The Stars Program at Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School

by Lucinda Megill Legendre

For a middle-school student who is just starting to learn English in the United States, myriad factors can contribute to a sense that one is beginning an insurmountable task. Not only is the English language unwieldy, wild, and unknown, but many students in the Stars Program at the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) in Philadelphia also come with limited schooling, traumatic experiences—or both—in their past or their present. They are not just learning grade-level reading, writing, math, science, and social studies in a brand-new language, they are also learning to navigate and interact with an educational system and peers in a new culture. The prevailing atmosphere of xenophobia, racism, and white supremacy demand a particularly meaningful education for these marginalized students, one that will strengthen and empower them. In the Stars Program, students are not only learning the use of ethnographic tools and habits of mind to build their efficacy and sense of empowerment, they are also effectively gaining English proficiency in a short amount of time.

Serving immigrant students and English learners is at the core of the mission of the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School. FACTS was born from a long history of advocacy and service to immigrant communities in Philadelphia. Local nonprofit organizations Asian Americans United and the Philadelphia Folklore Project worked together to design a school that would be a safe and joyful place for immigrant students, and all students. After years of work and planning FACTS’ charter was approved in 2005. FACTS worked to build a school that would integrate the community knowledge and folk arts of the surrounding Chinatown neighborhood and those of other groups in the city as well. The founders created daily and yearly rituals that allow for reflection and celebration of our shared values. Many of the shared values are summarized in the school pledge. “We care for one another and learn together. … Our elders know important things and we take time to learn from them… All people have a right to use their own language and honor their own culture,” are just a few of the lines that students and teachers recite and refer to regularly. Through the hard work of founders, teachers and students FACTS has received many awards and recognitions not only for the academic success of our students, but also for our caring and safe community. We know that folk arts education and the practices that value community knowledge are keys to our students’ academic success. Seeking to serve a diverse immigrant community, the founders of Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School had long envisioned a special program to support students who were new to English in middle school. Finally, in early 2017, we received permission for an expansion that included a special class for beginning English learners (ELs). In September 2017, the Stars Program welcomed its first class. Fourteen students from ages 11 to 15 completed the first year. These students came from many different countries and backgrounds, including refugees from Syria and Central Africa and immigrants from Asia. Some have had six or seven years of schooling, some fewer than three. Some students are confident with academic tasks, others long to develop skills that will allow them to accomplish their goals in education. This June, the second year of the Stars Program finished with 20 students.

Stars students are in our main self-contained classroom for our morning community-building time, followed by English, math, science, and social studies. They travel from our classroom to study art, music, Chinese, and PE with our specialist teachers. In addition, a special folk arts class has been designed for them to experience different folk arts from our community. Stars students join other middle schoolers for lunch, recess, and extracurricular folk arts ensembles. The program design is that by being mostly self-contained and sheltering grade-level content within the larger task of English learning, students may increase the speed and depth of their language learning, more so than if they were simply supported in the general education classroom.

As our school’s name suggests, folk arts education and ethnographic research are core to how we provide all our students with a high-quality, 21st-century education. As we designed Stars, it was particularly important to us to use this same educational approach with all its tools and practices to provide newcomer students with a high-quality educational experience too. We are guided by our intent to design effective education that also serves to break the paradigm that students who are learning English are limited or lacking because, in fact, we know that immigrant students bring many gifts and experiences that enrich their education and those of their classmates.

Why Ethnography?

In many newcomer classrooms students receive workbooks and textbooks to introduce and allow students to practice basic vocabulary and language structures most used and needed in English. Good programs blend academic English and beginning social and instructional language. In many programs for middle-school newcomers, teachers’ guides recommend that students conduct dialogues or interviews, often pre-scripted or using circumscribed vocabulary or structures. One may gather from the structure and sequence of these curricula that students new to English need specialized, limited practice with English until they may be ready for harder, more challenging or real-world tasks. Practitioners and researchers have, however, found that the opposite is true. As Celia Roberts found in her book Language Learners as Ethnographers, students learning another language were able to complete meaningful ethnography research (2001). Roberts states, “Our experience and those of others (Jurasek 1996) is that those students with the most advanced language skills do not necessarily undertake the most interesting ethnographic projects or produce the best ethnographic assignments” (2001, 5). With her case study of undergraduate language learners in Europe she found that, “introducing an ethnographic approach can contribute to enhanced language learning” (Roberts 2015).

Others who work in the field of second language acquisition have argued that meaningful context is powerful to successful language learning, as opposed to learning isolated lists of words separated from their use or meaning. This research-based theory shows that students will learn and remember more vocabulary if words are embedded in meaningful context (Brown 2012). The Stars Program uses the cultural contexts that students find themselves in. Our classroom, school, neighborhoods, and families become the contexts for learning and using new and vital language. As Roberts succinctly asserts, “cultural learning is language learning” (2001, 5). Scholarship about ethnography and language learning have been foundational as we have developed a curriculum that goes beyond the workbook-based curriculum typical for newcomer programs.

In developing Stars, we have also been informed by the research and practice centered around trauma-sensitive schools. In a particularly practical book Susan E. Craig and Jim Sporleder lay out numerous recommendations for supporting students who have or have had trauma experiences (2017). Based on new understandings of not only trauma’s impacts but also adolescent brain development, they recommend practices that demand a curriculum that goes beyond the workbook. A few highlights include: “Get to know your students. Find out what matters to them and integrate topics of interest into content instruction… Design instruction that works with the brain’s plasticity to strengthen neural pathways associated with higher-order thinking” (30); and, “Use flexible groups for activities that involve student collaboration to help teens gain insight into the complexity of their behavior and that of their peers” (Craig and Sporleder 2017, 86). Based on this and other research, Stars middle-school students are not only developing English proficiency but also engaging in fostering higher-order thinking through ethnography that investigates culture and its complexity. Our meaningful ethnographic inquiry and research are supported by specific techniques to scaffold language learning. Students are able to conduct scaffolded ethnographic research that allows for authentic use and practice with social and academic language.

Curricular Design that Centers Ethnography

The curriculum we designed and have begun to implement for the Stars program is rooted and centered in building the capabilities and capacities of ethnographic inquiry and folk arts education. Centering ethnography allows the program to meet its objectives of accelerated language learning and also provides a supportive environment for students with past or current trauma. Centering ethnography includes beginning the year with investigations of people and places in and around our classroom and school community. These investigations replace the workbook-style memorization and limited application of classroom and school vocabulary (although workbooks and other printed materials are used for introduction or supplemental practice). More typical curriculum for middle-school newcomers would consist of a textbook page with large, labeled images focused on grammar teaching points or new vocabulary to be developed. There may be charts and examples with explanations. Then there is a series of questions for the students to answer. Good textbooks provide ideas for other extensions and interactions that teachers can lead to deepen learning, and they try to reflect the ethnic and racial make-up of modern English learners. However, no textbook can provide the interactive, higher-order thinking and collaborative work that teachers who know the students can. Centering ethnographic inquiry and folk arts education happens in our social studies and English language arts curriculum. Throughout the two-year curriculum cycle, students research components of neighborhoods, foodways, and public transportation. In the unit about Philadelphia neighborhoods students develop inquiry and research skills and also engage in meaningful use in context of both everyday social and academic vocabulary to describe people and places in neighborhoods. Again, this hands-on research replaces the very limited exposure and practice found in many curricula for newcomer English language learners while providing the collaborative and higher-order thinking recommended for trauma-sensitive schools.

The Stars curriculum has been designed to teach to the tangible skills and intangible habits of mind as Linda Deafenbaugh lays out in her chart on Teaching Ethnographic Inquiry in Folklife Education (forthcoming). The process of ethnographic research provides meaningful opportunities to develop necessary English language skills and vocabulary and allows for supportive practices for students with trauma, such as collaborative learning, investigation of interests, and research into complex behavior. For example, the first step of ethnographic inquiry, data collection, is very important and relevant for middle-school language learners. By building the tangible skill of observation, students are purposefully acquiring the language to label and describe their new environment and expanding the cognitive groundwork for deeper exploration and investigation of norms and culture. A community of respect and support is built by making time for and teaching to the skill of observing the objects and people in the classroom, the school, and the neighborhood: skills that the students must have to survive. The recognition of the work they are already doing to interact in a new cultural context helps students gain confidence without feeling bored and belittled by simple memorization and book work. It also puts them into a position of decision making and control. Instead of filling in the blank within a sentence on a page, students are asked, “What do you notice?” This kind of open-ended inquiry allows for student creativity, voice, and autonomy to be centered in instruction.

Middle-school language learners are involved in a constant task of data collection by monitoring their environment trying to understand the names of people, places, and things, as well as learning and adjusting language and behaviors to fit (or defy) perceived cultural norms. Making this culture and language learning part of the curriculum and giving it an academic frame recognizes their daily work and provides the classroom community as support in this shared task. Ethnography centered in the curriculum also conveys a message greatly valued in folk arts education, the everyday is precious and worthy of study in school. Other examples of data collection centered in English learning are interviewing classmates and teachers in the building. At the beginning of the year, asking classmates about their background and interests is beautiful territory for authentic language learning and meets developmental social needs to build a caring community. Here again, the recognition of the work they are already doing teaches that our classroom is a place where your needs are seen, respected, and valued. The practices of folk arts education and ethnography are centered in the Stars classroom because they are effective for language learning and essential for building a supportive community to allow students with trauma feel safe in the classroom environment (Craig and Sporleder 2017).

Working through the next steps of ethnography—data analysis and re-presentation—also provides benefits. In the first few weeks of school, students interview a partner from a country different from their own and then report to the class their analysis of ways they are similar and different. This activity is powerful and sends a message that builds community while supplying meaningful language practice. Building community by getting to know each other allows students with trauma to feel more comfortable.

Conducting Ethnography Using Language Supports from the WIDA Framework

Vital to the successful teaching of English learners is an understanding of the progression of acquiring a new language. Most states and districts across the country use the research-based standards and assessments developed by the World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) consortium. WIDA research and frameworks are anchored in the philosophy that “Children and youth who are linguistically and culturally diverse, in particular, bring a unique set of assets that have the potential to enrich the experiences of all learners and educators. Educators can draw on these assets for the benefit of both the learners themselves and for everyone in the community. By focusing on what language learners can do, we send a powerful message that children and youth from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds contribute to the vibrancy of our early childhood programs and K–12 schools” (Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System 2018). This philosophy has guided the research and creation of tools for teachers and families that describe what students can do at the various levels of English language proficiency. By learning the characteristics and possibilities for language understanding and use, teachers can design meaningful and engaging activities for students at any level of English language proficiency. This is also true when it comes to designing and guiding students in folk arts education and ethnographic inquiry. The WIDA Performance Definitions for the Levels of English Proficiency in Grades K–12 guides teachers to understand what types and forms of language can be expected in levels of English language proficiency (Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System 2018).

The first two levels are where most Stars students are along the continuum of language learning. Consequently, when designing activities I know I can expect students to be able to use “words, phrases and chunks of language” independently to talk about and write about what they are seeing and understanding. Students in the first level need and can use “pictorial or graphic representation of the language in the content areas.” It also means that if students need to do more than these types of responses they will need support and scaffolding, such as providing sentence frames to allow students to begin to form more complex ideas, or encouraging students to use translation to their first language to access more sophisticated language for complex concepts or ideas.

Another helpful tool for thinking about the language abilities of English learners are the Can Do Descriptors also published by WIDA (2014). These are more specific to the various language domains and key uses of language and provide helpful information to guide teachers in supporting student learning. The descriptors detail supports for language learners in the beginning levels and a vital support is found repeated throughout the descriptors and visuals. For example, students at Level 1 can “Indicat[e] relationships by drawing and labeling content-related pictures on familiar topics” (WIDA 2014, 7). Or at Level 2 students can “Sequenc[e] illustrated text of narrative or informational events” (WIDA 2014, 5). In the two years leading the Stars through these units, I have found that when students have access to and use visuals as part of their data collection, data analysis, and re-presentation, they are able to engage more deeply in conducting rich ethnographic inquiry.

Applying Linguistic Supports and Frames When Conducting Ethnographic Inquiry

Within days of arriving at FACTS in September 2017, Stars students embarked on their first journey into ethnographic inquiry. We began by studying the people and roles in the classroom. After practicing and generating some shared vocabulary for actions and behaviors, students were given vocabulary cards of the keywords with visuals. They were encouraged to translate the words into the language of their primary literacy. We practiced using and acting out these words. We read and wrote about these words. Then I asked students to conduct observations and record their analysis of the different roles in the classroom (students and teachers, in this case). Students used a Venn diagram to show their findings. They then went to re-presentation and created classroom movies with narrations and visuals to show the actions of different people. Each student wrote their own script, but the project required them to work together to create photographs of the behaviors they observed in the classroom. Using Windows MovieMaker, students imported and labeled their visuals. Using a voice recorder on our tablets they recorded the narration, then they added the audio track to their movies. After the movies were finished, we watched them all. While watching, students took notes about the similarities and differences in what data various students decided to include.

Instead of completing workbook pages with cartoon images of different actions and people in the classroom, the students had just conducted their first, scaffolded ethnographic inquiry. They were able to proceed through the steps from data collection, analysis, and re-presentation (and some additional reflection and analysis at the end). They were supported to use and understand general classroom words, phrases, and simple sentences as outlined in the WIDA Performance Definitions. We used translation to students’ primary language, visuals, and multimodal practice to develop understanding in the ever-present context of our classroom to support effective language learning. And potentially most importantly, we built our classroom community through a collaborative project of posing for and directing classroom action photos. I think back fondly at the teamwork and determination of the students to show the verbs we had been learning, helping classmates hold their arms just so or stand in the best place in the room to show the meaning. I still hear the laughter and nervous giggles of middle schoolers getting their pictures taken. These experiences, along with supporting each other to record and edit their narrations, help to build our community and make a safer space for students with trauma.

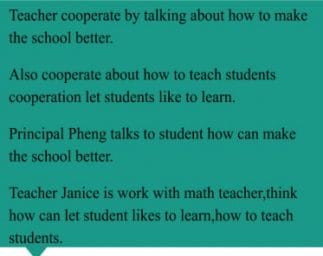

After exploring the classroom, we moved on to the school community interviewing and analyzing data about who is in our school, their roles, and what we have learned about our school. The Stars students’ re-presentations for this inquiry were books that they shared with first graders. In one student’s book she wrote, “Everyone at FACTS cooperates,” and then explained by using evidence from our research, as seen here in the page from her book (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stars student interview project book page example.

For this project the students went out in teams and took turns interviewing teachers in the school. They recorded the interviews using our tablet voice recorders so that they could be transcribed into a chart in a shared Google doc. Once all the data had been entered, students set out to analyze the data and come up with a thesis to support with evidence from the research. Some students, depending on language proficiency, were given sentence starters to help guide their thesis writing. Once they had a plan, they created books using Google slides into which they inserted Google images or photographs they had taken. Finally, they read their books aloud to small groups of first graders who were also engaged in a social studies unit of study of the school community and roles of different people in the building.

In this project you can find similar centering of ethnographic inquiry to propel language learning and create a trauma-sensitive learning environment. Students worked with an additional tool of ethnography: interviewing. We developed questions together as a class and the students took turns conducting interviews after they had practiced with each other in the classroom. In a typical curriculum for newcomers there may be an activity to “Interview a classmate using the question words.” This is lovely practice, but it is not as meaningful as asking real questions to get real answers from the principal, the social worker, and the custodian. Practicing wh- questions ahead of time with a classmate does help students who are ambivalent, even terrified, about approaching and interviewing an adult they may have seen but do not know. Luckily FACTS staff are very patient and supportive, which helps the students doing this task. Thus, not only do students learn new skills and vocabulary, they discover what a resource our caring staff is. Taking the safe but scary risk of conducting an interview is far more powerful than just being told “all the adults in the building are here to help you.” I could have also told the students that many of the staff in our school come from countries other than the U.S. or that people in our school also speak more than one language, but these important facts were more meaningfully learned by students analyzing their own data and coming to those conclusions themselves.

In this school interview example, you can see how the three elements of our curricular design are intersecting and overlapping in important ways. Dividing the work of transcribing interviews was done as necessary and meaningful collaboration—we got much more done together than we could have by ourselves. Analyzing data required some real higher-order thinking in pattern finding and meaning making. Higher-order thinking has been identified as important for helping students with trauma backgrounds, but it is also important for using academic language. Finally, the re-presentation of reading our books to first graders enforced a guiding principle of our school’s design, multi-age community building. And, of course, conducting interviews chockfull of vital school vocabulary, listening to them, and then transcribing them is a natural way to expose students to new vocabulary many times over. Students then analyze these ideas, write them, type them, and provide images to illustrate them. And, finally, they rehearse and then read those words to an authentic audience! The amount of meaningful practice with real-life vocabulary that is both useful and valuable in their daily context is far more valuable than filling out 25 workbook pages.

Expanding Inquiry into the Larger Community

Our use of ethnographic inquiry in the Stars classroom has not been limited to the basic social and instructional language of school. In the 2018-19 school year, after conducting interviews of classmates and then teachers in the building, students produced a directory for parents. Next we ventured out into our city to explore the neighborhoods. A guiding principle that I have employed in designing inquiry for my newcomer students is to set up a framework that centers around a core group of vocabulary words. In the classroom project, it was a list of classroom verbs. For our neighborhoods inquiry, it was the key ideas from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1958). These ideas helped us understand and explore the idea that neighborhoods help people take care of their wants and needs. The keywords of shelter, safety, community, belonging, medical care, and others helped guide our inquiry. We set out first on foot into our school’s Chinatown neighborhood and then via public transit to other neighborhoods to explore how different neighborhoods help people get their wants and needs. We also explored how different aspects of neighborhoods make us feel. Embarking on this exploration can sound complex and unwieldy, but we took the ethnographic inquiry step by step and used the tools and techniques outlined in the WIDA framework to support language learning. During the whole process we were engaging the strategies and understandings of trauma-sensitive schools to support students’ needs.

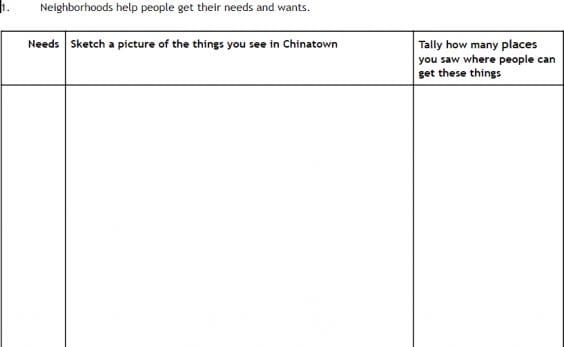

There were many steps and aspects of the inquiry, but I outline a few here and explain how they were used to support language learning and learners. Our first task was developing and teaching to this core list of vocabulary and ideas. We spent days exploring, showing, acting out, and translating the keywords like community, safety, and shelter. We then practiced our observation and note-taking skills by visiting the cafeteria to see how the cafeteria was providing for students’ needs. I can’t tell you the joy that leapt from my heart when a student sketched and labeled a teacher supervising a group of tables in the “Safety” section of the chart (Figure 2). It was proof to me that with the right supports (language practice, time, and a clear task) students, even those with minimal English, could really make use of ethnographic tools and make meaning about their daily lives. And then like popcorn, the brilliant ideas and insights just kept coming: Another student sketched the circle tables and identified that they provide community, and on and on. Now that we’d had our practice in the confines of the school cafeteria it was time to take the show on the road.

Figure 2. Data collection tool.

Students selected different aspects of the hierarchy of needs to investigate the streets in Chinatown. Their task was the same as in the cafeteria: Observe the neighborhood to find examples of how it might be helping people meet needs. Their tool was the same, a chart with their need and a large box to sketch or describe the things they were seeing. Students could sketch or take notes in English or the language of their primary literacy (Chinese, Arabic, Spanish, etc.). For some students this tool worked well, for a few it was too much to keep track of. Those students were equipped with a tablet and tasked with taking pictures of the things they saw for their needs group so that we could sort the photos later, back at school. We went out in small cooperative groups in which the students were working together to assess the diverse needs people have.

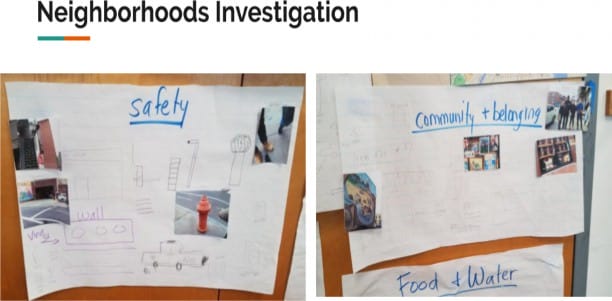

The next day we needed to compile and sort our data. We used the very sophisticated technology of large pieces of chart paper. The students sorted and labeled their findings onto the chart paper (Figure 3). They noticed the things that many people noticed and explained to their peers and to me why the fire hydrant, for example, was added to the safety group. This was in a way re-presentation and in a way a tool that allowed for analyzing. We were able to see which needs Chinatown was very obviously able to meet (food!) and which needs you could also see if you looked closely (community and belonging).

Figure 3. Data analysis.

We repeated these steps in other neighborhoods, adding additional research techniques and interviewing. Always speaking, listening, reading, and writing the same centering keywords (obviously adding more vocabulary for students who could), always making and collecting visuals, and always working in supportive, collaborative groups.

When students were finished, they turned their inquiry to their own neighborhoods to observe and analyze the ways they do or do not meet their needs and what can be done about that, either to celebrate or make change. The student work, posters or letters, showed they had an understanding of the core vocabulary by providing examples and explanations from their observations and analysis. It was exciting for the class to compare their neighborhoods with those we explored together and discuss their opinions about what they and their neighbors need. I was surprised by how many students decided to choose something to praise about their neighborhoods—celebrating the ways where they lived provided for their wants and needs.

This was a complex unit. But it further proved to me that ethnographic inquiry could be used to meet the core goals of our Stars Program: providing meaningful and effective language learning while building the community and academic skills. Ethnographic inquiry also allows us to meet so many of the goals of our school using folk arts education to provide students the space to explore and analyze, critique, or celebrate their community and their cultures.

Goals for Future Study

Now that we have completed the two-year cycle of our curriculum, it’s time to do more research and analysis. With the data we receive from this year’s WIDA ACCESS for ELs 2.0, we will be able to assess the ways in which our curriculum is meeting our language proficiency goals and the areas that we need to strengthen.

Qualitative data collection about how the students feel and understand the purposes and methods is also very much needed. I have many theories about how students are experiencing different aspects of our practices and our curriculum based on observations, but more systematic data is needed to get a more complete picture of what the student experience is with this curriculum. Is it as empowering as we intend? Are students able to see how they are building their skills and their community? Do students feel successful and engaged in asking questions about their cultural contexts?

And, finally, long-term, what are the effects of this curriculum? Are students building skills that will guide them in high school and college with cooperative and project-based learning? Are students able to use observation, analysis, and meaning making as they move through different cultures and contexts? Will they use their voices and their data to share their important perspectives?

Lucinda Megill Legendre has been teaching at the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School in Philadelphia for ten years, as English Language Development teacher and now as the teacher for the Stars Program. She also serves as the Social Studies Coordinator.

Works Cited

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. 2018. Mission and History. WIDA, 2019, https://wida.wisc.edu/about/mission-history.

Brown, H. H. Douglas. 2012. The Key to Learning a Language Is Context. Language Seed, February 24, https://languageseed.com/2012/02/24/the-key-to-learning-a-language-is-context.

Craig, Susan E. and Jim Sporleder. 2017. Trauma-sensitive Schools for the Adolescent Years: Promoting Resiliency and Healing, Grades 6-12. New York: Teachers College Press.

Roberts, Celia. 2001. Language Learners as Ethnographers. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Maslow, A. H. 1958. A Dynamic Theory of Human Motivation. In Understanding Human Motivation, eds. C. L. Stacey and M. DeMartino. Cleveland, OH: Howard Allen Publishers, 26-47. doi:10.1037/11305-004.

WIDA. 2014. WIDA Starter Pack. Madison: Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System, on Behalf of the WIDA Consortium.

URL

WIDA Can-Do Descriptors: https://wida.wisc.edu/teach/can-do/descriptors