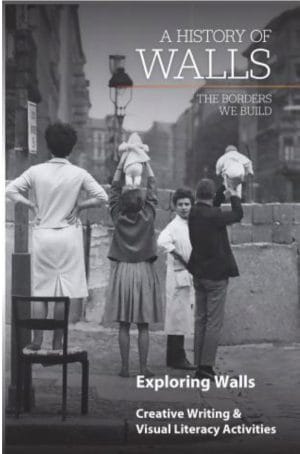

Image of Berlin Wall, courtesy Overland Exhibits. Learn more at https://statemuseum.arizona.edu/education/education-materials/exploring-walls

We live 65 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border and the Wall looms large in our psyche. But the U.S. wall is not the lone border wall; walls to separate and contain, protect and imperil, have been built in many different geographies and eras across world history. Facts about their construction and financial, human, and environmental costs are plentiful, but deeper understanding and empathy come when you join these facts with expressive works that reflect lived experiences.

In early March 2019, the Arizona State Museum mounted a traveling exhibition, A History of Walls: The Borders We Build, and received funding from Arizona Humanities to develop related programing. With the Covid-19 pandemic, ASM closed. Few people could see the exhibition, and programming had to be reconsidered. Lectures easily transferred to Zoom, but an interactive family program that generated and presented youth voices about the border was more challenging to transfer. Lisa Falk, ASM’s head of community engagement, reached out to all the program collaborators. Marge Pellegrino, award-winning teaching artist and author of Neon Words, jumped at the opportunity to join Lisa in thinking creatively about how to engage youth virtually with the exhibit.

With grant funding already extended and due to end in April 2021, we rolled up our sleeves and developed a writing and visual literacy workshop series for high school students. As we worked, we endeavored to:

- build an experience that invites students to think about big political actions and physical structures imposed by government authorities;

- have students go beyond articles, history books, and statistics when researching;

- encourage students to delve into peoples’ stories to better understand the impact of walls on communities and individuals;

- inspire students to link these stories to their lives and communities, sort out their mixed-up feelings, and express their understandings and emotions about politically constructed and metaphorical walls in a compelling format.

Using ASM’s K-12 email list, we recruited three high school teachers interested in using the theme of walls as a springboard for creative writing in their digital classrooms. Funding for teacher honoraria and timing limited this opportunity to three classrooms. Teachers committed to:

- a six-session interactive Zoom workshop in early 2021

- participating with their students for each 75–90 minute session

- facilitating sessions for student research

- providing the Zoom classroom, using Padlet, and saving the Chat entries

- securing permission for recording and sharing the collaborative poem

Grant funding allowed ASM to provide honoraria to Marge for co-developing the curriculum and co-facilitating the workshops. It also provided honoraria to the teachers, acknowledging their participation as important. One teacher used her honorarium to print a chapbook of her students’ writings.

Workshop Intentions

Intentions for students

- Learn about and compare the history of four border walls (China, Berlin, Israel-Palestine, and U.S.-Mexico) from multiple perspectives

- Explore the complexity of people’s relationships with walls

- Discover research resources and creative responses to border walls

- Gain skills in visual literacy to promote deeper seeing and analysis

- Use creative writing tools to build writing skills, including collaborative approaches

- Create and facilitate group presentations in a virtual environment

Intentions for teachers

- Experience interactive creative writing and visual literacy through virtual processes

- Understand that creative writing benefits from the use of a variety of prompts to build a final piece

- Experience how research feeds students’ creative writing

Methodology

Both Lisa and Marge have experience engaging young people in various writing activities that connect them to museum objects, place, identity, and action. Marge has observed the magic of the writing process in building resilience and confidence in youth. As we developed the curriculum, we applied the successful visual literacy and writing tools that we knew could prompt student excitement in exploring and expressing their thoughts on this complex topic. Ultimately, we hoped they would realize that their ideas, emotions, and words matter. We also wanted to create a conduit for their voices to be heard. Reflecting on the research done by James Pennenbaker that documents how creative writing supports individuals’ physiological, emotional, and academic lives, we were excited by the potential of our multidisciplinary curriculum (2014).

In developing a methodology that would support a safe space, we considered students’ age, Zoom delivery, and the nature of the material. For some students the border wall is an internal part of their being, defining who they are and challenging them and their families almost daily. For others it was just an abstraction without an intimate connection. Realizing that this topic could be traumatizing, we had to devise safe ways to encourage participation. At one classroom teacher’s suggestion, some students submitted their comments through her and she entered them into the Chat anonymously. Everyone’s thoughts were valuable to the process. Everyone could contribute without risk. Although sharing was optional, we reminded participants that their ideas hold the power to inspire others and highly encouraged sharing. Throughout we let them know when what they said caused us to add something to our list or helped us remember a detail. All their sharing was met with gratitude.

We opened each session with an individual online search to find a quote about the session theme, such as creative writing, walls, listening, writer’s voice, or collaboration. The intention was threefold: activate students immediately, set an inclusive tone, and foster thinking about the theme. Researching and offering a quote allowed students to contribute easily, safely, and productively to the conversation. Reading quotes aloud focused and inspired us as we moved into the heart of that session.

The content and different perspectives offered during our work screamed for time to begin processing before we hit the Leave Meeting button at the end of class. A quick reflection that we asked was, “Today I am thinking about…,” which elicited:

Different perspectives and emotions people have on walls

How different each of the walls we learned about are

How walls were built for a reason, positive or negative

How there’s more to walls then what we see

Why the wall started to be patrolled more

How I felt the emotion rush through me

The extremities of separation mentally and physically by walls

Teacher responses to prompts validated students’ efforts, provided a different point of view, and offered a reframing that students could trust. For example, in one session a teacher responded to a prompt with, “I have faith that tomorrow the world will be better in your capable hands.”

Workshop Sessions

Pre-Session: Introducing Creative Writing

We offered an introductory 15-minute session to excite students about the power of writing. Marge explained how writing is her superpower: It helps her to process, build her understanding, problem solve, center, and have fun. Lisa introduced the walls topic for our writing explorations and the Arizona State Museum. We introduced writing tools like lists and rapid writing along with the notion that students would be the boss of how they responded. Mimicking how we would run the workshop sessions, students used the Zoom Chat to share their expressive superpowers and experience how their thoughts would be received. They met us and heard our enthusiasm, setting a positive tone for subsequent sessions.

Session 1: Introducing Walls through Visual Literacy

To make students comfortable with the subject and to create a foundation based on what they already know, we posed the positioning question: What comes to mind when you hear the word “wall”? Most students responded by looking at personal walls or the function of walls.

Walls keep my family and me safe from the chaos our world has started. They also are obstacles in my life, they keep me in, they keep me from exploring.

I think of something you can hang out on, lean on, cry on, or just think.

A defending mechanism where we tend to “wall up” our emotions with certain interactions with others.

I think about something holding me back. I also think about it as memories whether I put stuff up or take stuff down. I think of an obstacle that is unbearably difficult to overcome, but not impossible.

What comes to mind is loneliness: a disconnection, an empty, colorless feeling that sneaks its way in you–especially when it’s a wall that is put up between you and someone else you care for.

Barriers are like a stop to what you want to reach for or accomplish and they stop you from achieving your goal.

Walls most times separate things or people. Walls are what keep us from truly knowing oneself.

Students shared their ideas by posting them on a Padlet. Padlet entries are like Post-it Notes. In this way they could see what had bubbled up across the class. Simply by reading each comment aloud, we validated their ideas. Many comments pointed to metaphorical walls—walls we build around ourselves for protection, or barriers that confine and cut off people from those they love. This led to reflections on the impact of political border walls on the people who live with their consequences.

With this start of our study of walls and validation of ideas, we introduced the four border walls we would examine in the workshop: The Great Wall of China, Berlin Wall, Israel-Palestine barrier wall, and the U.S.-Mexico border wall.

We presented a PowerPoint overview of the introduction to A History of Walls as a poem. Stanzas started with “History loves a wall” and provided examples of how walls serve as a “demarcation of the ending of one thing and the beginning of another.” We introduced the line, “But for the people who live with these walls, the relationship is more complicated,” and used it as a refrain between contrasting viewpoints. The introduction ended with Josh Begley’s idea that “Borders begin as fictions.…But the stories borders tell—about those who reinforce them, protect them, subvert them, try to cross them, live in their shadow—are real.…Borders…are performed. They are lines drawn in the sand, spaces that bend and break and make exceptions for certain kinds of bodies” (2016). Uncovering those stories drove students’ research over the next sessions.

The idea of borders being “fiction” that is “performed” introduced walls as places for expression, or as Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano stated, “The walls are the publishers of the poor.” We showed images of murals interpreting borders in the U.S. and Ireland and of cross-border crop art of fish skewered, or swimming unimpeded, over the border demarcation between Poland and Ukraine. Then we used techniques from the Harvard Project Zero Thinking Routines Toolbox to facilitate students’ reading of two photographs. These strategies help students look closely for details, which are often missed because of the assault of visual stimuli in our lives. This method helps students hone visual literacy skills.

The first photograph documented a corrugated metal wall splitting a vast desert landscape with a U.S. Border Patrol vehicle on one side and a small community on the other. Students listed five specific details they saw (not analyzing, but rather naming actual things) and posted them in the Chat so others could see what everyone noticed. We repeated this exercise several times with the same image, helping them to build their observation skills. They also listed what thoughts and wonderings the image evoked. We facilitated the same routine with a second image. This photograph showed a metal sculpture adhered to a portion of the U.S.-Mexico border wall depicting migrants carrying objects and painted with symbols representing where migrants journey from, what they endure, and hopes they bring with them. Finally, we pushed students’ analyses, asking them to consider the two photos as one and write a title for this combination. Examples included:

Same Obstacles, Different Meanings

Seeing What You Want to See

Different Sides of the Same Story

We finished the session by returning to their own experiences. Students divided a piece of paper into three columns. In the first they listed the walls in their lives. In the second they shared how the walls serve them. And in the third they described how they interact with them. A student reflection that first bubbled up here, and was echoed by many students in the remaining sessions, was:

The walls in my life are the ones who protect me and the obstacles that I run into. The purpose of a wall is to keep you inside of its barrier. We go through walls, we jump over walls, and we break them down.

Session 2: Introducing Sources

Session 2 introduced the role of research in creative writing. Students were divided into groups to research the four walls. They began by using the online A History of Walls exhibition script focusing on the panel text, photos, and maps for each wall. To create student-directed questions, we brainstormed questions based on what they thought was important to know about border walls and questions they wanted to hold in mind as they conducted research.

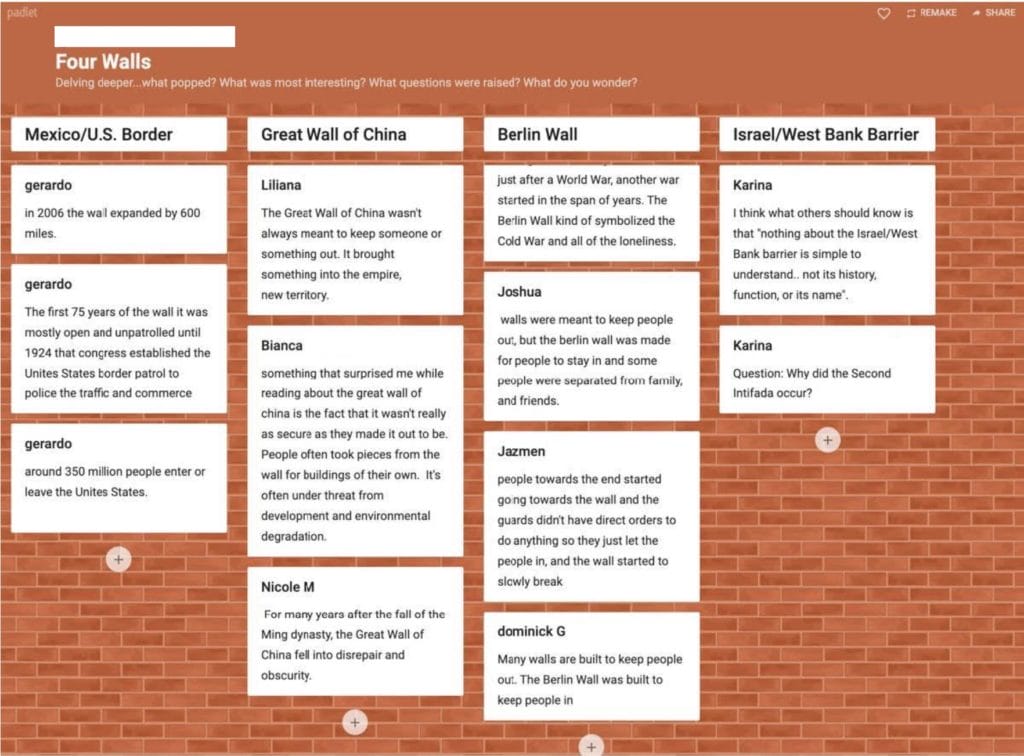

After 15 minutes of initial research, we reconvened. Using Padlet, we asked students to share what popped in their research, what resonated or surprised them, and what new questions research evoked. By organizing the Padlet by each wall, students saw what others in their group found interesting and made cross-wall comparisons. The ensuing discussion set up additional questions to investigate when conducting the next round of deeper research.

Image courtesy Lisa Falk and Marge Pellegrino.

To get beyond “facts,” we introduced the concept of being a museum curator who is responsible for finding materials to tell a story that will incite a connection with viewers. Exhibits often include objects, photographs, documents, maps, artworks, videos, oral histories, soundscapes, songs, quotes, and poetry to tell their story.

To illustrate how different modalities can evoke emotion and bring the viewer/listener into the story, we showed them the work of two artists—Alejandro Santiago in Mexico and Alvaro Enciso in the U.S. Borderlands.

We intended student “exhibits” to be a creative gestalt about the meaning of their assigned walls. The only parameters were that they be short and lean toward creative nonfiction: more like a poem or dance with the truth they found rather than a litany of facts. They were charged with making us care. Their research presentations would give them additional details and understandings to layer with their personal feelings in subsequent creative writing work, which would lead to writing a collaborative poem in the last session.

Upon returning to his village in Mexico from a fellowship in Europe, sculptor Alejandro Santiago felt like he entered a ghost town. In response to the emptiness created by the migration of the village’s youth, Alejandro created 2,501 life-sized clay figures to represent the 2,501 community members who had left. The video excerpt we shared about his project made visceral the magnitude of that loss and a desire to know the journey stories the people represented.

Alvaro Enciso’s art reflects the tragedy and broken dreams that he sees weekly while hiking remote desert migrant trails with the humanitarian group Tucson Samaritans to leave water to prevent migrant deaths. We showed pictures of his work Donde mueren los sueños (Where Dreams Die), a project that uses “secular” crosses to mark locations where migrant remains have been recovered. He explains, “I have planted nearly 1,000 crosses to bring attention to the more than 3,000 people that have died in southern Arizona while crossing the desert to find their place in the U.S., to find their piece of the ‘American dream’” (Donde mueren los sueños Artist Statement, provided by Alvaro Enciso, 5/24/21).

Session 3: Researching and Creating Presentations

Session 3 was devoted to students’ research on their own and during class time facilitated by their teachers. We provided weblinks for a variety of resources to start their exploration. Each student contributed slides highlighting their findings about their assigned wall for their group presentations at our next meeting.

See the Classroom Connections link in the sidebar to access the weblink resource page we developed for students.

Session 4: Sharing Discoveries and Listening with Intention

Before starting group presentations, we brainstormed strategies for active listening so students would engage and think critically about the information their peers presented (instead of zoning out in the comfort of their bedrooms). The artifacts the students shared included video clips, songs, poetry, images of mural art, and stories. These gave insights into the feelings of the people affected and illustrated creative resistance and accommodation to a wall imposed on them. Information that most resonated with students from the presentations included:

A story of ingenuity that drew on the Trojan horse legend. In East Berlin, some clever builders created a hollow space covered with the hide of a cow. The first few riders escaped to the West, but after someone tipped the border guards, a young woman trying to unite with her boyfriend was caught and the cow became legend.

A Palestinian poem expressed the limitations and complex emotions the Israel-Palestine wall caused the writer and his family.

A legend about the Great Wall of China pointed to the sacrifice by citizens enslaved to build it. A widow’s wailing cries were so loud a section of the wall crumbled, revealing her husband’s remains.

People’s opposition to government positions in images of mural art depicted people driving through, jumping over, or peeling back border walls.

Entrepreneurship was discussed in a story of a family business ferrying people across the Rio Grande, which the student group juxtaposed with number of river drownings by those without access to such a way to cross.

Students intermingled facts with these stories and the emotive pieces, which allowed some students to feel comfortable later sharing their stories of being separated from family by the U.S.-Mexico wall. Their presentations beautifully illustrated a statement by artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, “Now more than ever, when the nationalisms come in, is when art is required—is required to establish dialogue, to ask questions, to bring people together” (2021). The feelings and wondering that bubbled up included:

Uncertainty and doubt. Both for the implications that any piece of land can be crudely split and that over history that is exactly what has and is what happens.

It doesn’t matter what the walls affect, they go up either way even when the public is opposed.

The Berlin wall was to keep people in. Other walls are to keep people out.

Why are countries even divided in the first place?

The images and videos opened my eyes to the struggles people of this world go through and also made me question how important these walls are that destroy humanity.

Walls can’t make you feel safe, they can make you very uncomfortable.

Session 5: Finding Voice

To reinforce shared information that was most successful in connecting with an audience, we asked students to consider what stuck with them from the presentations. Marge knew from past teaching experiences that students are more likely to incorporate what they recognize as effective into their own process when they identify what pops in other people’s work. Overwhelmingly what stayed with them were strong details, stories, art, poems, and details that were unusual or showed a shift in thinking.

From thinking about strong writing, we moved to voice. We asked students to compose a short line of dialogue from six points of view. They wrote what a wall might say, a wall builder, a wall crasher, an activist, someone or something affected by a wall, and what students would say to the wall.

Choosing the most powerful voice from that writing, they expanded and extended it on the page. They chose any vehicle that best amplified the voice: a letter, conversation, poem, descriptive paragraph, or song lyrics. Sharing via a Padlet, we heard what different voices had to say and observed how different each take on a particular point of view could be:

Impacted by the Wall

My roots have been cut, crushed under the weight of thousands of pounds of concrete. The sun only shines above my head, not on my sides as I’m stuck in between two lands. I will not survive.

Wall Crasher

As I stand there staring at this wall thinking about my plan to break it down, I hear a deep melancholic voice ask, “Do you hate me that much that you want me gone?” I was startled and asked, “Who is there?” The voice erupted again, “I didn’t choose to be here. I didn’t want to divide.” Knowing now it was the wall that was speaking, I answered, “Now I’m going to tear you down so we can cross over and rejoin our family.” Then it was silent.

Wall

sorry for the inconvenience i have made

sorry that i bound you here

it’s my nature as i’m a wall

Wall

I may just be a wall and people love and hate me, but I protect them and I shelter them. I hear everything that goes on within my walls, I hear their laughter, their cries, and I protect them from the outside world.

Wall

People don’t really know what walls are really used for, I was made to support roofs and floors, and people use me to trap people, inside or out, and I’m the bad guy?

Wall Activist

I see the wall’s intentions and I’ve decided I’m going to speak out against it. This slab of concrete is cutting through the natural world, our beloved earth’s beauty, all for some petty human turmoil. It’s not right. It doesn’t feel right.

Student

Dear world, it’s me. Why build walls? Is it only to separate, or is it to build your reputation? Even then, why separate? Why break apart families and friends, and why separate lands instead of sharing? If it is to build your reputation, why not leave the world open to the many wonders that all people share? That’ll surely let everyone know your name. Right now, it seems like you want to separate, with all the evil leaders in power to uphold that separation, but just imagine how lovely and wonderful it would be, if we could all rejoice again and see our loved ones, once again.

We asked students to think about feelings that came up as they wrote, listened, and read what others had to say. A sampling of those emotions included sorrow, anger, blame, loss, sadness, determination, and surprise. Since we looked for the power in different voices, the culminating writing activity asked them to look for the power in the session and to finish the lines “Today….and Tomorrow….”

Today I will hold my ma a bit tighter.

Today the voices moved me.

Today I felt sad. Tomorrow I will look for hope.

Today I will help my community. Tomorrow I will share the love with my family.

Today I saw the different perspectives and emotions people have on walls.

Today I will smile.

Session 6: Power of Collaborative Art

In a visualization activity, we asked students to consider how a wall might transform from a barrier, keeping people apart, to a means of bringing people together. We asked them to close their eyes and visualize: What might it look like? Who is involved? What is involved? What does it sound like? What does it feel like? After opening their eyes, students via Chat shared a word or phrase that captured their ideas. We used this to introduce a series of photographs and videos of artists and activists whose work engages with border walls with the intention of creating dialogue. As an entrance to these projects, we discussed Tanya Aguiñiga’s quote, “I started thinking more and more about taking back the fence and changing it from being a place of pain and trauma into a generative place that we can reclaim” (2021). We asked students to pay attention to what popped and what feelings bubbled up as they observed the ways these people transformed walls in the following examples:

Messages on colorfully painted metal columns of a section of the U.S.-Mexico border wall expressing blessing, hopes, positive hugs, encouragement, and intentions: Dios Sabe, Hay Sueños, Amor, Love, Vive Hoy

A U.S. Border Patrol agent looking up at a larger-than-life photographic cutout of a Mexican baby staring down over the wall

Berlin wall images including a cartoon of someone jumping over the wall and another of a car crashing through the concrete

Two street art images on the Israel/Palestine wall: one a realistic poster-like image of a woman’s innocent face captioned “I am not a terrorist” and the other imagea similar-looking woman holding a military-style weapon captioned “Don’t forget the struggle”

A cross-border bilingual choir singing “With a Little Help from My Friends”

A soundscape by Glenn Weyant using the border fence as a musical instrument, playing its metal columns with a bow and mallet

A performance art piece, Obstruction, by Kimi Eisele that highlighted how the wall obstructs animals

The example that resonated most was R. Real’s performance art, Teetertotter. Watching children and adults playing on a seesaw rising and falling on alternating sides of the border, and hearing their laughter, projected a sense of happiness created by their shared togetherness. After discussing the examples, Lozano-Hemmer’s insistence that “art is required to establish dialogue, to ask questions, to bring people together” became our call to action.

Students began work on a collaborative poem to capture what they believe is essential for others to know about border walls. We asked them to do a quick-write enumerating what they felt are the most important, specific things others need to understand about walls and barriers. From this, each student donated one line. Working together, we moved the lines, sharing our strategies and thinking as we grouped or separated lines until we found an order and structure that created a strong poem. Students audio recorded the final poem.

Conclusion: Our Voices Are Strong and Heard

One strength of this exploration was working from the foundation of the A History of Walls exhibition, which considered walls in diverse times and geographies. The exhibition, our additional materials, and artifacts from students’ research uncovered how these four sites held stories that echoed across time and place. Students experienced these time capsules in a very specific here-and-now, while the pandemic and the shutdown served as a barrier that both protected and divided us. During this epic era, we looked broadly at the past, seeking other times and places that might hold truths that we can use to reflect on our regional border wall situation as well as our metaphorical walls. The workshops met our intentions in ways that went deeper than what we anticipated.

Throughout we touched back to students’ emotional reactions. What are you feeling about this? What do you do with those feelings of empathy, emotion, and anger that surfaced? Some students reflected on their situations and growth. They found that research will support deeper understanding and can apply to more than a term paper. They discovered that border walls are not either/or; there is a complexity to understanding the value and the destructiveness of walls. They felt their own and saw others’ reactions to different understandings of walls. They saw that art could invite different perspectives and open pathways to reach over borders for connection. They hoped that writing and sharing a poem might change someone’s feelings. Many students felt more inclined to talk with family or friends about how the U.S.-Mexico border affected them, their families, and community. A few were inspired to get involved in border issues.

Students were exposed to a process, a blueprint of an approach they could use to seek a broader understanding of any complex issue they encounter. For us as educators, the most gratifying outcome was that students felt the workshop was meaningful, they were safe to express themselves, and they were heard.

You made me open up my creative mind and question, wonder, and research about the Great Wall of China. I’ve learned things I would never have known. I now have a different perspective on walls. Thank you for making me wonder. –Liliana

I felt welcomed. I felt seen. I felt comfortable. I felt all the things I was expecting not to. … [It was] an experience that has struck me in the most unexpected way and has changed me. You opened my eyes to a world I do not want to forget about anytime soon. A world of transforming old pain into new beauty, new hope, and tearing down walls of all kinds that will cross my path–starting with the one in my heart (and the one dividing our people in México from us). –Karina

Along the whole program, I felt like I was a part of something, meanwhile I was learning all this new information which I could then talk about in new ways and techniques. A part of my family was affected by borders and it hit close to my Heart. –Hector

Thank you so much for everything that was provided from knowledge to even a safe environment where each view got to be shared without criticism. –Gerardo

The workshop led students to feel the importance of human stories in fostering understanding, and it empowered their voices, as heard in these excerpted lines from the collaborative poems:

Walls are more gray than black and white.

If you are angry at the wall, be angry.

We build walls around ourselves to block out the people around us

Meaning will change… (Barrier and a place of sorrow became a place of pride)

Walls separate us and keep many secrets,

instead of looking straight at the wall, look around it.

Walls never work forever.

The barrier that we create in our hearts

must be broken

to heal and grow

So although these walls may rob,

conquer,

and divide us all—they

cannot and will not

ever take our voice.

Recordings of the poems from the three classes are on ASM’s website along with related writing and visual literacy activities and the two radio interviews.

Lisa Falk has nearly 40 years of experience in developing, producing, and evaluating informal learning programs. As Head of Community Engagement at Arizona State Museum (University of Arizona), she is responsible for the museum’s exhibits, educational programs, and outreach efforts. She wrote Cultural Reporter and Bermuda Connections: A Cultural Resource Guide for Classrooms, both awarded honorable mentions by the American Folklore Society, and serves on the Journal of Folklore and Education Editorial Board. In 2012, Falk’s work received the Museum Association of Arizona’s Award for Contribution in honor of her museum-community collaborative work.

Teaching artist Marge Pellegrino works with diverse audiences and leads writing and art adventures in community, library, school, and agency settings. She has conducted residencies and staff trainings in rural and urban communities. For 20 years, she facilitated programing for the Owl & Panther project, which serves refugee families. Her innovative Word Journeys program had a 12-year run at Pima County Public Library and won a White House Coming Up Taller Award for excellence in afterschool programing. Her recent teen book Neon Words: 10 Brilliant Ways to Light Up Your Writing (Magination Press, 2019) inspires others to express themselves on the page.

Works Cited

Pennebaker, James W. and John F. Evans. 2014. Expressive Writing: Words That Heal. Enumclaw WA: Idyll Arbor Press.

Begley, Josh. 2016. A History of Walls Introductory Panel. Overland Exhibits. Accessed July 13, 2021, https://walls.overlandexhibits.com/intro.

Art21, 2020. Season 10, Episode 3, “Borderlands.“ Aired 10/02/2020, https://allarts.org/programs/art21/borderlands-4m0kef/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=012021.