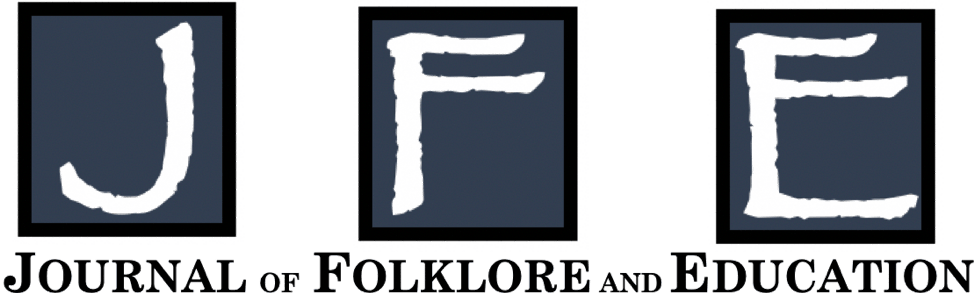

Mural by Haus of Lacks and the Collective GSO. All images courtesy of Greensboro History Museum.

Creative arts born of protest, in the context of a museum exhibition, can instruct and inspire students by expanding notions of what art is and what it can do. The multimedia creations within the Greensboro History Museum’s exhibition Pieces of Now: Murals, Masks, Community Stories and Conversations are both expressive individual artworks and social acts. They show how a single voice and vision can connect to larger communities and historical moments in ways that make a difference and lend agency, especially when museum and school staff listen to those voices.

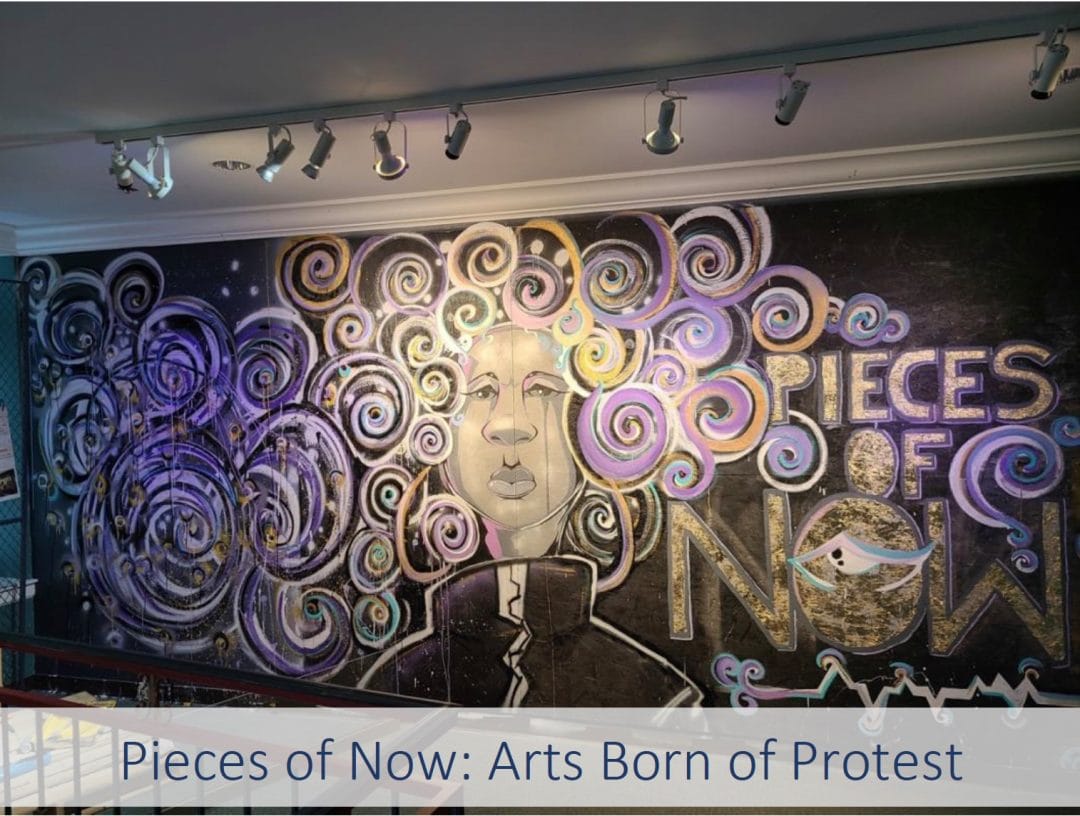

In Greensboro, North Carolina, as in many cities throughout the country, the murder of George Floyd moved many community members to respond publicly. Protests in the streets of downtown, subsequent looting, and protective boarding of windows of businesses were quickly followed by the coming together of artists, protestors, and business owners to create an expansive city-space of community voices. The public art murals created on the window boards, sidewalks, and streets, as well as the associated videos and social media, connected diverse communities in the city. When the time came to remove the boards, the Greensboro History Museum responded to the need of the community to continue the conversations that started on the streets by quickly carving out time and space for an unexpected journey.

Pieces of Now created an arena for discussion and, importantly, a place to be heard and for emotions to be shared. Our History Happening Now documentation and preservation initiative, which had begun in March 2020 as primarily a pandemic story, pivoted in June 2020 to became a Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, Inclusion project focusing on issues of racial reckoning and social justice. As we collected from and talked with protesters, artists, and business owners, we saw clearly that it was important to our African American community that they see these items and responses in the city’s history museum. Pieces of Now was created and installed in just a few months.

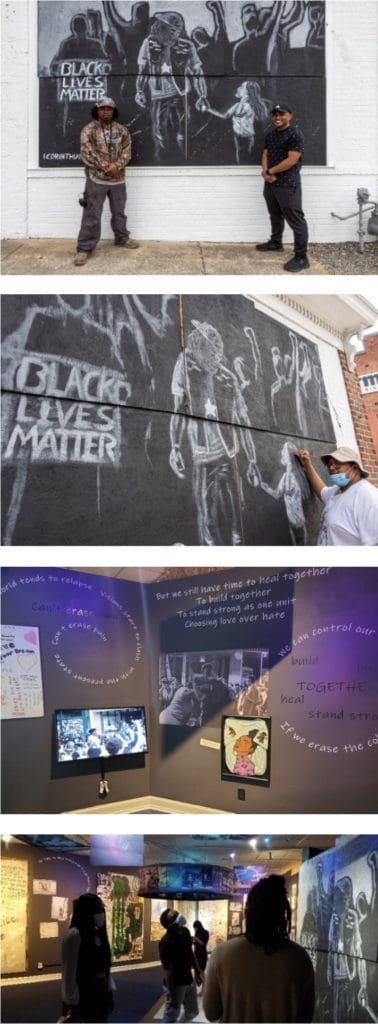

There are three aspects of this project—documentation and preservation, physical and virtual exhibition, and online public/educational programming. These areas provide spaces for conversations about race, equity, and inclusion. The “museum voice,” as seen through written interpretive panels, is muted. Our community does the contextualizing and interpreting through their words and creative expressions. The artists and protestors participated not only by sharing their stories, clothing, paint brushes, and artwork, but also through a series of Zoom webinars, podcasts, and YouTube videos. This process differs from other exhibitions in the museum. It is an experiential space of empathy. It is about Now. It is also unfinished, because we are in the middle of the story. There are very few museum labels; instead, people are telling their own narratives. Long-term goals of the museum include representing many more voices and demonstrating that history is an ongoing, contentious, and often messy process. The impact of the Pieces project in our community was immediate and visible through media interviews, participant networks, social media posts, and the response of city government. We are making meaning together.

These varied creative folk art forms, beyond personal expression, are felt as a shared expression in conversation with each other. The space includes murals by both professional and student artists, graffiti art, Instagram videos, rap, music, protest signs, photography, over 20 video screens featuring interviews, and poetry on the floor and circling through the walls. It is a space meant for emotional sharing, not the presentation of information. Visitors can feel the impact of the public expression of outrage, grief, fear, and unity through creative arts.

In speaking to community members and partners, we learned that it mattered very much to them to know who created the work—whether they were reacting to events or speaking from personal experience with lived pain and hurt. The artworks needed to be understood in the context of the artist; the messages received are highly dependent on who is sending it. When it became known that a curator from the Smithsonian Institution had collected a mural of George Floyd painted by a white artist, members of Greensboro’s African American arts community were outraged. So, it was especially important to identify the backgrounds of the artists. There are no museum text panels with biographical information, rather there are videos with creators speaking about their lives in the moment. While there is plenty to unpack in the work itself, the artist cannot be separated from the work in this exhibition.

In speaking to community members and partners, we learned that it mattered very much to them to know who created the work—whether they were reacting to events or speaking from personal experience with lived pain and hurt. The artworks needed to be understood in the context of the artist; the messages received are highly dependent on who is sending it. When it became known that a curator from the Smithsonian Institution had collected a mural of George Floyd painted by a white artist, members of Greensboro’s African American arts community were outraged. So, it was especially important to identify the backgrounds of the artists. There are no museum text panels with biographical information, rather there are videos with creators speaking about their lives in the moment. While there is plenty to unpack in the work itself, the artist cannot be separated from the work in this exhibition.

While recording protestors’ and artists’ stories, they kept thanking us for inviting them in and listening. Our staff considered community members as co-curators and collaborators, as well as audience. This project requires participation of the community to meet its goals of documenting history as it is happening. We specifically wanted to be sure we had a focused African American presence, in addition to other community members. We also want the exhibition to reflect the diversity of the communities who protested, as reflected in the signage we gathered after the protests. This included Latinx, Asian American, and the LGBTQIA+ communities.

As we developed the exhibition and the online programs, our Curator of Education Rodney Dawson, who is African American, talked with the K-12 teachers who were part of the protest and other teachers in our school district to assess how we could provide content and help develop syllabi for school-aged children in the coming months. Many of the videos and podcasts are being filmed with that purpose in mind. Rodney also has a background in radio and media and conducted many interviews as part of his educational outreach for Pieces. For him, his role in helping others control their own narratives has been vital, as have been the intergenerational connections he witnesses, connections to the history of Greensboro and the nation and connections among people. He explains, “The exhibition offers paths to empathy, not a historical timeline.”

In part because of the pandemic, our online programming and digital content offerings have increased and audiences have geographically expanded. Engagement on social media, particularly creation of Instagram videos, is part of the community conversation. Impact in our wider museum community can be gauged by the national interest in the project. Schools are using the virtual tour of the exhibition for virtual field trips, and the Enrichment Fund of the Guilford County School District has funded all 22 county middle schools to participate. The unforeseen impact on our city’s workplace, after the City Manager encouraged departmental leadership to bring their staff to see the exhibition, has influenced city workplaces. The conversations among staff and leadership, which extended to the City Council, indicated that we had created a place of/for facilitated engagement. Community members continue to participate by coming forward to suggest more stories and materials that should be included.

One favorite example of how art connects people, which has been a touchstone for young students, is the mural by Marshal Lakes based on a photograph by Kevin Greene, a gifted African American photographer and local high school band teacher. It portrays the African American protestor Pastor Michael Harris holding the hand of Emory Llewellyn, a four-year-old white girl wearing a unicorn T-shirt, as they march in protest of George Floyd’s murder. On the wall in addition to the mural, Marching Together, is a photograph of the artist, the photographer, and the white business owner, Tinker Clayton, the artist’s friend through church (who manufactured the Covid-19 mask that city employees wore). We also collected Marshall Lakes’ brushes and paint cans; Pastor Harris and young Emory have donated what they were wearing as they marched. The story of the inspiration and creation of Marching Together was captured in a Zoom session with Marshall, Michael, Kevin, and Emory, which Rodney Dawson led.

Another story connecting with students is that of college student Chimeri Anazia, whose work and interview are in the exhibition. Her submission stated, “I am really glad to create something that people really connected with…. Something so beautiful came out of so much destruction, frustration, and a period of divide. Art can bring people together.” Children are particularly taken with the large red hands Anazia depicted and try to match them to their own hands. An important part of her story is how Chimeri, who had never done anything like this before, felt the need to express herself visually and was helped by experienced artists.

Another story connecting with students is that of college student Chimeri Anazia, whose work and interview are in the exhibition. Her submission stated, “I am really glad to create something that people really connected with…. Something so beautiful came out of so much destruction, frustration, and a period of divide. Art can bring people together.” Children are particularly taken with the large red hands Anazia depicted and try to match them to their own hands. An important part of her story is how Chimeri, who had never done anything like this before, felt the need to express herself visually and was helped by experienced artists.

As we began to meet the protest leaders, we learned that many were artists. Pastor Harris helped us contact Virginia Holmes, the young African American artist who planned and led some of the protests. Virginia volunteered to donate her artwork to the museum. This work differs from most of the murals. There are no words or images, yet it is very powerful. It is now installed in our gallery, not only as an important work of art, but also as a connection to her story.

Virginia and I, a white woman from New York, have had many conversations about her perceptions of this museum. She grew up in Warnersville, the first planned African America community in this area. This community thrived for decades, until urban renewal projects of the 60s forever changed it. We had done a collaborative community exhibition on Warnersville six years ago, which gave us credibility with her. She said we were changing perceptions that we are the “white folks’ museum.” To be invited to tell her story of protest, represent her art, and seek her help to create the exhibition title graphic, means a lot to her. Virginia told me that background has taught her about persistence, not to take things personally, and she has studied her community’s history and injustices. I have learned a lot from her, for example, how she feels disconnected from some arts nonprofits that continue to box protest art into zones that are safe for them, not her. Because of Covid-19 restrictions, we were unable to host an opening party for the exhibition, but one year later, working with the Black artist cooperatives Haus of Lacks and the Collective GSO, Virginia took the lead working with our staff to create a public “art-in” community event.

Reflections on Pieces of Now: A History Happening was a celebration with artists, teachers, and activists reflecting on changes in the city over the past year and persistent systemic racial disparities nationwide. Many of the artists were part of the exhibition and actively participated in the day, creating art in our park as they chatted with attendees. Activities like spray chalk, large chalk drawing on our sidewalks, and written expressions of hope tied to our wishing tree were ongoing while musicians and speakers presented. The chalk work and graffiti were reminiscent of one of the most impactful works in the museum’s exhibition, a reproduction of sidewalk graffiti titled “Dear White Folks.”

This was an unsanctioned piece of public art. On the night of June 8, 2020, a 30-foot long poem, “Dear White Folks,” was spray painted on a downtown sidewalk. City Field Ops contacted us to document it before they sandblasted it away (to discourage graffiti). We photographed it and digitally stitched images together to print it on a three-quarter-lifesize runner for the exhibition. It is a powerful verse that ends in BLM. It is tagged, but although we have put many feelers, the artist/author prefers to remain anonymous. Quick literature searches have not come up with an author. One hope is that by including it in the installation, someone will tell us more about its story. It is a poem, that to some reads like a rap, that has been inspiring to students—another way to express themselves. Interestingly it is the out-of-the-norm placement, on the floor literally beneath people’s feet, that is particularly engaging to students. (Yes, you can walk the talk.)

DEAR WHITE

PEOPLE

WE HAVE TO HAVE A

CONVERSATION

ABOUT RACISM IN

OUR NATION

WE HAVE TO GO DEEP

IN OUR HEARTS

AND ROOT OUT WHAT

KEEPS US APART

WE HAVE TO OPEN

OUR EYES

TO THE PAIN, INJUSTICE

AND LIES

WE HAVE TO SUPPORT

AND LISTEN

IN ORDER TO END

THE DIVISION

WE HAVE TO PRACTICE

WHAT WE PREACH

THROUGH OUR ACTIONS

WE MUST TEACH

WE MUST GIVE OUR

MONEY & TIME

TO CAUSE A SHIFT

IN THE PARADIGM

WE HAVE TO STAND

TIRELESSLY IN SOLIDARITY

AND FACE HEAD ON

ANY DISPARITY

WHITE PEOPLE, WE HAVE

AMENDS TO MAKE

FOR ALL OF THE LIVES

WE LET THEM TAKE

WE HAVE TO KEEP OUR

WHITE PRIVILEGE IN CHECK

AND TREAT ALL POC

WITH EQUALITY, LOVE

AND RESPECT

WE HAVE TO BE STRONG

& FEARLESS IN OUR MANNER

AND SHOUT FROM

THE ROOFTOPS,

“BLACK

LIVES

MATTER”

–TGZ

The other unexpected display of a poem that similarly engages visitors, is “I am Hueman,” by Nakeesha Writes. We had the idea of one strong line of words to snake through the space and keep people moving, rather than conventional interpretive panels. When we mentioned this to local musician/videographer Rasheem Pugh, whom we had hired to record an artists’ discussion, he mentioned his nonprofit, Save the Arts Foundation, and a gifted woman he works with. Within a day, Nakeesha had written and recorded a poem that curls around the walls through the rooms.

Because of the pandemic, school and group programs have used our live virtual tour of Pieces with Zoom, Microsoft Meet, and other online resources. We are developing curricula as we gain more experience, but several themes seem to be of great interest. These include issues of identity, protest history, artistic expression, self-expression, symbolism (when was the raised fist first used?), communication, defining primary and secondary sources, and creativity in protest. Students suggest what they might do to express how they feel, which often is in the realm of the exhibition components they have experienced, but other expressions include plays, video games, a new kind of basketball game, and fashion. Students are seeing the power that the creative arts can have in making a difference in their world.

The Greensboro History Museum’s mission, in a nutshell, is to collect and connect. With the Pieces project, through deep listening and responding to voices of people who have not always felt represented or welcome in the formal museum space, we have connected people through the creative arts. The meanings are often very personal, but within a shared political and cultural context of Now. It is a reframing of museum public space into community space of continued conversation. Public art is seen as a medium of activism, placemaking, self-expression, community building, empathy, and translation. Through a discussion of history and artistic intention and purpose, students are inspired to reflect and explore creative expression within community.

Carol Ghiorsi Hart is Director of the Greensboro History Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina. She is originally from New York, where she was Executive Director of the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum & Planetarium. She has an MA, ABD from Indiana University in sociocultural anthropology with a minor in the arts and anthropology and has been an educator, curator, and adjunct professor of anthropology.

Pieces of Now Project won 2021 MUSE awards from American Alliance of Museums, Media & Technology, including Gold for research and innovation and Silver for 2020 response.