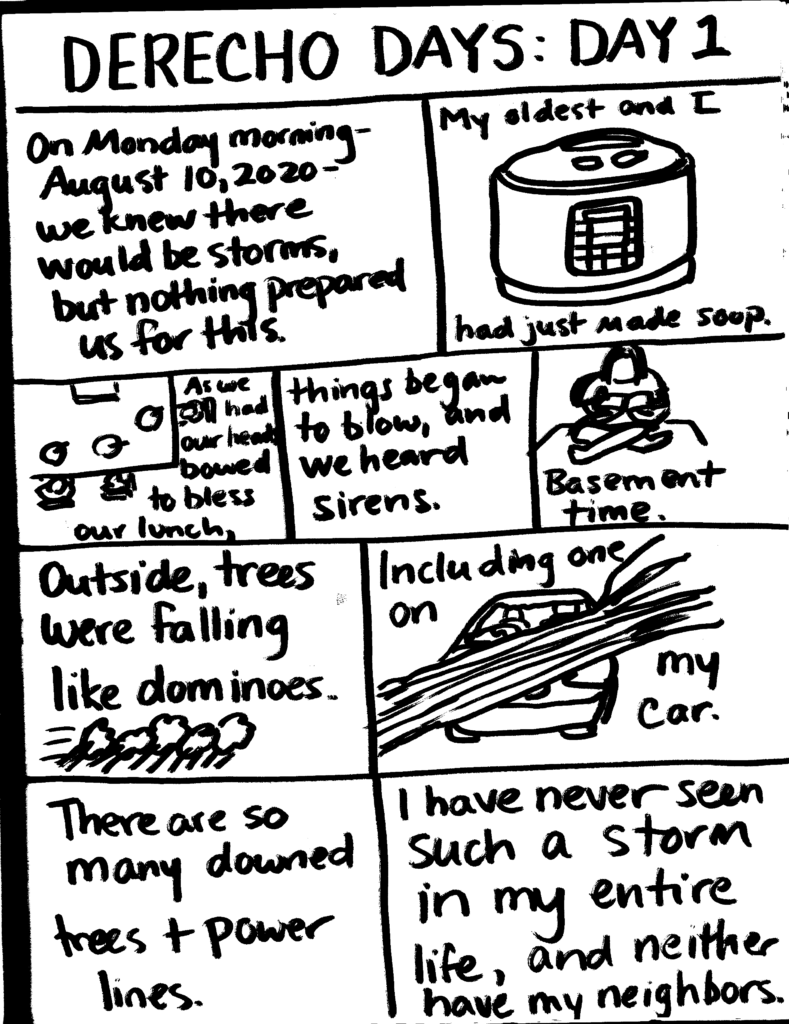

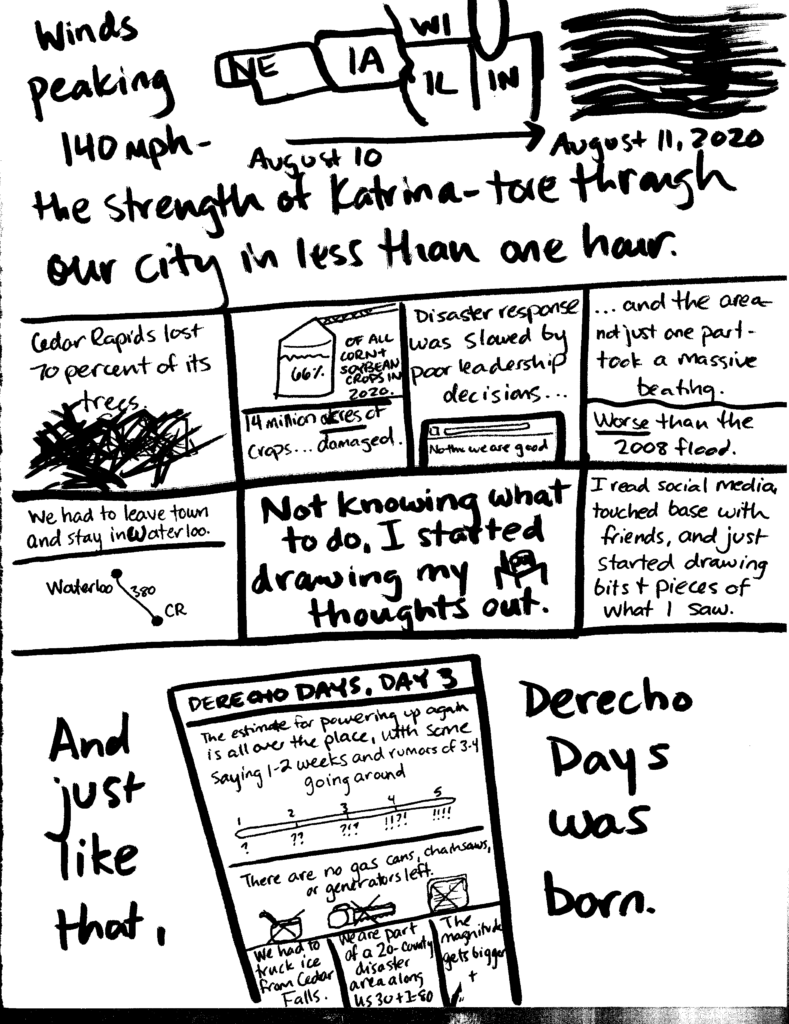

Derecho Days is an experimental, personal comic art piece that navigates the aftermath of enduring the August 2020 derecho: an inland hurricane that, in 14 hours, led to $11 billion in damage, caused 25 tornadoes from Nebraska to Ohio, and destroyed 70 percent of the tree canopy in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Derecho Days is an experimental, personal comic art piece that navigates the aftermath of enduring the August 2020 derecho: an inland hurricane that, in 14 hours, led to $11 billion in damage, caused 25 tornadoes from Nebraska to Ohio, and destroyed 70 percent of the tree canopy in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Derecho Days, a 30-day, once-daily task taken on as part of an online sketch project, Live & Active Culture, consisted of a spontaneous, improvised expression of the day’s events to serve the following roles:

- To share the recovery and relief process with a wider audience, most of whom lived outside the disaster area;

- To celebrate the efforts of those who worked to return the disaster area to a more stable (albeit wildly different) condition for living;

- To navigate the personal trauma of being a disaster survivor by documenting its large-scale and small-scale phenomena for others.

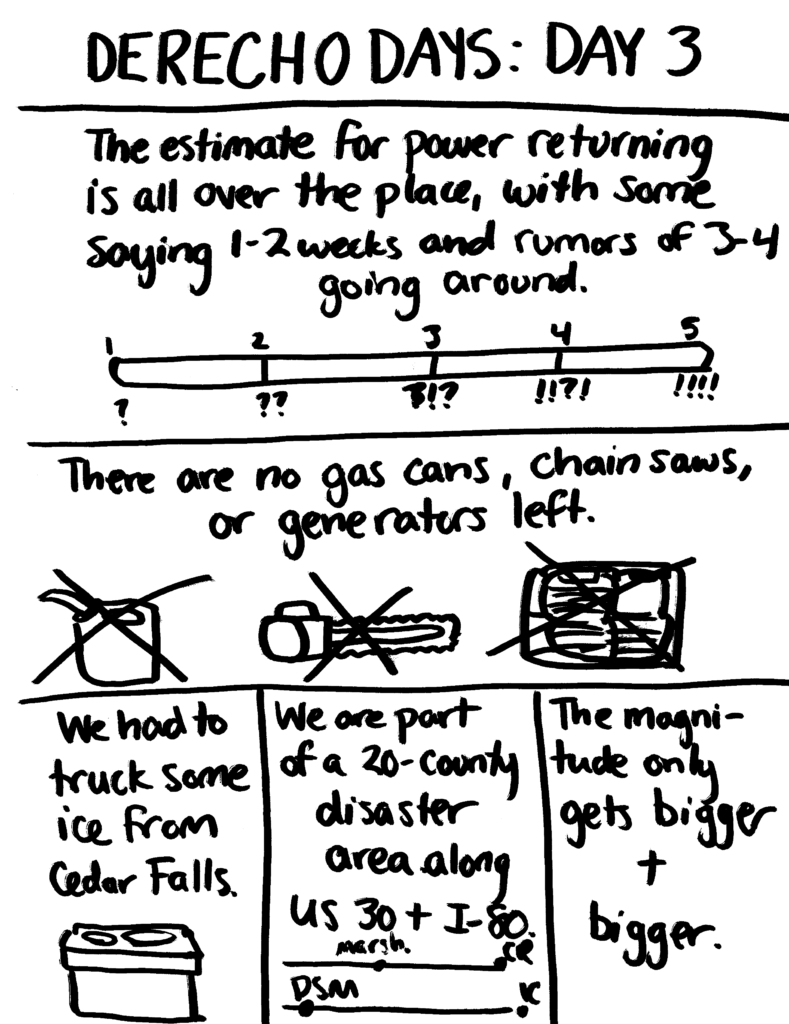

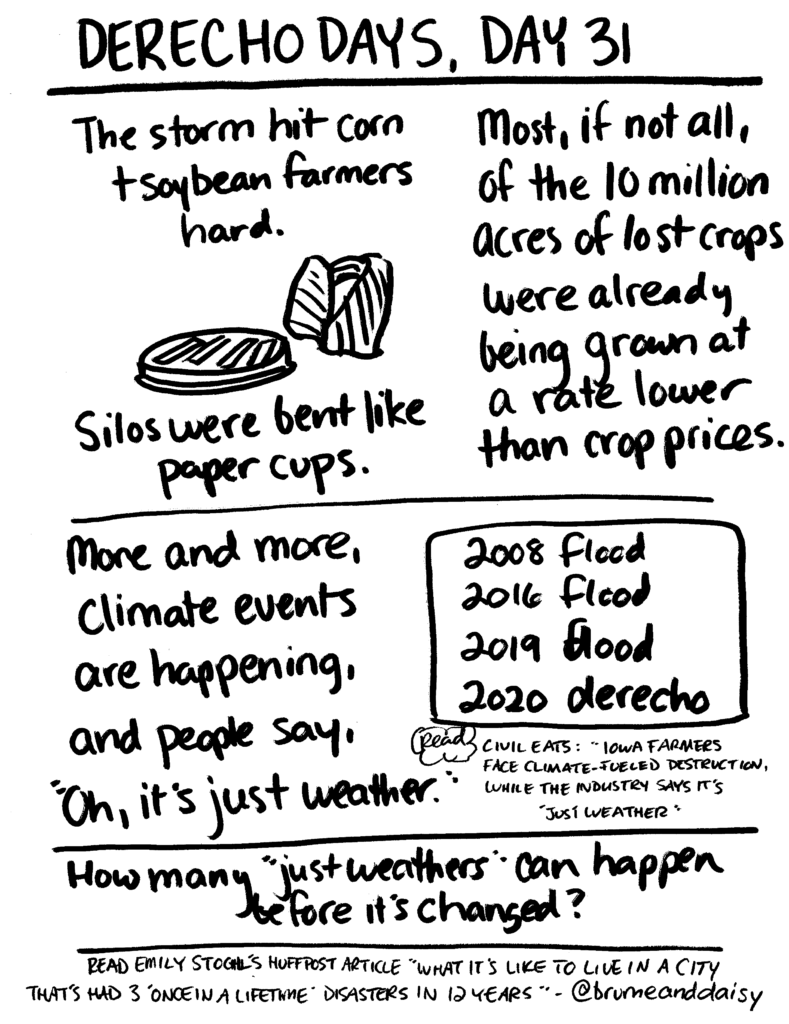

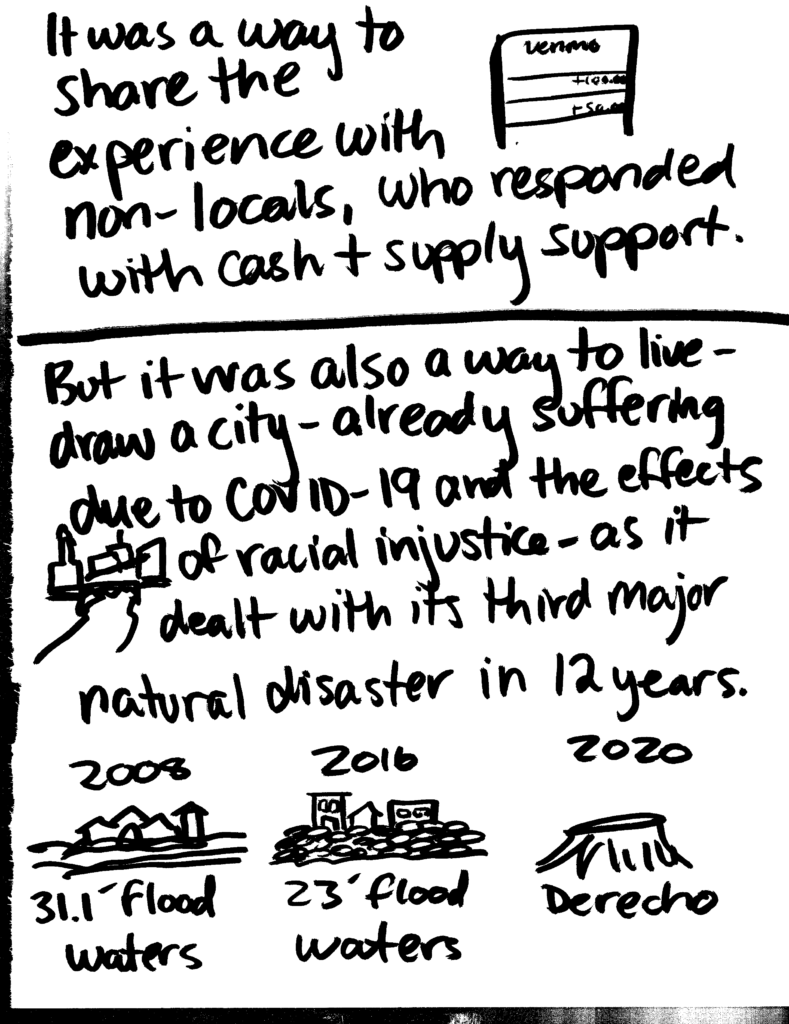

The first part of the series was constructed outside the disaster area, as family medical needs required our family to leave Iowa to stay with family in Indiana. Being away from home (and, at the time, laid off because of pandemic cuts in the cultural sector), the project served as a way to process the experience creatively. Upon returning to the Cedar Rapids area, it became a fieldwork experience, documenting relief efforts, the process of restoring power and utilities to the area, and the emotions that many faced. This disaster was intensified by the fact that Cedar Rapidians had endured two previous floods (2008 and 2016) in the 12 years preceding the derecho.

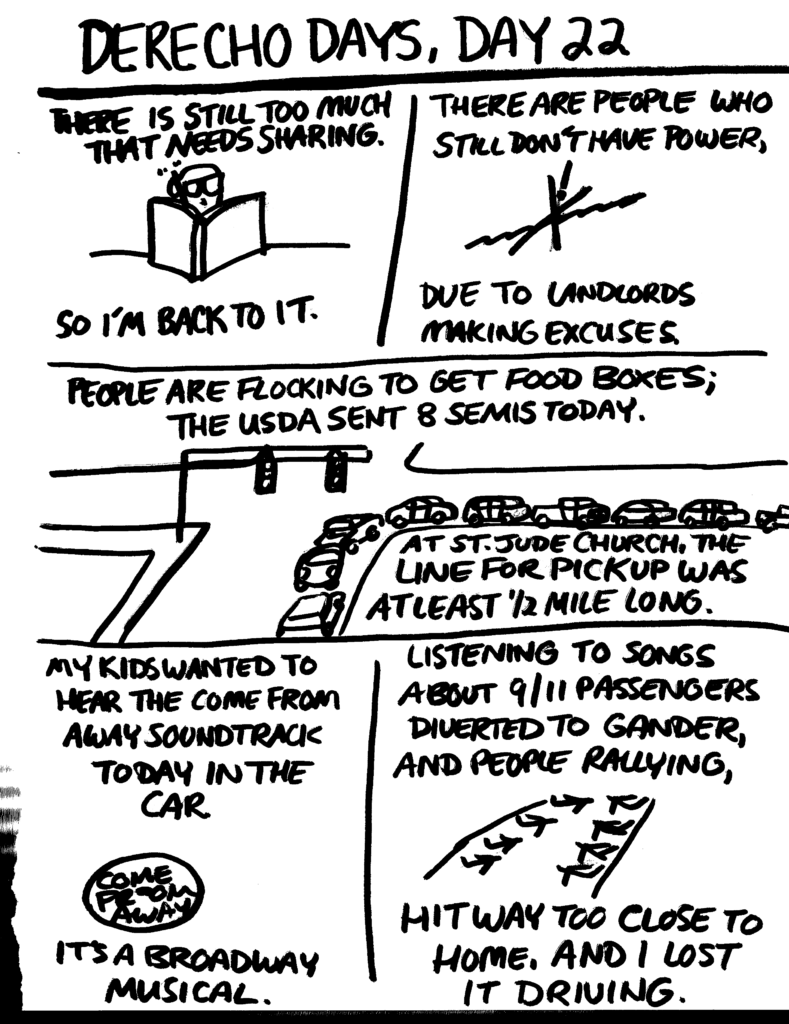

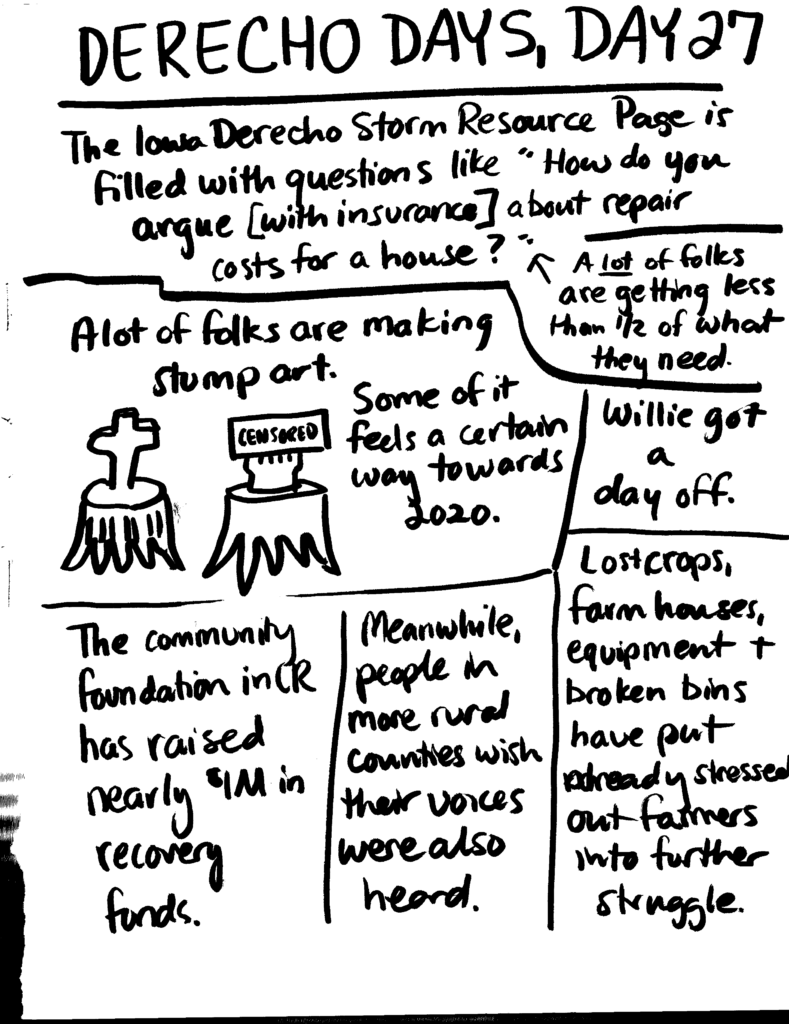

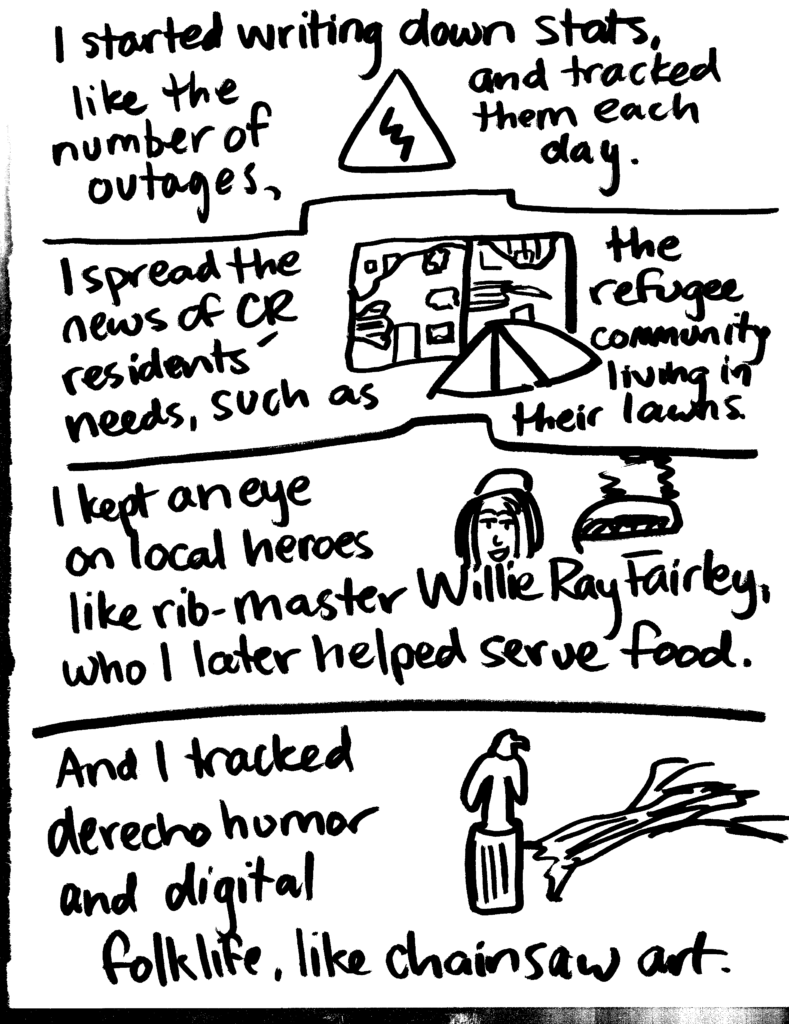

The second part dealt with the community response to the disaster and how people were working to assist others, especially those who lacked access to the same level of resources as the majority of the community. This is where derecho folklife emerges, where local heroes come into play, and where the culture around the disaster begins to materialize.

The final part deals with the gradual fade-out of disaster relief from outside communities, the emotions left behind with the damage, and the things that Cedar Rapidians (and members of the surrounding communities) faced.

As a pedagogical tool, this series offers learners of all ages opportunities to draw from a wide variety of experiences in constructing their own creative project; to learn how to balance the personal and communal in a limited spatial setting; and to use existing skills, as they are, as a foundation for community storytelling.

Day-by-Day Sketch Journal, Selected Panels Find the full set of panels at https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/One-Month-of-Derecho-Days.pdf.

Classroom Connections: Questions for Sketching Disaster

In using this series of panels, educators at any level can choose from the following questions:

How do you think comics can help tell stories of loss and disaster, like that of a storm, earthquake, or flood? What do they help people understand?

How are community members discussed in this piece? How can art highlight the stories of others who may not be in a position to share their stories?

What is the role of outside help in dealing with this disaster? What are the advantages and disadvantages of getting help from outside your group or community?

How does the Internet play a role in helping people in the community find support?

Who do you turn to in times of trouble and struggle in your community?

What kinds of things are being focused on, or talked about, a lot in the comic panels? Who do you think is missing from this story? How would you talk about a disaster like this if this happened to you?

What would happen if you didn’t have as much time to sketch this? How would you share your stories of survival and endurance with others?

Panels like this are also a way to introduce the notion of trauma, including how disasters constitute trauma; the differences between personal and collective trauma; and how trauma is experienced differently depending on one’s personal community, cultural connections, and experiences. In preparing to teach content like this in the classroom, teachers should personally reflect on the following questions:

What do you think of when you think of the word “trauma”?

How is a natural disaster a form of trauma?

What sorts of factors play a role in how people understand trauma?

This is a sensitive matter. Many students personally experience trauma. To minimize impact on students, speak generally and do not mandate students to provide any personal experiences.

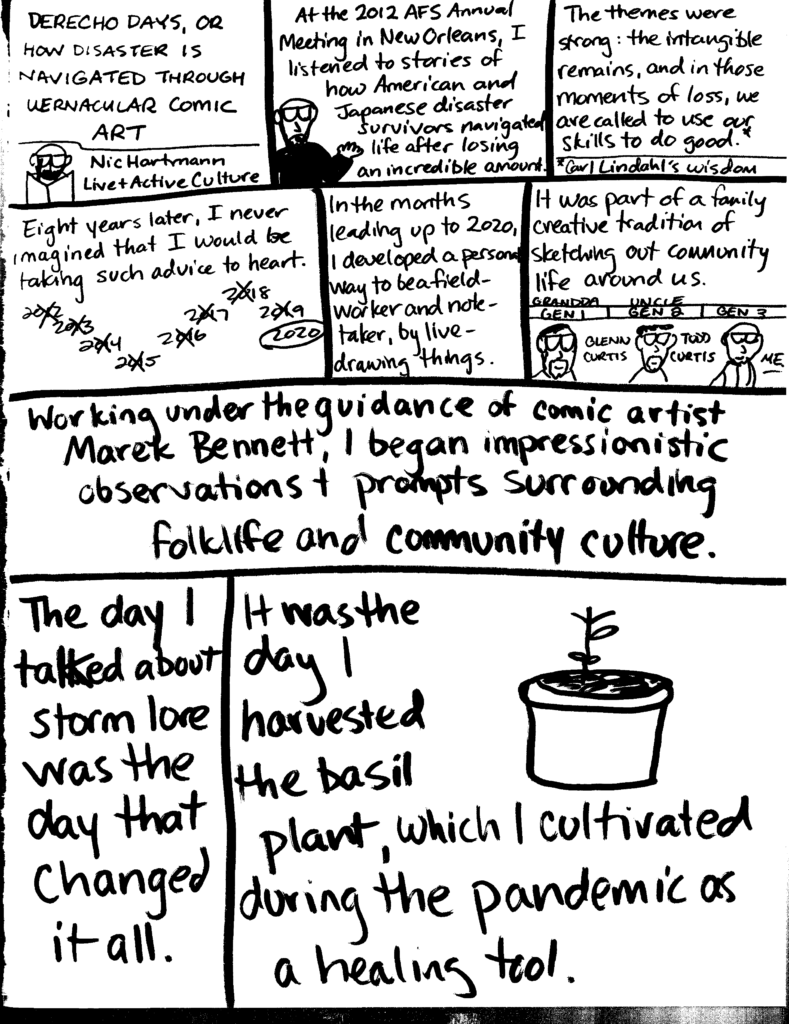

Revisiting Disaster on Ink and Paper: The Making of Derecho Days

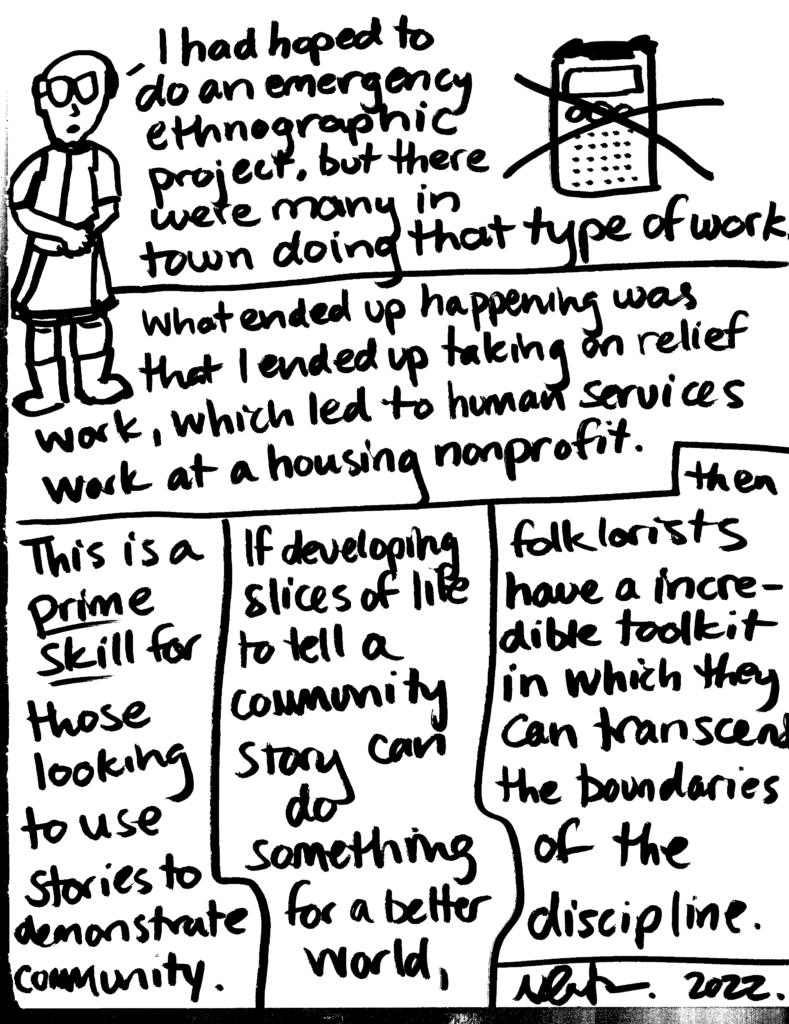

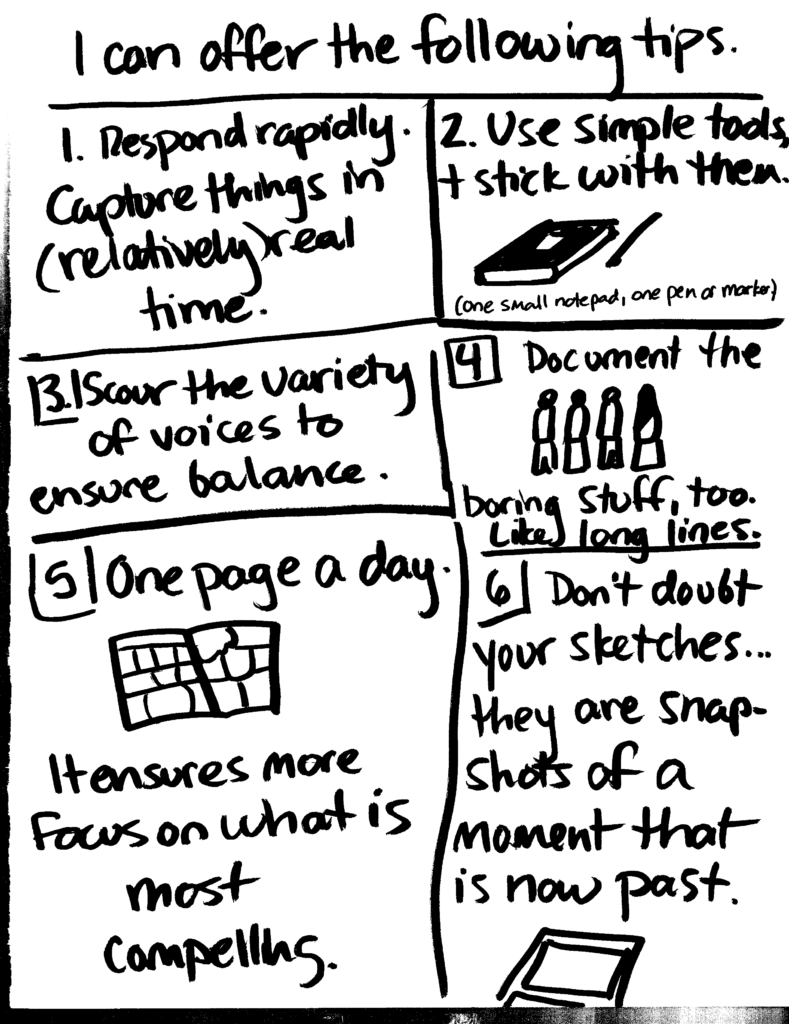

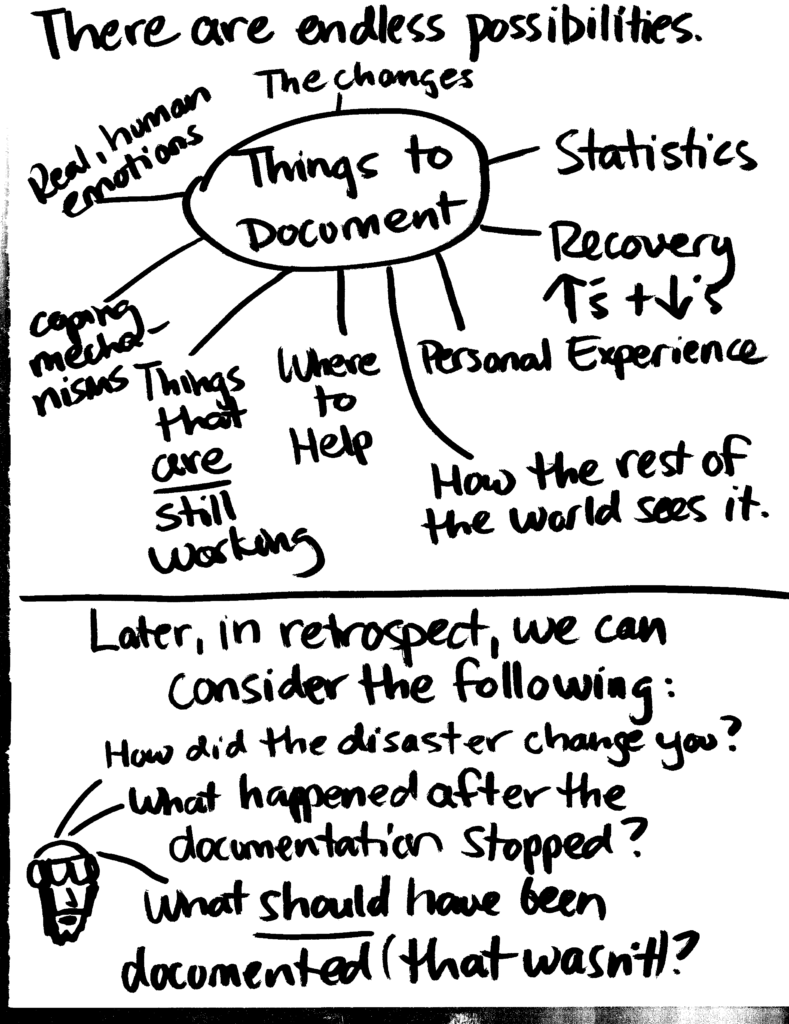

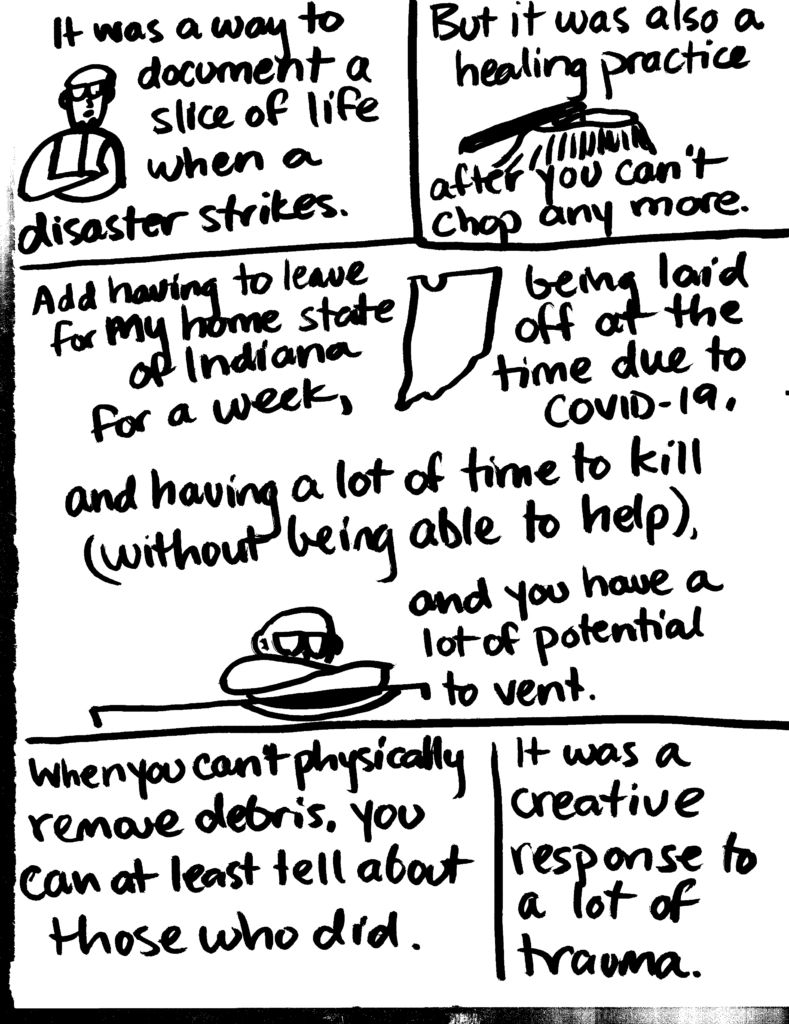

Nearly two years after the 2020 derecho, I constructed a second series of panels about the process of drawing out Derecho Days to look back constructively at the following ideas:

- How personal folk tradition shapes people’s expression of their disaster experience;

- How each account is community-shaped, but individually expressed;

- How engaging in such forms of storytelling has both short-term and long-term effects on the creator.

Classroom Connections: Discussion Questions for The Making of Derecho Days

For students who may be looking at disaster documentation, and its long-term effects, educators may consider the following questions in a classroom setting:

What types of things are still talked about, even two years later? What things are omitted, or de-emphasized? How would you go about asking someone about what they chose to focus on?

How does the creator discuss their personal style? If you were given the duty of documenting a disaster, how might you prepare for interviewing, documenting and sharing your work in a respectful manner?

What kinds of skills does this type of work require?

How do you think you might build relationships with others through drawing and documenting events like natural disasters?

What types of creative projects could you create using field notes or comics? What type of project would you do with the skills you have?

Comic Art and Visual Journaling Resources

- Lynda Barry’s books Syllabusand What It Is include lesson plans, methods, and activities for finding and using a creative voice.

- Marek Bennett, Andy Kolovos, Teresa Mares, and Julia Grand Doucet’s The Most Costly Journey is a graphic novel featuring stories of migrant farmworkers in Vermont, https://www.vermontfolklifecenter.org/elviajemascaro.

- Sally Campbell Galman’s Shane the Lone Ethnographeris a comic-book introduction to ethnography, the core methodology for folklore in education as well as anthropology and other social science courses.

- Julie Pearson-Little Thunder, Johnnie Diacon, and Jerry Bennett wrote Chilocco Indian School: A Generational Story, a graphic novel for educational use published by the Chilocco History Project, https://shareok.org/handle/11244/335900. Find a Project Based Learning module by Lisa Lynn Brooks at https://chilocco.library.okstate.edu/pbl.

Nic Hartmann is Director of Donor Relations for Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa and Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iowa, where he teaches courses in the Museum Studies Certificate program. A folklorist, writer, and third-generation comic artist, Nic’s research and practice interests include occupational folklife, museum education, and folklife as a tool for nonprofit leadership. ORCID 0000-0002-0104-1838