This article touches on cultural, linguistic, and technical issues that arise in video recording stories of Deaf individuals who use American Sign Language (ASL). Whether you are Deaf or hearing, documenting ASL interviews presents complex film making challenges. Unlike audio or spoken language filmed interviews, recording a conversation in ASL requires full documentation of a signed message along with careful editing decisions to determine what the viewer sees.

While interviews with Deaf people are often conducted in ASL, the film may be shared with audiences who do not know the language. The end product must be bilingual—meaning two languages, in this case ASL and English—and bimodal—using two modes of expression, visual and auditory or signed and spoken. Captions add text to the presentation. With planning and dedication to access, filmed interviews can effectively reach Deaf and hearing audiences.

For Deaf interviewers fluent in ASL this article may seem to state the obvious; we hope some of the technical information is useful. For hearing interviewers, consider who is on your interview team. Collaboration with Deaf people–cinematographers, editors, Certified Deaf Interpreters (CDIs), production assistants, cultural consultants, and historians will enhance your ability to engage with the interviewee and produce a meaningful interview. With cross-cultural projects, community collaboration is essential to accurate representation. Try to ensure that the interviewee is not the only Deaf person in the room.

What’s in a Name?

Narrative history–or what is often called “oral history”–interviews can raise issues pertinent to the Deaf community or the local geographic area. Conversations can be biographical or focus on a sense of place, patterns of behavior, traditions, or beliefs. In the U.S. Deaf community, the term “narrative” (signed “story”) is sometimes preferred over “oral” because of an enduring history of “oral” education that has powerful, often painful, connotations for many Deaf adults. Historically “oral” education meant learning without signing, the visual/tactile means of communication used by the Deaf community. To be caught signing in an oral-only school usually resulted in punishment. Using “narrative” or “story” history to describe the interview sidesteps an unintended reference to oralism that may be brought to mind with the word “oral” and can help build rapport with the interviewee. Before reaching out to a Deaf individual to discuss an interview, consider how phrases such as “oral history” or “give voice to” might be taken.

What Are You Trying to Do?

Consider the purpose of your interview because it will guide how you document the discussion. Are you trying to enlighten history via documenting an event or locality and interviews with Deaf people are part of a more expansive effort that includes interviews with hearing people? Are you trying to understand a social “ism” (racism, sexism) via a Deaf lens? Are you trying to get at what is specifically Deaf? Deaf stories often reveal what it means to be part of an embedded community. They might explain how technology impacts life, or how medical science has changed the Deaf physical or cultural experience. The intersectional nature of Deaf lives is often expressed in stories about religion, race, gender and gender identity, or immigration circumstances. Childhood memories reveal how communication happened within a family that did–or did not–sign and how that affected the way a child felt at home. Members of the Deaf community, like members of many communities, use stories to amuse, instruct, reinforce shared values, show solidarity, and challenge stereotypes. Unless you have unlimited time and filmmaking resources, define the purpose of the interview and narrow the scope.

Pre-Interview Research

Documentaries are often peppered with expert interviews, usually with people who have written extensively on a subject and bring a well-known perspective. Their answers can be polished and, for the filmmaker, predictable. This is unlikely to be the case with most members of the Deaf community. Rarely is there primary source writing from or about the individual. Without sources, it’s difficult to know if the individual will tell a story that is relevant to the research at hand. Fortunately, learning a Deaf person’s basic story is often quite easy by reaching out to community members. The Deaf community is small and interconnected through schools, clubs, and organizations. One person leads to the next, and before long a list of proposed interviews grows to multiple pages.

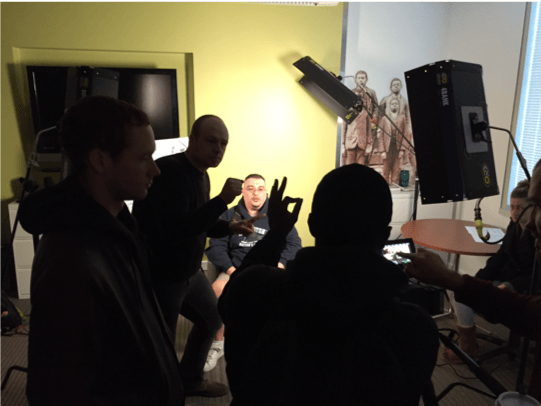

Interviewee John Zakutney shares a story about serving as a test subject for NASA as interviewer Maggie Kopp listens. Note the size of the image on the small screen and the angle of the camera. The interviewee takes up about two-thirds of the screen space and is not centered.

Pre-interview discussions can be done in person or via videophone. Relay services can interpret the call if you do not know ASL, but it may be more effective to work with a consistent interpreter or a Deaf team member for direct communication. Video conferencing is another way to have a pre-interview discussion when you describe what you are doing and why, how long it will take, and who will be in the room. Discuss topics but not specific questions if you can avoid it. Gather years they attended a school or were a member of an organization or other data that will help you formulate interview questions but don’t venture into their stories. Ask if they have any photos or footage they wish to share, and determine if the questions you plan to ask are germane. An excellent resource for preparing to interview is the Oral History Association’s Principles and Best Practices webpage. Although these guidelines primarily address audio recordings, the concepts of ethical behavior and intellectual honesty are the same, as is the responsibility to ensure preservation of the interview.

A crucial pre-interview component is determining language preference and comfort with the interviewer. Deaf people use a wide range of signing styles. Some sign ASL with all the grammatical features of the language. Others use sign in English sentence structure. Some use their voice. It is important to ensure that the interviewee is comfortable with the interviewer. Can the interviewer match the language used by the interviewee? If not, the danger is that the interviewee may “code switch” to fit the interviewer or the interpreter. Ideally, the interviewer or interpreter will know local signs as well as the history and geography of the area.

Mapping “Deaf spaces” can be part of the research process to prepare for interviews. This image shows Deaf organizations, schools, and meeting places in midtown Manhattan.

Interviewees may be more at ease with someone who is also Deaf, or the same gender or race, but this is not always the case. Familiarity comes with its own issues. Interviewers who are part of the Deaf community will be asked their story. Who are your parents? What is your connection to the school or organization? Be sure to provide time for the interviewee to get to know the background of people in the room, including the interpreters. Community membership raises questions of privacy. It may also raise expectations that you will help the interviewee, their family, or the local community in a specific way, or that this new connection will be open-ended. It is important to be clear about what you can and cannot do, who this interview may help, and how.

During the pre-interview, describe any “Informed Consent” or “Video Release” documents that will require the interviewee’s signature. Provide any documents used by your organization in written and, if possible, ASL formats prior to the interview. Consent documents generally cover what the individual is asked to do, how long it will take, whether they will be paid, language used, risks and benefits, confidentiality, voluntary participation, results of the interview, and how to contact the researcher. Video release forms cover confidentiality and storage of the filmed interview, as well as access and dissemination limits. Most institutions have standard release forms.

Developing Questions

Interviewing Deaf people in ASL in many ways is like interviewing hearing people. Open-ended questions that start with “why, how, where, tell me about” lead to stories. But ASL has a cinematic quality so occasionally asking “show me” will produce an evocative story. For example, when asking to be shown how a linotype print machine works, the detail and visual representation in the answer can feel real and take you to the print room. Hands lightly tap keys; metal type slides into slots for placement; hot lead is pressed, cooled, and dropped for a composer to place and quickly proofread reversed lines of type while discerning minute adjustments needed in a line; the page is “locked up” and sent for imprint and the whole process starts over when the lead is fed to be melted and reused. In ASL you can see this process, not imagine it from a description. Think in advance about what questions you can start with “show me.”

Intern Brianna DiGiovanni is creating informed consent and video release documents in ASL for the Drs. John S. & Betty J. Schuchman Deaf Documentary Center.

In ASL it may be more effective to establish the topic and then ask for comment about it. While you want open-ended questions that do not lead the interviewee, it is important to be clear, even blunt, in asking. Usually in narrative history, interviewers try not to give selections, but sometimes options clarify. For instance, “how did you communicate” might be too broad. If you are trying to determine if someone signed or spoke you may want to ask how they communicated with teachers–and then with students. You might ask about the school’s signing policy. If that does not work you might ask if students signed or spoke or used fingerspelling. You might break that question up for use in class, out of class, or on the sly.

Listening in ASL comes with a constant exchange that confirms a message is received. The person “talking” looks at the one “listening,” who is usually nodding–not in agreement but in understanding. As with any interview, listen intently. That means watching, and if you are listening to an interpreter, keep your eyes on the signer. Focus on the answer and avoid thinking about the next question. Wait longer than is typical in an everyday conversation before moving on. A follow up might be a facial expression–eyebrows up or a head tilt that asks for clarification or expansion on a topic. Sometimes the statement after a long pause is the most revealing. Don’t rush.

Questions will vary based on the individual and discoveries made during research. If the interview is biographical there are some common experiences that could be discussed. Answers to questions about childhood memories, language used at home, school experiences, organizational membership, work life, barriers to information and employment opportunities, and technology use will likely reveal common Deaf community threads.

There are questions that would only be asked of members of the Deaf signing community. How did you get your sign name? What do you think of it? What are the city or regional signs that outsiders do not generally know? What is a Deaf joke? Can you can share one? What does the “Deaf grapevine” mean to you? How did you learn to sign? Were there times when you were forbidden to sign? What happened if you did? What kinds of technology do you use in your home today? Can you tell me about getting that technology? What did it change for you? Can you describe any efforts to medically “cure” or religiously “heal” you? Show me what that was like. As with any interview, ask if there is anything else they want to share.

The majority of Deaf children are born to hearing parents and are the only Deaf person in their family. Being Deaf will often affect communication, language use, and identity. Deaf children may learn language and Deaf identity outside their family. Questions about family often conjure up deeply felt responses if the family home was not a place where communication was comfortable and clear. For more on cultural identity read Inside Deaf Culture, by Carol Padden and Tom Humphries (2005), or see the online Deaf Studies Digital Journal (Gallaudet University Department of ASL and Deaf Studies 2009). If the Deaf community is unfamiliar to you, be self-aware of your assumptions and bias about what it means to be Deaf, and, conversely, what it means to be hearing.

Confidentiality

In any small community there may be dangers in being interviewed. The Deaf community is interconnected not just within close geographic areas, but nationally. It may be impossible to give any detail without someone figuring out who you are talking about during the interview. If the interviewer knows the family or friends of the interviewee there may be another layer of concern for privacy. Finally, if the interview is being conducted in a public space, a Deaf club or a school, others may see what is being signed, even at a distance. There is no privacy in public spaces. All these factors will affect how much an individual chooses to share, and it is critical that they understand exactly how their interview will be used, stored, shared, or protected.

Clarity of Visual Image

On screen, what’s behind the interviewee can distract from the signed message. It’s not necessary to have a blank wall or green screen. Context helps the viewer understand who this person is and what their life is like. But backgrounds for filming need to be plain or blurred enough to allow viewers to focus on the signed message. Take time to look at what’s going on in the space behind the interviewee. If a clock, lamp, or hanging mobile catches your eye, ask if you can move it. Try to pull the individual away from any wall to add depth to the visual image. Avoid harsh light or shadows. For seated interviewees, use a chair without arms that does not rock, swivel, or squeak.

Clothing should be a solid color that contrasts with the skin tone of the individual on camera. Explain this to interviewees and ask that they wear solid colors. Nail polish can be distracting and pointing this out may compel some to remove it for an interview. Jewelry is best kept simple; necklaces can be distracting. Minimize anything that diverts attention from the content of the interview.

Test camera settings to ensure you are capturing the complete message. Is the fingerspelling clear? Rapid movement of the hands can look blurry if the lighting and camera settings are out of sync. While the focus is on the face, without clear fingerspelling you will not have an understandable interview. Do the hands extend past the frame? If so, widen the shot. Check settings while preparing for the interview, on site and with the lighting you plan to use.

Light the Dominant Hand

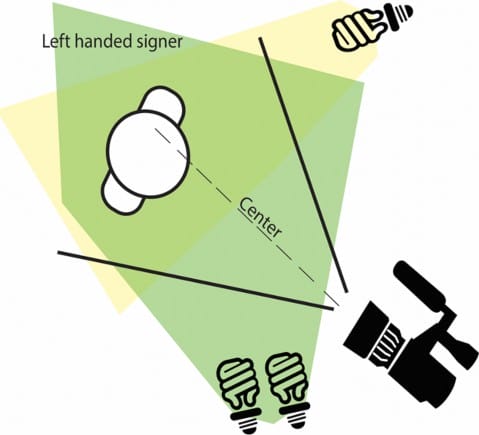

In ASL the dominant hand is the one used to fingerspell. This hand also does more of the movement for many signs. Lighting the dominant hand more prevents shadows from impeding readability. There is more than one way to do this, but use the image below as a guide. Notice that the person is not sitting in the middle of the camera shot, but slightly off to the side. Shoulders are at an angle to the camera. More light is shining onto the hand that fingerspells words. Slightly more space is on the side of the dominant hand. This format gives the interviewee room for large signs that extend past the body. It also creates a more interesting visual image than sitting precisely in the middle of the screen with shoulders square to the camera.

This set-up diagram shows placement of the camera, interviewee, and lighting for a one-camera interview. Illustration by Zilvinas Paludnevicius.

One Camera? Two? Three?

Depending on your crew, budget, and proposed use of the film, there are several ways to set up cameras. First determine if you want or need the interviewer and/or an interpreter on camera. Two people on in one shot can make viewing more difficult, especially on a small phone screen. Is seeing the interaction between two people important? Can you show the question in text form, or do you need it at all? Can you use two cameras and cutaway in the editing process? Do you need that extra camera to capture extreme close-ups that more clearly show emotion? How the footage will be used guides decisions on camera set up.

The simplest format is using one camera solely on the interviewee, or one camera with both interviewee and interviewer sitting together. A good example can be seen in the Council de Manos Know Your Story collection. In the shot, Carlos Aponte-Salcedo, Jr., is interviewing his father as they sit on the same couch about growing up in Puerto Rico and moving to New York City. This format requires minimal editing, but it means capturing a wider shot than with one individual. It can be more difficult to light but gives a better sense of personal relationship and interaction. It’s possible to use a smartphone to capture this format. Be sure to turn off the autofocus feature, as it adjusts when hands and arms move closer to the camera. Keep the focus on the face. Give screen space to the arms and torso, as that is where signing usually occurs. Since people sign at differing visual volume, ask the interviewee(s) to sign so that the cinematographer can set the camera width.

With two cameras both the interviewee and interviewer can be filmed, or one camera can be set on the interviewee and the second used for close-ups. The interviewer often sits close to the camera, just to the side. There are different perspectives on where the interviewee should be looking. It is possible to have the interviewee look almost directly into the camera, or be nearly in profile. Thinking about gaze ahead of time will help determine how to position the interviewee. Three cameras can allow for one camera on each person with a third taking in the wide shot. This provides editing options but also creates what can be an overwhelming amount of footage to process. The beauty of using three cameras is flexibility, but it requires significant editing time.

If your interview involves walking or other ethnographic context that requires movement, see the MobileDeaf website. MobileDeaf is an international group of researchers documenting the many ways Deaf people connect across national and linguistic boundaries. See how they use two cameras in their story “Anthropologists and Filmmakers Making Deaf Ethnographic Films” to capture dialogue. Note how one cameraperson might occasionally appear on the screen.

Recording Sound

Several considerations go into determining what, if any, sound should be recorded. How will the sound be used? Who is the audience? If you are planning to add voiceovers, what sound can remain? Does the interviewee or interviewer speak while signing? Are there important soundscapes to record? Is ambient noise of kids playing outside or traffic important? Is there a historically significant sound such as teletype keystrokes? Is laughter important? Do you want to capture the sound of hands slapping while signing? If you plan to record sound, how will you do it without intruding on the signing of the interviewee? How you capture sound will depend on how you plan to use it and how the individuals use their voices. If sound is critical, a boom microphone might be the least visually intrusive, but it prompts questions about why sound is being recorded at all. Be prepared to answer that question.

Filmmaker Zilvinas Paludnevicius and intern Maggie Kopp work on positioning prior to an interview. The camera angle affects how viewers feel. Generally, positioning the camera low enough so that it is pointing slightly up at the interviewee creates a clear, respectful shot.

Accessibility

Access to the interview cannot be an afterthought. Who will be able to watch or listen to the interview? Who won’t? Decisions about access must be made up front as they influence shooting. Will you add captions or subtitles? Captions can be “open” (always on) or “closed,” meaning they can be switched on or off. Captions run on specific lines in the lower third of the screen. They cannot be moved. Captions typically show spoken words along with background sounds or references to music. Subtitles or on-screen text are not locked into a location. Placing them in a corner or across the top or extending from a hand is possible. This takes much longer to do but allows for some creative solutions. The Deaf Jam documentary uses placed text on screen innovatively.

Voiceovers make the interview accessible to non-signing hearing viewers and blind people. They add depth and tone in ways a caption cannot. A skilled interpreter or actor can “voice” the signed message. You may want to try and match the gender or regional accent of the voice actor to the interviewee. For hearing people who do not know sign, watching a Deaf person sign on screen and listening to a disembodied voice can be confusing. Adding a voice that seems to fit the image they see can help. It also clarifies who is talking for blind individuals.

Audio description is an added access feature that briefly, in between statements, tells blind viewers what is seen on screen. Professionals in this field must succinctly describe visual information. Posting a Word document of the script merged with text from the audio description will help make the entire interview accessible to DeafBlind individuals who use a refreshable braille display.

Editing forms a cohesive presentation of the story for all audiences. A Deaf editor or consultant can help make decisions on when and how to cut from one clip to another. For example, a frequent technique is slowing down the lead-in sign for clarity or ending sign for emphasis. Making that type of decision requires language fluency and cultural knowledge.

Jean Lindquist Bergey in a sound booth adding voiceover to footage.

Photo courtesy of Suzanne Scheuermann.

Working with Interpreters

Film production in any two languages is complex. An interpreter creates an insider/outsider dynamic. The interpreting process, no matter how expert the interpreter, alters the experience. There is lag time between each statement. There is lack of eye contact that can cause an emotional disconnect. There are turn-taking issues.

Bilingual documentary film production requires careful teamwork and modification of standard interpreting practices. A major concern for dual language production is loss of fluent ASL when interviewees switch to a more English-based signing, perhaps in response to the interpreter’s language or because the Deaf person is more confident in the interpretation if they sign in English grammatical structure. This will always be a challenge when you have a two-language conversation. The best way to address it is by building a strong team, often including CDIs working alongside certified hearing interpreters.

Interpreters in documentary film production surrender a critical tool–the ability to interrupt to clarify the message. While the camera is rolling, the interpreter is asked not to interrupt when a story is being signed or an extended answer given, even if a portion of the story is not understood. Rather than disrupt a story that cannot be recreated, it is better to wait until there is a pause and then ask for clarification. This requires interpreter(s) and the interviewer to collaborate closely.

Interpreting is an exceedingly complex task and omissions, misreadings, or insertions can occur. Since one interview answer often leads to the next question, the discussion may veer in a direction based on false understandings. Numerous challenges exist when filming or editing an accessible, signed interview or film, such as:

Absent reference. In ASL, a signer may point to a person or set up a place and then refer back to it with a point–similar to saying “he, she, it,” or “that place.” Often the interpreter rightly fills in the referenced person or place. What you then see on tape is the reference to a space, and what you hear interpreted is the specific name of the place or person. A signing editor would know that it is unclear for a Deaf audience. A non-signing editor would know only what they hear.

Place holding and turn taking. Deaf and hearing people hold onto control of the conversation differently and proficient interpreters adeptly negotiate that territory. Deaf people hold the floor visually; hearing people are usually only quiet until they hear a slight pause in the conversational flow. While “voicing” from ASL to English, skilled interpreters hold the hearing person’s attention and prevent interruptions until they can see and voice the full message. They do this in a few ways, most commonly by extension of a word–stretching it out. They may insert the word “aannd” to let the non-signer know that it’s not yet their turn. Understanding Deaf cultural turn-taking etiquette improves the flow of the interview.

Flat tone and decisions based on sound. Often a preliminary interview without cameras is when to determine if the individual would be a good interviewee and engaging on camera. If the interpreter has a flat tone, even if they accurately present the content, it may influence a non-signing interviewer/filmmaker not to include that person in a taped interview. This might happen simply because of the interpreter’s tone or a Deaf individual’s lack of confidence in the interpreter’s voicing, which can slow the pace and flow and make them seem halting and less compelling.

Distracting additions. Some interpreters use colloquialisms or include their own speech habits in voicing. Overuse of the word “like” or “like, you know” or even “like you know, oh my God” might find their way into an interpretation out of habit, not because it was signed.

Edits and selects based on transcripts. Once the signed interview is completed, if transcripts are needed they are typed either from the interpreter’s “voicing,” or transliterated (sign to text without spoken form) from the signer’s statement. Depending on the production team, the transcript rather than the footage may be the basis for film editors to make selects. A skilled bilingual production team makes a tremendous difference in the reliability of the end product.

Voiceovers. Some interpreters sound great; their language flows, but it does not match the signed message. Other interpreters might have a distracting accent or mumbling voice, but they provide complete and accurate information. At times interpreters accurately convey the message in content, tone, and even accent. Once an interview is filmed and the editors are working on using portions of it, they may pull in professional voice actors to restate what the interpreter said. The actors can delete the “uhs” and “mms.” They can add vocal depth and interest. While this adds nothing for the Deaf audience, for hearing people it may make the difference between watching and channel surfing. There are a few dangers. Actors follow a script that may not have comparable emphasis to the signer. For example, “Deaf people started staying home instead of going to the clubs because they could watch captioned videos and TV. It was good! But I missed the fellowship.” Or “It was good… but I missed the fellowship!” The statement could be read in two completely different ways. One suggests the loss of fellowship was regrettable, the other devastating.

Forming a qualified team can ensure accurate interpretation. If possible, hire the same team for pre-interviews, interviews, and editing. There is much more to working with interpreters than can be conveyed in this article. For further information see the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf website.

Following an interview, Barron Gulak views footage as cinematographer Patrick Harris and interviewer Maggie Kopp look on.

Preservation

Care for the filmed interview should be resolved before the camera rolls. How will it be stored? Where will it live? In what format? Will transcripts be searchable? Who will have access? How will the community know it exists? Consider how you will create an edited, accessible, and, if consent is given, publicly available version of the interview.

Film is the only way to show sign and ASL accounts of Deaf life. Interviews can bring little-known stories to the public and enlighten viewers. They can empower individuals and bolster community. There is always an urgency in conducting interviews. People pass on, memories fade. Times change and community life of the past is no longer the reality of today. If a Deaf person agrees to an interview, take time beforehand to consider carefully how you can collaborate with others, particularly Deaf people, to document their stories accurately, and how that recording can live on.

Jean Lindquist Bergey is Associate Director of the Drs. John S. & Betty J. Schuchman Deaf Documentary Center at Gallaudet University in Washington, DC. Bergey, who is hearing, has been a curator, author, and director of multiple documentary projects.

Zilvinas Paludnevicius is a filmmaker with extensive experience filming and editing dialogue in American Sign Language. He taught ASL film production at Gallaudet University and many concepts in this article draw on his course materials. Paludnevicius, who is Deaf, is based in Salt Lake City.

All photos by Jean Bergey unless otherwise noted.

Works Cited

Padden, Carol and Tom Humphries. 2005. Inside Deaf Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gallaudet University ASL and Deaf Studies Department. 2009. Deaf Studies Digital Journal, http://dsdj.gallaudet.edu.

URLs

Oral History Association, Principles and Best Practices: https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009

Drs. John S. & Betty J. Schuchman Deaf Documentary Center: www.gallaudet.edu/drs-john-s-and-betty-j-schuchman-deaf-documentary-center

Council de Manos Know Your Story Interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XJH1hZ15cJ8&feature=youtu.be

Mobile Deaf: https://mobiledeaf.org.uk

Deaf Jam trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muEIiErm0J4

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf: https://rid.org