2016) lists six main co-teaching methods: 1) one teaching, one observing; 2) station teaching; 3) parallel teaching; 4) alternative teaching; 5) teaming; and 6) one teaching, one assisting. Jeannine and I did not approach our partnership by coordinating which of Friend and Cook’s methods to use; rather, post-residency reflection and video analysis revealed that we primarily used three of their methods: parallel teaching; teaming; and one teaching, one assisting. It is instructive to consider how each interaction was engaged in the classroom to facilitate learning.

*Images of co-teaching created by Avalon to illustrate Friend and Cook (2016) approaches.

Parallel Teaching*

The Adinkra symbol Mpuannum, or “five tufts of hair” (Korankye 2017) is the starting formation for a dance Jeanine was teaching. She was instructing students to arrange themselves into five separate circle groups, arranged like Mpuannum (Figure 1). This connection between their physical arrangement and the symbol was intentionally not made clear to students during this particular lesson; they discovered the connection organically. Students were guided to notice similarities between their dance formations and Adinkra symbols in a later class. This “discovery-learning” process was emphasized in this residency; we believe it reinforces student ownership and excitement. Jeannine and I walked around the room and held up our hands, instructing small groups of students to make circles around our bodies, and then sit on the floor. The performance starts when a teacher begins the call-and-response song, “O Shei Baba8,” and the drumming ensemble begins to play. This formation was later transformed into one large circle; as the students do hand rhythms in their small circles, they are called to join, one by one, the central circle, without missing a beat.

While teaching this lesson in 2017, we noticed students found it challenging to recreate this figure from verbal direction alone.9 Jeannine then drew the formation on the board, but only a few more students understood the formation. Later in the same lesson, I walked over to a location that would be the center of one group’s circle, put my hands up above my head, and said, “When I say go, group one will join hands in a circle around me…GO!”10 The students were successful, and Jeannine then copied my procedure. It is essential to the success of lessons within a residency to remember moments like this. We recalled during the planning and goal-setting meeting for the 2018 residency that we should incorporate this formation by using the previous year’s most successful procedure. A general feeling of trust allows teachers to adjust procedures spontaneously, especially if they diverge from the original lesson plan.

Figure 2. Parallel Teaching Approach. Throughout this class, Jeannine and Avalon moved around the room simultaneously to teach the same dance move to small groups of students (11/16/18).

One Teaching, One Assisting

One Teaching, One Assisting

I noticed from informal observation and review of video recordings of our lessons that Jeannine did a lot more talking and demonstrating than I did during the first weeks of the residency (when much of the information is completely new to the students). By the 2018-19 school year, I had hosted this residency four times. Because of the value FACTS places upon developing residencies that repeat and deepen each year, I know how the residency will pan out, what dance moves Jeannine was planning to teach, and how to help students efficiently. Regardless, the pattern of unequal contribution does seem like the most appropriate option at the beginning of any folk arts residency, as the expert bearer of cultural knowledge should be the primary teacher. Not only does this process allow students time to get acquainted with the teacher, it also reflects the classroom teacher’s respect for the teaching artist and their way of teaching. In the videos showing the one teaching, one assisting method, Jeannine was at the front of the room demonstrating a move for the students, while I modeled student behavior (such as tracking the teacher and mirroring dance moves) or assisted students who needed extra help or redirection (Figure 3). This further illuminates Jeannine’s comment about how we were each “holding down our part” from the very beginning.

Figure 3. One Teaching, One Assisting/Observing Approach. In this class, Jeannine primarily led dance instruction and Avalon primarily modeled student attentiveness and reinforced behaviors (10/26/18).

“The teaming model has been referred to as the most collaborative model of team teaching, as it demands the greatest amount of shared responsibility” (Baeten and Simons 2014, 95).

Team Teaching

Team Teaching

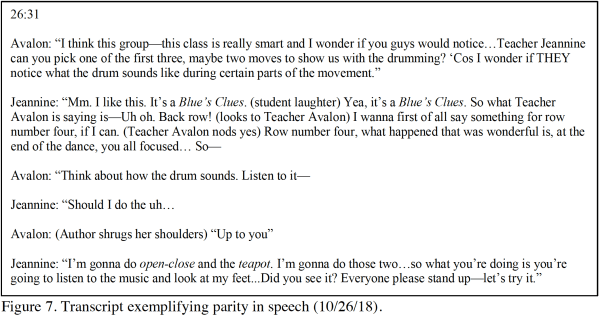

The majority of our teaching style could be defined as team teaching. Jeannine and I developed a strong partnership from our years of working together and understanding each other’s strengths. In fact, Jeannine and I had a special connection from the beginning; it is difficult to define, but our personalities really just mesh. Teaching as a team seemed to be the most natural to us: “Go for teaming when co-teaching partners really hit it off; synergy and parity make or break this approach” (Ploessl et al. 2010, 162). When it is done well and is appropriate to implement, I believe team teaching is the most satisfying for both the students and the teachers. It is important for both teachers to have a sense of ownership in the residency they create together (students notice when teachers love what they are teaching). In the latter half of the residency, when our teaching style was almost exclusively team teaching, weekly classes resembled rehearsals. First, Jeannine announced at the beginning of the residency that I was in charge of leading song (“You’re the better singer”) and she was in charge of leading dance.11 She also asked me to drum in the 2018 residency, which is the authentic way of teaching African dance: one (or more) dance instructor(s), one (or more) drummer(s)/musician(s). I am not a trained African drummer, yet I was able to pull it off for rehearsal. This role allowed me more presence in the residency, whereas in past residencies I have adopted a role closer to that of a classroom “disciplinarian.” In this case, the shared responsibility from team teaching helped to reinforce our mutual desire to make the residency as successful as possible, even without sufficient funding to have an African drummer. Jeannine and I shared the responsibility of dancing and demonstrating moves, guiding student formations, and playing auxiliary instruments. It should be clear by now that our roles were different (and changed over time) primarily because of preexisting educational strengths. Equity between co-teachers is achieved when teachers teach to their respective strengths and learn from and trust each other (Ploessl et al. 2010, Pratt 2014).

A pattern of role switching emerged over the course of the residency. Our 2nd-grade classes are back to back on Friday afternoons and each is 52 minutes. We typically replicate the lesson for the second group, as was exemplified in lesson procedures and teacher language.12 But I found, upon watching the videos, that we would usually switch roles for the second group. For instance, if I gave the rundown for today’s lesson plan in class A, Jeannine would give it in class B. In fact, multiple activities within each lesson were reversed for the following hour of teaching. Although our switch of responsibilities was unplanned, Jeannine was mindful in making sure that both teachers shared the opportunity to lead within the team teaching format once the pedagogy and cultural knowledge were established in the first weeks. Jeannine describes this switching as a type of (teaching) improvisation. Role switching, planned or unplanned, is a clear example of professional familiarity and respect and of modeling professional development techniques for educators (Brickman 2012, Pratt 2014). It was intentional that Jeannine gave me permission to help teach her cultural knowledge, and I gave her some tools for student-appropriate redirection, modeling, and language. We were consistent in keeping each other accountable for our actions and language and doing so in respectful ways.

Figure 4. Team Teaching Approach (11/30/18).

The Role of Drumming

by Jeannine

Avalon’s drumming contribution was invaluable to the African dance residency. She eagerly played the Kpanlogo basic rhythm pattern while I played the 6/8 rhythm on the Gangokui double-headed iron bell. The relationship of live drumming with African dance is paramount; this drummer/dancer relationship is integral to the cultural tradition being taught. Because we lacked funding for a lead drummer, our skills had to make do. A DunyaPAC/FACTS drummer, Steve Jackson, Sr., was able to teach two 30-minute drum lessons in the beginning of the residency. These lessons were helpful: Avalon and I were able to provide basic drum accompaniment to our weekly lessons from then on. The students embraced the rhythm, motivated to move. The FACTS African Diaspora Drum ensemble, taught and led by Steve, accompanied our final dance rehearsal and the performance. The question remains: What would this residency have looked like if we had the funding to do it authentically, with a professional drummer, every week?

There are not sufficient funds to hire a drummer for every session of this residency. With my input, FACTS administration decided to integrate the middle-school African Diaspora Drum ensemble with this West African dance residency. Scheduling the residency and ensemble to meet at the same time made it possible for the drum ensemble to drum for the dancers’ final rehearsal and the final performance, but not in every rehearsal. The African Diaspora Drum ensemble were taught the Kpanlogo rhythm in only a few sessions before the final performance; their motivation and performance were admirable, but this is not the culturally authentic way of bringing drums to the dance experience. In not closely examining the art form (and its necessary components), funders can unintentionally uphold practices rooted in systemic racism and white privilege. The lack of sufficient funding to hire a professional African drummer to be present in every session of our African dance class is problematic for teaching the tradition authentically. These seemingly minor funding decisions can directly change how a cultural tradition is practiced and presented. Ultimately, funders should consider carefully how insufficient funding contributes to dismantling traditions, like African drum and dance, by funding one part and not the other.13

Teacher Language

by Avalon

While analyzing videos, I looked for differences in teacher language. Our differing cultural and educational backgrounds are confirmed by our use of fairly distinct attention-getting techniques. In a typical classroom setting, attention-getting techniques are audible cues to alert students to discontinue conversation and listen to the teacher. Jeannine primarily used the call “Ago” (meaning Are you listening?), to which students respond “Ame” (meaning Yes, you have my attention). I typically used a technique of call-and-response-style clapping, a common FACTS practice. Additionally, we both used chanting techniques (1, 2, 3, eyes on me… 1, 2, eyes on you!) and, infrequently, a countdown technique. Figure 5 presents the frequency of both teachers’ use of their primary attention-getting techniques. The data does not reveal efficacy of any techniques, but it does show that the teachers’ verbal cues changed over the course of four weeks. I never used the terms Ago/Ame to get students’ attention, just as Jeannine never used the clapping technique, yet there is a slight increase in frequency of Ago/Ame as the lessons progressed.14 Contrarily, there is a slight decline in frequency of my clapping technique, as well as our use of the countdown technique, as the lessons progressed. The increase in frequency of Ago/Ame suggests that Jeannine’s role in classroom management likely increased over time. Students are interacting with and responding (with success) to our differing language styles, and occasional code switching, multiple times every single class.

| Date | Class | Ago/Ame—Jeannine | Clapping Signal—Avalon | Countdown—Jeannine or Avalon | Other (Chants, Chime) |

| 10-26-18 | B | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| 11-02-18 | A | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 11-02-18 | B | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 11-16-18 | A | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| 11-16-18 | B | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 11-30-18 | A | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 11-30-18 | B | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

Figure 5. Frequency of attention-getting techniques.

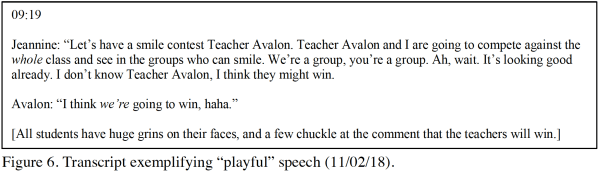

Jeannine and I had more playful interactions and informal language while team teaching. In fact, the atmosphere seemed more fun when we used team teaching over other co-teaching models. Noticeable smiles and laughter from students and the occasional exchanging of jokes between the teachers characterize an atmosphere of fun. Figure 6 is a selection of a transcript from a lesson that exemplifies the informality of our speech with each other. Informal language does not diminish the success of the student-teacher relationships. I argue that intercultural competence within an elementary classroom setting relies simultaneously on culturally AND age-appropriate speech—and age-appropriate speech for 2nd graders includes playful interactions and jokes.

Students should view co-teachers as equals, regardless of relative classroom teaching experience (Brinkman and Twiford 2012, Friend and Cook 2012). In fact, student learning is enhanced because teachers “bring different things to the table.” Professionals who interact with students and colleagues from diverse backgrounds are engaged in what is called intercultural competence, or the “ability to function effectively in culturally diverse settings” (Günay 2016, 409). Therefore, it is the responsibility of teaching partners to encourage first an atmosphere of respect and intercultural competence with each other and, in turn, foster respect from students. In watching our lessons, I looked specifically for examples in our speech and body language that demonstrated tools of intercultural competence. Our students subconsciously gained valuable social skills simply from observing two adults (with widely different cultural backgrounds) coming together harmoniously to teach one subject. Parity is achieved because Jeannine and I shared the responsibility of teaching and redirecting behaviors and developed healthy communication skills during and after teaching. Furthermore, Alfdaniels Mabingo suggests that participating in African dance is a type of civic engagement (in our case, for FACTS 2nd graders) that undermines stereotypes about the continent of Africa: “…teaching African dances can lead to perceptual and attitudinal changes about Africa” (2018, 107). We believe intercultural competence is reinforced within multiple layers of this residency—for both the facilitators and the participants.

Developing an effective co-teaching partnership takes work to learn each other’s communication styles, teaching styles, and even a little about personal lives (Baeten and Simons 2014, Pratt 2014). Here, reflection is paramount in effecting change in teaching behaviors (Kerin and Murphy 2015). I believe the success in my partnership with Jeannine is due in part to our dedication to these concepts. We spent time outside the classroom to learn about each other’s lives and teaching experience. In planning meetings, we took extra care to ensure each was able to share everything she wanted to share; no one was excluded or interrupted. In situations when co-teachers are not as lucky as we were to become friends, they should do everything in their professional power to respect and learn about each other, as friends would do.

Developing an effective co-teaching partnership takes work to learn each other’s communication styles, teaching styles, and even a little about personal lives (Baeten and Simons 2014, Pratt 2014). Here, reflection is paramount in effecting change in teaching behaviors (Kerin and Murphy 2015). I believe the success in my partnership with Jeannine is due in part to our dedication to these concepts. We spent time outside the classroom to learn about each other’s lives and teaching experience. In planning meetings, we took extra care to ensure each was able to share everything she wanted to share; no one was excluded or interrupted. In situations when co-teachers are not as lucky as we were to become friends, they should do everything in their professional power to respect and learn about each other, as friends would do.

“Recognize that cultural differences are complex structures that deeply affect not only customs and attitudes but also how different co-teaching partners perceive the same situation. Make time to share personal stories and narratives. These conversations convey partners’ culturally driven value and belief systems, helping to build a safe and trusting climate” (Ploessl et al. 2010, 165).

Materials

Jeannine and I used a variety of materials to aid in planning the residency, setting goals, and providing structure for students during each lesson. Most are far from anything that would be used in an authentic setting like community African dance classes, and especially dance experiences in West Africa.15 Yet the materials we used are a necessary part of creating meaningful instruction in a conventional elementary school setting. Reflection materials allow teachers insight to students’ understanding, and student responses illuminate what part of the residency is most memorable and effective. Linda developed the majority of handouts and supplementary materials for this residency. I highlight a few of the more successful tools to inspire other educators to think about how conventional educational tools can help integrate folk arts pedagogy in public schools.

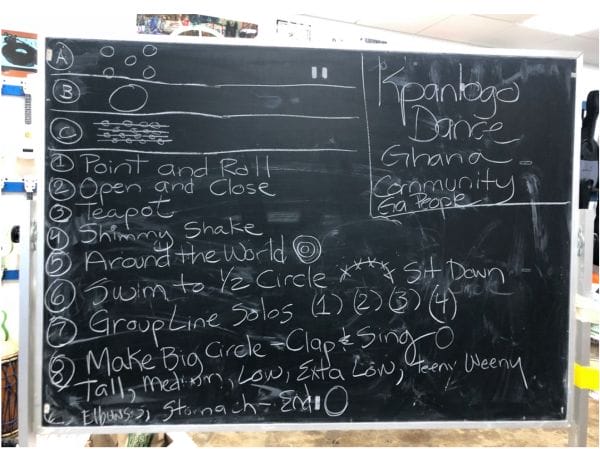

Figure 8. Daily chalkboard (12/3/18).

The daily chalkboard outlines the steps for that day’s lesson and a bird’s-eye view of the dance formations. We started using this setup from the first day of the 2018 residency, allowing students to track the visual progress of the choreography and give them hints for the next move if memory failed them (Figure 8). On the chalkboard the reader sees Jeannine’s dance book notation style, which reflects how she organizes and internalizes content through words and drawings of the choreography.16 I suggested using the chalkboard as a visual aid during the 2017 residency when I noticed students’ difficulty remembering the steps from the previous week’s lesson, and I was, admittedly, having difficulty remembering the trajectory of our lesson. We adopted this tool from then on. So the “chalkboard” tool was borne out of necessity; if we had the opportunity to meet for this residency more than once a week, students would be better equipped for rote learning the dance. We also took informal pictures of the board (with a cellphone) after each week’s class to reference for the next lesson.

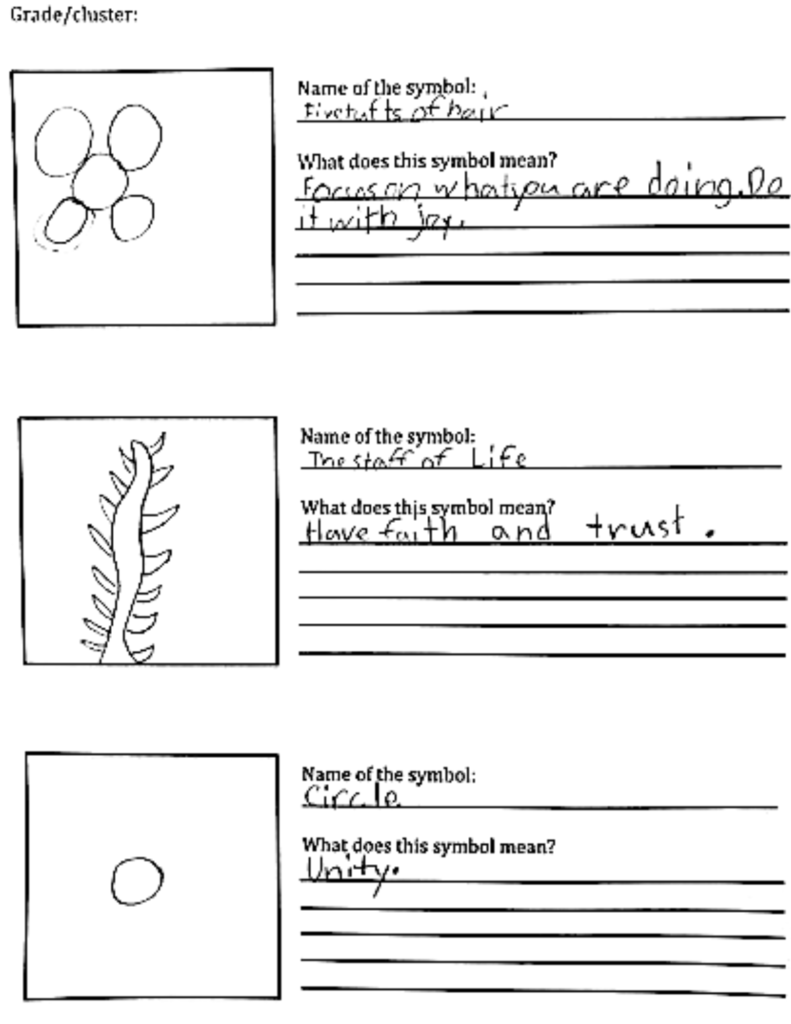

To deepen student understanding, we also needed to address the deep cultural context of the dances being learned in the music classroom. Folk arts provide ample opportunities to connect with other specials, as well as the general education classroom, because of the significant cultural contexts that these arts engage. In our case, Linda launched an Adinkra cloth sub-unit within the 2017 residency. Adinkra symbols are visual connections to proverbs and significant values within the Akan culture of Ghana, West Africa (Inscribing Meaning 2007). This sub-unit included showing 2nd graders a video of FACTS’ 8th graders creating the cloth for the 2nd graders’ final dance performance and teaching students the meaning behind Adinkra symbols. In one example, Jeannine and I held up student-created fabrics and asked the 2nd graders, “Is there anything on the fabric that reminds you of our dance?” One student connected the dance movement we referred to as “around the world” with the Adinkrahene: “That one looks like ‘around the world’” (Figure 9).17

In the 2018 residency, we created a new homeroom classroom activity in which students looked at African fabrics to locate Adinkra symbols, match symbols on the fabric with those on a worksheet Jeannine created, and redraw the symbols, with their respective meanings, on a separate worksheet. We may infer that this small project influenced student understanding of the connection between the Adinkra and the dance; one student commented, “We wore [the cloth] because it meant peace. And it showed we really know African Dance and understand.”

In the 2018 residency, we created a new homeroom classroom activity in which students looked at African fabrics to locate Adinkra symbols, match symbols on the fabric with those on a worksheet Jeannine created, and redraw the symbols, with their respective meanings, on a separate worksheet. We may infer that this small project influenced student understanding of the connection between the Adinkra and the dance; one student commented, “We wore [the cloth] because it meant peace. And it showed we really know African Dance and understand.”

Figure 10. Zoey’s Adinkra Worksheet.

At the end of this residency I modified an existing reflection template to generate a post-residency reflection worksheet for 2nd graders. The reflection sheet included age-appropriate questions and places for both written answers and drawings. The reflection process is important to the integrity of the residency programs and should be integrated into the curriculum with respect and intention. I was able to carve time out of two music classes, following the final residency performance, to allow students a total of 50 minutes for reflection. Students were encouraged to talk to each other during the reflection process.

Deepening Understanding and Next Steps

The most effective co-teaching partnerships are characterized by a dedication to reflection of student achievement and teacher satisfaction following every co-taught lesson (Ploessel et al. 2010, Pratt 2014). In each FACTS residency, the general education teacher and teaching artist sit down and plan the goals of the residency and materials to track progress. We also have a post-residency meeting to assess successes and address areas of concern. Jeannine and I had informal weekly check-ins. We would reflect for 15 minutes each Friday afternoon following our last class to discuss questions: What went well during the lesson? What did not go well during the lesson? What are we going to teach next week? Future partnerships in this particular residency might be more successful with more consistent, standardized reflection. Teachers may use a reflection checklist or follow a stricter regimen of written reflection, through email.

Figure 11. Front and back of West African Dance Reflection Sheet, with typed transcriptions. From Serena and another 2nd grader.

Likewise, hosting student interviews would allow additional honest and comprehensive student responses. Such an extension could provide an opportunity to link to other curricula within the school. For example, older students might interview younger students’ residency experiences as a project for a unit on interviewing skills. Further research and more systematic data analysis is warranted to explore the qualitative differences of teaching partners’ language and evidence of student understanding as illuminated by student reflections.

The culturally responsive co-teaching frame is more important now than ever, amid significant changes in educational practices in public schools and the globalized world our students live in (and have more access to each day). I hope educators reading this article can reimagine their classroom as a safe space to include diverse voices intentionally, especially those typically left out of conventional educational models, and recognize the power of connecting school and home life. In other words, school and community ways of knowing need not be mutually exclusive (Deafenbaugh 2015). It takes more than an “open mind”—teachers need to be actively looking at the communities in which they teach for ways to integrate community and home life with school life. Educators can bridge the gap to make education more culturally responsive and equitable; this effort requires a dedication to being truly reflective and critical of their own work and to bringing in community voices: “However important they are, good intentions and awareness are not enough to bring about the changes needed in educational programs and procedures to prevent academic inequities among diverse students. Good will must be accompanied by pedagogical knowledge and skills as well as the courage to dismantle the status quo” (Gay 2018, 14).

For our fellow educators, ask yourself: How am I helping my students engage appropriately with the world when they can just as easily conduct a Google search on their tablets? How am I guiding my students to learn from their community and find value in their own cultures? How can learning an art from outside my students’ cultures inform their understanding of the importance of folk arts in societies? I think this residency is at the forefront of change in education, and I hope it excites other teachers to consider how their teaching addresses the equity between school and community knowledge. Other educators can use my partnership with Jeannine as a framework for developing their own partnerships with other teaching artists, folk artists, and cultural experts. I encourage educators to think about how co-teaching opens up the door for equity in education and helps connect best practices in cultural pedagogy to the public school classroom. The respect that Jeannine and I have for each other as remarkable educators and talented artists not only created a safe and productive learning environment for our students, it also created a magical atmosphere that helped us each become better at what we do.

For our fellow educators, ask yourself: How am I helping my students engage appropriately with the world when they can just as easily conduct a Google search on their tablets? How am I guiding my students to learn from their community and find value in their own cultures? How can learning an art from outside my students’ cultures inform their understanding of the importance of folk arts in societies? I think this residency is at the forefront of change in education, and I hope it excites other teachers to consider how their teaching addresses the equity between school and community knowledge. Other educators can use my partnership with Jeannine as a framework for developing their own partnerships with other teaching artists, folk artists, and cultural experts. I encourage educators to think about how co-teaching opens up the door for equity in education and helps connect best practices in cultural pedagogy to the public school classroom. The respect that Jeannine and I have for each other as remarkable educators and talented artists not only created a safe and productive learning environment for our students, it also created a magical atmosphere that helped us each become better at what we do.

Avalon Brimat Nemec is pursuing a Masters in Music and Human Learning from the University of Texas at Austin. She holds a Bachelor of Music degree in Music Education from Temple University, where she studied French horn. She was the General Music and Choir teacher at Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School in 2014-15 and 2016-19. She now teaches general music at UT’s String Project.

Jeannine Osayande has been a choreographer and master movement and teaching artist of Diasporic West African dance and drum traditions for 38 years. She holds a BA in Anthropology from Temple University, Traditional and Contemporary African Dance Certification from Noyam African Dance Institute and the Ghana Board of Education, and Teaching Artist Certification from Columbia University Teachers College. Her Diasporic African teachers/mentors include De Ama Battle, Ibrahima Camara, and F. Nii-Yartey. She is owner/director of Dunya Performing Arts Company and on the roster of Young Audiences of NJ and Eastern PA.

Endnotes

1 This example describes an education experience that is alternative to typical public schooling, yet core within the context of folk arts pedagogy.

2 It is worth mentioning, in participatory art forms—e.g., West African dance—value is placed on participation rather than presentation. Success is measured by the inclusivity of the experience. This is somewhat contrary to westernized music and dance experiences in public schools, where the final performance is the most important aspect for evaluating the success of the experience (Turino 2008).

3 “Specials” refer to Music, Physical Education, Art, and Foreign Language subjects, typically considered by public schools to be extracurricular to core academic subjects.

4 Jeannine and Alexis Adams, the current music teacher at FACTS, worked together on this residency for the 2019-20 school year.

5 Jeannine Osayande, email message to Avalon Nemec, July 15, 2020.

6 Kpanlogo (PAHN-loh-goh) is a recreational dance and music form from Ghana, West Africa. It was first played by the Ga-Adangbe people, most of whom live in and around the capital city, Accra. Kpanlogo can now be seen on national and international stages. The rhythm, songs, and dance became popular among youth during the Pan African and African Independence Movements of the late 1950s but is based on ancient drumming patterns that “contain musical motifs borrowed from older Ga pieces like Gome, Kolomashie, and Oge, as well as highlife.” Kpanlogo: Background and History. n.d. Accessed May 14, 2020, https://thisworldmusic.com/kpanlogo-african-drumming-dance-ghana.

7 Consider that teaching a cultural art form (as opposed to teaching about a cultural art form) is cultural appropriation without the voice of the community member.

8 This song is Kpanlogo from the Ga people of Ghana. The full title is Baba baba shie baba OO, O shei Baba. Jeannine learned the song from Professor F. Nii-Yartey, Ghana National Dance Company, Noyam African Dance Institute, Ghana Dance Ensemble. For more information see, https://www.potsdam.edu/sites/default/files/West%20African%20drum%20and%20dance%20ensemble%20on%2011%2020%2016.pdf; http://africandrummingclub.blogspot.com/2005/08/what-we-play-kpanlongo.html; and https://youtu.be/AHTBjasyiWo.

9 This was discussed anecdotally in the 2018 pre-residency planning session.

10 Anecdotal approximation of a quote.

11 Jeannine directly said on multiple occasions before classes that she preferred my singing voice for modeling.

12 In analysis, I observed these mirrored language and lesson progressions in videos of lessons that were taught on the same day.

13 FACTS administration recognizes this is not the optimal teaching and learning situation for this tradition, yet this compromise prevented other significant arts residency cuts. The authors appreciate everyone’s efforts to rectify this problem and believe we did everything in our power to make the residency successful and engaging. We acknowledge that the funders didn’t intend to disenfranchise the cultural tradition because of lack of funding; however, the effects are felt either way. During a time of national protest and the Black Lives Matter movement, it is important to have these conversations.

14 Interestingly, Ago/Ame was not uttered a single time in one class early in the residency.

15 The term “experience” is intentionally vague in this context. It is not necessarily culturally appropriate to refer to dance as an instructional experience.

16 Jeannine carries this learning tool from the FACTS school residency into her teaching practice. She writes her choreographic notes and movement sketches on the chalkboard for students and co-teachers as a reference and to share how a teaching artist organizes her dance journal notes (Jeannine Osayande, email message to Avalon Nemec, May 14, 2020).

17 In the dance movement “around the world,” the dancers balance on their bottom with feet raised a few inches above the ground. They use their hands to spin their body in place.

URLs

https://whyy.org/episodes/visions-of-community

Works Cited

Asante, Molefi Kete, and Kariamu Welsh Asante. 1990. African Culture: The Rhythms of Unity. Trenton, NJ: African World Press, Inc.

Baeten, Marlies and Mathea Simons. 2014. Student Teachers’ Team Teaching: Models, Effects and Conditions for Implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education. 41:92-110.

Brinkmann, Jodie and Travis Twiford. 2012. Voices from the Field: Skill Sets Needed for Effective Collaboration and Co-teaching. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation. 7.3:1-13.

Deafenbaugh, Linda. 2015. Folklife Education: A Warm Welcome Schools Extend to Communities. Journal of Folklore and Education. 2:76-83, https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Deafenbaugh.pdf.

Friend, Marilyn and Lynne Cook. 2016. Interactions: Collaboration Skills for School Professionals, 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Gay, Geneva. 2018. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Günay, Oya. 2016. Teachers and the Foundations of Intercultural Interaction. International Review of Education. 62.4:407-21.

Keele Manifesto for Decolonizing the Curriculum. 2018. Keele University. Accessed May 14, 2020, https://www.keele.ac.uk/equalitydiversity/equalityawards/raceequalitycharter/keeledecolonisingthecurriculumnetwork/#keele-manifesto-for-decolonising-the-curriculum

Kerin, Marita and Collette Murphy. 2015. Exploring the Impact of Coteaching on Pre-service Music Teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. 43.4:309-23.

Korankye, Charles. 2017. Adinkra Alphabet: The Adinkra Symbols as Alphabets & Their Hidden Meanings, 3rd ed. U.S.: Self-published.

Mabingo, Alfdaniels. 2018. Teaching African Dances as Civic Engagement. Journal of Dance Education. 18.3:103-11.

Patrik, Lela. 2005. Dancing for Cultural Sensitivity: The Elements of African Culture in Dance Traditions that Lay the Framework for a Community of Acceptance. In Dances of Our Ancestors: Honor, Memory and Celebration, ed. Indira Etwaroo. U.S.: Self-published, 100-15.

Ploessl, Donna, Marcia L. Rock, Naomi Schoenfeld, and Brooke Blanks. 2010. On the Same Page: Practical Techniques to Enhance Co-teaching Interactions. Intervention in School and Clinic. 45.3:158-68.

Pratt, Sharon. 2014. Achieving Symbiosis: Working Through Challenges Found in Co-Teaching to Achieve Effective Co-teaching Relationships. Teaching and Teacher Education. 41:1-12.

Richards, Judith. 1996. Forming the Habit of Seeing for Ourselves, Hearing for Ourselves and Thinking for Ourselves. In Teaching Malcolm X, ed. Theresa Perry. New York: Routledge, 39-49.

Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Visions of Community (Movers and Makers). 2020. Video. WHYY, 26:15, June 25, https://whyy.org/episodes/visions-of-community.