In this article, I highlight ways I used folklore as a central part of my strategies to raise the critical consciousness of predominantly white preservice teachers by introducing them to multicultural histories, concepts, and knowledges as I prepared them to fulfill licensure requirements and guided them toward developing paradigms of educational equity so they might teach all students in their classrooms effectively.

In the first class discussions of every Education and Multicultural America class each semester, I asked preservice teachers why they wanted to become teachers. The most common response was, “I want to teach just like a teacher I had in _______school. I plan to go back to my community to teach.” As discussions progressed, I asked if there had been students of color in their classrooms. Only rarely did I have students who had had classmates who were students of color and when they did, the students of color were in tiny numbers and marginalized, or were frequently biracial or adopted by white families. Through intentional and unintentional historical traditions of residential segregation, these students had had negligible personal interactions with people of color throughout their lives. Many thought that their familiarity with people of color from television, movies, and social media stereotypes presented them with realistic understandings of communities of color. The stark realities of these preservice teachers’ social limitations made clear where our class discussions of race and educational equity needed to begin. I would need to help students examine their own worldviews and provide windows into the worldviews and experiences of communities of color.

Education is the human process of transferring collaboratively developed repositories of valued cultural knowledges and interpreting them through specified worldviews to new generations. These cultural transfer processes can be implemented by informal or institutionalized means. Teacher education programs offer a sanctioned institutionalized process for preparing new generations of teachers to obtain jobs devoted to transferring cultural knowledge to new generations of students using standardized curriculum and pedagogies. Embedded in those curricula are worldviews that provide lenses for understanding knowledge, interpreting reality, and specifying rules and roles to guide people’s actions and relationships in those things (Koltko-Rivera 2004, 4). To achieve equitable and just education in 21st-century multicultural classrooms, teacher education programs must equip teacher candidates with skills and knowledge that respect and incorporate cultural knowledge, worldviews, and pedagogies from the diverse cultures of their students to teach all students effectively. No worldview based in a singular cultural tradition can adequately reach all students, so teachers must acquire a panoply of tools and skills that work within an multiculturally inclusive and critical worldview to be prepared to engage all students fully. If 21st-century teachers can infuse their curricula and pedagogies with selected resources from folklore and cultural traditions flourishing within their school communities, they may be able to engage their students more deeply, more effectively, and more equitably, as well as learn from their students and their communities.

Conventional American curriculum has been based in the cultural knowledge and worldviews of Anglo American settlers, including ideologies of white racial dominance and white supremacy (Spring 2016, Jay 2003, Kincheloe et al. 2000, King 1991, Sleeter 2001). Since the late 20th century civil rights movements of people of color, women, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ people, schools of education have attempted to become more inclusive by adding some knowledge about diverse racial and ethnic groups into their programs. Yet many teacher education students have not had opportunities to understand how the conventional curriculum excludes, erases, or distorts the stories of people outside the dominant group, nor to examine biases that mainstream culture carries into the classroom (Sleeter 2008). Public school curricula ignore and denigrate multicultural ways of knowing and doing through the use of racial and ethnic stereotypes, distortion of facts and relationships, and incomplete and absent narratives (Loewen 1996, Zinn 1998).

During the last 15 years of my recently completed 30-year teaching career at a predominantly white liberal arts university in the nonurban upper Midwest, I taught several sections of a required undergraduate course to primarily white preservice teachers as a significant part of my teaching load. As an African American professor, trained first as a music educator and later as a folklorist and ethnomusicologist, I taught Education and Multicultural America as a Professor of American Multicultural Studies outside the teacher education program at this university. After our department inherited this marginalized course as a short, superficial overview of the histories of four major racial groups, I redesigned the syllabus to align with the standards required for licensure and to be more directly relevant to students’ understandings of the educational experiences of students of color. My interdisciplinary knowledge and skills as a folklorist as well as critical multicultural knowledges, histories, and traditions were central to developing this course. Although several states mandate that teacher education students acquire some knowledge about the histories and cultures of people of color as well as strategies for teaching students of color, some programs minimize and marginalize this information, limiting it to a single course and rarely reinforcing or extending this knowledge to other teacher education classes within the program. However, I contend that truly successful teacher education programs integrate multicultural knowledges into all courses within teacher education programs to generate an inclusive worldview that broadly prepares future educators to teach inclusively and equitably for all children (Merryfield 2000, Gay and Howard 2000). Currently, and in the foreseeable future, children of color make up the majority of students in public school systems across the nation (Noguera and Akom 2000, Ayers et al. 2008). Minnesota, where I live and teach, is among the states that have been struggling to close longstanding educational opportunity gaps for students of color. One proven strategy for reducing this gap and improving the achievement and academic engagement of children of color has been the intentional incorporation and integration of multicultural knowledges and pedagogies into school curricula (Paris and Alim 2017; Ladson-Billings 1995, 2014; Precious Knowledge 2011).

Throughout this article, I share a variety of resources and tools that can contribute to preparing teachers better to teach equitably by illuminating essential aspects that must be addressed in these courses and offer examples from my course of infusing cultural knowledges to illustrate these points. In each section, I highlight the use of specific genres of folklore in bolded italics throughout the text.

Create a safe and inclusive space for hosting deep discussion. First, I engaged the class in collaboratively setting ground rules for respectful conversation on topics that often uncover deep emotions. Building consensus on ground rules, I next used George Ella Lyon’s poem, “Where I’m From,” an exercise that has become folklore, to help my students become acquainted with each other in structured ways and initiate a semester-long conversation about respect for social and cultural differences. They wrote poems from Lyon’s template, then read their writings to the class. This template offered a no-fail model from which students could create and share personal testimonies about where they were from, no matter their age or background. Through this activity, students discovered that they each have a distinctive voice and to be successful students did not have to do things in the same ways. I used the assignment to bring each student’s voice into the classroom and help them discover commonalities with students whom they saw as different from themselves and with students whom they saw as similar to themselves. Such discoveries highlight the humanity of everyone and help to build safe spaces for deep conversation.

Create a safe and inclusive space for hosting deep discussion. First, I engaged the class in collaboratively setting ground rules for respectful conversation on topics that often uncover deep emotions. Building consensus on ground rules, I next used George Ella Lyon’s poem, “Where I’m From,” an exercise that has become folklore, to help my students become acquainted with each other in structured ways and initiate a semester-long conversation about respect for social and cultural differences. They wrote poems from Lyon’s template, then read their writings to the class. This template offered a no-fail model from which students could create and share personal testimonies about where they were from, no matter their age or background. Through this activity, students discovered that they each have a distinctive voice and to be successful students did not have to do things in the same ways. I used the assignment to bring each student’s voice into the classroom and help them discover commonalities with students whom they saw as different from themselves and with students whom they saw as similar to themselves. Such discoveries highlight the humanity of everyone and help to build safe spaces for deep conversation.

Furthermore, since I was the first African American professor (even the first Black person) whom many students had interacted with, this course challenged many of them in new ways and introduced them to new perspectives and experiences. I worked to expand their limited exposure to the knowledges and experiences of communities of color and created a safe space for them to ask questions in any way they could at first, expecting them to acquire appropriate vocabulary and concepts as the course developed.

Have students examine and reflect on their own social locations and biases. Working at the junction of history, folklore, ethnic studies, multicultural educational praxis, social justice education, and current events, I asked preservice teachers to take a journey with me to explore areas they had not been yet been introduced to, beginning with reflections on their own identities and social locations. Many of the students (overwhelmingly white) had not examined the multiplicity of their identities or reflected upon their experiences of schooling. In assignments throughout the semester, I asked students to examine, reflect, and write about their understandings and personal experiences in light of our topics of study. We discussed the power of socialization to shape social expectations and rules for the roles and social identities we each take. They explored personal experience stories of race, curriculum, and being taught in the classroom. They also reflected on their biases. Students wrote short critical journal reflections about what one key idea from both class and assigned readings for each unit meant for them as a future teacher and for their future students. Through these assignments, I hoped to instill the professional practices of reflection and unpacking biases in their own lives, so that they increased their abilities to interrupt biases and build skills to teach more equitably (Howard 2003, Krummel 2013). Personal narratives from this process also provide interesting insights into aspects of the occupational folklore of teaching, as Merryfield (2000), Au (2009), and Lee et al. (2007) reveal.

Have students examine and reflect on their own social locations and biases. Working at the junction of history, folklore, ethnic studies, multicultural educational praxis, social justice education, and current events, I asked preservice teachers to take a journey with me to explore areas they had not been yet been introduced to, beginning with reflections on their own identities and social locations. Many of the students (overwhelmingly white) had not examined the multiplicity of their identities or reflected upon their experiences of schooling. In assignments throughout the semester, I asked students to examine, reflect, and write about their understandings and personal experiences in light of our topics of study. We discussed the power of socialization to shape social expectations and rules for the roles and social identities we each take. They explored personal experience stories of race, curriculum, and being taught in the classroom. They also reflected on their biases. Students wrote short critical journal reflections about what one key idea from both class and assigned readings for each unit meant for them as a future teacher and for their future students. Through these assignments, I hoped to instill the professional practices of reflection and unpacking biases in their own lives, so that they increased their abilities to interrupt biases and build skills to teach more equitably (Howard 2003, Krummel 2013). Personal narratives from this process also provide interesting insights into aspects of the occupational folklore of teaching, as Merryfield (2000), Au (2009), and Lee et al. (2007) reveal.

Help students discover that not everyone has had access to formal education; in fact, education has operated as a privilege and not a right for everyone. Students read the SEED[1] classic article by Emily Style, “Curriculum as Windows and Mirrors” (1998), asserting that all students should have windows to see and understand realistic images of others and mirrors to see affirming images of themselves and their cultures in their curriculum. After my students realized that many students do not have such opportunities, I set them up to discover that inclusiveness in education is a relatively new idea. Using Segments 2 and 3 of School: The Story of American Public Education (2001) for students to learn the history of education in the 20th century, I challenged them to detect who was absent in this narrative and who did not have full access to education in the 20th century. This series highlighted personal narratives contextualized by history to tell stories tied to civil rights struggles of people of color. The African American struggle for educational civil rights opened paths for other communities of color and marginalized groups such as women, queer people, and people with disabilities to protest for access to education.

Help students discover that not everyone has had access to formal education; in fact, education has operated as a privilege and not a right for everyone. Students read the SEED[1] classic article by Emily Style, “Curriculum as Windows and Mirrors” (1998), asserting that all students should have windows to see and understand realistic images of others and mirrors to see affirming images of themselves and their cultures in their curriculum. After my students realized that many students do not have such opportunities, I set them up to discover that inclusiveness in education is a relatively new idea. Using Segments 2 and 3 of School: The Story of American Public Education (2001) for students to learn the history of education in the 20th century, I challenged them to detect who was absent in this narrative and who did not have full access to education in the 20th century. This series highlighted personal narratives contextualized by history to tell stories tied to civil rights struggles of people of color. The African American struggle for educational civil rights opened paths for other communities of color and marginalized groups such as women, queer people, and people with disabilities to protest for access to education.

Multicultural education as a discipline emerged to address the concerns expressed by each of the 1930s-1970s civil rights movements of African Americans, American Indians, Mexican Americans, and Asian Americans. These movements demanded educational reforms to move toward equity for the benefit of children from their communities. Each sought to have:

- Teachers who are practitioners of the worldviews of their students and their communities who could be role models and mentors hired in their schools;

- Accurate representations of their cultures to replace derogatory, denigrating, and distorted histories and images of their communities in the curriculum;

- Pedagogical transformations based in cultural intellectual frameworks to replace often ineffective and culturally damaging teaching strategies used to interact with and instruct students;

- An end to corporal and humiliating punishments for students of color;

- An end to practices of segregation that left these communities with inequitably resourced schools;

- The right for groups to control and self-determine educational choices and curricula to fit the needs of their communities;

- Bilingual education for all students;

- Accurate and inclusive histories incorporating multicultural knowledges, histories, and perspectives in all courses;

- Incorporation of pedagogies and ways of interacting based in the knowledges and educational practices of communities of color to facilitate the learning of their children;

- A commitment by educators to the belief that ALL children have the capacity learn and succeed; and

- Access to a liberal arts education and college preparation (Spring 2016; Lopez 2008).

Nationwide, many schools have not yet consistently met these demands to positively educate students of color.

Destabilize the assuredness in what students assume they know and instill an understanding that learning is a lifelong process and there is so much more to learn. Many students, both white and of color, came to the course with assumptions of the unimportance of the subject matter, because it was not placed centrally in their curriculum and it was about people whom they had been taught to marginalize. I needed to challenge these ideas that underpinned what they thought they knew. First, I declared that through schooling, they had been exposed to a single system of knowledge and asserted that there were other systems of knowledge never touched by conventional schooling, citing indigenous knowledges from around the world and other world cultures rarely addressed in their educational experience. Then, using Library of Congress Knowledge Cards for African Americans and African American women to illustrate this point, I broke them into small groups, followed by large group discussion, and introduced them to accomplished people of color (not celebrities) who were absent from their curriculum. The first round addressed outstanding African Americans in general, while the second featured stellar Black women. Usually, students had never heard of any of these people and had certainly never previously learned anything about any of the more than 50 Black women. When they expressed shock and questioned the absence of these people from their prior curricula, I asserted that this absence was also the case with Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinx people (An 2016). Then I revealed the constructed nature of their curriculum as a social, political framework that reflected societal biases and left out people from groups marginalized by hierarchies of race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and ability (McIntosh 1998).

Destabilize the assuredness in what students assume they know and instill an understanding that learning is a lifelong process and there is so much more to learn. Many students, both white and of color, came to the course with assumptions of the unimportance of the subject matter, because it was not placed centrally in their curriculum and it was about people whom they had been taught to marginalize. I needed to challenge these ideas that underpinned what they thought they knew. First, I declared that through schooling, they had been exposed to a single system of knowledge and asserted that there were other systems of knowledge never touched by conventional schooling, citing indigenous knowledges from around the world and other world cultures rarely addressed in their educational experience. Then, using Library of Congress Knowledge Cards for African Americans and African American women to illustrate this point, I broke them into small groups, followed by large group discussion, and introduced them to accomplished people of color (not celebrities) who were absent from their curriculum. The first round addressed outstanding African Americans in general, while the second featured stellar Black women. Usually, students had never heard of any of these people and had certainly never previously learned anything about any of the more than 50 Black women. When they expressed shock and questioned the absence of these people from their prior curricula, I asserted that this absence was also the case with Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinx people (An 2016). Then I revealed the constructed nature of their curriculum as a social, political framework that reflected societal biases and left out people from groups marginalized by hierarchies of race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and ability (McIntosh 1998).

Furthermore, we discussed how many stories that students have learned previously have been incomplete or inaccurate (Loewen 1996). We revisited the legends of Columbus, Pocahontas, and the U.S.-Dakota War (1862) taught in schools and public media, comparing them with historical scholarship and the oral histories of communities of color. Once again, students were shocked at the ways their prior curricula had distorted historical facts.

Build new transformative frameworks that move students toward skills for equity and begin with the assumption that students of color carry cultural knowledges and worldviews that can be employed as assets in the classroom. After introducing multicultural education as a response to the demands of civil rights movements, we defined the term and examined several theoretical frameworks designed to achieve equity in multicultural education. Banks (1995) identified five dimensions of multicultural education: content integration, knowledge construction, equity pedagogy, prejudice reduction, and empowering school culture. These dimensions require that educators acquire critically responsive analyses so that all students can be provided equitable opportunities to achieve their full potential and to function accountably in a multicultural and global world (Gorski 2010). The skills and knowledge of folklorists can help teacher education programs draw on the diverse cultural knowledges and worldviews of school communities to implement Banks’ five dimensions and to facilitate needed paradigm shifts for preservice teachers, especially in the areas of content integration, knowledge construction, equity pedagogy. and prejudice reduction. Numerous scholars emphasize the centrality of embracing and respecting the diversities of cultural knowledges and frameworks brought by students and their families in schools (Woodson 1933; Banks 1995, 2013; Banks and Banks 1995; McIntosh 1998; Nieto 2000; Yosso 2002). Deafenbaugh (2015) highlights the relationships that can be built with larger communities, if schools can embrace the diverse cultural traditions coming through their doors and underscores the fifth dimension mentioned by Banks, empowering school culture.

Build new transformative frameworks that move students toward skills for equity and begin with the assumption that students of color carry cultural knowledges and worldviews that can be employed as assets in the classroom. After introducing multicultural education as a response to the demands of civil rights movements, we defined the term and examined several theoretical frameworks designed to achieve equity in multicultural education. Banks (1995) identified five dimensions of multicultural education: content integration, knowledge construction, equity pedagogy, prejudice reduction, and empowering school culture. These dimensions require that educators acquire critically responsive analyses so that all students can be provided equitable opportunities to achieve their full potential and to function accountably in a multicultural and global world (Gorski 2010). The skills and knowledge of folklorists can help teacher education programs draw on the diverse cultural knowledges and worldviews of school communities to implement Banks’ five dimensions and to facilitate needed paradigm shifts for preservice teachers, especially in the areas of content integration, knowledge construction, equity pedagogy. and prejudice reduction. Numerous scholars emphasize the centrality of embracing and respecting the diversities of cultural knowledges and frameworks brought by students and their families in schools (Woodson 1933; Banks 1995, 2013; Banks and Banks 1995; McIntosh 1998; Nieto 2000; Yosso 2002). Deafenbaugh (2015) highlights the relationships that can be built with larger communities, if schools can embrace the diverse cultural traditions coming through their doors and underscores the fifth dimension mentioned by Banks, empowering school culture.

Center the voices and experiences of both educators of color and communities of color to tell their experiences of schooling based on personal narratives. Using interdisciplinary perspectives, I prioritized the voices of communities of color who not only shared their scholarship on education but also their experiences with mainstream educational systems. By ensuring that members from communities of color told their own personal narratives and histories, I featured voices from these communities in the course. As a result of decentering and critiquing mainstream narratives about people of color, students were able to view the histories and experiences of these communities in their fullness. Such an approach centers the narratives of communities of color toward equity (Nieto 2002), an idea that is not new to folkloristics.

Center the voices and experiences of both educators of color and communities of color to tell their experiences of schooling based on personal narratives. Using interdisciplinary perspectives, I prioritized the voices of communities of color who not only shared their scholarship on education but also their experiences with mainstream educational systems. By ensuring that members from communities of color told their own personal narratives and histories, I featured voices from these communities in the course. As a result of decentering and critiquing mainstream narratives about people of color, students were able to view the histories and experiences of these communities in their fullness. Such an approach centers the narratives of communities of color toward equity (Nieto 2002), an idea that is not new to folkloristics.

In addition, two texts for the class, Beyond Heroes and Holidays (Lee et al. 2007), and Rethinking Multicultural Education: Teaching for Equity and Cultural Justice (Au 2014) provided a plethora of narratives of teachers sharing their teaching successes and challenges across a variety of subjects and grade levels as they attempted to implement strategies to teach equitably. Using personal narratives of classroom teachers reflecting on their efforts to implement pedagogies that are inclusive and equitable in their classrooms is an important aspect of teachers’ occupational folklore. These teaching stories have been an important tool for helping students understand the power and possibilities of equitable teaching and offering insights into teaching from multiple cultural perspectives.

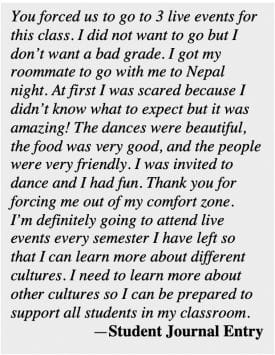

Have students participate in experiential learning to reinforce what they are reading, writing about, and discussing in class. By exposing students to cultural narratives and ways of being that have been absent from their curriculum, I reinforced and expanded their experiences in the world in multiple ways. I required students to attend, analyze, and write about curated opportunities that helped students apply their knowledge and strengthen their use of new interpretive frameworks (see Phillion et al. 2005).

Have students participate in experiential learning to reinforce what they are reading, writing about, and discussing in class. By exposing students to cultural narratives and ways of being that have been absent from their curriculum, I reinforced and expanded their experiences in the world in multiple ways. I required students to attend, analyze, and write about curated opportunities that helped students apply their knowledge and strengthen their use of new interpretive frameworks (see Phillion et al. 2005).  I used videos, guest visitors, participation in live events, trips to museums, and stories from their own lives to bring home the readings and cultural values and practices of the communities they were studying in class. Through public folklore and arts programming students opened their hearts and minds to expressive cultures other than their own. Students repeatedly stated that these exposures made a lasting impact on them. For students with little prior exposure to cultures different from their own, these opportunities provided safe ways to learn about, interrogate, and interact with others, increasing their knowledge of the world (Bowman and Hamer 2011). Students expanded their comfort zones by trying diverse foods, viewing arts from many cultures, hearing music, and experiencing languages, stories, theatre, and rituals from people of color, and meeting students and people of color living here from all over the world. Experiential and participatory components such as the regional pow-wow or a local las posadas celebration enriched student understanding of other cultural worldviews within the community where they live.

I used videos, guest visitors, participation in live events, trips to museums, and stories from their own lives to bring home the readings and cultural values and practices of the communities they were studying in class. Through public folklore and arts programming students opened their hearts and minds to expressive cultures other than their own. Students repeatedly stated that these exposures made a lasting impact on them. For students with little prior exposure to cultures different from their own, these opportunities provided safe ways to learn about, interrogate, and interact with others, increasing their knowledge of the world (Bowman and Hamer 2011). Students expanded their comfort zones by trying diverse foods, viewing arts from many cultures, hearing music, and experiencing languages, stories, theatre, and rituals from people of color, and meeting students and people of color living here from all over the world. Experiential and participatory components such as the regional pow-wow or a local las posadas celebration enriched student understanding of other cultural worldviews within the community where they live.

Shifting paradigms is a developmental process (not a checklist) that requires continuous effort for growth. Allow processing time and time for maturation through discussion, reflection, journaling, questioning, and written assignments that require students to deliberate and apply new information throughout the course. Students find collaborative conversations particularly generative in the growth process. Students who push back tend to be wrestling with ideas, while those who are overwhelmed may shut down and can give up, so it is important to monitor continuously where your students are in their processing and offer several avenues for them to process these ideas.

Shifting paradigms is a developmental process (not a checklist) that requires continuous effort for growth. Allow processing time and time for maturation through discussion, reflection, journaling, questioning, and written assignments that require students to deliberate and apply new information throughout the course. Students find collaborative conversations particularly generative in the growth process. Students who push back tend to be wrestling with ideas, while those who are overwhelmed may shut down and can give up, so it is important to monitor continuously where your students are in their processing and offer several avenues for them to process these ideas.

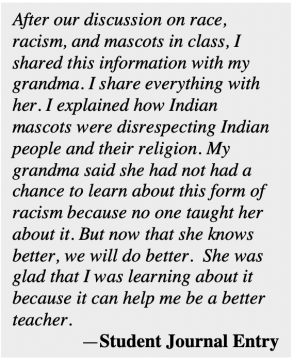

Interrogate the concept of race and racism and how it shapes perception, opportunities, and reality in life and schools. In asking the question, “What is race?,” students learned of the power of rumor, prejudice, and beliefs. Few knew what race really was, even though they had assumptions tied to the word. We examined definitions, structure, and characteristics of race and racism. Students were shocked to learn that race is an arbitrary category not based in biology and is instead a sociopolitical construct designed to do the work of constructing inequality in our society. I defined race as a concept that uses group social power and sanction to construct inequalities by regulating one group to have access to resources and opportunities at the expense of others. In addition, we explored some of the complexities of racial categories as a way that communities have come to identify themselves, under duress.

Interrogate the concept of race and racism and how it shapes perception, opportunities, and reality in life and schools. In asking the question, “What is race?,” students learned of the power of rumor, prejudice, and beliefs. Few knew what race really was, even though they had assumptions tied to the word. We examined definitions, structure, and characteristics of race and racism. Students were shocked to learn that race is an arbitrary category not based in biology and is instead a sociopolitical construct designed to do the work of constructing inequality in our society. I defined race as a concept that uses group social power and sanction to construct inequalities by regulating one group to have access to resources and opportunities at the expense of others. In addition, we explored some of the complexities of racial categories as a way that communities have come to identify themselves, under duress.

The dynamic processes that continually construct systemic and pervasive inequalities (the work) are the processes of racism. I differentiated those processes from prejudice and discrimination and investigated racism’s properties as a dynamic system of oppression based in the hierarchical power and privilege of a dominant group who exerts power over other groups directly and systemically through policies and practices. As we explored the educational histories of each racial group, students learned about the strategies each group faced in its encounter with U.S. educational systems and how these were historically and intentionally implemented systemically to produce inequitable experiences for students of color. Whites implemented racism in schools through laws, policies, pedagogy, curriculum, and practices of segregation, stereotyping, distortion, silencing, forced absence from curriculum, disparate discipline/violence practices, and incarceration—all of which denied students of color access to educational and societal resources and opportunities. These inequities continue to have persistent legacies and consequences in the present, of which most of these preservice teachers were generally unaware.

Finally, we used the video True Colors (1991) and a classic article on white privilege (McIntosh 1998) to raise preservice teachers’ awareness of their own socialization into a racialized worldview. Through vigorous discussion, students affirmed that the video still spoke to traditions of discrimination and oppression that persist in our society. Part of the needed paradigm shift is to make this invisible information, visible to them, so it becomes something that they understand that they as teachers have power to change (May-Machunda 2013).

Equip students with tools to begin applying critical analysis. Folkloristics has not yet fully interrogated how racism employs traditional cultural beliefs and practices to operate as a system of oppression in American society, but it has tools and a history of exploring questions of identity, community representation, and worldviews that would be useful in taking on such an examination.

Equip students with tools to begin applying critical analysis. Folkloristics has not yet fully interrogated how racism employs traditional cultural beliefs and practices to operate as a system of oppression in American society, but it has tools and a history of exploring questions of identity, community representation, and worldviews that would be useful in taking on such an examination.

In the African American unit of the course, students explored the power of stereotypes to misrepresent groups and convey ideologies of racial inequality through Marlon Riggs’ acclaimed documentary Ethnic Notions (1987). This film guided students to understand the power of racial ideologies to misrepresent groups through beliefs in the inferiority of nonwhite peoples, the use of stereotypes, and naming practices of individuals and groups, lessons that extended to each of the other racial groups (Jo 2004, Pewewardy 2004). Students saw the enactment of those beliefs in the intentional construction of legal barriers and segregation that also affected the other groups. They saw the use of incarceration and connected it to the school-to-prison pipeline, beginning in preschool. The unit also deconstructed the stereotype that African Americans have not been interested in attaining education by examining persistent African American attempts to attain education from slavery to Reconstruction to the present.

The Latinx and the Asian American units emphasized linguistic oppression and persistent, unfair immigration restrictions. The toll of hostilities to heritage language speakers on learning and the precarity of immigrant families have severely affected educational experiences for students in classrooms across the country. For example, we explored the meanings of Puerto Rican music, dance, and casitas as they affirmed identities and transnational connections. We also used the video Precious Knowledge (2011) to highlight challenges to transforming curricula in the present time, and to show traditions in context, such as a Day of the Dead ritual for immigrants who had died while crossing the desert.

An equitable worldview for the classroom must strive for educational justice. How the struggle for educational justice is framed and presented is key to moving teachers to teach for equity. Many stories about people of color in the curriculum have been narratives of dominance, one-sided, incomplete, and characterizing people of color as incapable and deficient. An equitable story must present counternarratives that take into account complexities, multiple sides, and systemic power relations and contribute to fuller fact-filled interpretations of events. For example, the narratives about the civil rights struggles for education are not merely about victimization by injustice. They are also stories of persistent resistance to oppression, resilience, and struggles for justice. Educators need to know and tell fuller stories, with their complexities, to make sense and connect to other contextual information students have already learned. Students need to know that success in these struggles involved lots of people participating in multiple struggles, not just a leader. Furthermore, students also need to understand that after achieving success in a movement, oppression demands backlash by the dominant group to try to control and limit advancement of the targeted group.

An equitable worldview for the classroom must strive for educational justice. How the struggle for educational justice is framed and presented is key to moving teachers to teach for equity. Many stories about people of color in the curriculum have been narratives of dominance, one-sided, incomplete, and characterizing people of color as incapable and deficient. An equitable story must present counternarratives that take into account complexities, multiple sides, and systemic power relations and contribute to fuller fact-filled interpretations of events. For example, the narratives about the civil rights struggles for education are not merely about victimization by injustice. They are also stories of persistent resistance to oppression, resilience, and struggles for justice. Educators need to know and tell fuller stories, with their complexities, to make sense and connect to other contextual information students have already learned. Students need to know that success in these struggles involved lots of people participating in multiple struggles, not just a leader. Furthermore, students also need to understand that after achieving success in a movement, oppression demands backlash by the dominant group to try to control and limit advancement of the targeted group.

Present students with the knowledge of allies and their roles as heroes. Some whites put their lives on the line to assist communities of color in their civil rights struggles. Stories of white allies following the leadership of communities of color provide dominant group models of standing against injustice in systems of oppression (Tatum 1994). Those stories should be part of the curriculum to provide alternative examples to accepting and promoting injustice.

Present students with the knowledge of allies and their roles as heroes. Some whites put their lives on the line to assist communities of color in their civil rights struggles. Stories of white allies following the leadership of communities of color provide dominant group models of standing against injustice in systems of oppression (Tatum 1994). Those stories should be part of the curriculum to provide alternative examples to accepting and promoting injustice.

Also, communities of color have often supported each other as allies across racial boundaries. These stories contest stereotypes of communities of color only conflicting with each other. The short video Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children/Para todos los niños (2002) illustrates how Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP as well as other cultures’ civil rights organizations helped Mexican Americans fight the segregation of Mexican American schools and highlighted how the Mexican American Mendez family protected the property of an interred Japanese family.

Structure classes and assignments to help students see worldviews other than their own and the power of communities to resist the oppression of racism. After providing a framework for understanding Native American educational experiences and discussing boarding school experiences during the period of Allotment and Attempted Assimilation, I used parts of three episodes of the video Ojibwe: Waasa Inaabidaa (2002) to examine Anishinaabe educational experiences and cultural frameworks. Boarding school attendees shared personal narratives of boarding school experiences in contrast with culturally based tribal education programs on many reservations today. After viewing these episodes, I asked students to identify and compare/contrast characteristics of the cultural frameworks for education of the Anishinaabe with their own Western educational experiences. Many students reflected on the competitive, individualistic, often punitive, and inflexible mandatory educational system that they experienced, and found it less appealing than many aspects of Indigenous approaches to education that were cooperative, collaborative, affirming, student directed, and growth centered. The goal of this discussion was to emphasize the disparate nature of Indigenous worldviews of education in contrast to the American worldview of public schooling and awaken future teachers to the profound culture shock (intensified by institutionalized white supremacy) Native students would have encountered whenever they were forced into Western systems of education.

Structure classes and assignments to help students see worldviews other than their own and the power of communities to resist the oppression of racism. After providing a framework for understanding Native American educational experiences and discussing boarding school experiences during the period of Allotment and Attempted Assimilation, I used parts of three episodes of the video Ojibwe: Waasa Inaabidaa (2002) to examine Anishinaabe educational experiences and cultural frameworks. Boarding school attendees shared personal narratives of boarding school experiences in contrast with culturally based tribal education programs on many reservations today. After viewing these episodes, I asked students to identify and compare/contrast characteristics of the cultural frameworks for education of the Anishinaabe with their own Western educational experiences. Many students reflected on the competitive, individualistic, often punitive, and inflexible mandatory educational system that they experienced, and found it less appealing than many aspects of Indigenous approaches to education that were cooperative, collaborative, affirming, student directed, and growth centered. The goal of this discussion was to emphasize the disparate nature of Indigenous worldviews of education in contrast to the American worldview of public schooling and awaken future teachers to the profound culture shock (intensified by institutionalized white supremacy) Native students would have encountered whenever they were forced into Western systems of education.

Have students envision what equitable and inclusive classrooms and schools would look like. What would be needed for them as teachers to succeed in having schools fully serving all students? What should be in place? This was the question for the final exam for the course. By the end of the course, preservice teachers had learned how critical it is to build relationships with all students in their classrooms and their families, based in the beliefs that all children can learn and that cultural knowledges are assets. They also recognized how racism shaped and harmed the education of all children, particularly children of color, but they also realized that there is a need to disrupt that process actively. They can even envision what an equitable school and classroom might look like and can acknowledge in what ways they personally needed to grow to have the skills achieve that goal and to serve all students.

Have students envision what equitable and inclusive classrooms and schools would look like. What would be needed for them as teachers to succeed in having schools fully serving all students? What should be in place? This was the question for the final exam for the course. By the end of the course, preservice teachers had learned how critical it is to build relationships with all students in their classrooms and their families, based in the beliefs that all children can learn and that cultural knowledges are assets. They also recognized how racism shaped and harmed the education of all children, particularly children of color, but they also realized that there is a need to disrupt that process actively. They can even envision what an equitable school and classroom might look like and can acknowledge in what ways they personally needed to grow to have the skills achieve that goal and to serve all students.

∾∾∾

More than 50 years after communities of color made assertions about the need for equitable education through their civil rights movements, schools and teacher education programs have barely implemented these demands and have scarcely attempted to explore the strategies laid out by these movements. Current public school systems seem to struggle in their efforts to envision and implement equitable schools that incorporate cultural knowledges to serve their student populations, as documented in the historic and continuing disparate educational success rates of many communities of color (Meatta 2019; Kozol 2012).

To make lasting change toward equity, future teachers will need to be able to envision and then implement new ways of relating to their students and their communities. They will also need to use more representative, culturally responsive, and affirming curriculum to make positive differences for students to engage and complete school successfully and minimize performance disparities (Ladson-Billings 2014,1995; Paris and Alim 2017).

Infusion of folklore content and methodologies can be central in the content integration and knowledge construction phases of building culturally responsive multicultural education (Bowman 2006). Diverse worldviews and ways of doing things are fundamental to equity pedagogy and prejudice reduction. Through infusion of worldviews, narrative, performing traditions, material culture, belief, language, ways of teaching, and other aspects of folklore and history from multiple cultures, teacher education programs can help preservice teachers make the paradigm shifts necessary to begin the intentional processes of transforming curriculum and teaching praxis for the benefit of equitable educational experiences for future generations.

Phyllis M. May-Machunda is a folklorist whose research interests include multicultural education and folklore; African American folklore and music traditions, particularly emphasizing the performance and play traditions of African American women and children; disability studies; and social justice education. She earned her MA and PhD in Folklore and Ethnomusicology from Indiana University and is a new Professor Emerita of American Multicultural Studies at Minnesota State University Moorhead.

URLs

http://www.georgeellalyon.com/where.html

https://www.loc.gov/publish/general/catalog/knowledgecards.html

Works Cited

An, Sohyun. 2016. Asian Americans in American History: An AsianCrit Perspective on Asian American Inclusion in State U.S. History Curriculum Standards. Theory & Research in Social Education. 44.2:244-76.

Au, Wayne. 2009. Rethinking Multicultural Education: Teaching for Racial and Cultural Justice. Portland, OR: Rethinking Schools.

Ayers, William, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Gregory Michie, and Pedro A. Noguera. 2008. City Kids, City Schools: More Reports from the Front Row. New York: The New Press.

Banks, Cherry A. McGee and James A. Banks. 1995. Equity Pedagogy: An Essential Component of Multicultural Education. Theory into Practice. 34.3:152-58.

Banks, James A. 1995. Multicultural Education and Curriculum Transformation. The Journal of Negro Education. 64.4:390-400.

Banks, James A. 2013. The Construction and Historical Development of Multicultural Education, 1962–2012. Theory Into Practice. 52.1:73-82.

Bowman, Paddy B. 2006. Standing at the Crossroads of Folklore and Education. Journal of American Folklore. 119.4:66-79.

Bowman, Paddy B. and Lynne Hamer. 2011. Through the Schoolhouse Door: Folklore, Community, and Curriculum. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Deafenbaugh, Linda. 2015. Folklife Education: A Warm Welcome Schools Extend to Communities. Journal of Folklore and Education. 2:76-83, https://www.locallearningnetwork.org/journal-of-folklore-and-education/current-and-past-issues/jfe-volume-2.

Ethnic Notions. DVD. 1987. Directed by Marlon Riggs. California Newsreel.

Gay, Geneva and Tyrone C. Howard. 2000. Multicultural Teacher Education for the 21st Century. The Teacher Educator. 36/1:1-16.

Gorski, Paul. 2010. Working Definition: The Challenge of Defining “Multicultural Education,” http://www.edchange.org.

Howard, Tyrone C. 2003. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Ingredients for Critical Teacher Reflection. Theory Into Practice. 42.3:195-202.

Jay, Michelle. 2003. Critical Race Theory, Multicultural Education, and the Hidden Curriculum of Hegemony. Multicultural Perspectives.5.4:3-9.

Jo, Ji-Yeon O. 2004. Neglected Voices in the Multicultural America: Asian American Racial Politics and Its Implication for Multicultural Education. Multicultural Perspectives. 6.1:19-25.

Kincheloe, Joe L., Shirley R. Steinberg, Nelson M. Rodriguez, and Ronald E. Chennault. 2000. White Reign: Deploying Whiteness in America. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

King, Joyce E. 1991. Dysconscious Racism: Ideology, Identity, and the Miseducation of Teachers. The Journal of Negro Education. 60.2:133-46.

Koltko-Rivera, Mark E. 2004. The Psychology of Worldviews. Review of General Psychology. 8.1:3-58.

Kozol, Jonathan. 2012. Savage Inequalities: Children in America’s Schools. New York: Broadway Books.

Krummel, Anni. 2013. Multicultural Teaching Models to Educate Pre-service Teachers: Reflections, Service-Learning, and Mentoring. Current Issues in Education. 16.1.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 2014. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the Remix. Harvard Educational Review. 84.1:74-84.

Ladson‐Billings, Gloria. 1995. But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Theory Into Practice. 34.3:159-65.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria and William F. Tate. 2016. Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education. In Critical Race Theory in Education: All God’s Children Gotta Song, eds. Adrienne Dixson and Cecelia K. Rousseau. New York: Routledge, 10-31.

Lee, Enid, Deborah Menkart, and Margo Okazawa-Rey, eds. 2007. Beyond Heroes and Holidays: A Practical Guide To K-12 Multicultural Education, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Teaching for Change.

Loewen, James. 1996. Lies My Teacher Told Me. New York: Touchstone.

López, Nancy. 2008. Antiracist Pedagogy and Empowerment in a Bilingual Classroom in the U.S., circa 2006. Theory into Practice. 47 (1): 43-50.

May-Machunda, Phyllis M. 2013. Moving from the Margins to Intersections: Using Race as a Lens for Conversations about Oppression and Resistance. In Talking about Race: Alleviating the Fear, eds. Steven Grineski, Julie Landsman, and Robert Simmons. Sterling, VA: Stylus Press, 267-73.

McIntosh, Peggy. 1998. Interactive Phases of Curricular and Personal Re-vision with Regard to Race. In Seeding the Process of Multicultural Education: An Anthology, eds. Cathy L. Nelson and Kim A. Wilson. St. Paul: Minnesota Inclusiveness Program, 166-88.

Meatta, Kevin 2019. Still Separate, Still Unequal: Teaching about School Segregation and Educational Inequality. New York Times, May 2. Accessed August 28, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/02/learning/lesson-plans/still-separate-still-unequal-teaching-about-school-segregation-and-educational-inequality.html.

Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children/Para todos los niños. DVD. 2002. Directed by Sandra Robbie. Huntington Beach, CA: KOCE-TV.

Merryfield, Merry M. 2000. Why Aren’t Teachers Being Prepared to Teach for Diversity, Equity, and Global Interconnectedness? A Study of Lived Experiences in the Making of Multicultural and Global Educators. Teaching and Teacher Education. 16.4:429-43.

Nieto, Sonia. 2000. Placing Equity Front and Center: Some Thoughts on Transforming Teacher Education for a New Century. Journal of Teacher Education. 51.3:180-87.

Noguera, Pedro and Antwi Akom. 2000. Disparities Demystified. The Nation. 270.22:29-31.

Ojibwe: Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions. DVD. 2002. Directed by Lorraine Norrgard et al. Duluth: WDSE-TV.

Paris, Django and H. Samy Alim, eds. 2017. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. New York: Teachers College Press.

Pewewardy, Cornel D. 2004. Playing Indian at Halftime: The Controversy over American Indian Mascots, Logos, and Nicknames in School-Related Events. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas. 77.5:180-85.

Phillion, JoAnn, Ming Fang He, and F. Michael Connelly. 2005. Narrative and Experience in Multicultural Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Precious Knowledge. DVD. 2011. Directed by Ari Palos and Erin McGinnis. Dos Vatos Productions.

School: The Story of American Public Education. DVD. 2014. Directed by Sarah Mondale. Films for the Humanities & Sciences. Los Angeles: Stone Lantern Films, distributed by KCET Public Television.

Sleeter, Christine E. 2008. Preparing White Teachers for Diverse Students. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, eds. Marilyn Cochran-Smith, Sharon Feiman-Nemser, D. John McIntyre, and Kelly E. Demers. Routledge Handbooks Online. doi.10.4324/9780203938690.ch32

Sleeter, Christine E. 2001. Preparing Teachers for Culturally Diverse Schools: Research and the Overwhelming Presence of Whiteness. Journal of Teacher Education. 52.2:94-106.

Spring, Joel. 2016. Deculturalization and the Struggle for Equality: A Brief History of the Education of Dominated Cultures in the United States, 8th ed. New York: Routledge.

Style, Emily. 1998. Curriculum as Windows and Mirrors. In Seeding the Process of Multicultural Education: An Anthology, eds. Cathy L. Nelson and Kim A. Wilson. St. Paul: Minnesota Inclusiveness Program, 149-56.

Tatum, Beverly Daniel. 1994. Teaching White Students about Racism: The Search for White Allies and the Restoration of Hope. Teachers College Record. 95.4:463-76.

True Colors. 1991. Diane Sawyer, ABC-Prime Time Live.

Woodson, Carter G. 1933. The Miseducation of the Negro. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers.

Yosso, Tara J. 2002. Toward a Critical Race Curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education. 35.2:93-107.

Zinn, Howard, and Matt Damon. 1998. A People’s History of the United States, 1492-Present. New York: New Press.

[1] SEED (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity) Project is a national teacher training program that partners with schools, organizations, and communities to develop leaders who guide their peers in conversational communities to drive personal, organizational, and societal change toward social justice.