How Folk Tales Enhance the Cultural Meaning of Yoga

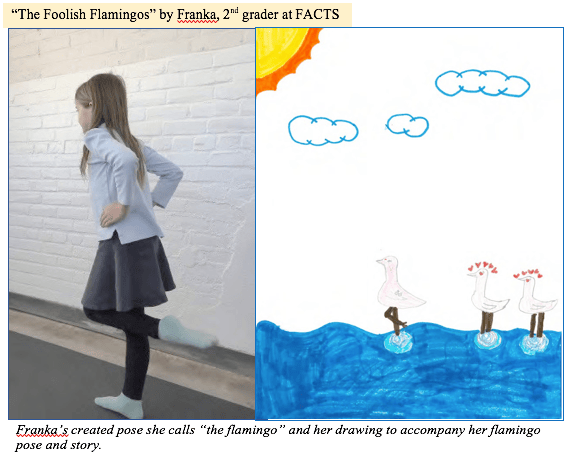

FACTS 2nd-grade student Franka’s created pose

she calls “the flamingo.”

How Yoga Tales Began: The Artist’s Story

by Nisha Arya

As a first-generation American born of Indian immigrants, I have often felt that I do not belong to the community in the Philadelphia suburbs where I live. In the predominantly white suburban school where I am a student, I am viewed as Indian. But on my annual family trips to India, unfamiliar with many Indian customs and traditions, I am an American. Where then do I belong?

My Journey of Learning to Belong

Outwardly, in terms of dress and accessories (jeans, T-shirt, backpack, and smartphone), I look as American as any other teenager in my school. I have hardly ever been discriminated against because of my skin color. Yet I have always known that I am different. I grew up with many Indian traditions and values at home. We eat Indian food and celebrate Indian festivals. I learn Hindustani (Indian classical) music and how to read and write my family’s native language (Hindi). For most of my life, having grown up with these traditions, I have taken them for granted. But as I entered my teen years, I started to resent them as I realized that they made me different from my friends and harder for me to belong and fit in.

In 9th-grade social studies, during the week devoted to India in the Africa-Asia unit, we discussed Indian traditions and cultural practices with which I did not connect, such as the caste system and the fate of widows in medieval India. Later the same year, in an introductory yoga lesson in physical education class, our teacher led us through the Sun Salutation. Although I knew relatively little about yoga at the time, I showed off my knowledge by saying that the Indian name of the pose was surya namaskar. The other students were surprised, some were even shocked to learn that yoga originated in India. One insisted that yoga was too sophisticated to be from a country where widows were burned on the funeral pyre. Hurt and angry, I could not find my voice to speak up. In the days following, I thought: What, if anything, could I do to teach my friends about my culture? Would exploring, learning, and sharing my heritage with my friends assuage my hurt and improve my sense of belonging?

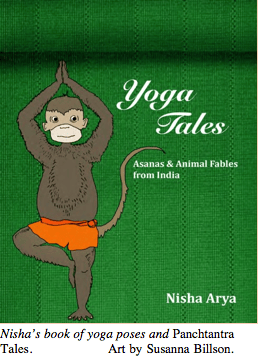

Inspired by a trip to India that led me to study yoga and the ancient Panchtantra Tales, I developed a yoga and folk tales project during high school. These fables are whimsical stories of animals with human qualities of greed, generosity, anger, love, revenge, and hate. Composed in Sanskrit thousands of years ago, the stories are rooted in India’s customs and philosophy and remain immensely popular. As they have been passed down generations and translated into India’s numerous languages and dialects, they continue to provide insights into the dreams, values, and attitudes of people from India’s diverse cultures.

I chose ten animal yoga poses to pair with ten fables for a children’s picture book. For example, the folk tale for the crow pose (Kakasana) features a story in which a pair of crows takes revenge on a snake that ate their newly hatched eggs. The cow pose (Bitilasana) is paired with a story in which three young boys steal a cow from a poor Brahmin. Each is illustrated by a Philadelphia artist familiar with Indian culture and traditions.

Armed with my book, I approached the folklife education specialist, Linda Deafenbaugh, at the Folk Arts–Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) in Philadelphia. A teacher at FACTS, Daisy Ling, expressed interest in incorporating the book into her 2nd-grade physical education curriculum and invited me to share my cultural knowledge with her students. I served as a visiting artist during an extensive unit on yoga and folk tales. During my visit, I watched with a sense of wonder as seven- and eight-year olds demonstrated their learning from the first two lessons with the classroom teacher by rolling out their mats, taking off their shoes, and sitting still in the lotus position. The teacher invited me to participate. I taught more advanced poses, read a story aloud, and answered numerous questions that demonstrated students’ curiosity and interest in a new cultural tradition: How old were you when you learned yoga? Where is India? How many yoga poses do you know?

As I shared my cultural knowledge, I realized that I was helping students, and myself, gain a multidimensional perspective. By enacting yoga and reading folk tales, students not only performed yoga, they experienced it. Folklore gave yoga cultural context and meaning so that it evolved from a physical exercise into a cultural experience. Sharing my narrative also led me to a more complex understanding of myself. In finding my voice and sharing my cultural awareness, I discovered more of my cultural identity.

I recognized that my heritage was different from that of everyone around me, but now I was unafraid and celebrated it. I felt empowered by the valuing of my work and others’ validation of my cultural knowledge. When a 2nd grader in the first row eagerly told me how she had read the stories over and over again and practiced yoga poses at home with her mother, I felt part of a diverse welcoming community. In sharing my cultural knowledge, I had achieved a sense of belonging that had eluded me.

The Teacher’s Story

by Daisy Ling

Folk arts education conversations are a common feature in the Folk Arts–Cultural Treasures Charter School (FACTS) hallways. We are continually seeking ways to integrate community knowledge from Philadelphia’s many cultural communities as learning resources across the curriculum (Deafenbaugh 2015). One afternoon, Nisha Arya was visiting FACTS and presenting the idea of integrating her yoga tales book into our school curriculum to our folklife education specialist Linda Deafenbaugh, when I joined the conversation. Linda was mulling over integrating this folk art by breaking the book’s content apart so that movement might be in physical education as well as literacy in the main classroom, but I thought integrating both movement and stories at the same time in a physical education classroom was the better approach.

I had wanted to do yoga with my students but had not thought to do it with 2nd graders until Nisha brought in her great book. Conducting folk arts education lessons with 2nd graders has limitations based upon their developmental ages. Seven- and eight-year olds are fairly concrete learners, so much of understanding a folk art lies in the intangible complexities of symbols, meanings, and worldviews. Stories, however, are tangible and present an ideal approach to accessing deep culture for this age group. Nisha’s book matched the stories with the movements, opening up the possibility for these youngsters to grasp the culturally grounded movement practice of yoga and learn the aesthetic values that guide its practice of flexibility, strength, balance, focus, breathing, and calmness.

Yoga would be the third folk art form of movement traditions that these students would be learning this school year. These same 2nd graders had worked with folk artist Losang Samten learning Tibetan meditation and were taught a story through the beautiful sand mandala he made. They had also recently finished a West African dance residency with another folk artist, Jeannine Osayande, in which they focused on dance movements and accompanying songs as telling the stories. To continue their learning of what folk arts are and the deeper meanings that folk arts contain, these same students would now explore distinctly different Indian cultural values and worldview through the yoga stories and movements. Each movement tradition is guided by a different set of aesthetic values that establish the boundaries for how to move bodies and use space. The opportunity for these students to compare and contrast three movement folk art forms was exciting.

Yoga would be brand-new to our 56 2nd graders. We determined that the unit’s main goal would be for all students to develop a better understanding of what yoga is, make a connection between the animal- named poses and the animal fables that they would listen to and read, and increase their self-awareness by working on their body through the different yoga poses. Our overarching folk arts education goal was for these very young students to deepen their understanding of how folk arts are part of everyone’s lives.

Folk arts integration means accomplishing folk arts education goals and content area goals at the same time. I have wanted to work more on folk arts integration in a physical education setting but have found it somewhat difficult. One of the easiest ways to integrate is to partner with a folk artist in residence, but FACTS could not afford to hire a folk artist for a residency in my class this year. Therefore, I have had to find other ways to integrate folk arts into my curriculum. Nisha was presenting a wonderful folk arts integration opportunity for me. Her availability was limited, so she could only be a visiting artist. Nonetheless, I was excited because students needed to interact with her to make the connection that this art form is her cultural tradition.

Folk arts integration means accomplishing folk arts education goals and content area goals at the same time. I have wanted to work more on folk arts integration in a physical education setting but have found it somewhat difficult. One of the easiest ways to integrate is to partner with a folk artist in residence, but FACTS could not afford to hire a folk artist for a residency in my class this year. Therefore, I have had to find other ways to integrate folk arts into my curriculum. Nisha was presenting a wonderful folk arts integration opportunity for me. Her availability was limited, so she could only be a visiting artist. Nonetheless, I was excited because students needed to interact with her to make the connection that this art form is her cultural tradition.

Yoga is often practiced in schools and gyms throughout the country, but I wanted to go beyond and teach yoga as a folk art in my physical education class. To maximize learning, students needed to interact with a folk artist and I needed a partnering artist. Nisha was only available to co-teach one lesson with each of my two classes. I had to concentrate student learning time with her, and I had to increase my understanding of the breadth of yoga to support student learning productively. We planned a seven-lesson unit. I would teach two lessons prior to Nisha coming to FACTS to co- teach a lesson, and then I would conduct four lessons after her visit. I could direct students to hold certain animal poses while I read the corresponding story to them from Nisha’s book. This method allowed students to focus on the story and the meaning behind the story as they were working on their flexibility, balance, and strength. It was a good way to train young minds away from thinking about any muscle tension they might be feeling and toward a focus on something interesting and positive.

When Nisha visited, she read two stories, performed various movement poses, and told her story. My students worked on their interviewing skills to ask her questions they had for her about her art, her life, and her culture. I felt comfortable teaching most yoga poses, but for some of the more difficult poses I needed Nisha’s expertise. Nisha’s visit allowed my students to work on those harder poses with her expert guidance and allowed me to aid those students who needed help or modifications so they could progress. With Nisha’s photographs modeling a yoga pose on every page of her book, students could maintain their connection with her even when she was not in class.

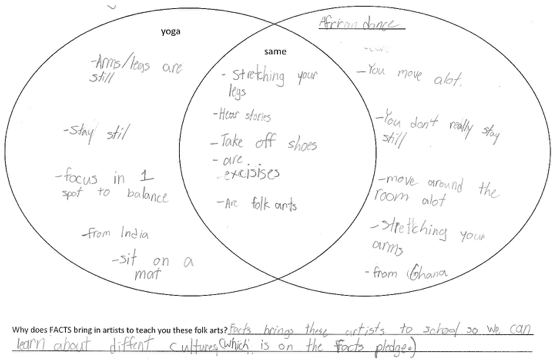

Although students continually demonstrated their learning and I had been monitoring their progress via observations of each child throughout the unit, we added a final synthesizing activity at the end of the unit to assess learning about folk arts more broadly. We conducted a review in which students discussed what they had learned and remembered from prior units with Tibetan meditation and West African dance. Students then completed a final Venn diagram comparing yoga with their choice of one of the other folk arts forms they studied. The final Venn diagram assessment shows the degree the students were understanding the similarities and differences between the traditions.

The unit plan and individual lesson plans may be found on the FACTS website and Nisha’s book may be found here.

Observations and Reflections about the Unit

Integrating any other subject into physical education is challenging because movement is the top priority, especially in a nation beset by childhood obesity. It is important that we tap the knowledge traditions of the many cultural communities outside our schools to increase movement as part of students’ lives. Supporting students’ academic advancement is also extremely important and more effective with integrated learning activities that bring the whole child into the classroom. This yoga unit was designed as an integrated unit–not just for physical education and folk arts but also for language arts. Integrating language arts and body movement fully presented many challenges, even with Nisha’s book. I had many students who were interested in the yoga poses and challenging themselves to perfect them, but many were more intrigued by the book. I learned that passing out the books to students could be a problem, especially for those who wanted to read more than they wanted to follow along and perform the poses. I found that students were very quiet while I read the tales as they focused on doing the poses. We had great conversations and discussions after reading each tale. Students enjoyed the stories so much, they wanted me to read them over and over.

Students were able to connect the ideas behind the Indian traditional Panchtantra Tales. Some were able to connect that when they were doing the pose, they were acting out that animal’s part in the story. They were being the animal that chose to do the right thing versus the animal that hurt other animals. Students connected most with the “The Foolish Frog.” In this story, the frog wanted his siblings to be eaten by a snake because the frog was being teased and bullied. Students understood this gruesome tale and its cautionary moral as a story about bullying. In our discussions, students stated that the story meant that they should “never bully others because it might end up coming back to hurt them in the end.” Students were able to make a bigger connection with that story then I thought seven- and eight year-olds would make. There was similar high-level thinking in what they expressed while discussing the other tales. I noticed that discussions became deeper each week. I entertained the thought of having students read the tales to classmates because of how much they were getting out of each story, but I could not give too much class time to non- movement activities; students have precious few minutes in each school day to move as it is.

Another source of insight was a short mid-unit reflective writing activity students did after Nisha’s visit. Students expressed how they felt while doing yoga, what poses were their favorite, which pose was difficult, and how breathing while doing yoga helps them. I appreciated their reflections. Many students had similar answers for what pose was their favorite and which they thought was most difficult. We also asked students to state where they heard stories besides reading them in books. Their answers of teachers, parents, siblings, in movies, and at libraries gave me an idea from whom and where these students have opportunities to hear folk tales. I am glad students were able to make a connection to stories being a feature of their lives—that they do not just hear stories in their books at school. This is a small step toward their realizing that folk arts are a regular feature of life.

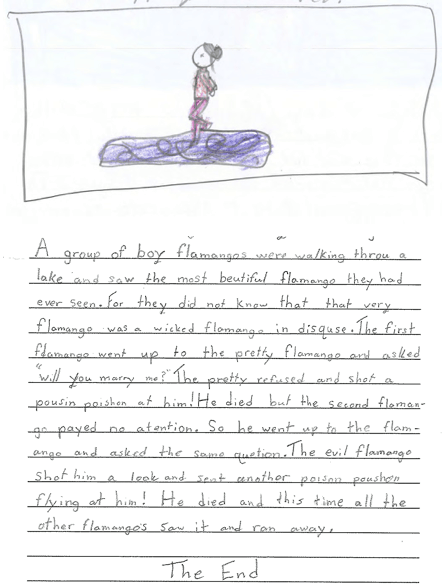

Providing students the opportunity to create a story and yoga pose in the final lessons really helped them connect more deeply to Nisha’s book. Students who create within a folk art tradition demonstrate their depth of knowledge of the boundaries and characteristics of that tradition that they have internalized so far. I was amazed by the creation of poses that went along with their stories. Students created more difficult poses and some showed major flexibility. Students wrote stories with characters related to their yoga pose just like they experienced in the tales that they had been reading. I was fascinated with their illustrations. Some students drew their pose along with their illustration, although I had not asked them to draw their pose. They told me they wanted their pose to be shown just like in Nisha’s book. A photograph of each student’s pose was taken for documentation. Homeroom teachers provided students extra time to rewrite their story on lined paper and fully color their illustrations. This level of support by others in the school made it possible to pull the student work into a book that will be available for future 2nd graders. I fully intend to teach this unit for many years, and the classroom yoga tale books are sure to model and encourage future students to engage more deeply in learning yoga. Next year I plan to work more closely with the classroom teachers to align this unit with the 2nd- grade language arts units. We hope to have the students spend more time working on their own stories in a classroom setting that is better equipped for the task of writing.

“The Foolish Flamingos” is Franka’s story to accompany her flamingo pose, also illustrated through her pose drawing.

From a physical education skills vantage point, at the end of this unit I observed that many students had improved in flexibility and balance. Many students were not particularly focused at first, but as lessons went on, this changed. Many students increased their focus and engagement in both the stories and the poses. I was shocked that many students were able to do the more complex poses, as I anticipated young students would have more trouble balancing. So many students surprised me with their ability to perform crow, and other advanced poses, without modifications. Of course, I modified advanced poses for other students. By the end of this unit, I was able simply to name the animal and students showed me the pose without my demonstration.

Students really enjoyed the final extension lesson introducing partner poses. This lesson provided an opportunity to work cooperatively with another student in the class. Interestingly, they had been looking forward to this lesson since the beginning of the unit. Students liked the ideas in the folk tales about not excluding others. When I assigned students partners, some were paired with students with whom they do not normally work or play. It was great to see them work together, supporting and challenging each other. I recognize that this lesson went outside Nisha’s tradition and the aesthetics of yoga as she practiced it, but it reinforced the Indian cultural values she taught. I appreciated finding a good video resource to show the yoga partner pose and movements by expert pairs. With the modeling on the screen, I could walk around and monitor for proper form as the pairs attempted each pose. Some were able to get into each pose right away and some were challenged, but they all tried their best with each partner pose that I introduced. I did not see any groups give up.

The final step was completing the synthesizing Venn diagram. We discussed all three folk art forms that they learned over this school year. Students listed similarities and differences among all three. They could recognize that each tells a story whether it is encoded in a mandala, a dance, or a pose. Students easily recalled the cultural group of each movement form. They talked about each art form’s aesthetics and described the differences in body position that were valued, if it contained fast or slow movements, where they would perform this art form, if in their doing the movement it was loud or quiet in the room. In the next class, students could choose the folk art form that they wanted to compare and contrast with yoga. They could pull from the previous week’s review to form their own Venn diagram with the similarities and differences that they thought were most important. Some students added other similarities and differences that we had not discussed. They had lots to say about what they were learning about folk arts.

Having a folk artist collaborate with me is always such a valuable opportunity. Working with Nisha made me more comfortable teaching this unit. Without the Yoga Tales book I am not sure I would have done a folk art unit on yoga. Perhaps I might have done a few yoga lessons with older grade levels, but I never would have thought about teaching yoga to some of my youngest students. These students showed me how much concrete and abstract learning they are capable of accomplishing. This is what can come from hallway conversations in our school! Actually, I am glad I took on this challenge of creating this folk arts integration unit. I conquered a challenge that I might not have accepted without Nisha approaching my school with her wonderful book that she has created and without Linda Deafenbaugh’s guidance and support.

Nisha Arya is a senior at Lower Merion High School near Philadelphia. She is president of the Intercultural Youth Council, a student-run organization that brings together young people of different faiths and cultures to create and share poetry and work with children at the Philadelphia Children’s Festival. She plans to study anthropology and neuroscience with a view to understanding how culture impacts and can be incorporated into science education.

Daisy Ling has been teaching at FACTS since 2015, where she is the Kindergarten-8th-grade health and physical education teacher. She has a Bachelor of Science in Health and Physical Education and Master of Education in School Health Programs. Since she began at FACTS, she has integrated folk arts education in her teaching practices. She is looking forward to creating even more learning opportunities for her students to explore folk knowledge about health.

Works Cited

Deafenbaugh, Linda. 2015. “Folklife Education: A Warm Welcome Schools Extend to Communities.” Journal of Folklore and Education. 2:76-83, https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Deafenbaugh.pdf