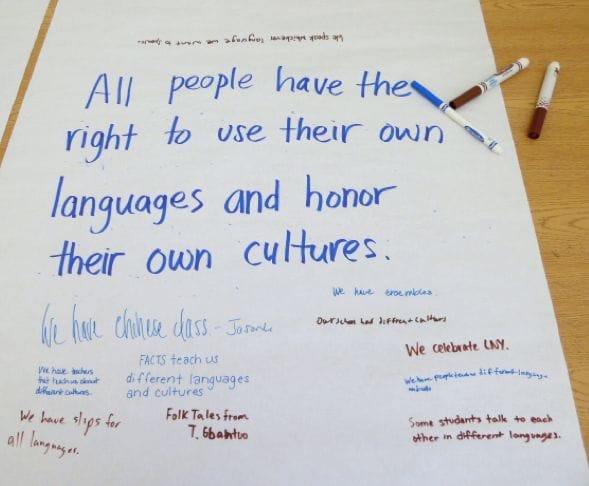

About the photo: 7th graders brainstorm a list of examples of what FACTS does to help them learn this value.

Folk Arts Building Language and Belonging

Schools and educational programs intentionally designed to support the academic, linguistic, cultural, and social-emotional needs of newcomer English Learners (ELs) are rare. Even rarer are schools and programs that interweave folk arts into the educational program for newcomer ELs. Folk Arts–Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) in Philadelphia’s Chinatown strives to do both. FACTS was founded in 2005 by Asian Americans United and the Philadelphia Folklore Project to provide “equity and justice for Asian American students and immigrant and refugee students of all races in the public schools; for public investment and public space in the under- served Chinatown community; and for public schooling that engages children as active participants in working for a just society” (“Who We Are Statement” 2011, 1). This vision continues to drive FACTS’s mission today.

FACTS was founded not to undermine the public school system, but to serve as a model of innovation to inspire change in the education system. By positioning ELs and immigrant and refugee students and families at the center of its school mission and design, the school provides an exemplary education for ELs and creates a model of transformative education for all students. We believe that the educational experience that our society needs today is one that teaches children to find their commonalities across race, ethnicity, language, culture, immigration status, and other differences; raises academic achievement and ability to think critically and creatively; affirms language, traditional arts, and culture; nurtures values of compassion and kindness; instills a commitment to taking responsibility for themselves and their communities; recognizes parents, elders, and community members as a constant presence in the lives of students; and inspires a vision of justice and fairness and the courage to pursue them. Now in our twelfth year, FACTS provides a high-quality, folk arts-infused education to its diverse, student population—13 percent of whom are current ELs, and 83 percent of whom (including current ELs) are PHLOTEs (Primary Home Language Other Than English). In 2016 the U.S. Department of Education named FACTS a National Blue Ribbon School as an Exemplary Achievement Gap Closing School.

English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) Teacher Lucinda’s Perspective on Supporting Newcomer Student Lili

Lili came to 6th grade at FACTS as a newcomer EL in January 2016, just a few days after Winter Break ended. Lili’s mom was smiling from ear to ear while getting a tour from our bilingual Director of School Culture. Lili was shy and reserved and appeared glad to be with her mom. Although she had studied English at her school in China, Lili was reluctant to speak the words she knew. After a few days it became clear that her English lessons in China had laid a very helpful groundwork for her success in the United States. Lili could say and write the Roman alphabet, read and write basic classroom words, and use some basic social language such as, “My name is….” Through my three periods a day with her I came to realize that she had a very firm foundation but lacked confidence—not terribly unusual for a newcomer, but still an obstacle to optimal language learning. I immediately began to consider different ways that I might help build Lili’s confidence and lower her affective filter.

The next Monday it became obvious. One of my 8th-grade students, a newcomer herself four years ago, was heading down to our Chinese Opera Ensemble, and I realized Lili might build her confidence in an ensemble. Ensembles are a huge part of our folk art structure at FACTS and provide students opportunities for deep, long-term learning from experts in their art form. Students can choose to participate and are encouraged to commit to returning each year to deepen their practice. Ensembles can be a place for cultural exploration or affirmation. I have had newcomer students from China and El Salvador participate in ensembles that allowed them to explore the African American traditional art of stepping, and others who moved through the motions of West African dance and drumming. Whether for exploration or affirmation, students who participate in ensembles often walk away with deepened respect for their own culture and the cultures of others. They learn to respect elders and value the hard work and determination required to perfect an art form and work together as a team, an ensemble.

I thought that Chinese Opera Ensemble could allow Lili to use her fluent Mandarin with the instructors, who both used Chinese as the language of instruction for the class. It would also give her a space and time to build relationships with students who shared her culture and language. Finally, I hoped that it would provide her mentorship—both from other students, as well as one of the Chinese Opera Ensemble teachers who had once been a newcomer and now is fluent in English and deeply connected in our wider school community.

On their second Monday, I had an 8th grader escort Lili and another newly enrolled Mandarin-speaking student to observe the Chinese Opera Ensemble class. The next day I asked her, with the help of Google Translate, how she liked it. Lili said it was good and that she would like to be in the class. I could see over the next few weeks that ensemble was helping her to build friendships and giving her an outlet to use Mandarin for learning. It was also giving her an opportunity to engage physically, mentally, and emotionally with a culture-affirming folk group. As time went on, I learned that Lili loves reading about Chinese history. Connecting to Chinese Opera also nurtured her academic interests, affirming the pride she has in the long history of China.

By affirming Lili’s pride in her first language and heritage culture, participation in folk arts education is supporting her English language learning. I have observed that she is happy and has friendships with many girls in her ensemble. She is also positive about her learning and doing well. Her entrance WIDA English proficiency level screener test from January 2016 put her at a Level 1—which is the most beginner level—in all four language domains of listening, speaking, reading, and writing. The subsequent state-mandated WIDA ACCESS for ELLs 2.0 English language proficiency test that Lili took just one month later placed her at a 1.9 overall score. (WIDA tests are scored on a scale from 1.0-6.0, with 1.0 being the most beginner English level and 6.0 being native-like English language proficiency.) Lili continued to make steady progress in all domains throughout the one and a half school years after she arrived.

Having folk arts and artists from the communities and cultural backgrounds of students we serve sends a powerful and important message that students belong, they are valued and celebrated, and they have a right to use their own languages. Further, through practicing an art form students develop friendships and relationships with teachers that give them confidence and support systems as they make the challenging transition to a new culture and new language.

ESOL Teacher Janice’s Perspective on Supporting Newcomer Student Vinny

Vinny came to 2nd grade at FACTS in September of the 2016-17 school year, after arriving from China in August 2016. His dad told us that Vinny moved from the U.S. to China when he was four and attended school there. He had no formal schooling in the U.S. before leaving for China. Vinny was not particularly shy and when asked about school in the U.S., he said he was “not nervous.” His schooling in China had prepared him to write the letters of the Roman alphabet and spell his name. He knew the greeting “Hi” and could do math calculations with numbers. Vinny’s primary language is Mandarin and he was placed in the homeroom of a teacher who speaks Mandarin. I believe that this helped put him at ease because when asked about school he said, “It’s OK, my teacher speaks Mandarin.”

Initially Vinny was very eager to learn and enthusiastic. His WIDA English language proficiency level when tested was a 1.0, the most beginning proficiency level. He picked up new ideas quickly and made strong progress. Then, as with many English language learners, the enormity of learning a new language hit and his enthusiasm waned. Determined to reengage his interest in learning English, I met with my teacher colleagues to discuss how best to do this. At FACTS we have buddy classrooms. Each student gets a buddy as a “big brother or sister.” Remembering the 6th-grade newcomer from last year, I thought perhaps Lili could be a grade-level buddy to Vinny. Teacher Lucinda and I brainstormed opportunities for Vinny and Lili to work with and support one another.

Providing time and opportunities for Lili, the big buddy, to take the role of teacher was valuable for setting a purpose and meaningful interaction. Allowing and encouraging the use of their common first language created an academic space where both could interact and communicate authentically. Embedding their times together within our schoolwide calendar and rituals allowed these newcomers to access the cultural milestones of the school calendar along with their native-speaking peers, but in a way that had meaning for them.

Providing time and opportunities for Lili, the big buddy, to take the role of teacher was valuable for setting a purpose and meaningful interaction. Allowing and encouraging the use of their common first language created an academic space where both could interact and communicate authentically. Embedding their times together within our schoolwide calendar and rituals allowed these newcomers to access the cultural milestones of the school calendar along with their native-speaking peers, but in a way that had meaning for them.

Cross-Grade Class Buddies—Lili and Vinny

At FACTS, we provide many opportunities for students to partner and learn in cross-grade settings. With our newcomers, we have found it valuable for students to have authentic opportunities to learn and teach each other, opportunities that enabled the learners to engage in the co-creation of new knowledge. Given the similarities that Lili and Vinny share as newcomers from China who both speak Mandarin, and Teacher Lucinda and Teacher Janice’s willingness to collaborate, pairing Lili and Vinny as cross-grade buddies seemed a natural fit. Lili and Vinny have had several interactions and joint learning times throughout the year. Most recently they met to share projects they had been working on independently.

Lili, now a 7th grader, had been studying food and culture this year. Through many lessons, she explored why we eat (building community, rituals, and tradition); which foods are common for different children around the world; and comparisons and contrasts of food and ways of eating in her experience in her city in China with how, when, and where we eat in Philadelphia. She also documented special foods she ate with her family during the Chinese New Year. Teacher Lucinda asked Lili to review her notes and create a presentation to teach Vinny what she had learned. Lili worked with great motivation, writing her sentences carefully, translating each idea into Chinese for him, and choosing images appealing to a 2nd-grade eye.

One afternoon, Lili shared her presentation with Vinny. For each part she had prepared a question for Vinny to get him thinking and talking about food. It worked. Vinny had a lot to say and the two would descend into several minutes of conversation after each presentation of the slideshow. We had an additional guest, a Mandarin-speaking elder who volunteers in Vinny’s class and is eager to learn English. She also participated in the conversation and took notes to support her English language learning. After Lili’s presentation, Vinny shared his project with both Lili and the elder. He had been working on a nonfiction, interactive poster about school. The next day Lili prepared vocabulary cards for the keywords from her presentation to help Vinny study for a quiz that she had prepared for him to take a day later.

About a month later, we celebrated Founders’ Day, a FACTS ritual calendar day devoted to celebrating the story of our school’s creation and those who helped create it. Ritual calendar events are very important to our mission at FACTS. Founders’ Day is one such event that tells the story of how FACTS began. The play performed during Founders’ Day each year reenacts the founding in English. Newcomers may understand some things about the story through this theatrical telling, but they cannot grasp everything. To help Lili better understand and participate in the event as a new student the previous year, she had worked with a Mandarin-speaking tutor to interpret the story of Founders’ Day and generate interview questions for a Mandarin-speaking staff member who had been part of the founding of FACTS. We ESOL teachers asked ourselves how we could get Vinny, as well as another 2nd grader, Steve who just arrived at the school and was having some problems adjusting, to be involved in learning this story. We decided to go with our buddy idea. As Lili was hearing the story once again in 2017, she was now positioned to teach about what she had learned. So after the whole school assembly, our two young Mandarin speakers, Vinny and Steve, came upstairs to the middle-school floor of our school to talk more about the Founders’ Day story with Lili.

Lili told Vinny and Steve the Founders’ Day story in Mandarin and answered their questions. The 2nd graders completed a storyboard with a beginning, middle, and end. Vinny used pictorial representations and Steve used pictures and words. We could tell that all three students felt at ease. The conversation was lively and engaging, and the students were building deeper connections with each other and with the FACTS community. Through this cross-grade collaboration, the students learned about their school while honoring their language and heritage. The experience helped to reinforce to all these students that both of their languages (Mandarin and English) were valuable and valued resources for helping them grow and develop as learners.

Folk Arts Practices at FACTS

At FACTS, students’ home lives, languages, cultures, and ways of knowing are honored and respected in the classroom and throughout the school. Folk arts education practices equip teachers with the tools to “recognize the skills and honor the talents that parents, artists, and people who live in the communities can contribute to the whole education of children” (Folk Arts 2011, n.p.). FACTS has intentionally developed a range of schoolwide folk arts practices that are embedded in our school culture; aim to teach the whole child; and foster a sense of belonging among students from diverse racial, cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. FACTS folk arts practices include 1) attending to the culture of the school on both the schoolwide and classroom levels and 2) attending to the inclusion of community knowledge inside the school pedagogical practices. We discuss these in more detail below.

Attending to the Culture of the School

Classroom Culture

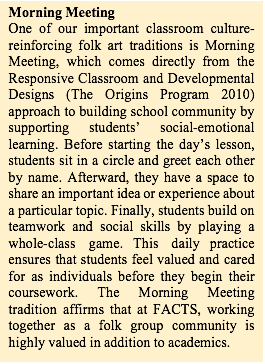

FACTS recognizes that each classroom is an important cultural group (folklorists call this a folk group) in the lives of the students. As teachers, we are the tradition bearers of classroom culture. We seek to establish a caring community where all students feel they belong. Some of our most important work as teachers is to help students learn that being a member of our classroom community means to care for and support one another.

The school has created many traditions that help students realize that being part of a caring community does not stop at their classroom door, all classrooms are equally caring folk groups and together the classrooms form a large community with all students as valued members. We want our students not only to care for their classmates, but also to extend that sense of belonging and caring to all students in the building. The FACTS “buddy” system that paired Lili and Vinny is just one way FACTS integrates practices that foster caring, respect, and responsibility for each other throughout the school. Each year, every class in grades K-3 is paired with a buddy class in grades 4-8. Within each class, a younger student is paired with an older student, who acts as the younger student’s guide, or a “big sister or brother.” Older buddies accompany younger buddies on fieldtrips, sit beside them at school concerts, and make them gifts for special holidays such as Lunar New Year. This buddy system creates relationships and bonds across grade levels and fosters a greater sense of caring between students throughout the school.

In addition to the buddy system, FACTS has developed a unique ritual calendar that further nurtures the schoolwide sense of community, family, and belonging through annual holiday celebrations and traditions. Our ritual calendar consists of special days set aside for the whole school to stop regular routines and participate in special traditions together, such as assembly programs or lessons related to the event being celebrated (Long 2005). The ritual calendar celebrates selected holidays with in-school observances, such as the Lunar New Year, a holiday observed by many in the school’s Chinatown neighborhood community, and by some of our students and their families.

While some holidays are intentionally included and celebrated at FACTS, other holidays are intentionally excluded. For example, FACTS students celebrate Many Points of View Day instead of Columbus Day. The structure of the day and lessons presented that day engage students with the histories and perspectives of Native Americans, who are treated as critical, largely missing piece of the mythologized, dominant narrative of the European explorers (Bigelow, Miner, Peterson 1991). Students are challenged to consider not just the arrival of the Europeans, but also the tragic impact that European colonization had on the Native American peoples.

Inclusion of Community Knowledge in Pedagogical Practices

FACTS pedagogical practices bring students’ personal experiences and community knowledge directly into the classroom. Community knowledge is “content that is situated within a community cultural group or setting” (Deafenbaugh 2015, 76). Some examples include traditional games, songs, or medicinal remedies. When students draw from their own experiences, all students are able to participate in the lesson rather than only a select group who are familiar with a privileged set of academic content. This practice advances academic content because it is possible to use students’ traditions and personal observations as a foundation for critical thinking and student engagement. For example, when students write about their experiences as personal narratives in the English language arts classroom and share them with peers, students advance their “understanding of community knowledge that may be similar or drastically different from their own” (Deafenbaugh 2015, 79).

Community knowledge also comes inside the school when parents and other adults present about traditions or cultural practices. It is possible for students to use academic formats to evaluate or compare and contrast the tradition with their own. By involving community members in the classroom, families are regularly integrated into the school setting and students become more engaged in learning (Deafenbaugh 2015, 80).

FACTS students also take part in community explorations built into the social studies curriculum. For example, every year FACTS 4th graders explore the Chinatown neighborhood where the school is located, visit local businesses, and interview community members. These community field investigations also help students practice the valuable skills of inquiry as they explore details about their own and others’ cultures. In the process, they become active ethnographers rather than passive bystanders.

Finally, FACTS incorporates arts from students’ home cultures through ensembles and residencies. Students in grades 3-8 have the option of participating in one arts ensemble group, such as Chinese Opera (discussed above as part of Lili’s experience at FACTS), Indonesian Dance, Step, and African diaspora drumming per year, and there is limited space in each. The ensemble teachers are professionals who serve as artists-in-residence at FACTS. They collaborate with teachers and students to teach their craft and further integrate folk arts into the school day. Through these ensembles, the school actively engages students with arts and traditions from various home cultures of our school community. Students can choose to learn about and engage in the traditions of their own heritage or those of others. In this way, they may acquire a better understanding of their own heritage or further build their empathy and knowledge for the cultures of others.

In folk arts residencies, artists collaborate with teachers and students to teach their craft and embed their work into the content curriculum. As part of a folk arts residency, students may read or write about a traditional art form or the culture from which it comes; write stories rooted in the art form that the artist-in-residence shares with them; conduct community surveys to find people with local knowledge; record and write oral histories; or use their knowledge of textiles to define mathematical concepts such as symmetry and measurement, for example. By integrating folk arts into the curriculum, students engage with practices that are “owned and known” by our students and their communities (Folk Arts 2011, n.p.). The arts serve as a conduit for passing on valued knowledge. They also add to the multiple modes of learning that take place at the school, especially advantageous for students who struggle with conventional classroom instruction. This generally communicates a sense of belonging and value to students of all learning styles within the classroom. FACTS nurtures the cultural health of its students, teachers, and community and integrates folk arts to “bridge children to elders, school to community, and school community members to each other” (Folk Arts 2011, n.p.).

Conclusion

Folk arts provide the unifying thread across our culturally, racially, and linguistically diverse student body. We emphasize folk groups as the social and cultural contexts in which students, teachers, and families create folk arts, which helps support community building across all aspects of the school day. Newcomer children and families, whether they are immigrants, refugees, or asylees, must negotiate an overwhelming number of factors as they integrate into life in the U.S. These factors may include, but are not limited to, cultural expectations and norms (both spoken and unspoken), U.S. systems and institutions, language barriers, prejudice, discrimination, and potential trauma and feelings of isolation. It is critical that schools are aware of the many challenges that newcomers face and that they provide comprehensive supports for this vulnerable population as they acclimate to their new lives. At FACTS these supports include a multilingual staff, a nationally recognized ESOL program, routine translation of school documents into students’ home languages, multilingual interpretation at school events, and an inclusive, folk arts- rich school culture and instructional program. By recognizing and fostering the folk groups that exist at FACTS, we “move past ethnicity and/or culture as the only feature of [students’] identity, and as the only source of folklife” (Philadelphia Folklore Project 2009, 2) and provide rich, expansive opportunities for students to explore, develop, and confirm their identities. This creates the conditions for all students, including newcomers, to enjoy a sense of belonging, thus enhancing their chances for success.

Lucinda Megill Legendre teaches middle-school ESOL and serves as Middle School Coordinator at FACTS. Janice Prevail teaches Kindergarten to 2nd-grade ESOL at FACTS. Kristin Larsen taught 5th-and 6th-grade ESOL and now serves as FACTS ESOL Coordinator. Amy Brueck taught 3rd- and 4th-grade ESOL at FACTS. She currently teaches English in Indonesia. Linda Deafenbaugh is the FACTS folklife education specialist and coordinates folk arts education programs and research for the Philadelphia Folklore Project.

Works Cited

Bigelow, Bill, et al. 1991. Rethinking Columbus: Teaching About the 500th Anniversary of Columbus’s Arrival in America. 1st ed. Rethinking Schools in collaboration with the Network of Educators on Central America.

Deafenbaugh, Linda. 2015. “Folklife Education: A Warm Welcome Schools Extend to Communities.” Journal of Folklore and Education. 2: 76-83, https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Deafenbaugh.pdf.

“Folk Arts.” 2011. FACTS, http://www.factschool.org/en/folk-arts.

FACTS Governance Committee of the Board. 2011. “Who We Are.” FACTS, http://www.factschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/FACTS-WhoWeAre.pdf.

Long, Lucy M. 2005. “Holidays and Schools: Folklore Theory and Educational Practice, or, ‘Where Do We Put the Christmas Tree?’” CARTS Newsletter, https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/lucy_long.pdf

Philadelphia Folklore Project. 2009. “Resources for Folk Arts Education.” August, accessed May 4, 2017, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B97s8MFuR6HEWVhhNjN0OV9NZms/view.

The Origins Program. 2010. Developmental Designs 1 Resource Book, accessed May 4, 2017, https://originsonline.org.