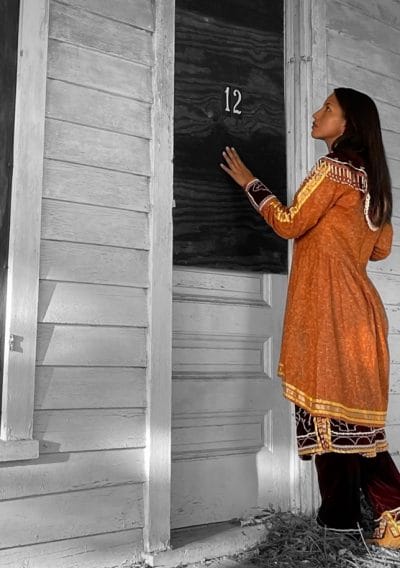

Door of the lower mission house of Thomas Indian School, Seneca-Cattaraugus Territory. Photo by Hayden Haynes with Jocelyn Jones. © 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones.

This exhibition,

“It’s about community,

told by community, and

supported by community.”—Hayden Haynes

This photo essay by Hayden Haynes is part of the culmination of a community looking at the effects and aftereffects of one Indian Boarding School. This is not to say that this community has reached a conclusion on this matter, but it is a start. To be honest, many Native Nations, communities, and families are just beginning to come to terms with the traumatic events that surround this particular past.

Acknowledging uncomfortable histories is a position that all peoples must take to come together, discuss, and heal. Reminders will be centered on what is uncovered on former school lands over the next few years. The talking points will revolve around murdered, missing, lost, assimilated, and tormented young people, and the families’ pain surrounding their disappearance. For the survivors, we will find many, but not all. With this in mind, we must come together and resolve never to allow this to happen again to anyone.

Boarding schools arrived at the onset of U.S. government Indian assimilation policies from the 18th century to the mid-20th century. Americans assumed Indigenous Peoples would disappear in a matter of time and ramped up the process with Institutionalized Boarding Schools to assimilate Indigenous youth before they were fully enculturated with their families’ languages and cultures. Boarding School policies certainly embraced Richard H. Pratt’s ideology of kill the Indian, save the man (1892).

The efforts of the curators and collaborators of an exhibition displayed at the Onöhsagwë:De’ Cultural Center on the Seneca Nation’s Allegany Territory tell part of the story of the Thomas Indian School (TIS) in Irving, NY. It is titled Hënödeyësdahgwa’geh wa’öki’jö’ ögwahsä’s. Onëh I:’ jögwadögwea:je’. We Were at the School. We Were There. We Remember. The exhibition had two additional showings and will continue moving to keep deepening awareness of these unsolved losses. An essay outlining the history of TIS follows this section about the exhibit.

The Onöhsagwë:De’ Cultural Center has been honored to host the exhibition. The story came together in a quick but deliberate curation of artifacts of TIS’s history, family stories, Seneca Nation’s Archives, contemporary photographs, and art made specifically for the exhibition. Although the Center had limited roles in this endeavor, the power of the exhibition lies in how Haudenosaunee People from all over Western New York offered their expertise, mementos, or newly created pieces to ensure this exhibition came to fruition. The building of the exhibition simultaneously brought awareness and education, but most importantly the acts of creation and display are a healing for all of us.

The truth is that if you are an Indigenous Person on Turtle Island, then you probably have some connection to this story. As a result of knowing all of this, you are also aware that we are not supposed to be telling this story. We were supposed to become them. That did not happen. We are still here. We invite institutions to reach out to Hayden Haynes to bring this powerful, ongoing story to your communities. Through educational sovereignty and the sharing of exhibitions that illustrate the histories that we need to tell about our places, we hope to make sure no one has to create another exhibition like this one again.

by Joe Stahlman

Director, Onöhsagwë:De’ Cultural Center

Works Cited

Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction. 1892, 46–59. Reprinted in Richard H. Pratt, The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites, Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” 1880–1900. 1973. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 260–71, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4929.

When people think of sovereignty they think about political sovereignty, but most do not consider the freedom to choose how they wish to educate their children. The history of the Thomas Indian School (TIS) still reverberates through our communities. Its effects manifest in many different ways for individuals and for our community as a whole.

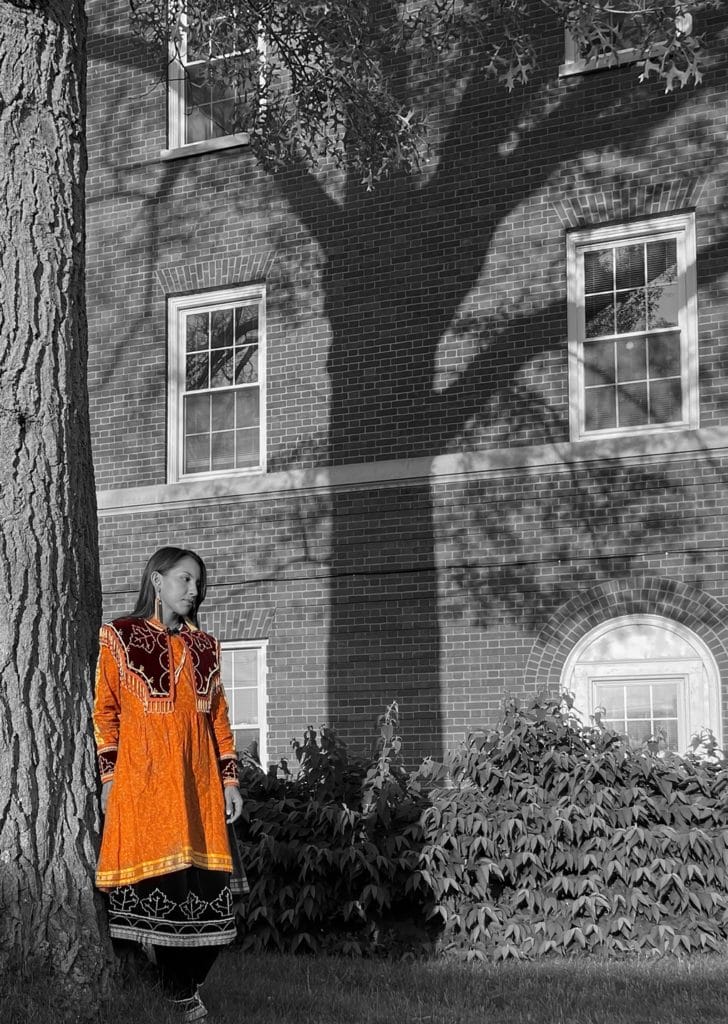

In 2021, I made a pair of antler comb earrings in memory of the children who went to TIS. This evolved into a social media photography project to build more awareness about the “school.” I asked Jocelyn Jones, a fellow Cattaraugus-Seneca and culture bearer, if she would model in traditional regalia for the photos, and she agreed. Jocelyn owned an orange ribbon dress, which she wore for the photographs. The orange color is associated with the “Every Child Matters” movement, which aims for truth and reconciliation regarding Native American Residential Schools*. This work serves to show the strength and fortitude of our peoples, a reminder that we survived and have thriving communities today.

Jocelyn and I visited various sites on the Cattaraugus Territory related to the Thomas Indian School. These included the “lower” mission house, Wright Memorial Church, existing structures of TIS, and the United Missions Cemetery where missionary Asher Wright and his family are buried. During our stops Jocelyn and I talked about the sites. She explored the buildings and sites and reflected on the magnitude of it all. This series of photographs captures the realness of her emotions that day, and in some ways the emotions of many people in our communities today in relation to TIS.

Very quickly, the photos evolved into an exhibition, which was funded by the community and our Native allies. The exhibition expanded to include text, two-dimensional and three-dimensional art, video, and an installation piece. The original text was written solely by Haudenosaunee scholars. It is truly a community effort, and a story that needs to be told through our voices. This exhibition is part of our healing, a statement of a history that is not fully told or acknowledged, and a call for advocacy on Indigenous sovereignty.

Nya:wëh

Hayden Haynes, Artist

Onödowa’ga:’ (Seneca) – Deer Clan

*Orange Shirt Day is recognized on September 30 in Canada and elsewhere. Find Teacher Resources developed by the First Nations Education Steering Committee and First Nations Schools Association in Canada in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada at

https://www.orangeshirtday.org/teacher-resources.html.

From the Editors: The Journal of Folklore and Education works to ensure that students can bring their whole cultural identities into the classroom. This is educational sovereignty. We honor Indigenous educators who bring their perspectives, languages, and traditional ways of knowing into learning spaces. We ask that teachers who are not Seneca realize the significance of this work and honor its specificity. Because we know one story, we do not know them all. Because we have one student, one family, or one cultural community willing to tell their story, we cannot ask them to stand in for listening to other stories. To learn more about the history of Indian Education in North America, here are some resources.

Chilocco Indian School: A Generational Story, (2022), set in present-day Oklahoma, was compiled from the experiences of real students who attended Chilocco, and their recollections were shared through oral history interviews, photographs, letters, and other archival sources. A Project Based Learning module is also available for educators.

Healing Voices Volume 1: A Primer on American Indian and Alaska Native Boarding Schools in the U.S. (2020) is designed for educators by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

The Iroquois Genealogy Society conserves the history of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ people’s documents and history through outreach, preservation, restoration, and research.

Selected Photos from the Exhibition

Hënödeyësdahgwa’geh wa’öki’jö’ ögwahsä’s. Onëh I:’ jögwadögwea:je’

We Were at the School. We Were There. We Remember.

by Hayden Haynes with Jocelyn Jones

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. One of the remaining brick buildings of TIS, the old Infirmary.

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. At the gravesite of Asher Wright and his wife Laura at the United Missions Cemetery.

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. At the gravesite of Asher Wright and his wife Laura at the United Missions Cemetery.

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. Wright Memorial Church in Bucktown—a neighborhood in Cattaraugus where Asher Wright practiced his Presbyterian services.

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. In front of the old Infirmary. Colored images on right side include various teddy bears, shoes, and other items community members left in remembrance of the children who attended Indian Boarding Schools. Historical photo below is shared courtesy of the authors.

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. One of the remaining brick buildings of TIS, the old Infirmary.

© 2021 Hayden Haynes and Jocelyn Jones. Picking an orange lily that grows wild in the United Missions Cemetery.