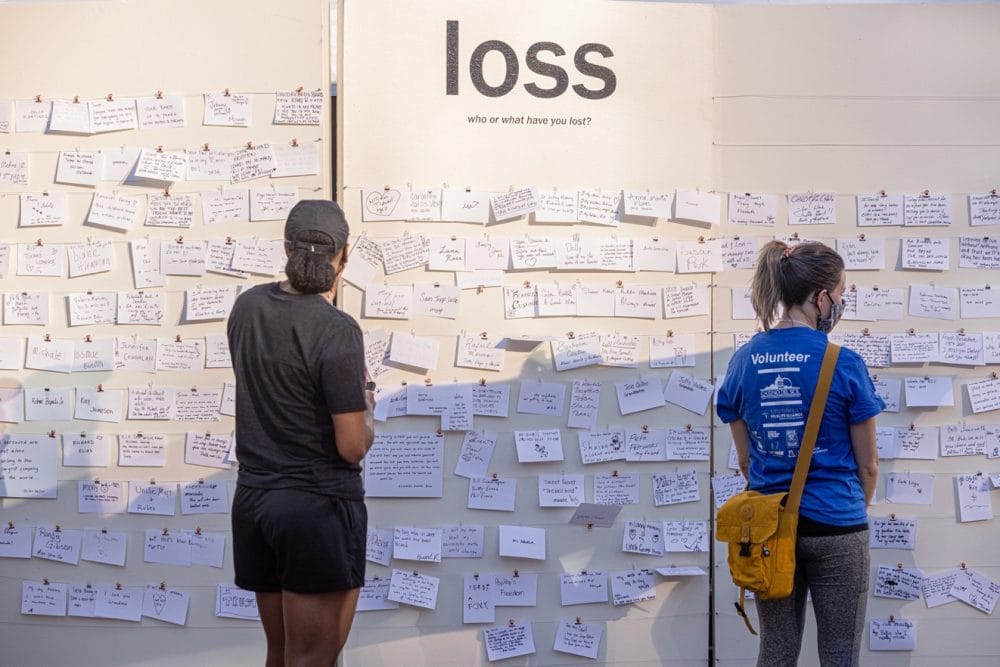

“Wall of Loss” in the Loss and Remembrance Tent at Tucson Meet Yourself 2021. Photo by Steven Meckler.

Not long before Covid-19 reached the Southwestern United States, I listened to a podcast interview with the Nigerian writer and spiritualist Bayo Akomolafe in which he spoke of grieving as ceremony, “…when we grieve, it’s not instrumental to anything but, it’s an opening1…” Too often we are rushed through it, he went on to say, told to hurry up and get back in the game. “We don’t know how to stay in the indeterminacy and the slowness of the compost.”

As someone who cries easily, I was struck by this, reminded of how I’m quick to hide my tears when grief comes. Can I cry in a café? Can I cry in the middle of a work meeting? Where is it okay to grieve openly? Who makes the rules about this? Culture? Tradition? Propriety? Capitalism? How might we change those rules?

“What if there’s a place of just sitting with the trouble of noticing that the things we’ve lost may never come back to us? What if there’s a place of just doing that?” Akomolafe asks. “What if that was an objective of UNESCO, to gather people together and to just grieve?”

I thought of Akomolafe’s questions many times as the tidal waves of Covid-19 brought loss after loss, grief upon grief. I thought of it again in the summer of 2021, as my colleagues at the Southwest Folklife Alliance and I initiated planning for the 48th Annual Tucson Meet Yourself (TMY) Folklife Festival in downtown Tucson in October. As a folklorist and artist, I wanted to make sure we created a space to acknowledge that grief.

Founded in 1974 by the late James “Big Jim” Griffith, TMY is a three-day annual event showcasing food, music, dance, and folk arts from the many folk traditions, ethnicities, and cultural heritages present in Southern Arizona. It’s often lauded for its diverse participants and its diverse audiences, a place where people from different backgrounds can learn about one another’s traditions, finding distinction, overlap, and respect. For years, as an attendee, I described it as the only place you could stand in line for churros or kielbasa or takoyaki and rub elbows with a Chicano lowrider, a Tohono O’odham grandmother, a Buddhist monk, and a Polish folk dancer.

That elbow rubbing didn’t happen in 2020 because of the pandemic, when we moved the festival online, producing a month-long event of virtual programs and performances and hosting a handful of in-person, pop-up, food-to-go events. But in 2021, when it was deemed safe enough to begin to gather in outdoor space, we decided to bring the festival back to the public square.

But would we carry on with the festival as usual? Amid all the grief?

Well, yes. Because people needed to gather again. And “because community and culture are resilient,” as our tagline that year would say. After all, what are the stories of folk, Indigenous, and immigrant cultures if not stories about continuation, about keeping culture alive against all odds through food, music, dance, handicrafts? This is the festival’s beating heart. But what about its fragile, mourning heart?

TMY has long been a place where folklife expressions—quotidian, familiar, and often overlooked—can be seen, heard, and tasted. Traditions and expressions of who we are and where we come from go on public display, shared with pride and delight. I wondered about the grief people would surely be carrying around as they listened to corridos, songs from the popular musical genre of Mexico’s oral tradition; stood in line for Greek spanakopita, Sonoran-style raspados, Egyptian masri, and pad thai; or watched African American girls dance their step traditions on a wooden stage.

Could there be a space for all that grief, too?

Yes. Because no matter the culture we claim, we all know the weight of loss. Our rituals of mourning are as varied as our rituals for celebrating.

We created the Loss and Remembrance Tent, a space within the festival to acknowledge the losses, to bring visibility to the act of mourning, to gather people together, to just grieve.

Building on History and Context

Our idea was not without precedent. Tucson itself is a city that makes space for mourning. Mexican and Mexican American residents have long observed Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, on November 1 and 2, a tradition of honoring and remembering the departed by cleaning and decorating gravesites. Mexican bakeries make and sell pan de muerto, a special sweet bread, and people set up altars in private homes, public offices, and businesses to remember those who have passed on. The region’s Indigenous communities, the Tohono O’odham and the Yaqui/Yoeme people, mark the holiday by preparing foods and feasts for the dead.

The annual All Souls Procession, initiated in 1990 by a local artist mourning her father and now produced by the nonprofit organization Many Mouths One Stomach, brings thousands of people together in Tucson to celebrate life and death in a public grief ritual. Although not intended as a Día de los Muertos celebration, many in the community bring the aesthetic of that holiday to the procession, and myriad other cultural and personal expressions of grief and mourning are represented at the event.

Public displays of grief have also been a part of past TMY festivals. For nearly a decade, TMY maintained a partnership with the Southern Arizona AIDS Foundation (SAAF), which held its annual AIDS Walk on the last morning of the festival weekend. The walk culminated on the festival grounds, where walkers could take advantage of festival infrastructure such as portable toliets and water. In collaboration with SAAF, TMY then created opportunities for festival goers to learn about the lore of the ongoing AIDS epidemic. A display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt created a space for remembering and mourning amidst the festival activities.

More recently, in 2019, the festival brought Ofelia Esparza (a 2018 National Endowment of the Arts National Heritage Fellow) and her daughter, Rosanna Esparza Ahrens, both celebrated altar makers from East Los Angeles, through a partnership with the Alliance for California Traditional Arts. The women built a public altar in an indoor space adjacent to the festival grounds, where visitors could witness and add photocopies of photographs of loved ones and handmade paper flowers, created with the help of Yaqui/Yoeme artist Irene Sanchez. Over three days, the hall was imbued with reverence, memory, and homage, as visitors learned about the role of altars in personal and public life.

From the Editors: Read Ofelia Esparza’s article in this issue about her tradition of altar making.

The Loss and Remembrance Tent evoked the Sonoran Desert landscape and offered a “sacred pause” for visitors. Photo by Steven Meckler.

The Desert Holds Miles of Grief

Unlike previous spaces for grief at the festival, the Loss and Remembrance Tent was purposeful in its neutrality. Rather than celebrating any specific cultural tradition or marking a particular grief expression, it provided a nondenominational space for multiple expressions. This felt important given the multitude of losses in 2020 and 2021—Covid-19, police brutality, racial violence, climate chaos, and more.

For conceptual inspiration, we looked to the Sonoran Desert, where decay and death are both beautiful and regenerative. When death comes to the saguaro cactus—the iconic species of the region—it falls to the dry desert floor, where it nourishes the soil with water stored in its body and the process of its decay. Those nutrients fertilize soil in which young mesquite or palo verde trees can establish and grow into “nurse trees” that protect young saguaros from frost and heat. This cycle shows us how death, while difficult, is a natural, necessary part of being alive and sharing a planet with others.

Processes of decay and transformation happen slowly here (except in the case of sudden summer monsoon storms), so bringing a desert aesthetic to the Loss and Remembrance Tent seemed a resonant way of inviting people to pause, slow down, and contemplate their own inner landscapes of grief. We gathered skeletons of saguaro and cholla cacti, elegant “woodsy” structures that once held up the succulent pith and skin of the plants, as well as branches of creosote, a leafy green, fragrant plant with medicinal qualities. We designed the space with a palette of off-white, beige, and sage green to create a sense of respite amid the color and activity of the festival. We used outdoor rugs, beanbags, and round ottoman poufs and we draped fabric and twinkly lights to create a soft, inviting space.

Within this environment, we created a variety of engagement opportunities for the public, all of which intended to offer a “sacred pause” for visitors to remember and feel the impact of their losses.

Writing, Remembering, and Making Visible the Departed

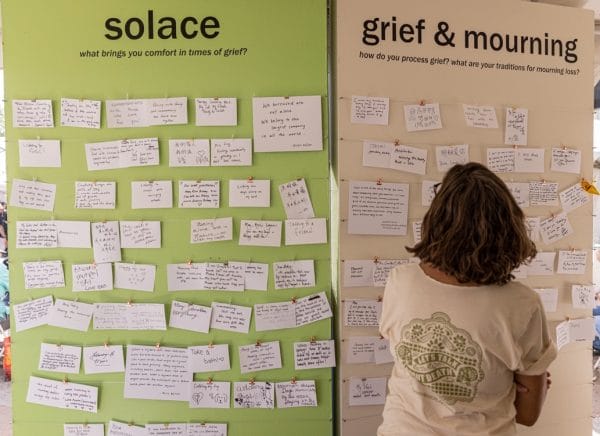

On walls set up throughout the installation, visitors could post written responses to prompts about their practices in grief and mourning and their methods for finding solace.

I tend to my grief with rituals, baths/submerging in H20, asking to be held, building ancestor or dead ones altars, making a box that symbolized my heart and asking those I love to put something inside, lighting candles, writing letters to dead ones.

DANCE.

Listening to music while swinging outside.

Going for a hike alone or with company. Taking the time to be present and listening to life.

Sharing homemade food with chosen family, candle-lit, outdoors, dogs nearby.

Remembering that I’m not the only one who has ever felt this way.

There is no time limit on my grief. Be ever gentle with myself. Comparison never helps.

Bookstores.

Visitors shared traditions and practices of grief, mourning, and solace in the tent. Photo by Steven Meckler.

A Wall of Loss gathered names of those lost and by the end of the weekend, over 1,000 names were displayed. The visual impact of the wall often stopped festivalgoers enroute to food booths and live performances in their tracks, as they paused to take in the names. Those who chose to add to the wall could sit with their grief for a bit longer, as they wrote down the name of a lost loved one. Still others chose to stay to listen to music, relax on the beanbags, or speak with end-of-life doulas, professionals trained in compassionate listening and grief support.

Deron Lopez and Gertie Lopez of the Tohono O’odham Nation shared traditional waila music and spiritual songs of mourning and remembrance. Photo by Steven Meckler.

Sounds for Healing

More than 40 performing acts appeared on festival stages over its three days in 2021. Some were local school groups or affinity clubs, others were professional artists who tour nationally or internationally. We extended an additional invitation to these performers to participate in the Loss and Remembrance Tent. Ten groups accepted, including a group of Aztec ceremonial dancers, a trio of traditional musicians from Bulgaria, a Jewish folk singer, a Korean dancer, and a seven-member group playing Andean music. These artists offered 30-minute sessions of music, song, sound, or dance related to mourning or healing.

Visitors timed their arrival at the tent to listen to these acts or simply came upon them while wandering by. Some returned multiple times throughout the weekend just to hang out and listen. Music from other cultures or sung in languages other than their own allowed visitors to tap into a collective, universal feeling of connection with their individual sorrow. As guest folklorist Virginia Grise wrote in her commentary about the festival at large, “I … let Ludo Djore [the Bulgarian trio] carry me and I wept underneath my big sunglasses, just wept. At that moment, I wish I understood more about this music, why the Bulgarians broke my heart open, how a tradition, a culture, a language you don’t even understand can have that effect on you.”

In addition to live music, a Saudade Jukebox (from the Portuguese word “saudade,” meaning longing, nostalgia, or the love that remains after someone is gone or an experience is over) provided an iPad linked to a Spotify playlist to which visitors could add songs to commemorate beloveds. The playlist link was also shared on the TMY Facebook page so people could add songs if they couldn’t attend the festival. Throughout the weekend, the tent filled with sounds from live musicians or with jukebox remembrance dedications, from The Beatles’ “P.S. I Love You” to Rocio Durcál’s “Amor Eterno” to Bette Midler’s “The Rose.”

One afternoon, five children came into the tent and right away began flinging themselves onto the beanbags, laughing at one another’s tricks. Eventually they settled in and got quiet. When I asked if they knew anyone who had recently died, one girl looked at me and nodded. “My mom,” she said. “Do you want to write her name on the wall?” I asked. She did. Then I showed her the jukebox. “Do you have a song that makes you think of her? We could play it.” She did. Jason Aldean’s “She’s Country.” As the song played, the girl’s grandmother turned to me and said, “It was a particularly hard morning for her. She was really missing her mom.” The girl swung her body back and forth to the electric guitar licks, singing along.

Tucson End-of-Life Doulas offered comfort and resources to festival-goers. Photo by Steven Meckler.

One-on-One Support

Given the trauma that can arise when revisiting grief and loss, we invited end-of-life doulas to be on site for support. Death doulas, or death midwives as these professionals are sometimes called, provide spiritual and psychological support during dying and grieving processes and can assist with practical matters at the end of life such as creating death plans, planning memorial services, and helping families navigate complex financial and legal matters.

As visitors approached the tent, volunteers greeted them, instructing them on the activities and offerings inside and inviting them to contribute to the Wall of Loss. Some visitors would linger, clearly wanting more. While some volunteers in the tent came with specific training as counselors, many self-selected based on their own experience with grief and a strong sense of compassion for others. Those of us present in the tent learned to pay attention, reading body language to sense when people might be carrying heavy grief, inviting them to speak with a doula. Throughout the weekend, the doulas sat with hundreds of visitors, listening, offering compassionate support, and sharing resources.

A display of healing plants of the Sonoran Desert. Photo by Steven Meckler.

Plant Medicine

We also invited a desert herbalist to create a display of healing desert plants for the tent. As visitors viewed the exhibit, the herbalist explained the healing properties of plants like gobernadora (creosote), estafiate (Western mugwort), and gordolobo (cudweed). When she sensed someone with a particular need for healing, she offered them a sprig of estafiate, known for its powerful grounding properties.

One evening, as we were closing the tent for the day, a woman arrived, her shoulders rounding over her chest in the kind of physical manifestation of sorrow we had come to recognize. The death doulas were long gone, but one remaining volunteer, a bereavement counselor, sat with the woman for over 30 minutes letting her cry and share her story, as the rest of us tucked in the displays, packed away materials. Before she departed, the woman came to look at the healing plants display. I offered her a sprig of estafiate, as I’d watched the herbalist do earlier in the day. “I lost a family member to homicide,” the woman told me. “I didn’t know how much I needed this. Thank you. Thank you.” The next day she returned and sat in one of the beanbag chairs for several hours listening to music.

A Place to Feel

Although the design elements and activities of the Loss and Remembrance Tent were important, in the end what may have mattered most was simply creating a place amid the festival to hold individual and collective trauma for a little while—a place where grief was allowed to speak, sing, be seen and heard and felt. A place deeply needed, it seemed.

[The Loss and Remembrance Tent] was highly inspiring and a source of comfort.

You did the community a huge service by having that tent, by moving something that can feel so isolating into the public sphere.

I thought a lot of our loved ones, and with all the other people there, I acknowledged that we are all not alone in losing loved ones. People’s presence was healing.

Thank you so much for creating a sacred, intimate space for the Loss & Remembrance Tent! It was one of the highlights of TMY for me.

Sometimes mourning needs an invitation. A song played through a makeshift jukebox or sung in a language you’ve never heard before. A name written on an index card and hung on a wall. A comfortable place to sit and move through the waves of sorrow, while the world moves along.

Calpulli Tonanztin, a group of Aztec Chichimeca Dancers offered a ritual in the space. Photo by Kimi Eisele.

Over the last decade, the Southwest Folklife Alliance has engaged the public in various programs to help expand our understanding of cultural practices at the end of life. Through our participation with the Arizona End of Life Care Partnership, we’ve sponsored lectures with end-of-life specialists, held mealtime conversations in diverse cultural communities with death and dying experts, created documentary films about end-of-life practices within specific cultural traditions, and worked with ethnographers to document end-of-life rituals, beliefs, practices, and caregiving.

This work has brought a folklife lens to the end-of-life field and has helped, we believe, demystify the processes of death and dying, creating space for important conversations, cultural acknowledgements, and practices that expand respect for diverse cultural traditions and beliefs. But the Loss and Remembrance Tent gave participants a place to feel what they were feeling, to recognize the reality of loss through their own visceral experience, to acknowledge and make space for the weight of what they were already carrying around.

And this is precisely the goal of an event that celebrates and teaches folklife: to offer up a place where we can identify, name, feel, make visible, and share with others the full range life experiences that make us who we are.

Some 2,000 people visited the Loss and Remembrance Tent during the October 2021 TMY festival. I like to think that their time there gave some shape to the indeterminacy of their grief. Not so it could be hurried along to get back to a nonexistent “normal,” but so people could integrate it into their culture, into the colorful and weighty fabric of their daily lives.

Kimi Eisele is a folklorist, writer, and artist. She edits the monthly online journal, BorderLore, with the Southwest Folklife Alliance in Tucson, Arizona. She is co-curator of an exhibit based on the Southwest Folklife Alliance’s work with the Arizona End of Life Partnership, “Walking Each Other Home: Cultural Practices at the End of Life” on display at Arizona State Museum in Tucson September 10, 2022 – Febraury-25, 2023.

Endnotes

- BAYO AKOMOLAFE on Slowing Down in Urgent Times/155. For the Wild. January 22, 2020, https://forthewild.world/listen/bayo-akomolafe-on-slowing-down-in-urgent-times-155.