For thousands of years tribal elders would sit down with the children and tell them stories. The stories were always the same, there was never a word out of place. It had to be that way, it had to be accurate.

Darren Parry, author of “History and Perspective” and former Chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation

“History and Perspective,” by Darren Parry in Tremonton, Utah.

All photos courtesy of the authors.

In this story collected and shared as part of the OurStoryBridge online short-form oral history project from the Tremonton City Library in Tremonton, Utah, Parry recalls learning Shoshone history and culture from stories that his grandmother, Mae Timbimboo, told him. Parry recounts his excitement in elementary school when he heard that Shoshone history would be an upcoming topic. But Parry’s delight turned to shock and concern when none of the stories his grandmother taught him, such as how the coyote stole fire or how the eagle became bald, were mentioned in his class. Instead, this rich heritage was narrowed down to the events of the Bear River Massacre, the largest mass murder of Native Americans by U.S. Army forces in the American West.

Growing up, Parry “always believed that historical events were an absolute that transpired over time and had one conclusion.” So he wondered why his grandmother’s stories, the ones passed between the Shoshone people for generations, had been left out of the classroom and kept from his peers. It was through his confusion that Parry came to recognize history’s reliance on perspective. Rather than being definitive, history falls prey to the loudest voice or so-called victor in the narrative, and the classroom became another place where the tactics of the U.S. military overwrote the vibrant and rich Indigenous history of the land and its peoples.

In just over three minutes, Parry’s captivating story encourages listeners to ask tough questions: Who gets to write history? Which voices are represented over those that are absent, even silenced? The conflicting realities Parry faced in his classroom are, of course, still present today as students and teachers navigate the hard histories of race, culture, identity, equity, access, and other formative topics of diversity. In fact, his story brushes up against the topic of archival silences frequently discussed in the field of Information Science. Archival silence, as defined by the Society of American Archivists, can best be understood as a gap, intentional or not, within the historic record that, because of its absence, can result in distortion or misrepresentation of the past. Parry’s classmates learned the events of January 29, 1863, from one perspective without being given the tools to consider the full scope of the circumstances, actors, and results to examine the history of that day properly. By not including Indigenous voices in the lesson, students without a personal connection to the Shoshone people gained no greater grasp of the Shoshone life and history in Utah than the events of the Bear River Massacre. The resulting historical perspective is forced, effectively leaving the larger historical lens that Parry himself represented to go unacknowledged.

Consider, then, how much greater the impact of this lesson would have been if, for example, the stories from Parry’s grandmother had been included. What depths of understanding, curiosity, respect, and inclusion could have been created for Parry and his classmates? The consideration of diverse perspectives from a variety of voices should be fundamental to the educational process. Being able to access multiple viewpoints through previously unheard primary source material can be of substantial educational value; such resources can help to unmute the silences in the documentary record. Using the OurStoryBridge methodology, which targets short-form, digital oral histories made freely accessible on any device, Parry’s story along with over 750 others to date have been collected and shared online (with more added regularly) and are available free to classrooms across the country in an effort to do just that.

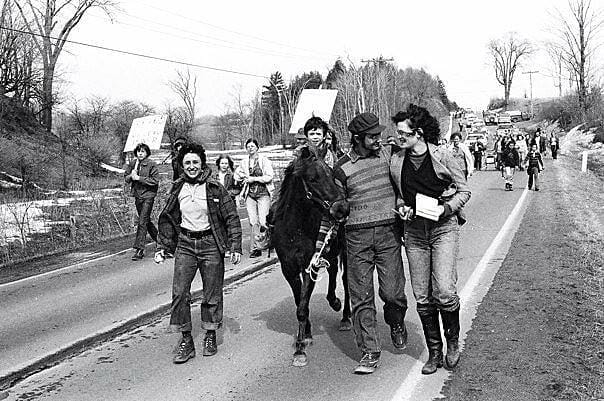

Ellen Rocco, “Young People Make Change,” in Freedom Story Project.

OurStoryBridge: Connecting the Past and the Present is a 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofit that supports crowdsourced community story projects emphasizing audio history collecting and sharing in three- to five-minute personal narratives with scrolling photographs. Founded in 2020 and incorporated in 2022, OurStoryBridge has the threefold mission to be a resource and toolkit for OurStoryBridge projects that preserve and circulate local audio stories past and present through accessible online media; to promote, build, and assist with the deployment of these resources in communities across geographic, cultural, socioeconomic, racial, and organizational strata; and to help strengthen these communities through sharing of their stories, including preserving the stories of older generations before they are lost and encouraging younger generations to become engaged community members. These tool kit resources are made freely available online to all those who are interested, as the vision of OurStoryBridge is to empower community members to cultivate connections across the generations, encourage civic engagement, celebrate diversity, and engender shared and durable kindness.

OurStoryBridge has supported the release of 22 story projects across 11 states in five languages, from Vermont to Alaska. When a new story project launches, the voices of each unique community present a healthy resource of primary audio and visual materials that enhance and enrich the community’s historical record—for community members themselves, for those beyond their borders, and in classrooms near and far. With stories provided and collected by community volunteers, this local participation yields and shares ample, representative voices. In line with the OurStoryBridge objective to encourage younger generations to become more engaged community members, we recommend Memria, an online audio collecting platform, to upload stories that can be embedded on each community’s individual website, making these stories easily accessible for general engagement online and for directed classroom use. For increased access, Memria provides shareable links; direct posting to social media; and free, downloadable audio streaming transcriptions of every story into 13 languages. Additionally, communities and individuals maintain the creative control to tell their own stories, thereby honoring the authenticity of their intimate voices and collective cultures.

To assist with bringing this multidisciplinary, multi-topic, and participatory archive into classrooms nationwide, OurStoryBridge created a free Teacher’s Guide. Now in its third online edition, kept up-to-date by volunteer educators and students, it catalogs all the stories collected and shared using the OurStoryBridge methodology. It grew out of a desire to connect educators to resources that capture student interest, inspire classroom discussion, enhance critical thinking, and provide structure and guidance for creating lesson plans using archival primary source material. Six documents comprise the Teacher’s Guide: How-To Guide, Sample School Assignments, School Story Project Protocol, Story Summaries, DEI Stories, and Story Selection Chart.

Tommy Biesemeyer, “Olympic Dream Fulfilled,” in Adirondack Community.

Each story in the guide features a synopsis, the story number, title, storyteller, and a hyperlink to the story. Associated tags in the Story Summaries and Story Selection Chart help educators find a narrative that suits the day’s lesson. These categories should not be viewed as rigid, given the relevance of all OurStoryBridge narratives for primary, secondary, and university classroom integration. For example, stories like Tommy Biesemeyer’s “Olympic Dream Fulfilled,” which documents the perspective of an Olympian ski racer’s successes, setbacks, and community, is tagged for the elementary level. But this story can also be broadly accessed across age groups and disciplines, including U.S. History, English Language Arts, and Sports Education.

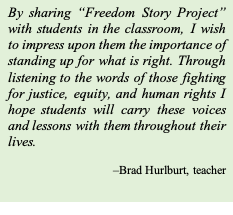

Brad Hurlburt, a Social Studies teacher for grades 9–12 at Keene Central School in Keene Valley, New York, notes the value of the Teacher’s Guide and the stories to spark classroom discussion: “Tommy Biesemeyer was one of our Keene Central School students. When we play [his story] in the classroom, the students learn about persistence, testing their athletic abilities, family support, and how even giants are human.” Biesemeyer’s short oral history recording demonstrates the power of stories to relay ideas not always easy to convey in conventional or textbook classroom lessons. Such first-person, primary source narratives presented through audiovisual content help build connections for students between classroom learning, their community, and real-world events past and present. They provide “valuable firsthand historical knowledge, including models of local civic engagement,” says Brad Hurlburt. This approach to sharing community-sourced stories in the classroom can lead to interdisciplinary discussions that expand students’ understanding and open up a more complex construction of history.

Breaking down the structure of the Teacher’s Guide demonstrates its useful properties for the classroom.

The How-To Guide defines OurStoryBridge and articulates the context for its use by answering the questions, Why should I use these stories in my classroom?and What do these stories add to current resources?

The Story Selection Chart and Story Summaries list every narrative collected by OurStoryBridge, organized by story project and sorted by categories and academic disciplines or teaching topics. Each story is presented by title, with a brief summary and hyperlink for quick access. Information in the Story Selection Chart is designed for middle- and high-school classes, while other learning levels, including university or elementary levels, can be easily found in Story Summaries. Educators can visit the Story Selection Chart to find narratives appropriate to many subject areas, including Social Studies, STEM, and English Language Arts. This same method applies for the Story Summaries section, which provides tags to locate a story and its hyperlink to click to listen.

The How-To Guide, Sample School Assignment, and School Story Projects Protocol walk educators through four methods for adding stories to their lessons—assign, present, suggest, and guide—giving details on using relevant stories to facilitate or add nuance to class discussions and offering suggestions for activities and homework that integrate the stories. OurStoryBridge encourages educators to play brief oral histories in the classroom as well as assign stories for homework and guide students toward specific stories that they can relate to upcoming activities or projects. One example is “Meeting John & Mary Brown, Abolitionists,” by Greg Artzner and Terry Leonino, better known as the musical duo Magpie. Together they recount teaching audiences about the lives of historic figures such as John Brown and Harriet Tubman through music and theater. This story can be included for discussion in classes relating to U.S. History, Music, Philosophy, and more. OurStoryBridge stories can also be used to present or introduce a topic, make a concept memorable, or stimulate further discussion. Two more examples among hundreds include “The Underground Railroad in the North Country,” by Jackie Madison, which details how the routes of the Underground Railroad in Upstate New York and Vermont have been used from the 19th century to the present, and “Lake Placid & the 1980 Olympics,” by Jim Rogers, which discusses the challenges of a small, rural town in the Adirondack Mountains hosting the 1980 Winter Olympics, the redemption it found in the “Miracle on Ice,” and the social and technological impact of televising the games.

Martin Tyler, “What Education Provided Me,” in Freedom Story Project.

At Paul Smith’s College and Clarkson University, university educator Bethany Garretson followed the Teacher’s Guide strategy of suggesting students use the primary source materials from OurStoryBridge story projects to amplify their research and writing in courses such as Adirondack History, Interpersonal Communications, and Environmental History and Social Justice. Throughout each semester, Garretson also invited available local storytellers to class meetings, further integrating these oral histories into her curricula and providing an additional layer of learning experience for her students and colleagues (some of whom adopted OurStoryBridge stories into their classrooms). All this highlights the mission of OurStoryBridge to strengthen community by creating closer bonds across generations and celebrating these newfound, shared, and informed connections.

Additionally, the Teacher’s Guide invites teachers to guide (mentor) students to tell their own stories with specific directions and scaffolding. This lesson in the Sample School Assignment section emphasizes learning the components of a good story as well as important soft skills such as proficiency in public speaking and fostering a sense of creativity. Within this type of lesson, students can recognize the value of storytelling, experience a story’s impact on both storytellers and their listeners, learn elements of a compelling story, practice constructing an outline to help tell a story, and develop public speaking abilities that promote confidence in sharing their voices and ideas. By the end of the assignment, students will have advanced their communication skills, which will be useful in their remaining school careers; professional development; and any area of communications, including structured organization, sequential thinking, and presentation skills.

Educators interested in having their students compose narratives may find it helpful if they first listen to a variety of stories using narratives from OurStoryBridge projects as a springboard for brainstorming. Students may find interest, for example, in the many narratives of culture and tradition from the Niraqutaq Qallermcinek “Bridge of Stories” in Igiugig, Alaska; of learning to love your local community from “Life in the Islands” from North Hero, Vermont; of finding inspiration in the great outdoors from The Adirondack Mountain Club’s “ADK Voices”; or through activism in the national issue-oriented “Freedom Story Project” sponsored by John Brown Lives!, which centers on themes of freedom and justice, human and civil rights, activism, and engagement. By focusing on creating story projects centered around communities or issue-oriented organizations, OurStoryBridge is positioned to gather many voices, perspectives, and lived experiences surrounding them

In addition to sharing primary sources, the Teacher’s Guide aims to impress upon students that they can create primary sources of knowledge and represent their moment in time by sharing their own histories and experiences through story. As a result, educators reinforce the importance of personal narratives, the impact that crafting an effective narrative can make, and thus the significance of their students’ individual and collective voices. The School Story Projects Protocol provides a rubric to encourage students to recognize that they, too, are storytellers and their lived experiences and perspectives can be valuable guides to others.

One student story comes from former Keene Central School student, Cal Page-Bryant, whose story “Citizenship” was shared as part of his school’s 12th-grade storytelling project in partnership with OurStoryBridge. Reflecting on the prompts—What do freedom and justice mean to you? How are they reflected in your daily life?—Page-Bryant tells listeners, “We are grown to uphold a legacy of human goodness and empathy, which has survived throughout history in spite of great setbacks through the work of people who do not bend from their conviction in a better world.” Page-Bryant describes the complicated intersection of freedom and justice in the present day and his fears surrounding living and acting in a world that is increasingly hostile, plagued by gun violence, disinformation, prejudices, and a diminishing sense of empathy. He asks how he and his fellow graduates can find a life of moral clarity and community. As he weaves the ways memory, meaning, and identity can conflict and cause division, he is able to find hope: “So in the midst of an uncertain world in which we are on the brink of citizenship, we have ourselves and we have each other. And with these two sources of support, we can accomplish great things in our lives for the human cause.”

One student story comes from former Keene Central School student, Cal Page-Bryant, whose story “Citizenship” was shared as part of his school’s 12th-grade storytelling project in partnership with OurStoryBridge. Reflecting on the prompts—What do freedom and justice mean to you? How are they reflected in your daily life?—Page-Bryant tells listeners, “We are grown to uphold a legacy of human goodness and empathy, which has survived throughout history in spite of great setbacks through the work of people who do not bend from their conviction in a better world.” Page-Bryant describes the complicated intersection of freedom and justice in the present day and his fears surrounding living and acting in a world that is increasingly hostile, plagued by gun violence, disinformation, prejudices, and a diminishing sense of empathy. He asks how he and his fellow graduates can find a life of moral clarity and community. As he weaves the ways memory, meaning, and identity can conflict and cause division, he is able to find hope: “So in the midst of an uncertain world in which we are on the brink of citizenship, we have ourselves and we have each other. And with these two sources of support, we can accomplish great things in our lives for the human cause.”

OurStoryBridge offers an avenue to explore the complex narratives of our nation’s communities, history, and people. Through efforts to hear and create a storyteller out of anyone with the desire to share their lived experiences, OurStoryBridge offers vital opportunities for education, civic engagement, and learning. Resources like the Teacher’s Guide provide easy-to-use, effective methods for deploying varied and insightful stories into classrooms and the minds of young learners, showing them that they, too, can produce important primary sources of history and knowledge. Likewise, storytellers demonstrate that the diverse and manifold roots of history surround us all. OurStoryBridge contributes to efforts that help us share and listen.

Kelly Bartlett is Project Coordinator for OurStoryBridge, working to establish meaningful connections with educators, librarians, historical societies, museums, volunteers, and issue-based nonprofits wishing to begin OurStoryBridge projects. A graduate of the University at Albany’s Information Science and English Program, she enjoys the interdisciplinary functions of OurStoryBridge. Her academic and research interests include community archives and the efforts of professional and amateur archivists to preserve the voices, narratives, and lessons of underrepresented populations.

Jery Y. Huntley received her education and MLS degrees at the University at Albany, but her career took a different turn after her early start as a school and public librarian. She moved back to Albany to work for the NYS Assembly, then headed to Washington, DC, for a position in the U.S. House of Representatives. This led to opportunities in environmental lobbying, issues management, 20 years as a trade association CEO, and volunteer work as a trainer in meeting facilitation and with Habitat for Humanity International. She lives in Washington, DC, and Keene Valley, NY, and her volunteer work now includes her role as Founder and President of OurStoryBridge Inc.

Janelle A. Schwartz brings over two decades of experience as an interdisciplinary educator, program developer, and creative consultant to her work as a freelance project strategist, writer, and editor for JAS Creatives LLC. She holds her PhD in Literature and the History of Science and has published widely on literature and ecology, social justice, the Adirondacks, pedagogy, natural philosophy, and more. She taught Literature and Environmental Studies at Loyola University New Orleans and Hamilton College. She founded and directed the Hamilton Adirondack Program, a place-based, experiential semester and helps 8th– and 12th-graders at Keene Central School tell their stories.

URLs

OurStoryBridge https://www.ourstorybridge.org

“History and Perspective,” by Darren Parry

https://app.memria.org/stories/public-story-view/60810c77daee43cd8c89910c4fe5e8a1

Memria https://www.memria.org

Teacher’s Guide https://www.ourstorybridge.org/tool-kit#4

“Olympic Dream Fulfilled,” by Tommy Biesemeyer

https://app.memria.org/stories/public-story-view/33d329b1cf074994a92be7ef5fa2bf0d

“Meeting John & Mary Brown, Abolitionists,” by Greg Artzner and Terry Leonino—Magpie

https://app.memria.org/stories/public-story-view/4e8089c8f1394e4685ce2183890f532c

“The Underground Railroad in the North Country,” by Jackie Madison

https://app.memria.org/stories/public-story-view/057dacb2bb7946b9ab65de4000c00c95

“Lake Placid & the 1980 Olympics,” by Jim Rogers

https://app.memria.org/stories/public-story-view/2777a538c1bf433ba6d1115e3ab3916e

Igiugig Story Bridge https://www.igiugigstorybridge.org

Life in the Islands https://northherolibrary.org/life-in-the-islands

ADK Voices http://adkvoices.org

Freedom Story Project http://freedomstoryproject.org

“Citizenship,” by Cal Page-Bryant

https://app.memria.org/stories/public-story-view/9f0d51779b2c4c60b6d53da8d825efaa