The Crystal Book, Book 1, cover art.

The Crystal Book (El Libro de Cristal) is a multilingual, transmedia comic developed as both a powerful story and an adaptable teaching tool. The project emerged from my doctoral dissertation, Hero Genesis and Crisis: Comic Books and Identity Formation in Revolutionary Cuba (2021), and took shape through collaboration with artists and writers in Cuba. While teaching in New York City, I began adapting these ideas into a classroom resource that could connect diverse students through storytelling, history, and cultural exploration. The result is a comic-based approach that uses visual storytelling to spark curiosity, support student inquiry, and connect culture with creative expression.

The story begins in a Brooklyn middle school, the very school where I was teaching while developing the comic. The characters and settings of the comic world were inspired by my students and colleagues. I built the fictional world to reflect their real one, so students could see themselves in the story and feel connected to it.

In the narrative, Karla, a Cuban American student and aspiring comic artist, submits her comic to a publisher for a competition. But when she arrives at the publisher’s office, he transforms into a monstrous tentacled figure, a cosmic force that feeds on forgotten and untold stories. The monster intends to consume Karla’s story and erase her memory of ever creating it. As it begins to erase her work, Karla enters a psychological crisis, feeling her voice slipping away. At that moment, a portal opens and pulls her into another world. There, she learns that this dark force is weakening the power of the crystal book, a mythical artifact that holds all stories ever told. By erasing cultural memory and silencing creative voices, the villain seeks to control people by controlling the stories they tell and believe. Karla must now protect these stories before they are lost.

To do so, she journeys through worlds inspired by pre-Columbian Mexico, colonial Cuba, and Golden Age Spain. Along the way, she meets cultural and mythological figures such as Quetzalcóatl, a deity of knowledge; Andrés Pedit, a spiritual guide who channels the Orishas; and Don Quijote, the visionary dreamer. These encounters help her realize that her personal story is connected to larger cultural narratives across time and place.

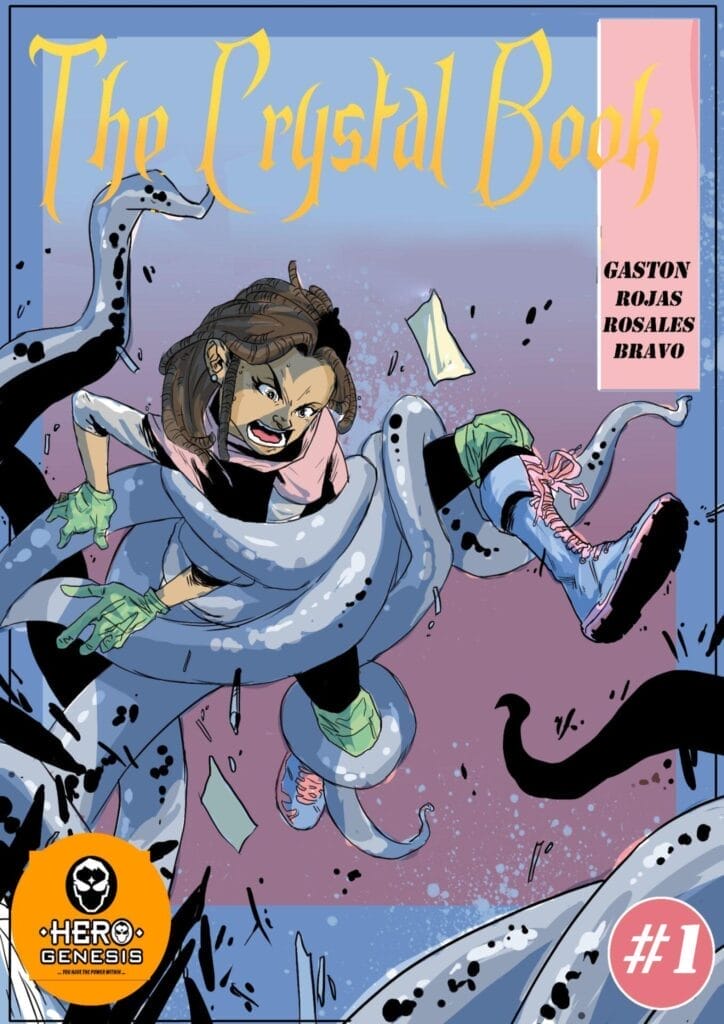

The Crystal Book, Book 1, pages 9 and 10.

The structure of the comic follows a project-based learning (PBL) model. Book 1 introduces the central question: What happens when stories are erased? Each following book acts as a case study, set in a different cultural context. As Karla explores each world, she gathers knowledge, meets cultural guides, overcomes challenges, and ultimately creates her own story. This mirrors the project-based learning arc, where students investigate real questions, build understanding, and express what they’ve learned through creative work.

To support this learning, I created versions of the comic in Spanish, English, and bilingual formats. I adjusted the amount and complexity of text for different language levels while maintaining the visual narrative consistency to support differentiation. This allowed all students to follow the same story and engage with the same images, while being challenged in ways appropriate to their language proficiency. This structure supported a translanguaging approach, as described by Ofelia García, where students use all their languages as tools for thinking, expressing, and creating. In practice, they might read in Spanish, discuss in English, and write in both, drawing on their full linguistic repertoire to make meaning.

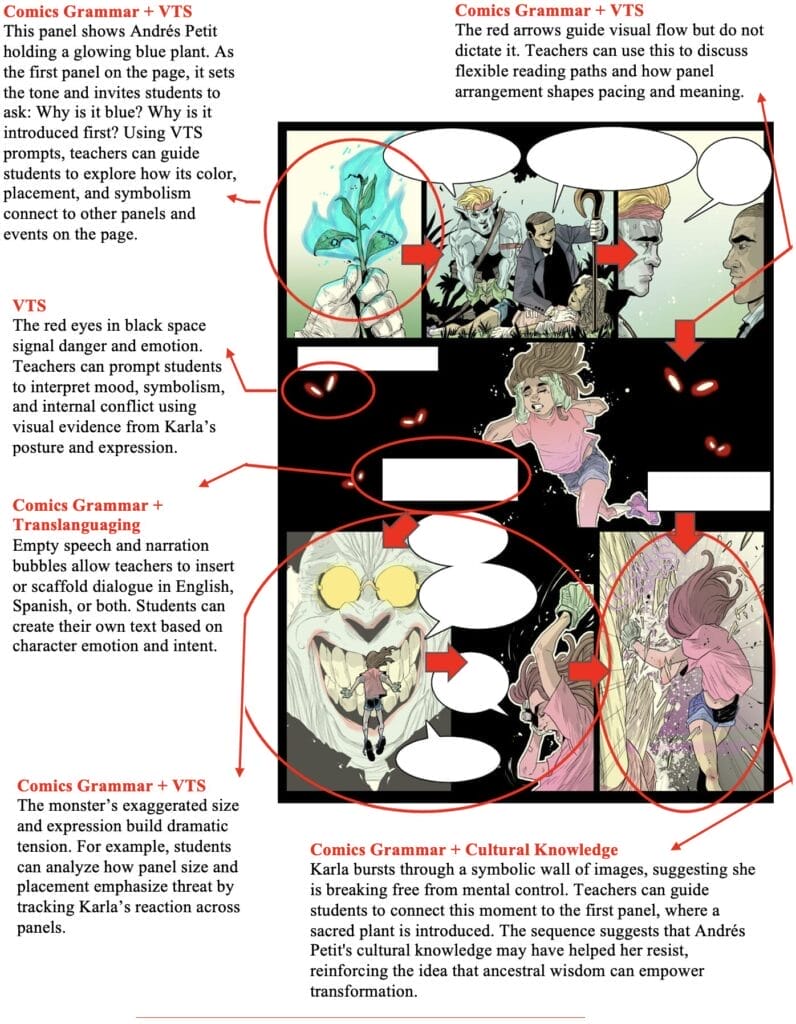

The comic format strengthens this approach by engaging students in visual storytelling. As Scott McCloud explains, comics operate through a distinct visual grammar—how panels are arranged, how time and motion are represented, and how images and words work together to create meaning (1993). In The Crystal Book, students learn to follow visual cues, interpret character emotions, recognize cultural symbols, and understand story flow across frames. This process builds multimodal literacy, helping students connect what they see with what they think and feel. Because the visual narrative remains consistent across all versions of the comic, it provides a shared foundation for all learners, regardless of language level. This consistent visual storytelling, paired with differentiated text, creates multiple entry points into the story and supports a wide range of learning needs.

To deepen interpretation and discussion, I integrated aesthetic development practices inspired by Abigail Housen (1999). I used strategies that kept students’ “eyes on the canvas”, asking them to describe what they saw, explain what made them say that, and build meaning through dialogue. This helped them move from personal reactions to more detailed, evidence-based observations. These habits—close looking, using language to support thinking, building shared understanding—strengthened their visual thinking and supported their growth as readers, writers, and critical thinkers.

The methodology embedded in the creation and structure of The Crystal Book empowers students to become both storytellers and critical thinkers. They learn to see their languages, cultures, and lived experiences not as obstacles, but as powerful tools for learning and expression. Just as Karla protects cultural memory by authoring her own story, students are challenged to do the same, crafting narratives that link their personal identities to broader histories and communities. As part of the project, students begin developing their own stories using the comic medium, applying the same visual and narrative tools they explore in the comic. Developed through cross-cultural collaboration, grounded in classroom practice, and shaped by student voices, The Crystal Book offers a flexible, creative model for comic-based learning, one that bridges language and culture through inquiry, imagination, and storytelling.

The Crystal Book, cover art for Books 2-5.

Javier Gastón-Greenberg is a Curriculum Designer at Educurious, powered by NCEE, where they develop project-based learning Social Studies curriculum for middle and high school. They hold a PhD in Hispanic Languages and Literature and have taught English and Spanish Language Arts in both secondary and higher education. As Co-Founder of Hero Genesis, they create empowerment programs that use comics and graphic novels to support literacy and critical thinking, collaborating with visual artists to design curriculum based on visual storytelling.

Works Cited

García, Ofelia., and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gastón-Greenberg, Javier. 2021. Hero Genesis and Crisis: Comic Books and Identity Formation in Revolutionary Cuba. Dissertation. Hispanic Language and Literature at Stony Brook University.

Housen, Abigail. 1999. Eye of the Beholder: Research, Theory and Practice. Visual Understanding in Education, https://vtshome.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/5Eye-of-the-Beholder.pdf

McCloud, Scott. 1993. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins.