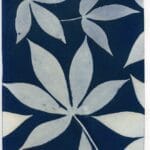

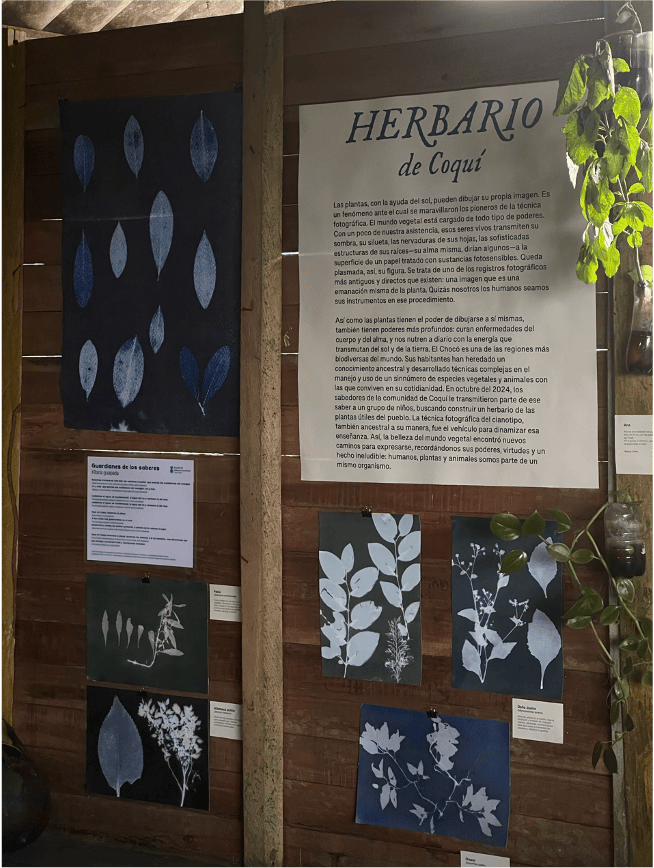

Cyantotypes of Matarratón Gliricidia sepium, Coca Erythroxylum coca, Papa Achín Colocasia Esculenta.

Chaparro Curatella americana, Papo Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, Escobilla Sida rhombifolia.

The nonprofit organization Casa Múcura has been working with the community of the village of Coquí, Chocó, in Colombia’s Pacific coast, for seven years in multiple participatory projects aimed at valorizing, promoting, and preserving traditional knowledge and ancestral ways of living in one of the world’s most biodiverse regions. In 2024, funded by the Seeds of Innovation grant awarded by Fondo Acción, Casa Múcura’s team implemented the Listening to the Earth project, which set out to organize creative workshops for Coquí’s elders to share their knowledge of medicinal plants with the village’s children and teenagers.

In Casa Múcura’s School of Ancestral Knowledge, 35 elders (sabedores) and 15 children from Afro-Colombian and Indigenous Emberá backgrounds worked together with a team of four Casa Múcura members using Participatory Action Research methodology (PAR) to create what the community called the Herbarium of Coquí. The participatory project lasted one and a half years, during which organizers and community members used different tools to document their traditional plant knowledge as part of the educational program of the School: storytelling, focus groups, community dialogues, and intergenerational workshops for the creation of a cyanotype herbarium.

Context: The Community of Coquí and the School of Ancestral Knowledge

Coquí is a territory named by the Indigenous Emberá to bind the connection between the land and the ocean. For the locals, the rhythm of the name signifies the moment when the waves hit the land. This village, on the Pacific Coast of Colombia, is part of the municipality of Nuquí, in the Chocó department—one of the world’s rainiest and most biodiverse regions. With a population of 120 people, Coquí is inhabited by an Afro-Colombian community, locally identified as a Black community, and three families of Indigenous Emberá who spend occasional seasons in the town and other seasons in the forest.

The landscape of Coquí is complex, mutable, and fertile. Everything in this territory is in constant movement. The river, the mangrove, the ocean, and the rainforest develop their cycles of regeneration; they are mediated by the highest pluviometry in the world, and the biodiversity of the Biogeographic Chocó (Suman 2007). This deep Western side of the Pacific Ocean is part of the Tribugá Gulf, a natural hotspot for the protection of marine and land species (MissionBlue 2019).

The tropical weather is marked by a constantly cloudy sky that comes with fog, a harbinger of rain, which is accompanied by thunder—shock waves that, with a great amount of heat, arrive to mix with the cold air.

The community of Coquí has organized itself over time through various collective projects centered around eco-tourism and food production. Coquí has a public school from 1st to 5th grade, forcing children and parents to leave the territory to complete high school or access better education. The departure of entire families and generations has led to the loss of opportunities for intergenerational involvement and the development of community projects.

In response to these needs, the local School of Ancestral Knowledge emerged as a space that allows the children who still live in Coquí to engage not only in traditional trades but also in the community projects of their territory, promoting organic learning of traditional crafts through practice. The School of Ancestral Knowledge fosters a space for the community elders to teach local trades through an environmentally centered and holistic education; it is a platform to provide pedagogical content designed by and for the territory. This process has resulted in academic outings to fish and explore the jungle, documenting plants through art, creating original dances and songs, building the community garden of the Coquí School, and training children to be tour guides for the Museum of Coquí, a platform to show and reflect on the natural and cultural heritage of the Pacific Region of Colombia.

The Documenting Process

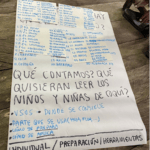

For the creation of the Coquí Herbarium, we conducted more than seven focus group sessions with local and traditional plant knowledge holders, children, and youth. In these sessions, each lasting over three hours, we compiled a list of the 100 most important plants for the community. The community identified the medicinal, nutritional, and esoteric properties of the plants used by both the Emberá Indigenous communities and the Afro-Colombian community of Coquí. We also created detailed information sheets that included the plants’ uses, preparation methods, contraindications, and the specific part of the town where each plant can be found.

To encourage knowledge of local plants, we held a weekly workshop for a year with traditional plant knowledge holders and children at the School of Ancestral Knowledge. Those sessions were intended to strengthen their understanding of plants through practices such as medicinal baths, poultices, aromatic herbs, and sensory foraging walks through the jungle, river, and village. These activities helped identify the most important plants for the community and prompted reflection on the relationship between bodily health and the care of the land.

To encourage knowledge of local plants, we held a weekly workshop for a year with traditional plant knowledge holders and children at the School of Ancestral Knowledge. Those sessions were intended to strengthen their understanding of plants through practices such as medicinal baths, poultices, aromatic herbs, and sensory foraging walks through the jungle, river, and village. These activities helped identify the most important plants for the community and prompted reflection on the relationship between bodily health and the care of the land.

The practical training sessions on medicinal plants for the village children were also integrated with the creation of situated narratives—creative writing sessions in which the students reflected on their favorite plants and the powers they would like to gain from each one. In these sessions, they wrote about the healing powers of aloe vera, the sweetness and fragrance of basil, the flavor and protective qualities of chili pepper, and the softness and shielding nature of cotton.

After more than 20 sessions with the community’s traditional knowledge holders and the schoolchildren on medicinal plants and their properties, the community discovered a new way to connect with plants through cyanotype workshops with the artist Miguel Winograd. In the final publication of the Herbarium of Coquí, cyanotypes of each selected plant were used, and the information shared by the community during the collective work sessions was documented. This included details on more than 90 locally used plants for bodily care.

Cyanotype Photograms Workshops

The Herbarium of Coquí is a platform to reflect on the local use of plants, the daily connection with the territory, and the local knowledge and the community identity around the meanings of place, health, and traditions. By bridging intergenerational gaps and honoring both Afro-Colombian and Emberá wisdom, the initiative fostered a deeper understanding of biodiversity and ecological stewardship among the younger generations. The platform now serves as a document and exhibition in the local Museum of Knowledge for ongoing community education, cultural revitalization, and environmental advocacy, rooted in the voices and visions of Coquí’s people.

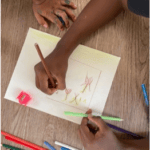

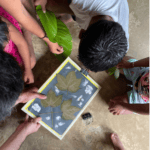

In October 2024, the project’s workshops culminated in a weeklong exercise in which elders, children, and mediators made cyanotype photograms of more than 50 different plants, reinforcing among the children the ability to identify myriad botanical species and effectively creating a visual catalog of the Herbarium for future practical and pedagogical uses.

Cyanotype is one of the earliest photographic techniques made by mixing iron-based solutions that form a light-sensitive substance when brushed onto paper or fabric. The technique was developed by the great 19th-century British naturalist, Sir John Herschel, and used to print history’s first photographic herbarium, Anna Atkins’s 1843 British Algae. Rather than photographing botanical specimens, Atkins placed them directly in contact with the sensitized paper and exposed them to sunlight. The treated paper thus registered a direct and minutely detailed imprint of the plant’s silhouette and the nervation of its leaves, a blue trace of the specimen’s variable opacity, or a straight “emanation of the referent,” as Barthes would have it. (2010) The iron’s reaction to light resulted in an image formed by a range of shades of Prussian blue, thus its name: cyantype from kyanos, the Ancient Greek term for dark blue. Recent research has highlighted the entanglement of plants and humans in the development of early photographic techniques in the 19th century. The photogram—a cameraless “proto-photographic” procedure whereby leaves or other objects are placed in contact with light-sensitive paper and exposed to light—is the paradigmatic example (Hoffman 2024).

Relatively simple to learn, cheap, and non-toxic (as opposed to silver-based processes), cyanotype is usually taught as an introduction to the rudimentary bases of photographic technique (James 2016). Without delving into the chemical details, children of all ages can experiment with making prints of leaves, roots, branches, etc. and see concrete, palpable results in only minutes. Despite the difficulty of an environment with 100 percent humidity (and thanks to the intensity of the intermittent tropical sun) the participants in the workshop—children ages 2-12 and elders 40 and older—intuitively grasped the essence of cyanotype technique. It also proved to be a stimulating means to strengthen the elders’ lessons on the exuberant diversity of local medicinal and edible plants that they had been teaching the children in the School of Ancestral Knowledge. Children, elders, and the members of Casa Múcura’s team, in effect, collectively created a beautiful visual catalog—an Herbarium—of more than 50 medicinal plants. The images were then collated with the year-long participatory research surveying common and scientific names of species and detailing their medicinal uses and the methods to prepare and apply them. This comprehensive research was published online as part of the results of Fondo Acción’s grant.

This creative and collective documentation (artistic botanical photograms, situated narration, and vernacular medicinal pharma-copeia), has also circulated through diverse outlets: interactive museum exhibits, academic publications, art objects, clothing, card games, etc. The participants in Coquí’s workshops made cyanotypes of their favorite plants directly on t-shirts which proved wildly popular. The Herbarium’s images reproduced in different materials and scales were installed as an exhibition in Coqui’s Museum of Knowledge. Different versions of the exhibit were also later installed in the Explorer’s Club and Colombian Consulate in New York City. The School is additionally planning to publish the Herbarium as an interactive card-game/photobook. The diverse means to share this multidisciplinary research project with audiences are all aids to promote, preserve, and protect the profound and intimate knowledge that local Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities have of their territories.

- Potra

- Achin o Papa China | Malanga

- Yuca | Cassava

Conclusion

At the beginning of the project, the children and youth began to recognize that plants play a role in healing the body. They identified that caring for the territory was related to garbage collection and reducing tree logging. By the end, the group from the School of Ancestral Knowledge had learned to recognize, gather, and identify by name more than 30 medicinal plants, which they can use to make drinks, baths, and poultices. On the other hand, they associated caring for the territory with protecting the mangroves, collecting and safeguarding local seeds for planting, and the care and use of plants as a fundamental part of their culture and food sovereignty. (This information comes from a quantitative analysis carried out at the beginning and end of the project.)

This region of the Colombian Pacific is environmentally unique as much as it is threatened by myriad destructive forces. Several armed groups involved in the protracted Colombian internal armed conflict exert different degrees of control over the territory, which is a strategic launching point for cocaine exports. The majority of local communities live below the poverty line. Despite its mega-biodiversity, currents bring waves of micro-plastics to local beaches, some coming from as far as the Asian shores of the Pacific Ocean. The lack of economic opportunities, among other factors, pulls younger generations away from the ways of living in and knowing their natural habitat inherited from their elders. Projects such as Listening to the Earth highlight the importance of promoting and protecting the transmission of this knowledge. This project could work as an example for communities to create participatory methodologies that allow children and elders to share their interests, communicate and experiment with different tools to co-create new ways of learning.

Alejandra Salamanca is an anthropologist with an MA in Anthropology of Food from SOAS University of London. She has worked for more than nine years in the creation of participatory methodologies, community projects, and associative strategies, focused on food heritage, gender, and biodiversity. She is currently professor at the Universidad del Rosario. She has been involved in the creation of participatory research initiatives in New York and London with organizations such as Migrateful UK and Los Herederos NYC. She facilitates food sovereignty and agroecology processes with migrant populations, Indigenous peoples, and Black communities in Colombia and the United Kingdom. Alejandra is co-founder of Casa Múcura and the current project director. She is a columnist for several alternative media and author of the books Abrazar la tierra: Memorias colectivas de la Cocina Ancestral de Coquí, Chocó, 2022 winner of the Best African American Cookbook award at the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards 2023, and Sucre Sabe Diferente, 2023. Both book projects explore the intersections between identity, heritage, food, and ecology.

Miguel Winograd is a Colombian photographer and historian. He is interested in the complex interconnections in the landscapes of the tropical Andes, histories of environmental resistance and regeneration, and narratives of social conflict. His work has been exhibited internationally and published in different media, including The New York Times, The New Republic and El País. He teaches courses on photographic technique and the history of photography.

Find more at Miguel Winograd https://www.miguelwinograd.com.

Casa Múcura is a nonprofit organization dedicated to fostering peace, cultural education, and sustainable development in the Gulf of Tribugá, promoting community-led initiatives that honor the land, support collective economies, and strengthen the social fabric, with a special focus on creating spaces for dialogue, cultural exchange, and holistic development. The mission is to co-create spaces where creativity, reflection, and dialogue intertwine with ancestral knowledge, fostering generational renewal and the self-management of community projects.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. 2010 [1980]. Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang.

Hoffman, Felix. 2024. The World on the Wayside and the World on the Brink: Images of Plants from Anna Atkins to BASF. In Science/Fiction: A Non-History of Plants., eds.Victoria Aresheva and Clothilde Morette. Leipzig: Spector Books.

James, Christopher. 2016.The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes, 3rd ed. Boston: Cengage Learning.

MissionBlue. 2019, https://mission-blue.org/2019/08/stop-the-tribuga-gulf-sea-port-latest-hope-spot-in-colombia-celebrates-wondrous-biodiversity-and-need-for-official-protection, August 28..

Suman,Daniel. 2007. Globalization and the Pan-American Highway: Converns for the Panama-Columbia Border Region of Darién-Chocó and its Peoples. 38 U. MIA Inter-Am. L. Rev. 549, https://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol38/iss3/3.

URLs

Fondo Accion https://fondoaccion.org

Casa Murica https://www.casamucura.com