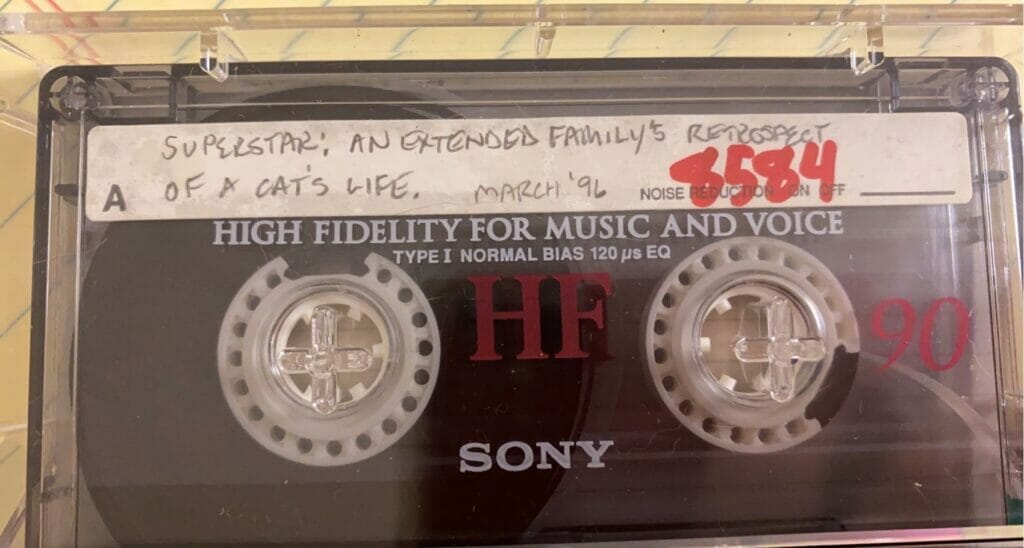

Student Ethnographic Project (SEP) Collection cassette tape, featuring narratives that immortalize a family’s incredible cat. Photo by Jordan Lovejoy.

Introduction: Archives and the Culturally Responsive Classroom

Instructors of Language Arts, History, and Social Studies in the United States are tasked with helping their pupils compare perspectives across time and space. They must teach students how to locate and contextualize varied source materials–and help them develop research, writing, and citing strategies in the process. Standards of learning across the country also require students to analyze claims and practice writing for specific audiences, and to explain and analyze important social issues in the present and recent past, including civil rights, gender politics, technological and institutional change, and human migrations (for example, Virginia’s K-12 Standards & Instruction and Ohio’s Learning Standards for English Language Arts, 2017). Allowing students to explore, interpret, and create ethnographic materials is one way to achieve all these objectives.

Large ethnographic archives, including materials provided online by the Library of Congress, offer enormous and often easily accessible riches to K-16 faculty and students. But we implore teachers interested in creating culturally responsive classrooms not to overlook smaller archives, which often foreground place-based local knowledges and permit both research with existing collections and new community-centered documentation. Diverse perspectives—such as those offered by oral histories—have been shown to stimulate widespread positive outcomes in the classroom and beyond, including creativity and civic engagement (Phillips 2014; Wells, Fox, and Cordova-Cobo 2016). But building on varied local knowledges is especially beneficial for minoritized students, whose cultures and experiences are too often perceived by educators to be deficits. Encouraging students to learn and share information about their own families and communities can create a sense of belonging crucial for “engagement, learning and productivity” (Bowen 2021); more broadly, this kind of sharing encourages all students to “recognize the essential humanity and value of different types of people” (Lynch 2016). And teachers who get to know their students in this way have an upper hand when it comes to making course content and strategy adjustments.

In this essay, we explore what is to be gained from working with ethnographic collections that are relatively “bottom-up” in their orientation and structure. We discuss ways to access local collections and outline the mutually beneficial aspects of developing partnerships with local archives. Most of the article, however, offers a practical glimpse into how we have used The Ohio State University’s Center for Folklore Studies (CFS) Folklore Archives, a repository that has been collecting materials about everyday life in Ohio (and beyond) since the early 1960s. Borland is currently director of CFS, and Christensen and Lovejoy both taught folklore courses in the English Department earlier in their careers. We detail how we used a scaffolded approach to analytic writing that incorporated fieldwork as well as comparative archival research.

In addition to sharing what we learned as we worked to integrate archives into our classrooms, we also provide assignment prompts that can be modified to support learning outcomes for both introductory college composition courses and upper-level high school History and English Language Arts classrooms. Like folklore forms that have been tried and tested through the process of transmission yet are always dynamically adapting to new contexts, we encourage you to take these basic assignment structures and populate them with content attuned to your own needs. As we note below, archives are inherently collaborative institutions, and our best use of them is also collaborative. Thus, we encourage working closely with a local archivist as you develop and modify archive-centered assignments. By doing so, your assignments can address specific learning goals but also take full advantage of the strengths and affordances of the materials available.

Like folklore archives elsewhere in the country, the archive at Ohio State is linked to a curricular folklore program and consists primarily of student-initiated and -defined ethnographic projects. The largest collection, the Student Ethnographic Projects (SEPs), consists of term papers going back to the 1960s. The projects offer snapshots of student interests, campus life, and responses to historic events, and they address myriad topics, including rules for toilet-papering a house and documentation of Dungeons & Dragons gaming traditions (Image 1). While the collection is a trove of youth culture, it also contains interviews with elders from students’ families, hometowns, and workplaces. Because Ohio State’s Introduction to Folklore class requires ethnographic research, student papers typically include at least one audio interview, rich contextual descriptions of practices from everyday life, and sometimes photographs or ephemera. Thanks to many, many student archivists who have labored to keep our archive organized, the SEP Collection is keyword searchable. As we discuss below, our students have not only produced materials for the archive, they have also used existing collections to develop research, writing, and analytical skills.

Image 1. 2022 CFS archivist Jasper Waugh-Quasebarth displays a Student Ethnographic Project (SEP) with original artwork. Photo by Jordan Lovejoy.

But are the SEPs online? you may ask. And if not, how can they be useful to me if I’m not in Columbus, Ohio? Because we want to ensure that our materials are used respectfully and according to the wishes of research subjects, and because we lack permanent staff (a feature of many bottom-up collections), most of Ohio State’s folklore archive is not immediately available online. However, online galleries and finding aids describe the collections, and we welcome email inquiries and requests for in-person or online visits. Archives of vernacular culture may also exist closer to you, since universities with folklore programs typically manage materials very similar to ours, and some also have online collections. (See Appendix for a list of some archives that we have identified, as well as an invitation to crowdsource an expanded list.)

Image 2. OSU Geography professor Kendra McSweeney and her students examine letters from an early 20th-century mixed-race mining town in Southeast Ohio (a collaboration between donors Janis and Harry Ivory, Black in Appalachia, and the CFS Folklore Archives) during a 2020 class visit.

Photo by Megan Moriarty.

Alternatively, your nearest university may have an oral history center with interviews and other materials related to local culture. Also look for community archives related to specific groups that may help your students see their own (or new) cultural experiences reflected in documentation and preservation practices. For instance, Black in Appalachia offers a podcast and online archives of Black life in East Tennessee. Moreover, it supports local documentation and archiving initiatives throughout the Appalachian region (Image 2). The South Asian American Digital Archive includes a wealth of materials assembled by individuals, families, and organizations. Museums and libraries often provide online access to a range of primary sources they have identified, as in the personal narratives, videos, and songs about coal company towns in lesson plans created by the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. These are just a few suggestions for digitally available community archives that you and your students might find interesting. Local, county, and state historical societies may offer online access to primary materials as well, if you are not able to arrange a visit in person.

Once you identify a bottom-up archive close to you, make contact. Remember that these kinds of archives are often under-resourced labors of love, so have an exploratory conversation with archive staff to gauge whether your pedagogical goals can be met using the archives’ resources. Developing curricula in conversation with an archivist can ensure that your plans are reasonable and doable and that they align with the learning standards at your institution. Ideally, the archivist could visit your classroom, or your students could visit the archives for a presentation or an encounter with research materials. The CFS Folklore Archives, for instance, has hosted Columbus City Schools students from Mosaic, a high school program that encourages self-directed humanities exploration using the city as an experiential classroom. Our archivists use examples from the SEP Collection to get students thinking about their own community cultures. Mosaic students also learn about archival practices and issues related to the documentation and preservation of everyday life. If an in-person field trip is not possible for you, consider arranging a similar presentation via Zoom, or ask about other options for collaboration.

By exploring archived materials, students learn research skills and discover new content—but archives also benefit. When making a case for financial and staff resources, archive directors can point to your visits as proof that the materials they steward are both important and used. Working with local organizations also facilitates new assignments that can be built and modified over time to enhance learning outcomes. So, it is worth reaching out and developing a mutually beneficial pedagogical relationship with archivists in your area.

Below, we offer several examples of how we have used Ohio State’s folklore archive in college classrooms. To aid you in developing your own ways to teach using sources from your local archives, we include assignment guidelines and support materials we created for first- and second-year college students. Because the learning objectives in college introductory composition courses are similar to those of upper-level secondary History and English Language Arts classrooms, these assignments can easily be modified for high school students as well.

Image 3. Archivist Rachel Hopkin introduces students visiting the CFS Folklore Archives in 2020 to the numbering system for the SEP Collection. Photo by Megan Moriarty.

Using Archives in the Classroom

The CFS Folklore Archives is constantly evolving, sustained in part by decades of English Department folklore courses that teach students the foundations of writing a research paper and conducting ethnographic fieldwork. This student documentary work comprises the SEP Collection. Christensen and Lovejoy brought these materials back into the classroom by building work with Ohio State’s existing SEPs into their versions of a second-level writing course called English 2367 (Language, Identity, and Culture in the U.S. Experience). All sections of this course develop critical-thinking and careful communication skills within a specific academic field, helping students synthesize primary and secondary sources through scaffolded writing assignments. The course stresses analytical strategies such as inductive reasoning and making the implicit explicit, while also expecting students to engage concepts and approaches germane to a particular discipline.

Christensen and Lovejoy both taught a subsection of English 2367 called “Writing About the U.S. Folk Experience.” English 2367.05 couples important folkloristic concepts (such as group, dynamic tradition, genre, performance, power) with fieldwork (observant participation, documentation and reflection, interview and transcription), asking students to reflect on how cultural documentation, as a form of new knowledge production, contributes to their critical-thinking and communication skills. The authors designed SEP-centered assignments to facilitate student success in these areas by drawing on students’ personal experiences, introducing peer models for comparison, and encouraging interrogation of received versions of history.

In her classes, Lovejoy used the SEP Collection to provide examples of other student research papers and help students produce expository writing in an accessible environment. Christensen’s students developed and prepared their own portfolios for accession by the archives, using several archive visits to locate supporting evidence and to examine strategies of ethnographic representation. Both teachers capitalized on the ways the SEPs provide comparative data and allow student researchers to engage issues and objectives germane to Social Studies and Language Arts classrooms. For instance, as students think through the traditional and dynamic elements of folklore, they examine how stories, beliefs, and practices transform over time as they are transmitted and reshaped across groups, networks, and places. Youth culture is not often visible in historical records, so the SEPs simultaneously validate students’ life experiences and allow them to speak with authority about the ways that youth and young adult practices have shifted in response to current contexts. Below, Lovejoy and Christensen offer specific descriptions of their different approaches to the same materials, demonstrating the varied possibilities a folklore archive can offer.

English 2367.05: The U.S. Folk Experience, designed for 2nd year+ university students, explores “concepts of American folklore & ethnography; folk groups, tradition, & fieldwork methodology; how these contribute to the development of critical reading, writing, & thinking skills.” (Excerpted from Course Catalog, https://english.OSU.edu/courses)

Writing the Student Ethnographic Research Paper

In her English 2367.05 course, Lovejoy chose to incorporate fieldwork and ethnography training into research-based writing. Required textbooks included Lisa Ede’s The Academic Writer: A Brief Guide (2016) and Lynne S. McNeill’s Folklore Rules: A Fun, Quick, and Useful Introduction to the Field of Academic Folklore Studies (2013). Each student also collected and analyzed examples of vernacular expression early in the semester, based on personal interest. Documenting verbal art, material culture, and customary behaviors can deeply engage students in research practices by encouraging them to examine events or processes from their daily lives, thus expanding notions of what can or should be studied in an academic context.

During the first six weeks of class, students worked to define folklore and ethnography, alongside training in fieldwork practices and expository writing. For example, student groups trekked through campus documenting verbal, material, and customary lore as part of a scavenger hunt activity (Classroom Connections, Document 1). In a subsequent class, each group created and presented a persuasive advertisement for the folklore forms they documented during the scavenger hunt (Classroom Connections, Document 2), applying and analyzing several rhetorical strategies in the process. Later, they participated in an ethnography workshop, using a worksheet (Classroom Connections, Document 3) that asked them to immerse themselves in campus, document their (participant) observations, and reflect on their experiences using fieldnotes.

These activities helped meet course learning outcomes that included effective writing and communication, collaboration, and understanding of rhetorical devices. Because many secondary education learning standards are also focused on communication and research skills, these activities can easily be modified for use in upper-level high school classrooms. For example, Ohio’s Reading Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects for grades 11-12 include a focus on citing, analyzing, evaluating, and integrating primary sources into student work. The ethnographic research tasks described above support those standards by further developing a student’s ability to analyze and employ argumentative strategies and persuasive appeals into written, oral, and visual communication through critical analysis and discussion, including conversation and collaboration with their peers.

After this preparatory work, the class visited the CFS Folklore Archives to engage with the SEPs. The CFS provides several resources and teaching tools for instructors, including an assignment designed to help students use archive materials. This site-specific assignment asks students to choose two existing SEPs related to their individual research topics, then summarize the projects and compare them with their own. In the process, students bolster research skills by learning how to develop keywords and use finding aids. They also reflect on how former students have approached similar topics.

When they visited the CFS Folklore Archives, Lovejoy’s students spent the entire class period reading, reflecting on, and analyzing the SEP examples, looking for interviewing and writing strategies and determining how successful they were, and why. Each SEP usually includes a tape log, audio files, transcripts, and an ethnographic research paper, so students see clear writing examples relevant to their research topics and written by peers with similar skill levels. Lovejoy found that these examples encouraged more student engagement than did an unrelated writing sample she provided.

As Lovejoy’s students built their own ethnographic research papers, this CFS comparative assignment was useful in several ways. Investigating examples of past student life and interests empowered students to see their own research, writing, and life experiences as valuable contributions to knowledge (and they may deposit their SEPs in the Folklore Archives if they choose). These prior texts also shaped the new ones. For example, one student wanted to explore the intersection of family folklore and youth activism. The two SEPs she read during the archives visit discussed similar ideas, so she was able to examine how other students researched activism and conducted interviews with family members, and she generated more specific keywords that helped her find stronger secondary sources for her own paper.

The archives assignment also helped her craft the questions she used when she interviewed her mother about counterculture protest movements in the 1970s and 80s. Based on what she had seen in the archives, she expanded her study to include more kinds of everyday expression. For example, she analyzed how belief is shaped by personal and group experiences, how material culture like clothing is employed for in-group identification, and how what may be seen as youth rebellion in protest practices might evolve into political agency and citizen engagement over the course of a person’s life. Significantly, in reflecting on the project, this student noted how her conversation with her mother revealed that her own political beliefs and protest practices had been informed by those of the prior generation.

This archival, ethnographic, and expository writing process also led this student to discuss how activism burnout often leads to declining engagement in movements for justice, and she argued for methods to prevent burnout—including focusing more on solidarity with, rather than rebellion against, previous generations. The student’s paper challenged the stereotype that only youth engage in activism, fight for change, and demand justice, and she commented that her engagement with previous SEPs, alongside her new ethnographic training, reshaped her thoughts about activist movements throughout history.

The SEP Collection is thus a powerful tool to help today’s students think critically about the dynamics of both expository writing and vernacular expressive culture. In addition to meeting the learning goals related to research writing, such as knowledge of composing processes and conventions, the assignment emphasizes critical thinking, reading, and writing, alongside recognition of how social diversity in the U.S. can shape our attitudes and values toward others. Lovejoy’s use of the CFS assignment also helped students engage with writing produced by academic peers, an important supplement to published scholarship authored by seasoned writers. Importantly, for students who are just beginning to learn both the research process and ethnographic methods, focusing only on a perfect, polished, final product may cause writing anxiety; interacting with peer projects helps students focus instead on research writing as a dialogic and often reflexive process.

Finally, Lovejoy found that collaborating with an archivist on assignments, visits, and materials made the teaching experience smoother and the learning opportunities richer, since teacher and archivist can be sounding boards for one another. The SEPs and teaching with archival material thus challenge assumptions about research writing and pedagogy as monologic products and folklore as a static form, while expanding the scope of whose work and stories are deemed worthy of academic analysis.

Analyzing Framings of Self and Other in Documentary Practice

Christensen taught in the Ohio State English Department several years before Lovejoy, when Folklore Archives staff were still developing technologies and policies to expand the SEP Collection’s accessibility to students and other researchers. At the time, keywords were being standardized and just starting to be required as part of accessioning procedures, and the assignment so helpful to Lovejoy’s students had not yet been designed. Because her course objectives and outcomes were similar to Lovejoy’s, here Christensen draws on several iterations of her course to offer practical tips for guiding students through a multi-visit archives assignment. Explicitly outlining student activities that should take place before, during, and after archives work helps to emphasize and demystify research processes. Furthermore, when created in conjunction with archive staff, these assignments can help repositories develop more efficient or effective processes for working with student researchers.

Like the assignment Lovejoy used, Christensen’s asked students to do comparative work and look critically at archived materials—but instead of explicitly examining writing styles and techniques, students in her classes critiqued modes of documentation and analyzed framings of self and Other. The semester’s textbook was They Say/I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing (5th ed. 2021). In it, authors Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein help students practice summarizing other stances accurately and ethically (“They say . . .” ) while also entering important conversations themselves (“I say . . . ”).

Christensen also wanted students to engage with a “they” beyond the academy. Employing a rhetorical perspective, she asked students to explore not only what people say and do, but also how they say and do it, and with what consequences. For instance, because language shapes how we experience, understand, and order reality, the ways that people have written about and represented “culture” gives insights into the values, assumptions, and social identities of the documenters—not just the documented. In other words, while firsthand interviews, photos, and essays can offer apparently objective data, the ways these materials are “written up” can also reveal social hierarchies and point to relationships of power that fracture along lines of race, gender, age, region, class, professional credentials, and the like.

The first time Christensen taught 2367.05 with this comparative project in mind, the semester’s theme was the (Ohio State) college experience. To explore the identities negotiated on campus by means of expressive culture, students investigated campus life from multiple viewpoints. They drew on the fieldwork of previous students, conducted an interview, observed campus life in the present, crafted an oral presentation for peer feedback, and composed an analytical research paper that brought past and present ethnographic data into dialogue with theory and history. Patterns and genres they discovered in the archives directed their own fieldwork foci; some, for instance, compared the use of similar genres among different groups (pranking in the marching band in 1970 and pranking on the present-day volleyball team), while others looked at the use of a genre in the same group over time (stepping among African American fraternity members in 1970 and in the student’s experience).

However, conducting high-quality research in the archives and learning to do high-quality fieldwork proved challenging, given the time constraints of a single semester, an 80-minute class period, and technical issues that slowed down students’ ability to identify and search archive materials. Consequently, in the next course iteration the fieldwork piece became an exercise in self-documentation. Based on her emerging knowledge of materials available in the CFS Folklore Archives, and assuming that all students would be able to document and analyze some aspect of their own youth culture, Christensen shifted the second semester’s course theme to “Children’s Folklore.”

Discover assignment scaffolding designed to make research and writing processes deliberately explicit and transparent below, including a description of the steps, assignments, and tools that Christensen developed based on student experiences and questions.

Preparing, Documenting, Reflecting: Structuring Archive Visits

At the beginning of the third week of the semester, and in the midst of the disciplinary orientation described above by Lovejoy, Christensen scheduled an exploratory trip to the archives. This visit was intended to help students learn to find and request material. Several readings prepared them for archive etiquette and content ( Langlois and LaRonge 1983, Gaillet 2010), and she provided examples of how to cite primary source materials obtained from archives. During this first and subsequent visits, students had tasks to complete before, during, and after (Classroom Connections, Document 4).

Prior to the visit, students were required to reserve several SEPs, using specific instructions and sample search terms.

During each visit, they listed the title, ID number, date, and location of the SEPs they reviewed; summarized the content of each collection in a few sentences; took notes on unusual or intriguing patterns or connections; and identified topics, genres, and groups that they might want to follow up, and why.

After each visit, students shaped these notes into 400-word discussion board posts. To aid peers interested in similar topics–and to improve their summary and interpretation skills–they gave each post a title that suggested some of the genres and topics they’d explored or that pointed to an emerging analytical issue.

“I’ve Got Folklore”: Self-Documentation Assignment

Immediately after the exploratory visit, students used a template (Classroom Connections, Document 5) to begin documenting three examples of vernacular culture that they had learned before age 15. The “I’ve Got Folklore” (IGF) assignment guidelines (Classroom Connections, Document 6) provided students with a list of common children’s folklore genres. Christensen also provided sample completed documentation sheets: one for verbal art, one for material culture, and one for customary behavior (Classroom Connections, Documents 7-9). The template asks the student to transcribe/describe/diagram their specific example (“item”), figure out its genre definition, offer information about its social and cultural contexts (Bauman 1983), find related examples (“variants”), and comment on the item’s social meanings and functions. Peer review of the IGF documentation sheets helped point out information that was confusing or missing and generated new ideas for both the writer and the reviewer.

“They’ve Got Folklore”: Focused Archive Assignment

Weeks 4 and 5 also included an archive visit, preceded by readings about inferring meaning from patterns and generating plausible interpretations. During these visits, students looked specifically at archived data that corresponded to their own “I’ve Got Folklore” documentation sheets. Sometimes, they created new IGF sheets based on gaps they noticed in the CFS Folklore Archives holdings. Students who documented “fighting games,” bullying and “comebacks,” and “gender tests,” for example, noted that these perhaps less savory aspects of playground culture were not well represented in the existing SEPs. Students also took special notice of the ethics and methods of fieldwork employed by the SEP contributors, as well as the ways the collection authors positioned themselves with regard to axes of power (based, for instance, on how they spoke about research “subjects” or framed particular topics).

The first time Christensen taught this archives-centered class, it became clear that the notes many students took during their visits were far too general to permit close comparisons or otherwise be analytically useful. She began asking students to copy out three specific examples from archived materials during each visit. In addition, she required discussion board posts to suggest how these examples related to students’ own experiences and to the secondary scholarship they were encountering in course readings.

Synthesis: Preliminary Collection Analysis

During Week 6, students turned in a three-page preliminary collection analysis for peer review. In it, they cited two original texts from the archives and analyzed them in comparison with a related example from their own life (occasionally, students needed to create an additional “I’ve Got Folklore” documentation sheet for this example, highlighting the shifting and emergent nature of the research process). This source integration essay asked them to identify specific features of the text/practice that they found interesting or puzzling, and then craft a discussion leading to and beginning to answer a “So What” question, perhaps related to one of the issues raised in assigned readings. The second time Christensen taught the course, she added a crucial fourth visit to the archives in Week 8, after students had received peer review (Classroom Connections, Document 10) of the three-page essay. This final trip allowed students to follow up questions or concerns raised in peer and instructor feedback.

Entering the Broader Conversation

In the second half of the semester, students worked to position their primary data within broader secondary research, creating a relevant annotated bibliography, giving an oral presentation, and revising their analytical essay into a six- to seven-page essay to be submitted to the archives. The essay made a claim about how a specific genre/example worked and why it mattered, using at least four relevant secondary sources to help situate student analysis within an existing scholarly conversation, especially around issues of power, representation, and identity. For instance, students examined children’s song parodies as attempts to navigate power differentials, “seeking games” and tongue twisters as forms of cognitive and social development, and high school football as ritualized aggression. Other students challenged the conceptual approaches of past SEPs, redefining terms like mischief or superstition. For example, one student from southern Ohio analyzed agricultural sayings and weatherlore—often dismissed as superstition—in terms of knowledge transmission and rural identity formation.

Finally, students packaged their project data and analytical paper in an organized portfolio (Classroom Connections, Document 11), contextualized so that it would be useful for future researchers. This final project component not only asked students to write for a specific public audience, but it also emphasized issues of framing and researcher ethics, including the use of proper consent forms and creation of a cover sheet that included relevant keywords and other information required by the archive. To give future researchers a sense of the students’ positionalities, each portfolio contained a biographical statement in which the maker reflected on why they chose their topics and analytical lenses.

Like Lovejoy’s students, Christensen’s students remarked on the validating effects of self-documentation, an increased appreciation for the past’s relevance to the present, and a sense that competent fieldwork and writing was within their ability. Careful structuring of the timing and products of archive visits is crucial to developing this student confidence and capacity—and it also helps to maximize the efficacy of all-too-short archive visits, especially if an archive relies on nondigitized materials and minimal staff.

Conclusion

As these assignments demonstrate, in-person visits to folklore archives can offer students not only content for their research, but also models for successful writing and sophisticated critique, as well as opportunities to contribute new data. These in-person experiences can be modified for student groups that are unable to visit the archives by working closely with archivists to co-develop digital conferencing or slide-based introductory presentations, as well as online access to the materials that students would like to inspect.

Another option for remote participation is to contribute to an ongoing digital collection project. For instance, our University of Nevada colleague Sheila Bock hosts a mortarboard decoration collection on the CFS Folklore Archives website, with clear instructions for anyone who would like to contribute experiences or photographs. Former Ohio State archivist Rachel Hopkin also set up a campus life digital folklore collection, alongside aids for contextualizing these materials. Although that collection focuses on the Ohio State experience, Hopkin’s module and instructions can be easily modified for other campus contexts. Once again, we urge you to chat with a local archivist to explore possibilities for submitting work as well as for doing research in existing collections.

Ohio State’s CFS Folklore Archives provides many helpful tools to make the teaching process smoother and the collaborative process stronger. In addition to the resources discussed above, the archive provides instructions for electronic submission of ethnographic research material, a tape log template, and a transcription guide to support first-time ethnographers, teachers of ethnography, and institutions wanting to standardize their archival donation practices or looking to partner with communities and/or educators.

We close with a consideration of broader reasons for engaging with local archives, wherever you happen to be. Although bottom-up archives may not be as easy to access as more established national archives with large online platforms, they can offer opportunities to engage with aspects of the past that are not always included in these larger collections. In her book Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work (2021), Michelle Caswell argues that archives created by the most powerful members of a society often symbolically annihilate marginalized and oppressed communities by systematically underrepresenting, misrepresenting, or ignoring them. These archives can in fact contribute to the continuing domination of the underrepresented by excluding counternarratives.

Community archives, on the other hand, are often set up by and for marginalized or underrepresented groups, such as tribal nations or LGBTQ+ people. Minimally, Caswell writes, community archives provide a sense of “representational belonging.” Maximally, they accomplish “liberatory memory work,” deconstructing the forms of oppression that have led to underrepresentation and misrepresentation in the first place (2021, 6, 13). Working within the context of the South African reconciliation, Chandra Gould and Verne Harris argue that “the powerful will tend to use memory resources to fulfill the end of remaining powerful” (2014, 5), whereas liberatory memory work makes space for other voices and perspectives to confront historic injustices, insist on accountability, and reveal hidden dimensions of human rights violations.

Folklore archives offer students from diverse backgrounds the opportunity both to learn about local cultures and to contribute to the developing record by documenting their own practices and knowledges. Because students research their own groups, their work bolsters their sense of representational belonging. They also conduct liberatory memory work by valuing what is often dismissed as frivolous and unimportant and by recognizing themselves as possessors and transmitters of knowledge.

Moreover, partnerships with smaller archives disrupt silos that prompt constant reinventions of the wheel; by sharing resources and collaborating with and across physical and institutional boundaries, we enter into a more dialogic pedagogical process. Modeling this kind of pedagogical practice strengthens our ability (and credibility) to teach students collaborative research practices and ethnographic methods. We hope that the resources we offer help foster high-quality expository writing, ethnographic fieldwork, and archive literacy. But these joint endeavors also bolster the sustainability of smaller archives that have a liberatory and inclusive mission. Like public education generally, these institutions are often stressed and sometimes under threat.

As you plan learning activities, we encourage you to partner with and contribute to the archival collections in your neck of the woods, remembering that research is always a collaborative venture, and that we can accomplish more by sharing our classroom-tested tools and ideas than if each of us works from scratch. After the long Covid-19 winter, it is time to get our students out into the world and to bring the world to them. Working with your local bottom-up archive can be an exciting opportunity to build relationships across institutions and disciplines while modeling collaboration for students who can see their own cultural experiences, knowledge production, and everyday life documented in an archival collection.

Katherine Borland is Professor of Comparative Studies in the Humanities and Director of the Center for Folklore Studies at The Ohio State University. ORCID 0000-0002-5073-0429

Danille Elise Christensen has a PhD in Folklore from Indiana University and is Associate Professor in the Department of Religion and Culture at Virginia Tech. As an undergraduate, she earned secondary education teaching certificates in English and Biology. Today her work largely examines the politics of knowledge production, transmission, and valuation, and her publications encompass work on ritualized sport, scrapbook-making, gardening, Indigenous foodscapes, and food preservation. Her forthcoming book explores who has promoted home canning in the United States over the last two centuries, and why. ORCID 0000-0003-3640-400X

Jordan Lovejoy is an American Council of Learned Societies Emerging Voices Fellow, Southern Futures Assistant Director, and Visiting Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She holds a PhD in English with a Graduate Interdisciplinary Specialization in Folklore from The Ohio State University. Her interests include environmental folklife, strategies for environmental justice action and advocacy work, and the literature and artistic expression of Appalachia and the American South. ORCID 0000-0002-0221-0832

Archive Appendix Referenced in Article

We invite readers to help us crowdsource community archives and collections that offer opportunities for teaching and learning using primary sources. Local Learning is maintaining a list at https://Locallearningnetwork.org/TPS. Write us at info@locallearningnetwork.org to suggest additional archives for this resource.

FOLKLORE REPOSITORIES:

In the West

Berkeley Folklore Archive http://folklore.berkeley.edu/archive

Fife Folklore Archives (Utah State University) https://library.usu.edu/archives/ffa

Randall V. Mills Archives of Northwest Folklore (University of Oregon) https://folklore.uoregon.edu/archives

University of Southern California Folklore Archives https://dornsife.usc.edu/folklore/folklore-archives

William A. Wilson Folklore Archives (Brigham Young University) https://lib.byu.edu/collections/wilson-folklore-archive

In the Southwest

Houston Folk Music Archive (University of Houston) https://digitalcollections.rice.edu/special-collections/houston-folk-music-archive

Woody Guthrie Center (Tulsa, OK) https://woodyguthriecenter.org/archives

In the Central States

Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures (University of Wisconsin–Madison) https://csumc.wisc.edu

Indiana University Folklore Archives

https://folkarch.sitehost.iu.edu/index.html

Ozark Folksong Collection (University of Arkansas) https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/OzarkFolkSong

In the South

Appalachian English (Joseph Sargent Hall recordings, University of South Carolina) http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/appalachianenglish/index.html

Archives of Cajun and Creole Folklore (University of Louisiana–Lafayette) https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/ull-acc:collection

Digital Library of Appalachia http://dla.acaweb.org

The Southern Folklife Collection (University of North Carolina Chapel Hill) https://library.unc.edu/wilson/sfc

West Virginia Folklife Program Collection (West Virginia University) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu

In the East

Folklore and Ethnography Archives (University of Pennsylvania)

https://www.sas.upenn.edu/folklore/center/archive.html

Harvard Folklore Collections https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gened1097/Harvard

Northeast Archives of Folklore and Oral History (University of Maine) https://umaine.edu/folklife/archives

Pennsylvania Center for Folklore Collection (Penn State Harrisburg) https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/c.php?g=1082288&p=8002156

Works Cited

Bauman, Richard. 1983. The Field Study of Folklore in Context. In Handbook of American Folklore, ed. Richard M. Dorson. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 362-8.

Bowen, Janine. 2021.Why Is It Important for Students to Feel a Sense of Belonging at School? NC State College of Education News, October 21, https://ced.ncsu.edu/news/2021/10/21/why-is-it-important-for-students-to-feel-a-sense-of-belonging-at-school-students-choose-to-be-in-environments-that-make-them-feel-a-sense-of-fit-says-associate-professor-deleon-gra.

Caswell, Michelle. 2021. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. London: Routledge.

Ede, Lisa. 2016. The Academic Writer: A Brief Guide, 4th ed. New York: Bedford/Saint Martin’s.

Gaillet, Lynée Lewis. 2010. Archival Survival: Navigating Historical Research. In Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition, eds. Alexis E. Ramsey, Wendy B. Sharer, Barbara L’Eplattenier, and Lisa S. Mastrangelo. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 28-39.

Gould, Chandra and Verne Harris. 2014. Memory for Justice. Nelson Mandela Foundation, https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/MEMORY_FOR_JUSTICE_2014v2.pdf.

Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. 2021. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing, 5th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

K-12 Standards & Instruction. Adapted 2017. Virginia Department of Education, https://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching-learning-assessment/instruction.

Langlois, Janet and Philip LaRonge. 1983. Using a Folklore Archive. In Handbook of American Folklore, ed. Richard Dorson. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 391-6.

Lynch, Matthew. 2016. Ways to Promote Diverse Cultures in the Classroom. The Edvocate (blog), April 13, https://www.theedadvocate.org/ways-to-promote-diverse-cultures-in-the-classroom.

McNeill, Lynne S. 2013. Folklore Rules: A Fun, Quick, and Useful Introduction to the Field of Academic Folklore Studies. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Ohio’s Learning Standards for English Language Arts. Adapted 2017. Ohio Department of Education, https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/English-Language-Art/English-Language-Arts-Standards.

Phillips, Katherine W. 2014. How Diversity Makes Us Smarter. Scientific American, October 1, https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1014-42.

Wells, Amy Stuart, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo. 2016 How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, February 9, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students.

Links to Resources, including URLs referenced

All Classroom Connections https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/OhioStateUClassroom_Connections.pdf

Berkeley Folklore Archive http://folklore.berkeley.edu/archive

Fife Folklore Archives (Utah State University) https://library.usu.edu/archives/ffa

Randall V. Mills Archives of Northwest Folklore (University of Oregon) https://folklore.uoregon.edu/archives

University of Southern California Folklore Archives https://dornsife.usc.edu/folklore/folklore-archives

William A. Wilson Folklore Archives (Brigham Young University) https://lib.byu.edu/collections/wilson-folklore-archive

Houston Folk Music Archive (University of Houston) https://digitalcollections.rice.edu/special-collections/houston-folk-music-archive

Woody Guthrie Center (Tulsa, OK) https://woodyguthriecenter.org/archives

Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures (University of Wisconsin–Madison) https://csumc.wisc.edu

Indiana University Folklore Archives https://folkarch.sitehost.iu.edu/index.html

Ozark Folksong Collection (University of Arkansas) https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/OzarkFolkSong

Appalachian English (Joseph Sargent Hall recordings, University of South Carolina) http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/appalachianenglish/index.html

Archives of Cajun and Creole Folklore (University of Louisiana–Lafayette) https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/ull-acc:collection

Digital Library of Appalachia http://dla.acaweb.org

The Southern Folklife Collection (University of North Carolina Chapel Hill) https://library.unc.edu/wilson/sfc

West Virginia Folklife Program Collection (West Virginia University) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu

Folklore and Ethnography Archives (University of Pennsylvania) https://www.sas.upenn.edu/folklore/center/archive.html

Harvard Folklore Collections https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gened1097/Harvard

Northeast Archives of Folklore and Oral History (University of Maine) https://umaine.edu/folklife/archives

Pennsylvania Center for Folklore Collection (Penn State Harrisburg) https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/c.php?g=1082288&p=8002156

Black in Appalachia Community History Archive https://www.blackinappalachia.org/community-history-archive

South Asian American Digital Archive https://www.saada.org

West Virginia Mine Wars Museum lesson plans https://wvminewars.org/lesson-plans

“How to Use a Source: The BEAM Method” https://library.hunter.cuny.edu/research-toolkit/how-do-i-use-sources/beam-method

Scavenger hunt teaching activity handout created by Lovejoy https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Oegim-cqopAjw3ncJ1papcJSoQFjpnar/view?usp=share_link

Folklore advertisements activity handout created by Lovejoy https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pmr2X7vx53gz8sdASba3yWW5XpCirpBt/view?usp=share_link

Ethnography and fieldnotes activity handout created by Lovejoy https://drive.google.com/file/d/1x9exmCQq1JPNtnfb-T2pb5qZNKvKpapF/view?usp=share_link

Ohio’s Reading Standards https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/English-Language-Art/English-Language-Arts-Standards

Using the OSU Folklore Archive Assignment: Instructions for Students https://cfs.osu.edu/sites/default/files/2022-06/using_the_archive_assignment_-_student_instructions.pdf

“They’ve Got Folklore” assignment guidelines (archive notes/reflections and preliminary collection analysis) created by Christensen https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ZgudksWApYHnPjdHNySdC8qrPA-rMMLU/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=100594272009534305491&rtpof=true&sd=true

“I’ve Got Folklore” blank documentation sheet created by Christensen https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-_pw14Jwpufob5YEIQsYjn1A6XBF8kVT/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=100594272009534305491&rtpof=true&sd=true

I’ve Got Folklore” assignment guidelines created by Christensen https://docs.google.com/document/d/1dXStmiBKD_EdKjtTbA_qHLLpZF01AmY-eorGeDfo4oU/edit?usp=sharing

Sample verbal art documentation sheet (“riddle joke”) https://docs.google.com/document/d/1jjZALPfPt57vWxK-EruvbaGRAFyF0OWympQDShKksvk/edit?usp=sharing

Sample material culture documentation sheet (“Fly tying”) https://docs.google.com/document/d/125eZUHqWu-XZL8iyvO9ulLMDPVSL5V37j-4cHDWsiN4/edit?usp=sharing

Sample customary behavior documentation sheet (“Catalina Madelina”) https://docs.google.com/document/d/173tPntD6F8TaX3Df3xH4vIRaHVcRKz3qTnKHKPZYdOw/edit?usp=sharing

“They’ve Got Folklore” peer review rubric created by Christensen https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kjeIOyP7mzd3sVVQGXLYEO90JsOwJrOK/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=100594272009534305491&rtpof=true&sd=true

Self-documentation portfolio guidelines created by Christensen https://docs.google.com/document/d/1CyC7XcicCs7o6H7Pbtfvj7rHJ6mI3EJX/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=100594272009534305491&rtpof=true&sd=true

Mortarboard Decoration Collection in the Ohio State Folklore Archives https://cfs.osu.edu/archives/collections/gradcaptraditions

Student Digital Folklore Collection Course Module in the Ohio State Folklore Archives https://cfs.osu.edu/course-modules/student-digital-folklore-collection-course-module

Instructions for Electronic Submission of Ethnographic Research Materials at the Ohio State Folklore Archives https://cfs.osu.edu/archives/donate/instructions-electronic-submission-ethnographic-research-materials

Master Tape Log Template for Student Ethnographic Projects at the Ohio State Folklore Archives https://cfs.osu.edu/sites/default/files/2020-08/master_tape_log_template_for_student_ethnographic_projects.pdf

Transcription Guideline created by authors for the Ohio State Folklore Archives https://drive.google.com/file/d/19n6FcVvjq9sXQDXphblz_o_Gc4bglj0e/view?usp=sharing