Artemissia, Yaqui, by Artemissia, 2013; Artemissia with “Yaqui matron” by Edward S. Curtis, 1907 Photos © Arizona Board of Regents. Used with permission. These photos not licensed through Creative Commons.

How do we construct ideas about identity? During the last century photographic imagery has had a big influence on how we perceive people whose backgrounds and cultures differ from our own. More recently, photography has also served as a social justice tool that youth and Native peoples use to establish and express their own identity.

In October 2013, Arizona State Museum mounted Curtis Reframed: The Arizona Portfolios, an exhibit of photographs of American Indians made by Edward S. Curtis during the first part of the 20th century. A successful studio photographer, Curtis traveled throughout the western United States to document what he and the popular media of his time considered “the vanishing race”— Native Americans. From 1907 to 1930, he photographed 80 tribes west of the Mississippi, creating 40,000 negatives, films, and audio recordings now housed at the Library of Congress1.

These stunning portraits have been praised for their beauty and their historical significance but also attacked for being romanticized, colonial, and staged. They are seen both as an incredible documentary treasure and as biased, artistically contrived depictions of Native Americans. The images are, therefore, simultaneously valued and rejected by both scholars and Native peoples.

Most modern viewers who encounter Curtis’s photographs see them as beautiful, realistic portraits of Native Americans in the early 20th century. As art historian Fatimah Tobing Rony notes, viewers of images of other cultures, “do not see the images for the first time. The exotic is already known” (1996:6). Curtis’s photographs fit the image in viewers’ heads of what an Indian looks like. When they learn more about Curtis and about Native life in his time, they might question the validity of the portraits as unquestionable statements of truth. In her book On Photography, Susan Sontag urges viewers to think of photographs as “inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.” She wrote, “The ultimate wisdom of the photographic image is to say, ‘There is the surface. Now think—or rather feel, intuit—what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way” (1977:20).

But the viewer’s bias, as well as how and by whom the photograph is presented, of course, affects that reality. Museum exhibits coupled with extended interpretive programs can help viewers understand this complexity and start conversations about identity, representation, and interpretation. Museums can help facilitate these types of conversations in their interpretive labeling as well as by presenting multiple versions of images in juxtaposition to offer different viewpoints.

To promote a conversation about identity and interpretation around Curtis’s work, in October 2014 Arizona State Museum is opening a complementary exhibit, Regarding Curtis, consisting of works by Native artists created in response to Curtis’s photography. In addition, the museum will mount the exhibit Photo ID: Portraits by Native Youth, created as an outreach project related to the original Curtis Reframed show. Students at Ha:san Preparatory and Leadership School2, a charter high school for Native American youth in Tucson, created the exhibit images under the direction of ASM’s Director of Community Engagement and Partnerships Lisa Falk with Ha:san’s art teacher Koletta Saddleback (Cree). Thirty-‐eight students participated in a five-‐week portrait photography project during which they explored the question, “What is identity?,” and examined how a photographic portrait can be a statement of identity. They considered objects that express identity, studied a variety of portraits, and researched Curtis’s photographs. They then planned their own photographic self-‐portraits that they created in a makeshift studio working together in groups of four students.

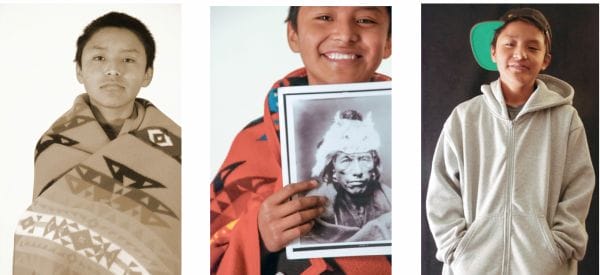

Each student created a series of three self-‐portraits. The first was made in the style of many of Curtis’s photographs in which the subject is wrapped in a blanket or shawl so the viewer sees only the subject’s face. To further the reference to Curtis’s work this portrait is presented in sepia tones, while the next two portraits are in color. In the second photograph the subject is still covered by a blanket or shawl but is holding the Curtis photograph of someone from his or her tribe. In their third portrait, students are depicting themselves as they would like to be seen today. Their images can be seen in the online version of the traveling exhibit Photo ID: Portraits by Native Youth.

In the process of creating the photographs, the students not only learned about photography but also how to question images. They explored expressions of identity and examined their own. Some of their comments collected from short reflective responses to daily writing prompts give insight into their thoughts.

Objects of Identity

Looking at Cultural Markers—objects that reflect a connection to an identity—is helpful when thinking about creating portraits. Koletta Saddleback and I encouraged students to consider choosing an object to include in their portraits. Several chose a basketball and Virginia brought in her sketchpad with the word ANIME inked on it. She wanted to express herself as the anime-‐style artist she hopes to become professionally. Wendel brought in a gourd rattle that his uncle had made for him, explaining that he used it when singing traditional songs. But when we did the photo session, instead he brought a mask that he had made.After reviewing the photographs, Koletta wondered about the appropriateness of the mask. So we asked the cultural teacher, a highly respected elder, her thoughts about Wendel’s photograph with the mask. She explained that it was not appropriate as it was a war mask and their tribe has not been at war for a long time. She spoke with the student about it and he chose to reshoot using the gourd rattle. Most schools will not have a cultural teacher, but your community holds many cultural experts. Don’t be afraid to reach out and ask their advice.

Brayden, Tohono O’odham/Navajo, by Brayden, 2013; Brayden with “Lynx cap” by Edward S. Curtis, 1907

Photos © Arizona Board of Regents. Used with permission. These photos not licensed through Creative Commons.

Nixie commented on how covering up a person takes away unique identity. “[It] made me feel kind of weird because I didn’t get to express myself and who I am. I felt like a blanket was covering who I truly am…I’m more happy and athletic and creative. Being covered is not me. It was a different me, and when I’m not covered I’m myself and independent.”3

George found that by embodying a more stereotyped image of an Indian, he could claim his Native identity. “When I was wrapped up I felt like I was being part of my culture. I also felt like I was very respectful. I don’t think I look cultural to be honest. It felt like I was a famous Native person with everybody around taking pictures.”4

Wendel, in contrast, felt that the blankets took away from the subject’s true identity. “[The photographs of people covered in blankets] made me feel sad because they are not showing who they are. They need to be proud of where they come from and who they are and what their language is—who they represent.”

Timothy enjoyed being able to analyze the historic images and create his own photographs. “It feels fun taking a picture in the different kinds of ways—the past, present, and future—like I’m part of them now.”

Timothy and the other students taking part in this project have always been part of Curtis’s images whether they were conscious of this or not, or they accepted this outsider’s vision of an “Indian” or rejected it. Many non-‐Indians’ ideas of Native peoples are based, perhaps unconsciously, on Curtis’s romantic images. Curtis’s images, in turn, were influenced by the need to sell them to “a popular audience whose perception of ‘Indianness’ was based on stereotypes.”5

The students at Ha:san responded to Curtis’s photographs by commenting on his approach and then shedding it to present themselves, still within the confines of a studio shoot. The three different portraits show an interesting comparison, transition, and transformation. In some series, students look more comfortable covered up; in others, they are obviously happier asserting their own image of themselves. George’s comments about feeling more “Indian” when wrapped in a blanket make one wonder how much his self-‐perception is being shaped by stereotypical and historical images of Native peoples. Interestingly, he appears equally as comfortable in his wrapped portrait as he does in his final one in which he balances a basketball in his hand.

By looking at the students’ three photographs side by side, viewers are nudged to think beyond the surface. They are being asked to think about how they interpret images of Native peoples, as well as to consider what images they already hold in their heads and accept without question as truthful statements about Native peoples. The students’ photographs, as Susan Sontag urged, invite viewers to reflect upon “what the reality must be like if it looks this way” and to examine the intentions and biases of photographers and subjects alongside their own as viewers.

Sontag advocated that viewers open their minds when looking at photographs rather than considering them as evidence of what they think they know about the world. She wrote, “Photography implies that we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it. But this is the opposite of understanding, which starts from not accepting the world as it looks…. The camera’s rendering of reality must always hide more than it discloses” (1977:20-‐1). Her words from 35 years ago still resonate. Viewers need to look at who took the photograph and why, the context in which it is presented and viewed, and what notions we bring to viewing it as we consider how we are reading photographs and making meaning of them. Photographs, and identity, have multiple truths and multiple illusions, which create multiple levels of meaning both to and about the photographer, the subject, and the consumer.

Lisa Falk is Director of Community Engagement and Partnerships at Arizona State Museum at the University of Arizona. She is also a photographer whose work includes portraiture, travel, and documentary pieces. She is the author of Cultural Reporter and principle writer of Bermuda Connections: A Cultural Resource Guide for Classrooms, which guide students in exploring and documenting culture and examining expressions of identity. She holds a BA in Anthropology-‐ Sociology from Oberlin College and an MA in Museum Education from George Washington University. Her portrait was taken by her students at Ha:san School.

Endnotes

- Edward Curtis’s photographs: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/curthome.html

- http://www.hasanprep.org

- All student quotes shared from Photo ID: Portraits by Native Youth, Arizona State Museum website, January http://www.statemuseum.arizona.edu/exhibits/curtis_reframed/student_photo_id/index.php

- George’s portrait can be found here: http://www.statemuseum.arizona.edu/exhibits/curtis_reframed/student_photo_id/georger.php

- Gerald Vizenor quotes Christopher Lyman from The Vanishing Race in “Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist” (2001) http://memorloc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/essay3.html#16.

Works Cited

Arizona State Museum exhibits http://www.statemuseum.arizona.edu/exhibits

Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Accessed online: http://www.susansontag.com/SusanSontag/books/onPhotography.shtml

Tobing Rony, Fatimah. 1996. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham: Duke University Press