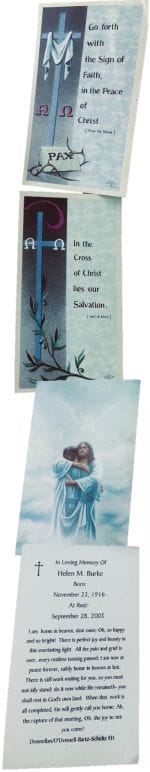

Loss is often mitigated by the real presence tied to prayer cards given in remembrance of the deceased.

This article engages with secularism in an attempt to create openings for teachers, students, folklorists, and researchers to think differently about how reverberations of death, loss, and remembrance are registered, and thus navigated, by people holding scriptural commitments. Although religious frameworks—and the concepts embedded within—serve as a kaleidoscope for engaging with worldviews orientated around perspectives of the divine, they can also be capacious for thinking about entanglements of social phenomena (e.g., the January 6 insurrection) and memory. To better understand how secular concepts intersect with the themes of this special issue of The Journal of Folklore and Education, I reached out to Kevin J. Burke, whom I have known several years.

Kevin earned his PhD in Curriculum, Teaching, and Educational Policy from Michigan State University and is an associate professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. Considering his expertise in teacher education, religion and public schools, and youth participatory action research, I thought Kevin would be the perfect person to illuminate the nuanced ways that death, loss, and remembrance are understood in religious contexts, specifically, Catholicism. He did not disappoint. What follows is the result of our conversation on temporality, transcendence, religious traditionality, and how visual ethnography (PhotoVoice) might be a productive tool for spatial engagements of death, loss, and remembrance. The text has been edited for length and readability.

Bretton Varga: Thank you for making time to hold space with me today. Let’s begin by exploring what piqued your interest in the themes for this issue on death, loss, and remembrance.

Kevin Burke: You may know this from our previous conversations, but some of my work involves engaging with the ways in which education has limited itself and thinking about how to encounter people in extremis. While I’m not particularly interested in grief in this situation, I do think it’s important. Broadly, the idea that education has limited itself, particularly in its neoliberal turn, to thinking about education as a rational endeavor means we’re dealing with human beings who are inherently rationalizing irrationality. I find it most fascinating to look for different lenses to think about how people interact with education and think through education.

My work is particularly in relation to literacy and religious literacy, so that confluence that you all are writing about in this issue I find profoundly interesting in large part because it’s not something that we can measure, but that which is measurable may not be particularly valuable in relation to the educational project. So, I’m always fascinated by thinking differently about how to engage education through new languages and often irrational ones.

BV: I appreciate that and thinking differently resonates with me as it is the primary impetus for our work with this issue. In one of the spaces in which my fellow guest editor Mark Helmsing and I work, think, and write—social studies education—all we do is talk about dead people and the past, yet death itself is rarely acknowledged, engaged with, and/or accounted for. We’re also seeking new ways and new lenses as you mentioned. This leads me to the next idea. American history and Catholic studies scholar Robert Orsi (2016) suggested the importance of attending to the thought of “when the transcendent breaks into time” (111). Can you speak to this notion of transcendence and time in the context of death, loss, and remembrance?

KB: There are ways to engage time, in this case I’m thinking about chronological time and then kairotic time. In this way, chronological frames of temporality are linear and then kairotic time, in a religious sense, would be God’s time, but it is essentially when possibility exists for new things to happen, or rather it accounts for the stopping of linear time for a more expansive sense of possibility to occur. When I think about time in relation to Orsi’s work—he’s writing about transcendence and immanence and the emergence of the sacred into the world. While I believe we have a poverty of language in educational research, curriculum studies and curriculum theorizing allow us to think with the emergence of immanence or transcendence or the sacred conceptually to consider the stopping of linear time.

So, what does it mean to feel time differently? This parallels themes in this issue and interests me immensely. In particular for Orsi, he’s looking at Catholic manifestations of religious experience, but essentially he is suggesting that we don’t necessarily have a language—his field is history but I think of it in relation to educational research—for dealing with the fact that our students and teachers—teachers in particular who are more religious than the general population—will have this potentially profound sense that God exists in the world and as God irrupts into the world, according to Orsi, we need to be able to think about and with what that means.

As I said, rationality isn’t the point. The point is this aspect of experience of the emergence of the divine or the sacred into the world which cuts across religious traditions, including nonreligious ones as well. And I think that we need to know how to think with these ideas and positions in educational research.

BV: Sticking with transcendence and immanence, could you unpack those ideas a bit for readers who are not familiar with them as concepts?

KB: I mean, immanencies are really about the emergence of the divine into the world. So, a lot of what I engage with are the ways in which theologians and anthropologists have created an artificial distinction between the sacred and the profane. The idea has been that the sacred lives somewhere separate from the world and the profane is where we are. The anthropologist Talal Assad suggests that that’s a category error, a misunderstanding of the way in which people—particularly in Christian traditions—originally understood the sacred as abiding in worldly time. Immanence is attending to the ways in which the religious exists and persists in spaces. Transcendence is related. You can think about the ways in which boundary making breaks down through transcendence. God exists beyond comprehension and thus transcends our conceptual categories. I use them interchangeably in ways that perhaps theologians wouldn’t, but I find the pairing helpful because of how transcendence suggests moving across boundaries in ways that immanence doesn’t, at least initially. And then the notion that those boundaries actually are artificial is really important. People have constructed and continue to construct them in our understandings of the world—particularly in relation to secularism—and we could deconstruct them if we wanted to. That is, if we wanted to attend to the sacred as it continues to be emergent.

BV: Yes, and I think, especially considering the context of death, loss, and remembrance, the notion of eroding boundaries, borders, and barriers is significant. Generally, Mark Helmsing and I write about hauntings in ways that are less concerned about paranormal framings and more concerned with attending to the spaces of in-between-ness that are so often unaccounted for in educational contexts. And in our work we argue that these liminal spaces can be constructive in getting us to think about the world in different ways. I see transcendence as an adjacent concept—movement between life, death, the unknown, and so forth. Fascinating stuff.

Narrowing the focus here, how do the sacred, the secular, and the transcendent offer different ways of thinking about death, loss, and remembrance? And how might these concepts help teachers attend to local productions of knowledge of death, loss, and remembrance?

KB: Let’s take the pending Supreme Court case Kennedy v. Bremerton School District. This is the school prayer case that could possibly undo 70 years or so of jurisprudence around adults praying in schools and opens up new modes of religious proselytizing. The assumption and error that I would suggest the progressive left has accepted as a framing from the religious right, is that public schools have become secular spaces over time. As a result of this elimination of religion in schools, this frame suggests, adults have been circumscribed from praying actively in front of their students. And thus, the schools have become secular because religion has, somehow, been eliminated from schools. However, there are multiple secularisms that exist and they exist in particular relation to the religions with which they co-develop. So, secularisms are inherently religious endeavors because of the way in which they become shaped by the sacred traditions around them.

The larger question, in relation to thinking about teachers in schools and loss and death, for me is that we have lost a sense that the sacred always already exists in education in large part because of the people who are in that space. Also, because how we talk about education cultivates this bounded space featuring a strict set of ideals as opposed to a quotidian day-to-day range and battle of ideologies. Attending to the transcendent probably pulls us away from that sort of lofty language regarding the strict ideals embedded in education and pulls us back to the notion that this is an everyday quotidian endeavor of people being with kids in spaces. This is not inherently a secular space, nor a sacred space. Or rather, the space contains, or is contained by, both. It’s just a matter of taking lenses to attend to it. That strikes me as deeply transcendent. For example, if you’re to take seriously the notion that there are people in public school spaces who assume that God, like my mother who grew up Catholic and had to leave space for like angels on her chair, exists, we could also think about how in ignoring these worldviews, we lose a great deal. Here I am speaking pedagogically—or rather that it’s not inherently a religious orientation to account for religious practice or belief, so much as it is an acknowledgement that these religions and secularisms sit nested together.

We can do vital work by using transcendence a little bit differently. We can use transcendent work to think about how those spaces, as you talked of earlier about hauntings, contain boundaries that aren’t neat and clean. It’s actually within in-between-ness that we are able to find really interesting possibilities. I don’t know how that gets us out of the current white Christian nationalist movement, which is quite frightening. But it does allow us different tools to think with kids and teachers who come to us with certain kinds of beliefs. Otherwise, we lose the possibility to communicate with people deeply convicted to their religion who emerge from particular faith traditions.

BV: I think that is a really important thought and it resonates a lot with me, just this idea of thinking with the theories behind those concepts as a mean for opening up spaces in education. I think that we both would probably agree that openness is lacking in education. Specifically, I am thinking in both curricular and pedagogical contexts that are under attack by legislative efforts seeking to keep control and further manipulate critical thought in classrooms.

KB: I’ve been reading a lot about white Christian nationalism (CN) post-January 6 and there is an aggrieved sense of fear and loss from certain versions of white Christian America. Essentially, it’s fear of status loss. And it’s not irrational, as there is the possibility of status loss in large part because of the ways in which some institutions have become through hard work, not naturally, progressive over time. The responses to this potential status loss from practitioners of CN I think are abhorrent, but it is also true that generally speaking when we think of, for instance, Pentecostal Christianity and speaking in tongues, people who come from that faith tradition are not wrong to think that they are looked down upon by a good portion of the educational establishment. I think in the world, this is not to say that there we can’t take a moral stance, but it is to say that understanding the speaking in tongues sociologically, it’s something that occurs as a part of a discourse, which makes it possible in certain kinds of literacies. It’s also important to understand that people in those faiths are experiencing the sacred, the transcendent, and the immanent emergence of God in the world. This is not a false consciousness and it’s not stupid. It’s not irrational; we should be able to think with that and then also make different kinds of arguments for a political future that engages with it in serious ways. It’s not a straight line from direct experiences of disdain from individual educational actors to 80 percent, or whatever, of white Evangelicals voting for Trump. And that’s not saying that the reason that this happens is because teacher educators don’t know how to deal with religious students, but rather it is to say that fear of condescension is in many cases a well-earned one.

BV: I’m glad you brought up events from January 6. I can’t help but contemplate about how thinking with the transcendent and the secular adds an interesting layer for teachers to consider when they are unpacking remembrance around the context of both contemporary and historical events. Could you speak a little bit more about this specific event? In particular, do you have any advice for teachers who are committed to engaging with the concepts you have discussed today in the classroom? And how might a teacher grapple with these ideas and, in turn, put them together to help students think differently about the insurrection of January 6?

KB: The first thing I’d say is that there’s a great deal of work for teachers that’s relatively accessible that suggests that religious practices are literacy practices. You become part of a discourse community and then, thinking of Sara Ahmed’s work, you have lines of orientation that make it more likely that you’ll move in a certain direction based on those discourse communities. Religious ones are particularly powerful. And those were cynically manipulated in relation to January 6, but I still think they are of importance. There are genuine belief systems that are very troubling that we cannot possibly understand unless we are conversant in the theologies that people embrace. We don’t get conversant in those things unless we start reading theological texts. So, from the standpoint of teachers, it’s what we always do in a community—you become embedded in the community; you come to understand the kids, parents, and their families and the discourses out of which they emerge. And then you introduce them to critical tools, which may or may not be embraced, to understand texts differently.

The danger is that we also, on what you might call the political left, have a theory of conversion that is often similar to the conversion narratives that exist in religious spaces. It’s the mentality that “I will introduce you to new knowledge and then all of a sudden you will have the scales fall from your eyes and suddenly you’ll be different.” It just doesn’t work that way, nor should it. And it’s very unsatisfying, because we also have these salvation narratives which we embrace that take the position that if you don’t convert kids to social justice or to becoming better at standardized tests, you have failed. Your failure is because you did not work hard enough. The best advice I have is that teachers have to read the same texts that their students are engaged with, and to a certain degree, engage with students’ media. From there, teachers can begin to help students think critically. I’m in Georgia. A lot of my students talk a lot about Bible study and God and, so I have lots of conversations about religion. The purpose is not to say to them, “Hey, there’s a different or better religion there,” but rather, “I’m a fellow traveler on a religious journey. I have a similar language.”

I may think differently about problems, but it’s not a satisfying hard stop. We’re not going to move people away from those discourses by sneering at religion and by misunderstanding how the sacred

might exist in the world for some people. If we can’t engage in parallel discourses with certain kinds of theologies, we’ve just given up. Multicultural education is a priority yet nobody talks about the religious backgrounds of kids. Which to me is absurd and a real loss. Which brings me back to why I was interested in writing for this issue. Between what we’ve lost and what we really have, perhaps you can mourn it as a death, we’ve lost the ability to have these conversations in large part because either we don’t know how to engage with them ourselves as teacher educators, we refuse to engage them, or we just don’t know how to train people to engage them.

BV: This is fascinating and why I was excited that you agreed to speak with me. There’s so much there and it has me thinking about the anti-racist, anti-oppressive approaches to education that I work to facilitate with my teachers. Something I hear often is that our teachers are ready to change to world, but then they get in front of their classes with real human beings and they struggle with applying their learnings. Teachers then resort back to relying on materials that are whitewashed and reproduce a problematic educational narrative that we both know is extremely limited in various ways. And talking teachers through this, they mention, “I don’t want to mess up,” or “I don’t want to say the wrong thing.” I think perhaps religious and death-related contexts may also fall into this camp of trepidation. I love how you framed one of your comments about “being a fellow traveler.” Moreover, I think regardless of where you’re at spiritually, we are all fellow travelers in life and death. It also…

KB: I think the underlying project right now for anybody who’s doing social justice work is that you are pushing actively against the white Christian nationalist project. It’s 40 to 50 years of really concerted right-wing strategic organizing around religion and ideology and politics. If you cannot, other than through dismissal, engage with the religious language and the theological concepts that undergird all of that, it is a problem. By not engaging, you’re missing all of the nuances for how you could argue from the inside that’s troubling. Anyway, I cut you off. Sorry.

BV: You just reminded me of another situation that connects to this conversation. I’ve encountered teachers who may say that they are uncomfortable engaging with LGBTQIA+ histories, because it goes against their religious beliefs. And it’s almost like this excuse to not do the work that needs to be done because of this secular conflict.

KB: We may think of it as an excuse, which in some sense it is, but it is more complex than that. Heidi Hadley has this wonderful book out called Navigating Moments of Hesitation: Portraits of Evangelical English Language Arts Teachers. Hadley looks at three Evangelical teachers and their relation to two LGBTQIA+ issues in the classroom. Bob Kunzman (2006) also writes about this in his notion of ethical dialogue and how we have to approach it as if these are genuinely deeply held beliefs. Because they, like one of the young women with whom Heidi was working, believed that if she did not do the work of conversion, if she didn’t proselytize, she was consigned to hell. Like that’s no joke, if you think you’re going to spend eternity burning in a lake of fire.

If you believe something like Heidi’s interview subject then my not engaging in religious language at all is not going to convince you of anything, nor should it, quite frankly. The strength of the moral argument that says, hey, don’t discriminate against LGBTQIA+ students here just doesn’t match with the strength of the moral or the religious argument that’s tied to hellfire. I think people’s

willingness to think that this is a satisfactory solution will vary. For example, and this is from Heidi again, there is an Evangelical teacher who has a student who’s going through a transition. And the student really loves this teacher and the teacher really values that student. The student asks the teacher to use their preferred pronouns, and the teacher spends the entire year addressing the student by their name. Pronouns aren’t used at all. Here you have a version of a solution that maintains the teacher’s particular religious commitment while affirming the student. It’s not ideal, but the student feel supported. Do you know Stephanie Shelton? She’s at Alabama and some of her research is on allyship in early teacher educators.

BV: Yes, I have met her! We were both in a session this past year at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference in San Diego.

KB: Her early work involved a teacher that knew they were going to be a certain kind of LGBTQIA+ ally before they went into the field. And then they went into the field, and they realized that to be an ally, in that space, they needed to become a different, quieter kind of ally than they originally thought. One example is that this teacher, and I hope I’m representing Stephanie’s research correctly as it’s been a few years, was going to have a safe space sticker on the door but then the queer kids didn’t come to the space because they thought people would stigmatize them. The teacher had to find a different way to become an ally. Often, my concern is that we send kids and even teachers out with one version of what a good ally or what a good social justice teacher looks and sounds like. And often it doesn’t comport with the reality of the situation that you have to do different kinds of work. We have to prepare students to be flexible, to give up on a sense of who they would have been as a teacher, but also allow them a little bit of leeway in terms of problem-solving capabilities. The hope is to have teachers take the position that “I believe deeply in these ideas and I’m going to get embedded in this community and understand ways to intervene that are more productive and protective of my students.” So, from my standpoint, in terms of how we’re talking about being in a deep red state or religious space, you’re going to need to know the language being used, its roots, and potential counterarguments that emerge from those roots. Then we might be able to differently reconceptualize immanence or transcendence in the classroom or religious possibility in secular spaces.

BV: I think holding transcendence in conversation with haunting might be generative. Here, I’m thinking in terms of the blurring of these very strict temporal demarcations: past, present, and future. Another observation from my end is how teachers seem to think that a safe space sticker or the fact they’ve been an ally for one student, makes their space forever safe or brave. I hold the position that safeness and braveness are always fleeting. They are always in flux, always contingent upon all the moving parts coming in and out of the classroom. Mark’s and my work with ghosts and hauntings also attends to this idea and gives us a lens for thinking about different ways to erode closed structures and mentalities that limit possibility, which returns us to remembrance. How do we remember the pastpresent in ways that will continue to re-shape the future?

Let’s shift toward research methodologies. I came across a piece that you wrote in 2018 about Photovoice and bring it up because ethnography is a key approach folklorists use. You’ve written in the past on visual ethnography, or PhotoVoice, to engage with youth perspectives of spatial inequalities. Can you speak to the potential of PhotoVoice for exploring the context of this issue, specifically, the role of ethics in PhotoVoice with sensitive topics such as death and loss?

About PhotoVoice

Using images, this Participatory Action Research methodology makes visible stories and truths, often for social change.Case Studies

Empowering the Spirit

Deep Center

Practical Methodology Resource

Community Tool Box

Academic Frameworks

A Review of Research Connecting Digital Storytelling, Photovoice, and Civic Engagement. (Greene, Burke, and McKenna 2018)

Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Inquiry with Youth and Communities. (Paris and Winn 2014)

Doing Youth Participatory Action Research: Transforming Inquiry with Researchers, Educators, and Students. (Mirra, Garcia, and Morrell 2016)

Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion. (Cammarota and Fine 2008)

KB: In that project (Greene, Burke, and McKenna 2018) we wanted to use multiple affordances because we thought they would allow participants to talk differently about social change in various spaces. Sometimes, we’d ask them hard questions and send them out with cameras. They would then come back with no pictures, because we’d forgotten that you have to build relationships for people to feel comfortable with what you are asking them to do. So the project went from walking tours with kids and cameras to found poetry as a result of those walking tours. Then it became mapping as we found that different affordances were needed to tell different kinds of stories in those spaces. From an ethical standpoint, it is important to think about who gets represented in those photos. Which, to be perfectly honest, I don’t see as markedly different from the ethical concerns we should have with any kind of qualitative research—particularly with minoritized communities or communities that are explicitly disempowered in certain ways, like youth.

I think that in terms of loss and death…I hadn’t thought about PhotoVoice in relation to that context. That’s super interesting to me. From the standpoint of the Catholic perspective, I can’t help but think about prayer cards, and Orsi writes about this. They’re primarily given out at funerals. They often have representations of saints or the Sacred Heart of Jesus or Mary on the front, and then the name of the deceased on the back along with a quote from the Bible. And, interestingly, these cards become collector’s items. I have them as bookmarks all over the place in my office, which is a really weird kind of thing but still something that could be considered an everyday encounter with death and remembrance. They are almost like death trading cards. And so, it’s not a photographic representation of the person, but certainly could be conceptualized as a snapshot of their life that chronicles someone’s birth and death. There’s no story about the person on the cards, other than “Hey, here’s this moment to remember this person who you haven’t thought about for a while.” It’s almost a reemergence of the person into a life through these cards. Which I know is different from what you asked about PhotoVoice, but I think it is still interesting. Returning to Orsi, what if we take seriously the connection of a person to the Sacred Heart of Jesus? And how might the encountering of these cards establish the deceased’s reemergence back into our lives? I honestly think there are all sorts of different possibilities when we think about how the dead continue to exist in various ways with the living.

BV: I think those are great questions for our readers to sit with and that this is a good stopping point. This has been wonderful and thought-provoking and I greatly appreciate your time.

KB: Thank you for reaching out.

Kevin Burke earned his PhD in Curriculum, Teaching, and Educational Policy from Michigan State University and is an associate professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. ORCID 0000-0003-0941-0113

Works Cited

Cammarota, Julio, and Michelle Fine. 2008. Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion. London: Routledge.

Greene, Stuart, Kevin J. Burke, and Maria K. McKenna. 2018. A Review of Research Connecting Digital Storytelling, PhotoVoice, and Civic Engagement. Review of Educational Research. 88.6:844-78. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318794134.

Mirra, Nicole, Antero Garcia and Ernest Morrell. 2016. Doing Youth Participatory Action Research: Transforming Inquiry with Researchers, Educators, and Students. London: Routledge.

Orsi, Robert A. 2016. History and Presence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Paris, Django and Maisha T. Winn, eds. 2014. Humanizing Research: Decolonizing QualitativeIinquiry with Youth and Communities. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Urls

Empowering the Spirit https://empoweringthespirit.ca/photovoice-project

Deep Center https://www.deepcenter.org

Community Tool Box https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/photovoice/main