We are sitting in the back of the Community Bookstore in Park Slope, Brooklyn, with Ezra Goldstein, the store’s co-owner, as he participates in a model oral history interview. Alongside owning this community anchor, Ezra has lived in the Park Slope neighborhood for over 30 years and has a thoughtful approach to discussing changes he has witnessed. His small, independent bookstore is a community touchstone and staple for area residents, but for many students visiting from a neighboring high school, Park Slope Collegiate (PSC), it is often an unrecognized storefront passed by to or from school.

This interview is part of a process for teaching students to conduct their own oral histories, one piece of a curriculum implemented by the Urban Memory Project (UMP). UMP has been working with these students and their social studies teacher for the past month studying the history and current issues that shape their Brooklyn neighborhoods. Students have built background knowledge through field documentation and text-based research and are now preparing to enrich their understanding of their communities through talking with the people who live in them.

One of our favorite examples of the interview modeling method is the conducting of an oral history with Ezra. To interview him, students walk from school to his bookstore, one class at a time, and arrange themselves in seats in the cozy children’s book section. Ezra and the UMP educator sit on stools facing the students and are sometimes joined by the bookstore’s notorious and grumpy cat, Tiny, to whom the students joyfully respond. We begin by reviewing interview protocols together and testing our recording equipment. Then we engage in a series of questions designed to encourage Ezra to discuss what brought him to Park Slope from Ohio in the 1980s, how the community has changed, his thoughts on changes, and what it is like to run the bookstore.

Interviewing Ezra accomplishes a number of our teaching goals. Aside from modeling the process they will undertake, our conversation with him deepens students’ understanding of history’s impact on individuals. His personal experiences enrich their awareness of how a community’s past informs its present. Bringing students out of school and into the bookstore engages their curiosity. Meeting Ezra and hearing him discuss his life and neighborhood awakens their empathy and develops the historical reasoning skills of understanding multiple perspectives. Finally, their experience of their school’s community becomes more welcoming and expansive. The visit often becomes the first of repeat visits to the store.

Real-World History and Civics

Real-World History and Civics

A UMP school program is a community exploration done in partnership with teachers and students. Each project is custom designed to meet the needs of the specific school, teacher, and class. Teachers and UMP educators collaboratively develop units and lessons around current issues, teacher interests, and the needs of the school. A project might look like a fieldwork and oral history research project in a quickly developing Brooklyn neighborhood, or an examination of the legacy of mid-century urban renewal policies in today’s South Bronx. In addition to writing research papers, students might curate a photography exhibition, a panel discussion, or a presentation of policy memos.

At the end, teachers have a complete curriculum of lesson plans and resources as well as a set of new strategies for maximizing student engagement with the local community, based on real-world history, humanities, and civics. Students end with an argument-based research paper, practice in several research methodologies, a developed set of tools for participating in their local communities, and portfolio pieces to submit to colleges.

Why Oral History?

Oral history has been a foundation of UMP school programming since our beginning. We believe it is a tool with the power and potential to engage students to connect with issues beyond their immediate lives in a highly relevant manner. Many political, economic, and social trends affecting students are presented to them in school on a macro level that feels removed. We believe that to engage students in civic conversation they need to see the direct relevance of these trends on the lives of real people.

Our programs work with young people ages 12-18 who, even if they have lived in one area their whole lives, do not have the same context and perspective that older residents present. We find it continually meaningful and rewarding for students to talk with people who have seen the places where they live change over time. The process allows for a dialogue between the students’ experiences and the lived experience of others.

The interview process elevates student engagement. Students are in charge of preparing for, conducting, and processing the interviews. They choose pieces of an interview to illuminate a story about their communities. This ownership and rigor increase students’ commitment to the process and are reflected in their work products, whether a podcast, an exhibition panel, a video, a blog post, or the basis of research toward a Socratic Seminar or paper.

Methodology

We introduce oral history after students have developed some general background knowledge about the community we are studying. By this point students have gathered and processed information illuminating the complexity of a community’s history and issues through fieldwork involving neighborhood observation and photo documentation walks as well as text research ranging from newspaper articles to research guides by local institutions such as the Brooklyn Historical Society. The students are now ready to grapple with the concept of community stakeholders. Teaching students to conduct and present oral histories is an important process. Through trial and error UMP has developed several methods we reliably implement to engage students in working with interviews. These methods are organized into prepping for, conducting, processing, and presenting oral histories.

Model, Practice, Prep

Modeling how to conduct an interview is a key UMP best practice. We enlist the volunteer services of a long-time community member who can speak to the impacts of community change. This might be a local resident, a parent, or a teacher whom the students are surprised to see in a different capacity. Students observe the UMP educator conduct an oral history and take notes on a worksheet organized into three categories, Information Notes, Question Notes, and Demeanor Notes, (see Classroom Connection: Model Interview Notes Worksheet) to help students critique the process. After observing the interview, students have a Q&A with the interviewee and then a turn-and-talk with peers to discuss observations they made on their charts. We then share as a class about the new neighborhood information we gathered and new research questions that emerged. Together we create a list of interviewing best practices. The debriefing discussion intentionally addresses each of three categories from students’ notetaking sheet in turn to ensure that students have time to process how the use of questions can open up or shut down a conversation, how demeanor and professionalism affect the interview, and how learning someone’s personal story enriches understanding.

Individual, Small Group, and Community Interview Days

After the model interview, we might structure some informal time for students to practice interviewing each other back in the classroom, or we might be ready to move on to students’ conducting oral histories. There are several shapes these interviews can take depending on the project. Sometimes students are engaged in independent neighborhood research. In these cases, they use a structured series of steps to choose an interviewee, develop questions, and conduct their interviews. At other times students and their teacher are engaged in the study of one community. In this case we often organize a Community Interview Day when we invite a number of local residents to the school for a morning or afternoon of concurrent interviewing. A Community Interview Day invites us to partner with local organizations, like the Park Slope Civic Council or Brooklyn Historical Society, which have helped us to organize interviews, bolstering our relationships and resources.

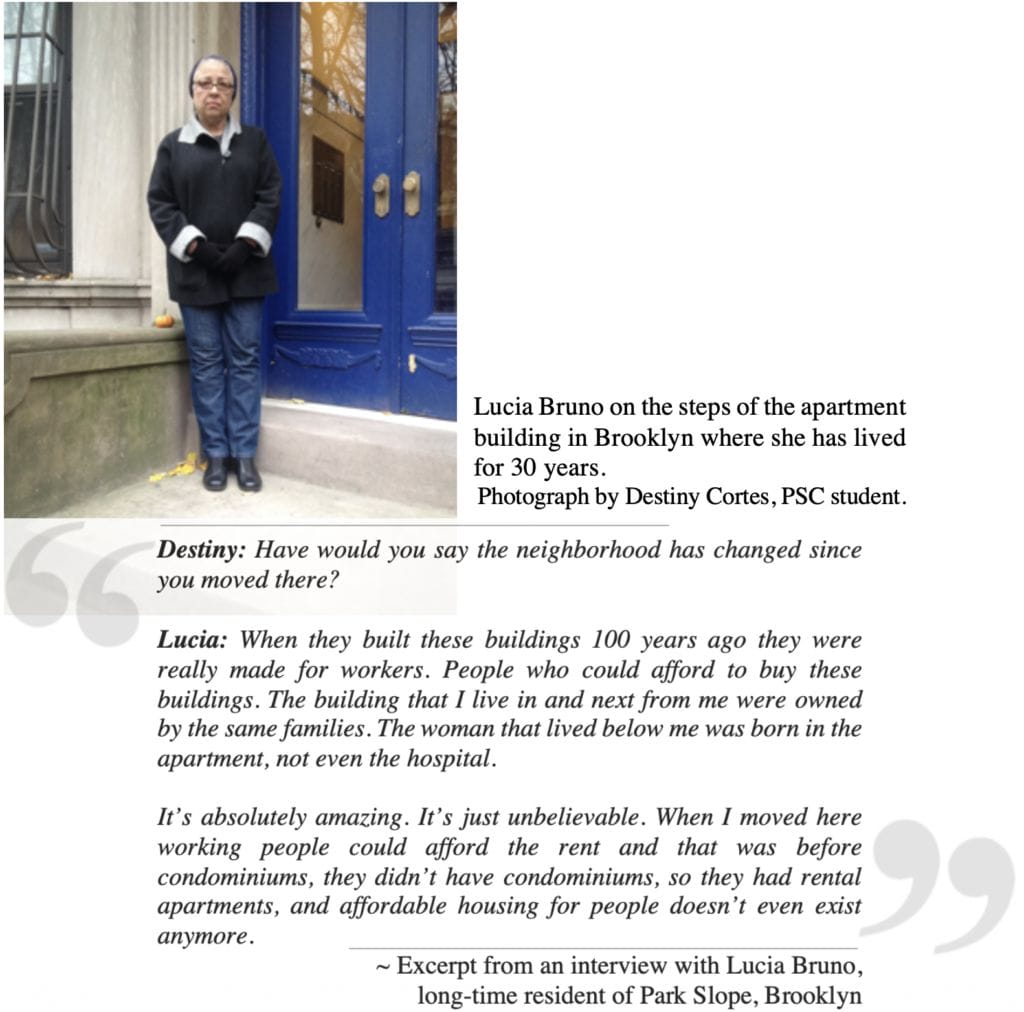

Jeffrey and Carlos interviewing John Cortese during a Community Interview Day at PSC.

Photograph by Rebecca Krucoff.

A general hubbub permeates the teachers’ cafeteria of the John Jay High School campus, a building housing the consortium of four secondary schools that includes PSC. Groups of students cluster at tables of four or five, each engaged in an interview of a long-time neighborhood resident. Adults circulate the edges of the room, observing the process, which is entirely student-led.

To prepare for their Community Interview Day, student groups receive a bio of one interviewee and, referring to our model interview and question prompt lists, together develop and vet a series of questions. They decide who will be the main facilitator, who will be in charge of recording equipment and other logistics such as ensuring that waivers are signed, and who will ask which questions. We work with the school to arrange for a room large enough to host a number of groups at once. We order refreshments for a relaxed mix and mingle when the interviewing ends. After logistics have been accounted for, the actual day feels like magic. Students’ independence in preparing and the event’s formality ascribe a heightened significance, and students take their responsibilities very seriously. Additionally, the act of interviewing a community elder or long-time resident awakens their empathy and curiosity. That each group is engaging with a different person and their story creates a feeling of specialness to the interaction, one that is built on later in class through sharing the experience. Students gain new knowledge and experience the deepening importance of multiple perspectives. History comes alive.

Processing Interviews: Transcribing and Editing

Transcription can be a tedious and challenging task for many of us who use oral history in our work, and students are not immune to this struggle. We combat this fatigue with our students in two ways. First, we frame processing within the context of their final project. Seeing where the work is going and how it contributes to their project creates purpose. Second, we provide time for students to process and transcribe their interviews during class. This takes the pressure off to do this work on their own. Students are given a sanctioned opportunity to have their headphones on in class, which provides its own kind of thrill. It is always enjoyable to see students huddled over their class computers, intently listening and jotting notes with time signatures and keywords.

Teaching students to process interviews is straightforward. We give them a handout with very clear steps to take so that they can move at their own speed. As in the interview modeling, we also model how and why to transcribe by sharing examples of a transcription in process. We use the text of the model interview we did as a class to illustrate how this works We also show students several examples of finished student projects that incorporate oral history so they have concrete ideas of where their interview work could lead.

Sharing Work: Exhibitions, Podcasts, Videos, and More

UMP school programs combine city exploration with action research to broaden students’ community understanding and deepen their connection to the places where they live. This research becomes the basis for students’ interpretations of controversial and complex issues facing their local communities. To end a project, students synthesize their research into formal presentations to share their knowledge and ideas with the larger community. Students’ oral history work becomes integrated into various projects combined with their field documentation and other more traditional text-based research. UMP uses real-world project models for students to present their work. Student projects have included in-school, student-curated, two-dimensional exhibitions of photographs, interviews, and text; podcasts and videos; and policy memos, panel discussions, or Socratic Seminars that construct arguments about what should be preserved or changed in their communities.

Exhibitions

Many projects end in student-curated exhibitions. Students are broken into committees, each with a group leader, to take on one of the exhibition tasks. Students select, edit, organize, and mount the exhibitions themselves with guidance in the form of facilitation by their teachers. Students committees sift through photographs to choose and mount for display, or read through writing pieces and oral histories. At the end of the preparation period we invite the community to visit the exhibition in a celebration at the school.

UMP has had a partnership with PSC since our founding. Over 15 years students have researched the changes affecting their borough through close examination of their own neighborhoods and their school neighborhood. PSC has served as a lab site for UMP’s teaching practices and its students and teachers as active collaborators. With their input and experimentation, we have codified our programming and implemented it at schools across New York City. The school remains committed to the work year after year and students have presented their shifting understandings of their borough through numerous projects, archived both at the school and through UMP’s website. This collection has created an historic record of the recent past to which a continuing cycle of students refers and enriches in a continuous loop of research and documentation.

Podcasts

Technology has dramatically developed in the 15 years since UMP began. Students are often much more tech-savvy than UMP staff are, resulting in new presentation formats. An example is seen in the accessibility of podcasting software for students, which provides them the challenge of synthesizing their interviews into an aural story.

Students Manuel Brito and Franciely Paulino worked with their English Language Learning teacher, Louise Bauso, and Paul Allison, coordinator of the youth writing blog Youth Voices Live, to learn the skills of podcasting. They applied these skills to an oral history presentation for their UMP project, embedded in their senior social studies class. Students used podcasting to capture the recollections of Eduardo Rosario, a long-time Brooklyn resident who has witnessed neighborhood change over many years, asking him questions about the neighborhood’s character, its population, and the effects of gentrification.

At the start of their podcast the students state,

Elevating Teacher and Student Experience

UMP’s programming stems from our experiences teaching in the social studies and humanities disciplines. Our projects encourage students to think historically to become civic actors in today’s world. We incorporate much of the thinking on the forefront of social studies instruction today, specifically the work of the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) and of Bruce Lesh, history teacher and author of Why Don’t You Just Tell us the Answer? Teaching Historical Thinking in Grades 7-12 regarding the teaching of historical thinking skills and historical reasoning. Working with oral histories gives students practice with these tools, specifically regarding the consideration of multiple perspectives, examining continuity and change, and understanding cause and effect. In synthesizing their interviews into larger projects, students must consider their sourcing information and the context in which the speaker is speaking. Seeing the interview as a primary source within a much broader study makes concrete to students the methods that historians use to analyze and interpret history. An additional goal is for our projects to promote college readiness. Engaging in oral history asks students to activate research, develop speaking and listening skills, transcribe, analyze, synthesize and summarize information in formal presentations. These are skills that will transfer to work in various subjects and projects as they move forward with their education.

Finally, the work resonates on a more poetic level. Students get the space to slow down and connect with someone else, a person whom they might not have recognized as a part of their community or to whom they have not listened closely before. This experience opens them up, at least temporarily, to think about someone else’s experience, listen, and empathize. They have an opportunity to recognize history’s dynamism through hearing the experiences of others and, possibly, experience themselves are as part of their neighborhood and their city’s unfolding story.

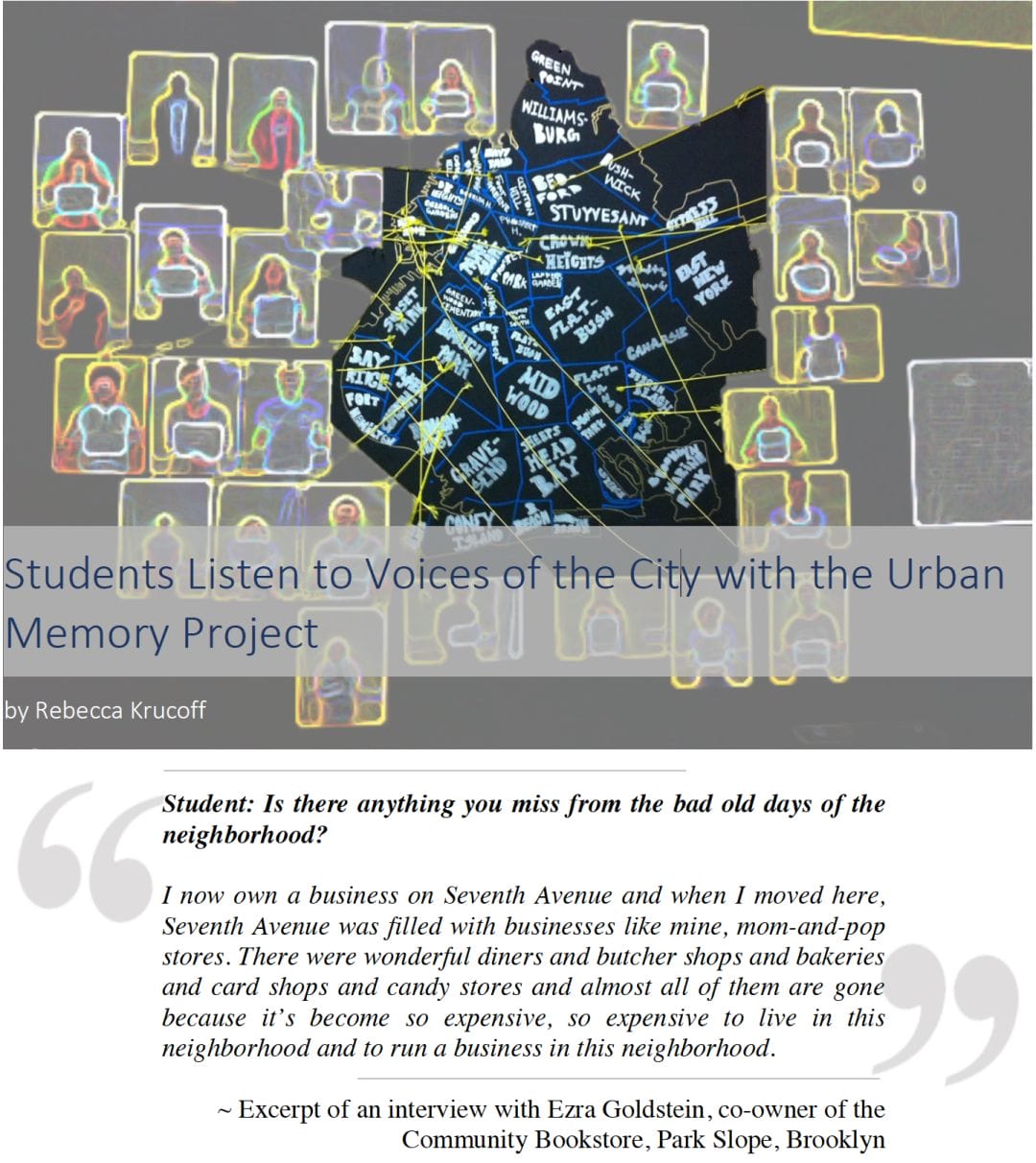

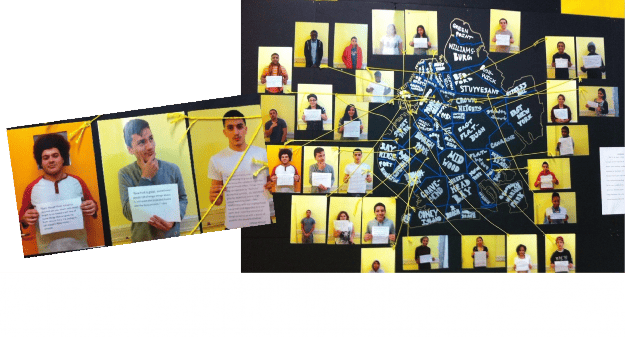

Student-generated map of neighborhoods where classmates live in Brooklyn. Each student

holds an excerpt from an interview they gave to each other about their relationship to Brooklyn.

Photos by Rebecca Krucoff.

Find Model Interview Worksheet that accompanies this article here.

Rebecca Krucoff is a former social studies teacher and museum educator who is on faculty at Pratt Institute where she teaches courses in education, museum education, and public history. She holds an MS.Ed from Bank Street College of Education and an MS Historic Preservation from Pratt Institute. Alongside her teaching and consultancy work, Rebecca is co-founder and director of the Urban Memory Project, an education nonprofit that encourages city residents to explore the vital relationship between their personal history and their city’s history.

Acknowledgements

This article is indebted to the work of the amazing teachers and students of Park Slope Collegiate in Brooklyn, particularly Michael Salak, and Principal Jill Bloomberg, who has championed UMP since its founding. I am grateful as well to the numerous NYC residents who have volunteered their time and stories, allowing us a glimpse into their personal cities.

All photos published with permission of Urban Memory Project, Inc.

URLs

http://www.urbanmemoryproject.org

https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/socratic-seminar

https://www.brooklynhistory.org/research-collections/research-guides

https://parkslopeciviccouncil.org

https://www.brooklynhistory.org

https://www.youthvoices.live/2018/01/10/park-slope-then-and-now

https://www.stenhouse.com/content/why-wont-you-just-tell-us-answer