Screen capture of sample Urban Art Mapping story map. Available at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/4885b98d4fd94be1ac4dd070c9d309cc.

Introduction

The Urban Art Mapping Project at the University of St. Thomas began in the fall of 2018 to document, map, and analyze street art in St. Paul and Minneapolis, MN. Founded by Heather Shirey, Paul Lorah, and David Todd Lawrence–an art historian, a geographer, and a folklorist–the project began in the Midway neighborhood of St. Paul, moving into two adjacent neighborhoods in fall of 2019. From the beginning, we sought to understand how art functions as vernacular discourse in local communities. We understand street art to be a kind of expression, a specialized mode of communication that plays an important role in communal dynamics, particularly in times of unsettlement and crisis. Not surprisingly, when two crises arose in spring of 2020–Covid-19 and the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis–a global proliferation of street art responded to both. In particular, the murder of George Floyd, followed immediately by civil unrest and political uprising, inspired creation of a massive amount of art in the streets, from graffiti writing to Black Lives Matter (BLM) tags to stickers to light projections to large-scale murals. Art was everywhere in public spaces. In response to incidents of violence, cities across the U.S. saw thousands of plywood boards erected on public and private buildings to cover broken windows and to protect intact ones. These boards became canvases for artists to express the emotions and responses of the movement.

Because we were already documenting and mapping street art and conducting ethnographic interviews with artists, community members, and stakeholders, our team was uniquely positioned to document this explosion of artistic expression. In April of 2020 we started the Covid-19 Street Art Database, followed in June by the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art Database. Both databases are crowd-sourced, relying on the public to document digitally and submit street art from the smallest sticker or tag to the largest, most colorful mural. We asked for it all. Through social media, conventional media, and word of mouth, both databases grew over the next year. The Covid-19 database currently has over 700 individual records and the George Floyd database now contains approximately 2,400.

As a multidisciplinary, multigenerational, and multiracial research team, the Urban Art Mapping Project seeks to work in collaboration with and in support of community voices expressing anger, pain, trauma, resistance, solidarity, refusal, hope, and unity through vernacular art in the streets. While street art may be ephemeral and fleeting, it can reveal very immediate responses to world events in a manner that can be raw, direct, and confrontational. These vernacular artistic expressions can help make externally visible what people think, believe, or feel, individually and collectively. In the context of crisis, we argue that street art has the potential to reach a global audience, transform and activate urban space, and foster a sustained critical dialogue.

What follows is an adapted transcript of a presentation that student members of the Urban Art Mapping team shared at the Equity in Action Conference held remotely April 26, 2021. Headlined by Ibram X. Kendi, this conference was organized by the University of St. Thomas to provide a space for community members to engage in conversations around issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion and particularly to engage the concept of antiracism that is the subject of Kendi’s book, How to Be an Antiracist. The Urban Art Mapping team’s work documenting and digitally archiving street art connected to the civil uprising and sociopolitical movement that followed the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers May 25, 2020, speaks directly to these issues. We believe our work with vernacular artistic communal expression in the streets is activist in nature and provides an important tool for students, educators, and researchers seeking ways to engage with the movement for racial equity that continues to this day.

Our work is fundamentally shaped by our recognition that BIPOC voices and experiences are severely underrepresented in archives and this work of documenting voices and experiences must be done with care—without co-opting their creators’ narratives. Working in collaboration with community members through crowd-sourced documentation, we seek to highlight the expression of as many voices as possible, especially those who have historically been marginalized. We believe that artists working in the streets are seeking to re-center the margins by putting art where it is not “supposed” to be.

Informed by cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s call for the archive to be “not an inert museum of dead works, but a ‘living archive,’ whose construction must be seen as an ongoing, never-completed project” (89-92), our team has understood our work in building the George Floyd and Anti-racist Street Art Database as activist work that can help contribute to dismantling white supremacy.

The team members who speak in this transcript are graduate students, a graduate intern, undergraduate students, and a high school intern. Their insight, vision, and commitment have been invaluable. We believe that this presentation and conversation demonstrate the potential of engaging with the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art Database in research and educational contexts. We hope that more community members, teachers, students, and researchers will find innovative ways to engage with the works that we have documented so far with the help of people all over the world.

Note from the Editors: This is our first publication of a Zoom transcript—a format uniquely situated to illuminate some of the ways we met and made community in 2020. The virtual format may also be recognized as illustrating another Creative Text | Creative Tradition. Similar to interviews published in previous issues, some edits were made for clarity, but many informal, conversational moments remain.

The Urban Art Mapping team (left to right): First row Rachel Weiher, Heather Shirey and Eve Wasylik, David Todd Lawrence. Second row Adem Ojulu, Amber Delgado, Shukrani Nangwala. Third row Olivia Tjokrosetio, Frederica Simmons, and Paul Lorah.

Definitions and Political Framework

Frederica: I’m here to introduce you to my colleagues who are non-faculty members on the Urban Mapping team at the University of St. Thomas We’re going to unpack what we mean when we’re talking about this word “antiracist.” But first, I’d like to take a moment to center and focus on the importance of the BIPOC perspectives and antiracist work. When we say “BIPOC,” we mean “Black, Indigenous, people of color.” This acronym is meant to encompass all people of color, while also particularly centering Black and Indigenous people, often the most oppressed members of the POC community. We are also “Calling In” our audience today. In social justice circles, we often do something that’s called calling out, which usually includes someone publicly pointing out that another person is being oppressive. Calling out serves two primary purposes: It lets that person know that they’re being oppressive and lets others know that that person was being oppressive. By letting others know that this person’s behavior is oppressive and unacceptable, more people are able to hold them accountable. When staying silent about injustice often means being complicit in oppression, calling out lets someone know that what they’re doing won’t be condoned. Calling out aims to get this oppressive person to stop that behavior. “Calling in,” however, seeks to do this with compassion, which is really our goal.

Amber: It’s important to begin with centering on the limitations of antiracism and lay groundwork for how the term hasn’t been as effective as it could be. To begin to imagine what cultivating an antiracist university means, it’s important to ask the questions: Who created racist universities and, therefore, who is to take on the labor of creating antiracist universities? Often within institutional spaces, there is an unspoken reliance on and expectation for BIPOC to make legible what white supremacy has rendered illegible or plainly not of importance. This unspoken expectation of BIPOC to spell out and pinpoint trauma, historically and in the present moment, creates an imbalance of existence within institutional life. There is an expectation of dual labor for BIPOC to do their own work while also salvaging the institution away from its foundational histories through translating their lived experiences. The summer of 2020 brought us to a specific moment when the performance of institutional solidarity has become incentivized. I struggle with the frequent use of “antiracism,” as it’s often used as an abstract term without a universal understanding of what all the term entails. This abstract term is often understood to be innately positive and aspirational. However, to achieve the changes the term implies, it’s necessary to take account of the structures that perpetuate racism. Our team thinks that a serious call for structures against racism must also center abolition as well.

We would also like to highlight the importance of a citational practice within academic spaces. We recognize that we are in a particularly vulnerable space being students, and our ideas–increasingly so for BIPOC–can be consumed and reappropriated without our permission or consent. Our team values engagement and a citational learning practice where we respect who we learn from, specifically with regard to lived experiences, and we ask that those who attend this presentation do the same.

Social Context and the Urban Art Mapping Project

Adem: Now that we’ve centered our presentation around the political framework that we’re working from, it’s also important that we acknowledge the time that we’re living in. The Twin Cities have stood witness to a year of violence against Black bodies like no other. In the wake of not only George Floyd’s murder on May 2, 2020, but also Dolal Idd on December 30, 2020,1 and Daunte Wright on April 11, 2021,2 people took to the streets to create in words and images a visual record of the movement through protest art. The Urban Art Mapping team allows a diverse range of students to confront the tyranny of institutionalized brutality in the Twin Cities.

Rachel: The Urban Art Mapping Project collects images of street art in response to social inequalities. Our team consists of professors, student researchers, and interns working across disciplines to create a record of stories being told within visual landscapes across both the Twin Cities specifically and the world at large. We believe in collecting, researching, and archiving antiracist street art to dismantle systemic racism. These archived works remain open to the public while functioning as a fluid historical account of a global uprising.

Works range from documenting how pieces have changed, such as this large mural by Peyton Scott Russell in George Floyd Square,3 documented first June 15, 2020; then February 27, 2021; and last, April 11, 2021 (see below).

Peyton Scott Russell’s Icon of a Revolution at George Floyd Square, documented by Heather Shirey, June 15, 2020.

Peyton Scott Russell’s Icon of a Revolution at George Floyd Square, documented by Rachel Weiher February 27, 2021

Peyton Scott Russell’s Icon of a Revolution at George Floyd Square, documented by Rachel Weiher April 11, 2021.

Some hugely impactful graffiti is only understood within the contextualization of George Floyd’s murder, such as this anonymous writing, “Mama,” recorded in St. Paul June 2, 2020.

Unknown, Mama, documented by Heather Shirey, June 2, 2020, University Ave. West, St. Paul.

And lastly, we are documenting reactivated works by Black-led organizations such as Visual Black Justice and Memorialize the Movement. These are pictures that we have documented of the murals being reactivated March 8, 2021, the first day of jury selection for the trial of Derek Chauvin at the Hennepin County Courthouse.

Murals reactivated March 8, 2021, the first day of jury selection for the Derrick Chauvin trial, in front of the Hennepin County Government Center, Minneapolis, documented by Heather Shirey.

Talking a bit about the ethical archiving of public art–documenting while respecting space–is especially applicable when visiting sacred spaces such as George Floyd Square or other sites where BIPOC individuals have been murdered. This means that we’re only taking pictures when necessary, and we are respecting the rules and the space in general.

Documenting while respecting privacy is also important—this includes privacy of homes and of individuals. This is especially relevant when we’re looking at protests and not including any faces that could be further implicated. We see this project as an act of resistance. We are documenting things that the city would maybe rather we not document and keep as a historical archive of what’s happening. And last, continued group discussions and accountability are necessary. We meet weekly or more, if needed, to talk about what we’re doing, why it’s important, and ways that we can better ourselves.

About the Database

Eve: The George Floyd and Anti-racist Street Art database preserves and analyzes street art from around the world combating systemic racism and demanding equality and justice. It uses metadata such as the date of documentation, geolocations, and theme descriptions. It is freely available as a resource for students, educators, activists, and artists. While the project has its roots in the Twin Cities, we are actively collecting submissions from around the world. For example, images of George Floyd, accompanied by the text “I Can’t Breathe” have appeared on walls from Brazil to Syria, as have text and images criticizing the militarization of the police, memorializing names of the countless victims of racially motivated violence, calling for structural change, social justice, and an end to racism.

The ephemeral nature of street art gives it the unique ability to be adapted by artists and community members, changing with new events. A piece entered into the database multiple times can reflect what happened in the world around it. Preserving these reactions and actions gives evidence to parts of history that may be lost with the physical art were it not documented. This is why the date of documentation is so important.

How to submit your image to the Omeka database

When opening the database, find the “contribute an item” button on the top menu navigation. Descriptions of your submission should be detailed but will vary depending on what is being contributed. An entry of a detailed set of plywood boards would need more description and possibly more contextual information than a piece of written BLM graffiti. If the artist’s name isn’t known, you can move on to the next field. The title of your entry doesn’t have to be creative or original, it serves as another description or summary of the entry. When entering the address where your picture was taken, it is very important to follow this order so the entry can be mapped correctly: street address, city, state, and country. When available, enter the contact information of the artist so they may be contacted about the use of their work in the database. Artists are informed about the educational purposes of the database, and their artwork would be removed at any point if its place in the database was against their wishes. This contact information can include social media if known. The url is https://georgefloydstreetart.omeka.net

Spatial Analysis and Highlighting Community Stories

Shukrani: Understanding communities through street art—we’re able to do this by interviewing artists in the community about the work they produce and why they do so.

One artist we interviewed was Seitu Jones about what happened last year during the pandemic and the George Floyd incident. He enacted a social movement by bringing people together to work and produce art. He offered a blue stencil of George Floyd people could download and post it wherever they wanted. You can see in this Instagram post that he gathered a lot of support. In addition to the work that he was trying to support with “Blues for George,” he made a comment that really stood out to me: “One of the tenets of the many different philosophies that I glommed onto in the 60s and 70s…is that you should leave your community more beautiful than you’ve found it—and that’s what I strive for in all of my work, wherever that work is.”

What he said really stuck out to me as an artist as well because it showed why antiracist street art is not only just talking to individuals who don’t agree with you. It’s also about trying to make the communities where you live more livable and highlighting the stories within them.

Screen capture of Instagram posts of #BluesforGeorge stencil in use. Stencil and instructions can be found at https://seitujonesstudio.com/blues4george.

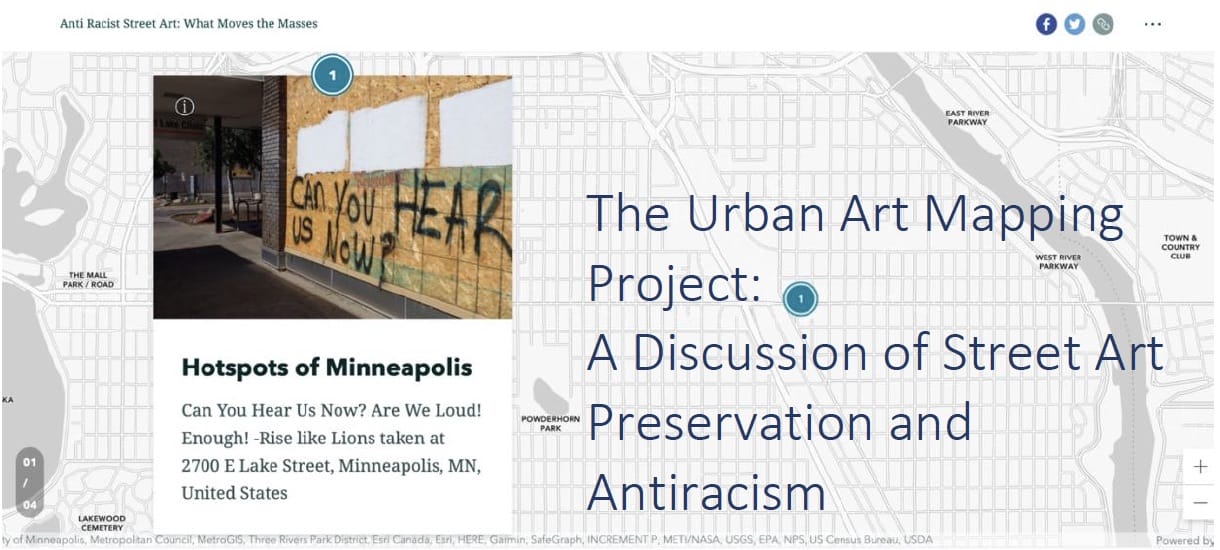

Olivia: I’d like to talk about the impact of story maps and why we use story maps. You can see on the right side there’s a screen grab of a current story map that that my professors and I are working on for the team. Story maps have three main contributions. First, they combine elements and storytelling with interviews and maps as well as images into a cohesive big picture. Second, story maps provide a visual representation of artworks combined with bite-sized information for viewers. And third, they bridge the gap between the academic and the informal and this allows us to engage in discourse.

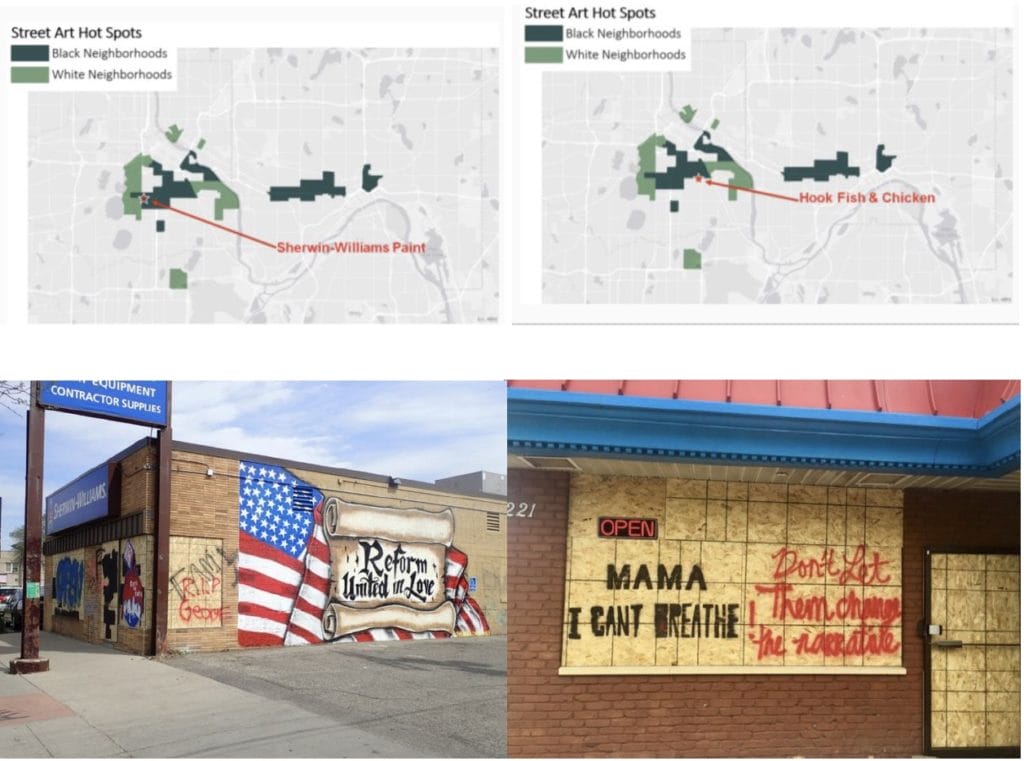

Because our database is so big, it’s difficult to see or connect ideas or variables together, and story maps bring all these interesting nuances with artists and street art together. You can see on the next image an example of qualitative analysis of artwork in Black and white neighborhoods.

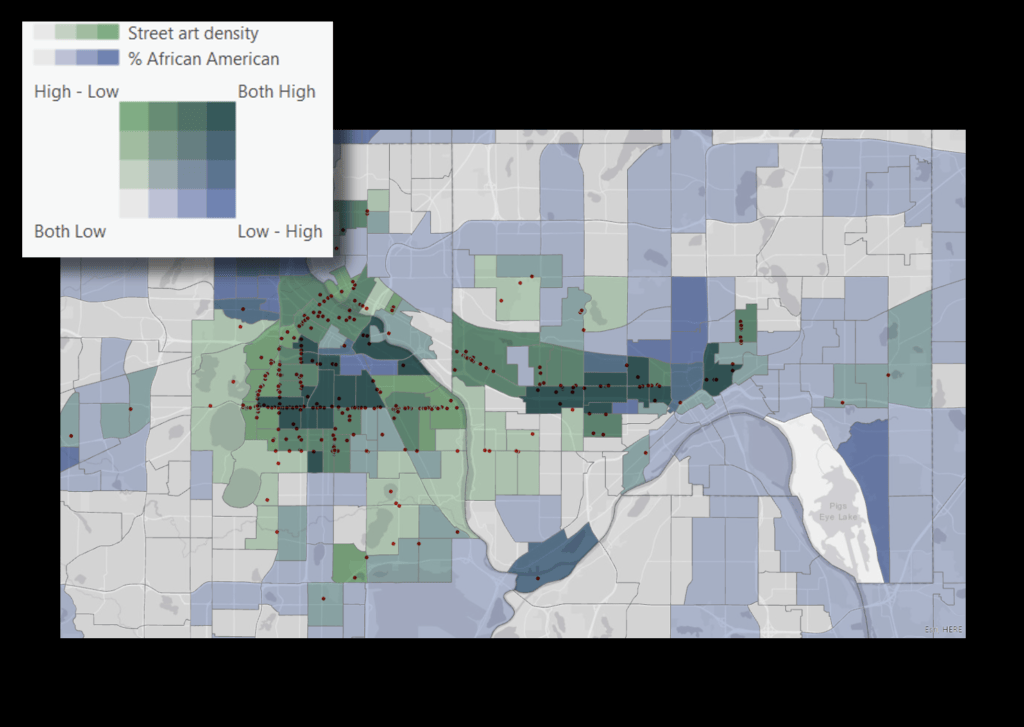

Professor Lorah, one of the faculty directors of our team, created this map. There is a difference in the amount of street art in Black and white neighborhoods. Now, we can analyze this in a way where we look at the amount of street art in these neighborhoods, as well as the type and tone of messages of these artworks in areas of government-centered places and at the epicenter of George Floyd’s death, like 38th and Chicago and at the Hennepin County Government Center where Derek Chauvin’s trial was held.

Map showing street art density and percentage of African American residency by neighborhood in the Twin Cities metro area. Map created by Paul Lorah.

In the next images, we can also see further analysis–pictures that have also been taken from our story map, where hot spots in Black and white neighborhoods differ. In the first picture is the Sherwin-Williams paint store at the border between Black and white neighborhoods. The message says, “reform united in love,” and the second picture underneath a storefront located a Black neighborhood says, “Mama, I can’t breathe,” and “Don’t let them change the narrative.”

We can very clearly see the difference in tone between these two pictures. The first calls for solidarity and unity together, while the second is direct in its call for change.

Sherwin-Williams store on Lake Street in Minneapolis, documented by Froukje Akkerman, June 6, 2020. (L) Hook Fish and Chicken on Lake Street in Minneapolis, documented by Sally Pemberton, July 1, 2020. (R)

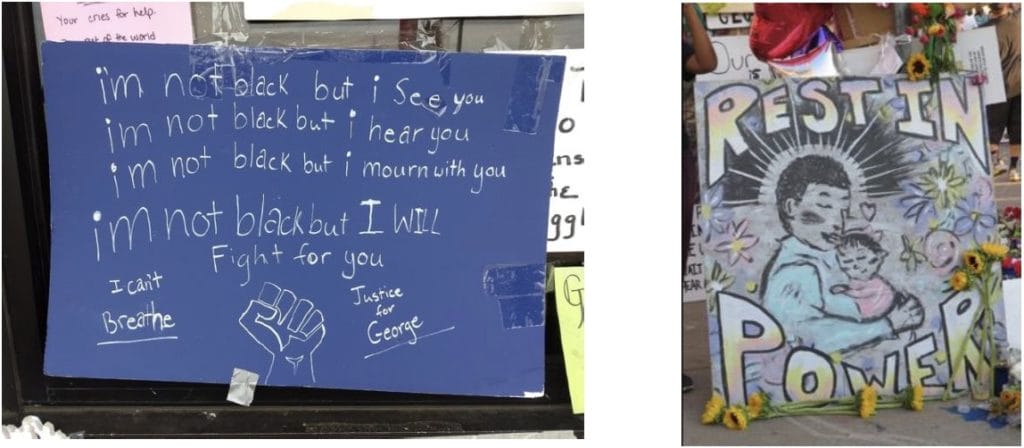

Next, we highlight two pictures documented around George Floyd Square. The messages call for change and also take on a tone that is not passive. There is a need for this kind of intersectional activism and a striving for change. What story maps can do is highlight important individual pieces in the database that allow viewers to engage with those pieces in greater context.

Poster on the south side of Cup Foods at George Floyd Square (L). Documented by Lisa Keith, June 5, 2020. Ana Freeberg (artist), George Floyd-Father, propped against a signpost at George Floyd Square (R). Documented by Sally Pemberton, June 4, 2020.

Shukrani: I can share the trends we noticed in the database. One of the coolest things we are able to see—which is not cool, but sad actually. You can notice the difference in income level between the neighborhoods where you find the art. If you’re in North Minneapolis or uptown, the art is very pretty. It’s very empowering, lots of beautiful colors. If you go to areas like Midway or where it’s less and less income compared to uptown, you begin to see that the messaging and the colors are very gritty. It even tells in a more realistic way what’s going on in that area as opposed to other areas that are not being affected by oppression. These trends continue, and, like Olivia touched upon in her story map, you can even show the dramatic change in messaging across different areas.

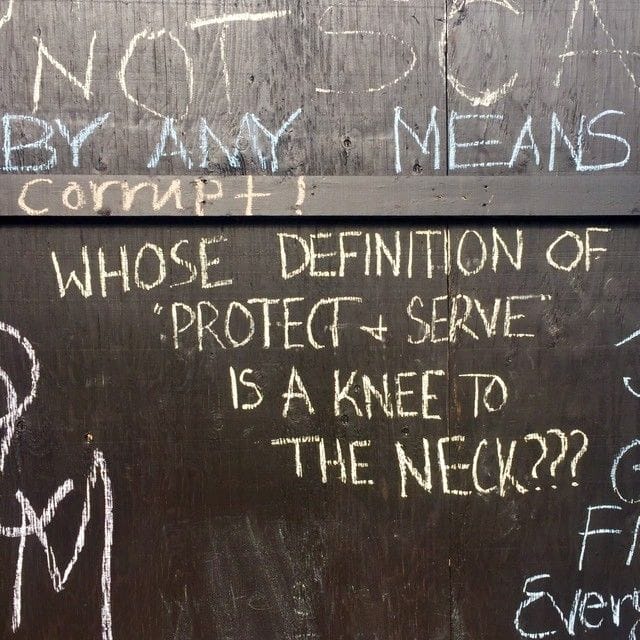

Olivia: Looking through pictures from the database you can really see the differences in the tone of the messages, the emotion that comes through. The important thing to note is the immediate, visceral response that viewers have to these works. It could be as simple as a scrawl on chalkboard, like the one that said “corrupt” with an exclamation point. It was light pink against a black background.

And it was just one word, but it was so impactful. It’s like you could feel all the anger and frustration that this person wrote into the word. I don’t think this is extrapolating. I just feel that when it comes to street art, because it’s so raw, because it’s so emotional, and because it’s so immediate, it is what it is, and there’s no pretense. There’s nothing quote/unquote pretty about it. It’s just out there for you to see, for you to feel, for you to acknowledge. That’s what really stood out to me as we’ve all been documenting these works of art.

Writing in chalk on a barricade outside the Hennepin County Government Center, documented by Sally Pemberton, March 3, 2021.

Community Partnerships and the Importance of Core Values

Frederica: When thinking about how to strive for authenticity when building community partnerships, an issue that often arises in institutions built on a foundation of white supremacy–whether it be implicit or explicit–when attempting to become antiracist, lies in the efforts that follow the initiation of that endeavor. It’s more than fair to say that once an institution has realized that it has been racist, and would now like to become antiracist, it seeks to activate its programing initiatives to fall in line with this goal. This often means that institutions will blindly seek diversity but ultimately fail to attain it. This is most common when it comes to hiring initiatives, but it’s also frequently seen when institutions are governed by their position as public-facing organizations that value the perception of only certain communities. These institutions often maintain the pretense that they are community-facing, which should mean that they not only value community feedback, but that they also exist to serve the entire community. It is easy for institutions, even with the best intentions, however, to fall back into white supremacist tendencies when seeking culturally and racially diverse partnerships, often to the point that they perpetuate further harm instead of bringing forward the positive change that they intend, but again, fail to execute. We, the Urban Art Mapping team, strive to develop authentic partnerships within the community, watering the seeds of connection through our commitment to the work and following the growth wherever it leads.

Urban Art Mapping and Memorialize the Movement teams.

Adem: Our community partner is Memorialize the Movement,4 founded by Leesa Kelly. Memorialize the Movement began during a Minneapolis Global Shapers meeting when Leesa was brainstorming how the group could contribute to the response following the murder of George Floyd last spring and the uprising that followed. It took shape as a grassroots organization with the mission of collecting and preserving plywood artwork created in the wake of that difficult spring. With the help and guidance of the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery and through the partnership with Save the Boards, Memorialize the Movement’s growing team of volunteers around the Twin Cities began to collect many plywood murals from businesses and artists to save and collect as many as possible.

Since July of 2020, they have collected over 750 boards, now stored in a climate-controlled space at the Northrup-King Building, a large arts complex, until they establish a more permanent space. Their long-term plan is to build a public memorial space so that this Black narrative is preserved and accessible to the public. The partnership between the Urban Art Mapping Project and Memorialize the Movement began in January 2021, when the Urban Art Mapping team came out to support them in digitally archiving their boards.

In February 2021, three of us on the graduate team began supporting Leesa more directly on her dream of creating an exhibit (learn more). They’ve been working to showcase all the different works that folks have created within the past year. What’s important to note with this partnership specifically is the organic nature of the collections that we’ve created. Both parties benefit from the work that we’re able to do together. And through this process, we’ve been able to create a strong foundation of trust that will be really important as we continue this work in the future.

We have listed the core values to highlight how they dovetail with the Urban Art Mapping team’s values. Often, we as academics have many ideas that we would like to go ahead and run with but don’t look to the community to see what folks are doing already on the ground. This partnership is a great example in that we’re able to uplift an organization and help embolden their voice rather than speak over them.

We have listed the core values to highlight how they dovetail with the Urban Art Mapping team’s values. Often, we as academics have many ideas that we would like to go ahead and run with but don’t look to the community to see what folks are doing already on the ground. This partnership is a great example in that we’re able to uplift an organization and help embolden their voice rather than speak over them.

Audience Question: I have a question…my family is from up north, and on Facebook I’m getting a lot of, you know, thin blue line–stand with the police, that kind of posts. Have there been those kinds of street art messages almost as a counter to the George Floyd?

Frederica: I’m sure that there are instances of street art supporting that more racist/pro-police stance. In our work, I don’t think that it’s possible for us to have an antiracist society while still having police. Abolition is necessary. Therefore, there are no pro-police related works in the antiracist street art database. That’s not in line with the goals. Although we are encompassing all antiracist street art in this work, it originated with George Floyd and George Floyd was murdered by a police officer who was acting on his duty.

Rachel: We do encounter racist graffiti and murals have been defaced. This recently happened in Minneapolis where offensive language was written over a George Floyd mural. We document those changes. However, we do not publish those racist works, but we make sure that we have that information because that is a part of what’s happening in our nation right now. That’s not what this database publicly archives. We have that information because part of what we look at is change. And change in our work doesn’t necessarily mean something that’s hopeful or positive.

The Personal and Educational Impact of the Database

Audience Question: I’m a St. Thomas alum and live out of state and I’m an art teacher. I’d like to contribute some things. Do I need to contact the artist beforehand, since it’s an actual database? And do I need to research the description of it from the artist’s words?

Frederica: We don’t require anyone submitting a piece to the database to have secured the artist’s permission or approval themselves. There are a couple of reasons for this. Often what you’ll see if you go through the database are a lot of works that are really simple tags that aren’t a whole elaborate mural, but just a brief moment of someone writing something and continuing to move forward. And in that instance, you wouldn’t be able to identify the artist. But the more data, the better. The more exposure we can give these artists, the better. So, if you are able to find them, great. We’d love for you to include that, but I don’t want people to feel discouraged from sharing just because they don’t know who created it.

Rachel: We double back and make sure that the archive does support those artists and that we have their permission to include the works. When you submit a work, it is marked as private until we publicly put that out there. We double check information. You do not need to ask an artist to provide a description. We’ve found it’s a great educational tool to have students create their own descriptions. I know that Dr. Shirey has activated this educational tool with other universities and projects to make sure that people are able to create work and create their own labels and their own language and submit that to the database. So, we absolutely encourage you to use that as an educational tool and as a way to engage the community.

Shukrani: I would say another cool thing I have learned from this whole project is how to notice tones and nuances within street art. When it comes to using this database in the classroom, I have experience taking a class that focused on highlighting the stylistic similarities in art pieces and literary pieces from the same era. So, with this database what you could essentially do is compare works in it to news headlines, stories, and social media posts from 2020 to uncover intriguing similarities.

After that, you could guide your students through an individual or collective journey that leads them through a visual and literary timeline that shines light on the tones and nuances found within the stories in the George Floyd movement. This could consist of a timeline with news, art from the database, and stories from various publications reacting to the movement. As a result, your students will finish this experience with an in-depth personal and contextual takeaway of the importance of the movement.

Frederica: We’re working toward putting as much context as possible on all our records. That’s a retroactive endeavor so it’s going to take us quite some time. But, for example, if a work is referencing Breonna Taylor, we want to include in our description a concise but clear explanation of what happened to Breonna. We want to make sure that we are highlighting these stories and including them as part of our narrative. So that’s not just, oh, look at the art, but what is this art talking about?

What has been the personal impact you have experienced as students doing this archival work?

Frederica: I am born and raised in Minneapolis. I am biracial, and from a very young age, my father would express to me that Minnesota was the most racist place that he has ever lived. And as a child, I didn’t understand what that meant… So, I had always been acutely aware that there was a problem, but I have the privilege of being light skinned, and I’ll fully acknowledge that this is absolutely something that protected me from racism for a long time. To know that this racism has always existed here and plagued the people who matter the most to me and have to have the intersection where George Floyd was murdered be so directly close to home shook me to my core in a way that I still can’t fully verbalize. So, for me, this project means being able to preserve a movement that nobody wants to acknowledge and to have the opportunity to share our stories and make them widely accessible… it means the world to me.

Shukrani: This project has been a very eye-opening experience because I’m an international student from Tanzania. Most of us have dark skin color so I’m used to seeing myself everywhere. To come to a country and become the minority was a new experience to me. By coming to this project, I got firsthand experience in the streets, interviewing people and hearing stories that I had not had access to. By gaining all this context, I now have an understanding that there are stories that need to be heard, and there are also forces working to suppress these stories.

Conclusion

This conversation is similar to those our team has been having with students and teachers all across the country and around the world. We always envisioned this project as a collaborative one that relies on the contributions of community partners, organizations, and individuals. The ongoing success of the Urban Art Mapping Project depends on regular everyday people–community members, students, teachers, researchers, and others–seeing art in the streets and responding to the critical discourse that street art offers. It also depends on people’s willingness to take street art seriously and understand it as an important mode of communication and expression. Our project is driven by a recognition of the importance of vernacular expression rooted in community identity, practices, and beliefs. We believe that walls speak and that we all should be listening, paying attention to art in public places that activates space and reveals critical conversations of voices that often go unheard or ignored.

Most importantly, this conversation demonstrates the educational and transformational potential that comes from encouraging students to engage with vernacular art and expression. Members of our team, from our high school intern to our graduate student researchers, have been profoundly affected by this work. In addition to members of our team, we have engaged with students and teachers from high schools and colleges in the Twin Cities and across the nation, inviting them to conduct research using our databases and to help us in our work of documenting and archiving street art. It is our hope that opportunities to share and connect with students and teachers across the country will lead to more people being influenced by the amazing work of street artists, trained and untrained, whose creative texts serve as a critical discourse accompanying an ongoing movement for racial equity and justice.

We further invite readers to join us by being on the lookout for street art including BLM tags, graffiti writing, stickers, spray-painted images, light projections, wheat-paste posters, or murals. Anything painted on, projected, or affixed to the built environment that addresses police violence or antiracism is of interest. If you notice any art in the streets, snap a picture on your phone and upload it to our database at GeorgeFloydstreetart@omeka.net. In documenting this moment, we can all help to memorialize expression that might otherwise be buffed, painted over, or lost to time. Our work is activist, seeking to highlight those voices and not let anyone “change the narrative.”

David Todd Lawrence (he/his) is Associate Professor of English at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, MN, where he teaches African American literature and expressive culture, folklore studies, and cultural studies. He co-directs the Urban Art Mapping Project along with Heather Shirey and Paul Lorah.

Rachel Weiher (she/her) is a graduate student at the University of St. Thomas in the Art History and Museum Studies Department. Previously she received her Masters in Counseling through the University of Minnesota and is passionate about anti-colonial and trauma informed community care in art history.

Frederica Simmons (she/her) is a graduate student pursuing degrees in Art History and Museum Studies at St. Thomas. Her research and praxis center on historical and contemporary BIPOC artists, feminist theory, and challenging the art historical canon.

Adem Ojulu (they/she) is a graduate student in the Art History and Museum Studies department at St. Thomas. They are an abolitionist with an interest in community engagement and public history.

Olivia Tjokrosetio (she/her) is an undergraduate student in the Psychology and Family Studies department at the University of St Thomas. She is interested in understanding the complex racial climate here in the United States and as an international student, seeks to advocate for the BIPOC community.

Heather Shirey (she/her) is Professor of Art History at the University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Her teaching and research focus on race and identity, migrations and diasporas, and street art and its communities. Together with Todd Lawrence and Paul Lorah, she co-directs the Urban Art Mapping Project.

Amber Delgado (they/she) is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota pursuing a Masters Degree in Heritage Studies and Public History. Their research interests include Black feminist theory, gentrification, and the politics of public space.

Paul Lorah (he/his) is an Associate Professor of Geography at the University of Saint Thomas in the department of Earth, Environment and Society. His teaching and research interests range from environmental economics to the geography of street art. He co-directs the Urban Art Mapping Project along with Heather Shirey and Todd Lawrence.

Shukrani Nangwala (he/his) recently graduated from the University of St. Thomas with a Bachelor’s in Marketing and a minor in Data Analytics. His interests include photography, videography and economics.

Eve Wasylik (she/her) is a junior attending high school in St. Paul, and has been a student research collaborator with Urban Art Mapping since November 2020. She is passionate about queer history, theory and musical composition.

Endnotes

1Somali American Dolal Idd, age 23, was killed by Minneapolis police officers at a gas station in South Minneapolis December 3, 2020. According to police, officers stopped Idd in his car and had probable cause to suspect he was in possession of an illegal gun. His killing quickly became a rallying point for protests and vigils at the gas station where the incident occurred. Idd was the first person killed by Minneapolis police following the murder of George Floyd six months earlier. See Yuen, Moini, and Feshir, “Here’s What We Know About the Fatal Shooting Outside a Minneapolis Gas Station,” https://www.mprnews.org/story/2021/01/01/heres-what-we-know-about-the-fatal-police-shooting-outside-a-minneapolis-gas-station.

2 Daunte Wright was killed by Brooklyn Center police officers April 11, 2021. Brooklyn Center is a suburb of Minneapolis about 14 miles north of George Floyd Square (38th St. and Chicago Ave.). Wright was also killed during a traffic stop. While on the phone with his mother during the stop he told her he believed he had been stopped for having an air freshener hanging from his rearview mirror. He was shot by an officer during a struggle in which she claimed to have mistakenly fired her gun instead of her taser. The killing of Daunte Wright was followed by weeks of demonstrations and protests at the site of his killing and at the Brooklyn Center police department building. For more, see: https://www.nytimes.com/article/daunte-wright-death-minnesota.html.

3 George Floyd Square is a spontaneous memorial honoring George Floyd at the intersection of 38th St. and Chicago Ave. in Minneapolis, the site where George Floyd was murdered. The intersection has been blocked off to traffic since people started to gather, bring offerings, and create art. Today George Floyd Square is a site of memorialization, community gathering, social justice and mutual aid work, artistic expression, and ongoing protest. Volunteers tend to the site daily, led by Jeanelle Austin, a native of Minneapolis who returned to her neighborhood to care for the site. For more, see Carlson, “Improbable Joy,” https://nationsmedia.org/improbable-joy-jeanelle-austin-speaks-out-about-george-floyd and Ajasa, “‘It’s for the People’: How George Floyd Square Became a Symbol of Resistance–And Healing,” https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/mar/27/its-for-the-people-how-george-floyd-square-became-a-symbol-of-resistance-and-healing.

4 Kenda Zellner-Smith and Leesa Kelly started the organizations Save the Boards and Memorialize the Movement separately to collect and preserve plywood boards following the George Floyd Uprising. They eventually joined together to form Save the Boards to Memorialize the Movement and collected over 900 boards. Recently they have decided to pursue their work as separate organizations.

Works Cited

Ajasa, Amudalat. 2021 “It’s For the People”: How George Floyd Square Became a Symbol of Resistance—and Healing.” The Guardian, March 28, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/mar/27/its-for-the-people-how-george-floyd-square-became-a-symbol-of-resistance-and-healing. Accessed May 17, 2021.

Carlson, Joseph. Improbable Joy: Jeanelle Austin Speaks about George Floyd, Racial Justice, and the Discipline of Hope. Nations, June 28, https://nationsmedia.org/improbable-joy-jeanelle-austin-speaks-out-about-george-floyd. Accessed May 17, 2021.

Hall, Stuart. Constituting an Archive. 2001. Third Text. 54.15:89-92.

Jones, Seitu. Personal Interview. August 11, 2020.

Tran, Ngoc Loan. 2016. Calling IN: A Less Disposable Way of Holding Each Other Accountable. In The Solidarity Struggle: How People of Color Succeed and Fail At Showing Up For Each Other In the Fight For Freedom, ed. Mia Mckenzie. BGD Press, 59-63.

What to Know About the Death of Daunte Wright. 2021 New York Times, April 23, https://www.nytimes.com/article/daunte-wright-death-minnesota.html. Accessed May, 17, 2021.

Yuen, Laura, Nina Moini, and Riham Feshir. 2021. Here’s What We Know about the Fatal Police Shooting Outside a Minneapolis Gas Station. MPR News, January 1, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2021/01/01/heres-what-we-know-about-the-fatal-police-shooting-outside-a-minneapolis-gas-station. Accessed May 17, 2021.