Screenshot of the West Virginia Folklife Digital Collection homepage

Introduction

The West Virginia Folklife Collection housed at West Virginia University Libraries holds over 2,500 items of documented fieldwork produced by the West Virginia Folklife Program, a project of the West Virginia Humanities Council. Digital and publicly accessible, such collections can be an excellent resource for educators who are interested in teaching their students how folklife, which includes storytelling, folk and traditional arts, and expressive traditional practices, can spark an interest in or understanding of how our everyday ways of living relate to larger, interconnected topics that affect the world beyond our local communities. Seeing our communities through a folklife archive also has the potential to deepen our understanding of who we are and where we live.

The West Virginia Folklife Collection received the prestigious Brenda McCallum Prize from the American Folklore Society’s Archives and Libraries Section in 2022. This prize recognizes exceptional work related to archival collections of folklife materials produced by an individual or institution. As we are honored to receive this recognition, we want to take this opportunity to offer ideas for how to use this readily available collection in classroom settings.

Portrait of Al Anderson at his shoe repair shop (photo by Emily Hilliard)

About West Virginia Folklife

Founded in 2015, the West Virginia Folklife Program documents, sustains, presents, and supports West Virginia’s vibrant cultural heritage and living traditions. The program is a project of the West Virginia Humanities Council and is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History, which also produces Goldenseal, the magazine of West Virginia traditional life.

About the West Virginia Folklife Collection

The range of stories that contribute to the West Virginia Folklife Collection reflect the diverse communities of our state. There are interviews discussing Appalachian food-ways, such as those with bakers Jenny Bardwell and Susan Ray Brown describing the history and recipes of salt-rising bread that they have collected and studied. Interviews on West Virginia music traditions include those with “West Virginia’s First Lady of Soul” Doris Fields a.k.a. Lady D, who describes the blues and Black music scenes and venues in West Virginia. There are several interviews with participants of the active West Virginia Folklife Apprentice-ship Program, including photos and videos and an interview with 2020 NEA National Heritage Fellow and old-time musician John D. Morris of Clay County. Other collection highlights include documentation of the foodways and community celebrations of the Randolph County Swiss community of Helvetia, recordings of members of the Scotts Run Museum in Monongalia County, and Summers County collector Jim Costa’s collection of 18th– and 19th-century farm tools and objects of rural life.

The West Virginia Folklife Collection became available online in September of 2021 thanks to the collaborative efforts of West Virginia’s first State Folklorist and Founding Director of the West Virginia Folklife Program Emily Hilliard and Interim Director of the West Virginia and Regional History Center at West Virginia University Libraries Lori Hostuttler. The core of the collection includes photographs, videos, ephemera, and recorded interviews with folk and traditional artists and tradition bearers throughout the Mountain State. The collection is original and ongoing, and as we conduct more fieldwork documentation over time, we will continue to add to the collections to preserve stories of those who live here and provide access to those who wish to learn more.

The collection draws from field research of the State Folklorist, other West Virginia Humanities Council staff, partners, and contracted documentarians in collaboration with the documented individuals and communities. This fieldwork focuses on the traditional and vernacular music, dance, crafts, foodways, and material culture of the people of West Virginia, from long settled to new immigrant communities. When using the digital collection, there is an option to “Browse the Collection” and use specific filter terms such as dates, creators, contributors, subject categories, and more to help narrow a search. The collection uses the widely adopted Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) as a formal standard for subject indexing language. While there is the convenient option to type in specific search terms to find exact items, there is also the option to click on “Browse Featured Artists, Practitioners & Communities.” This option leads to a curated list of a variety of topics and interviews with individuals that may inspire further research and expand upon assumptions of existing expressive cultural traditions in West Virginia.

2018 West Virginia Public Educators’ Strike Collection

The following section dives into a subcollection of photographs and recordings taken during the 2018 West Virginia Public Educators’ Strike. It offers a great example of relatively recent events that tie together interconnected themes related to classroom teaching and folklife archives. This collection could be used in teaching contexts on public education, unions, labor movements, and public protest as well as forms of ephemeral material culture like protest signs. In the chapter “The Daughters of Mother Jones: Lessons of Care Work and Labor Struggle in the Expressive Culture of the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike” in Emily’s book, Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore & Everyday Culture in Appalachia (2022), she details a taxonomy of these signs, organized by topic and messaging style, such as “personal testimony,” “union solidarity,” and “pop culture references.” As one prominent trend in strike messaging referenced historical labor struggles in West Virginia and Appalachia, this collection could also augment units on the West Virginia Mine Wars, the UMWA, and Appalachian history and identity.

Striking West Virginia educators rally on the steps of the State Capitol, March 5, 2018.

Photo by Emily Hilliard.

The 2018 West Virginia Public Educators’ Strike

On February 22, 2018, thousands of West Virginia public school teachers and school service employees walked out of their classrooms and schools demanding a five percent raise and, most importantly, affordable healthcare coverage through the West Virginia Public Employees Insurance Agency (PEIA). This initial action resulted in a nine-day statewide strike that “went wildcat” when rank and file educators rejected the deal made between the governor and union leadership. The West Virginia Folklife Collection includes a subcollection of videos, vox pop interviews, recordings of speeches, and over 100 photos made during or about the strike. These materials document the occupational folklore and expressive culture of the labor uprising. Vox pop interviews with striking educators, students, and supporters focus on the educators’ motivations for striking and their struggle for better working conditions, often with the acknowledgement that educators’ working conditions are students’ learning conditions. The photos in the collection focus specifically on the visual culture of the strike conveyed through handmade signs and attire during rallies at the State Capitol.

Striking West Virginia educators protesting at the State Capitol hold signs referencing Star Wars, February 26, 2018. Photo by Emily Hilliard.

Connecting Stories of Traditional Practices to Subjects in the Collection

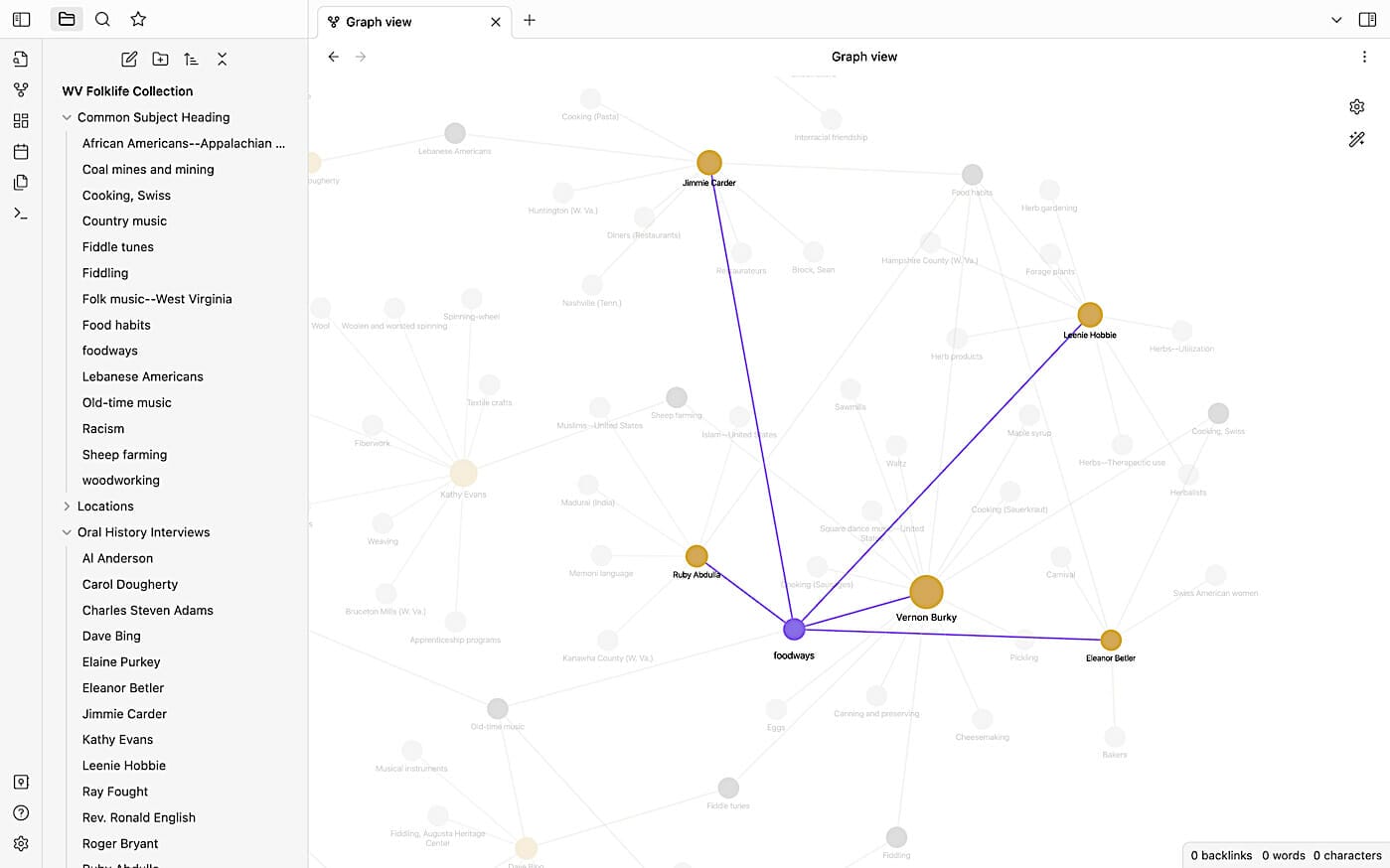

The stories and expressive culture documented and archived in the West Virginia Folklife Collection, such as those of the 2018 West Virginia Educators’ Strike, can convey to students the value of local histories and importance of both documenting and studying community histories and culture. As mentioned, documentation of creative practices used during the 2018 strike can aid classroom teaching when discussing greater themes in history related to labor movements or public education. Making this connection will teach students about contemporary examples of protest and perhaps inspire them to learn more about the history of public education in West Virginia or wherever they live. Students may even discover more themes that arise over the course of their research in the subcollections of the West Virginia Folklife Collection. Below are a few visual webs generated by Obsidian, a notetaking software,* to help illustrate how a selection of individual folklife interviews are thematically connected. The visual cannot express the depth, detail, and nuance of the stories; however, it can present a compelling first glance at how the topics in some interviews relate to important topics in the field of folklore.

*Thank you to Mathilde Francis Lind for giving a workshop on how to use Obsidian for several technology-shy Folklore and Ethnomusicology Department graduate students at Indiana University.

These visuals present connected topics from 16 interviews selected from the “Featured Artists” list. Only 16 are chosen to avoid a cluster of information that would make it impossible to wade through the screenshot visual. The topics are based solely on the Library of Congress LCSH attributed to each interview, not the full interview transcription text. While one can see that each interview connects to another by at least one subject, the people whose interviews are preserved in the West Virginia Folklife Collection may connect over many more topics, including shared creative interests, places where they grew up or worked, and even social bonds.

Note the images illustrate an example of data compilation on Obsidian. Researchers can download the Obsidian app for free online and use the tool to organize data and notes.

The gold nodes represent a single folklife interview while the light gray nodes connected to the gold and branching off in different directions represent their various LCSH. The dark gray nodes represent shared LCSH, revealing shared themes among individual experiences expressed in the interviews. When using Obsidian, the graph view is animated; it shifts and rearranges so the viewer can consider various degrees of isolation or connection between themes. Visualizing data and notes helps to inspire new ideas and identify connections that one may not have considered. Students are encouraged to try the software, experiment with connections and data, and explore the movement of the animated graph view.

According to the Library of Congress, “foodways” is a variant of the LCSH “Food Habits.” In this visual, the commonly used term among folklorists, “foodways,” is highlighted to show clear connections over food traditions and sharing stories about food and community between the following interviews in the collection: Ruby Abdulla (Kanawha County), Jimmie Carder (Cabell County), Leenie Hobbie (Hampshire County), Vernon Burky (Randolph County), and Eleanor Betler (Randolph County). Please note again that this visual is a snapshot of a few select interviews with individuals who live across the Mountain State and are not the only interviews in the collection that share a common connection over “foodways.”

The purple node is “foodways” and shows connections to gold nodes—folklife interviews.

In this visual, the light gray nodes are filtered out so only the dark gray nodes representing shared LCSH are viewable in connection to the artist and practitioner interviews in gold. A researcher can certainly make additional connections and learn more about how these individual stories relate, which may be a compelling project for students learning to conduct research and analyze themes.

Visualizing data can help students understand the connections between the past and the present, between cultural groups and individuals, and between stories in an archive and stories they hear shared every day. Students should be encouraged to research and interpret themes they identify in archival collections and consider ways that they can conduct creative projects using these themes. They can create poems, songs, zines, or short films after reflecting on the themes and stories they find in archival folklife collections. Folklife collections such as the West Virginia Folklife Collection offer students an opportunity to learn about expressive cultural traditions in their own region and may encourage them to think critically about the practices they carry on in their own communities.

Jennie Williams is the West Virginia State Folklorist and directs West Virginia Folklife Program, a project of the West Virginia Humanities Council. She is a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at Indiana University Bloomington (IU) and holds an MA in Folklore and Ethnomusicology from IU. ORCID 0009-0007-0336-0633

Emily Hilliard is a folklorist and writer at Berea College. She is the former West Virginia State Folklorist and Founding Director of the West Virginia Folklife Program. She was a 2021–2022 American Folklife Center Archie Green Fellow for a project documenting the occupational culture of rural mail carriers in Central Appalachia and serves on the board of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. She is also the co-founder and co-owner of the feminist record label SPINSTER. Her book Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia, a finalist for the Appalachian Studies Association’s Weatherford Award, was published by UNC Press in 2022. She is also co-author of 55 Strong: Inside the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike. Learn more about her work at www.emilyehilliard.com. ORCID 0009-0004-6464-6318

URLS

West Virginia Folklife Collection https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu

West Virginia University Libraries https://library.wvu.edu

West Virginia Folklife Program https://wvfolklife.org

West Virginia Humanities Council https://wvhumanities.org

Brenda McCallum Prize https://americanfolkloresociety.org/our-work/prizes/brenda-mccallum-prize

Goldenseal Magazine https://wvculture.org/discover/publications/goldenseal/

Jenny Bardwell and Susan Ray Brown https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=Jenny+Bardwell+&+Susan+Brown

Doris Fields a.k.a. Lady D https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/?f%5Bcreator_sim%5D%5B%5D=Fields%2C+Doris

West Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Program https://wvfolklife.org/folklife-apprenticeship-program

John D. Morris https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=John+D.+Morris

Helvetia https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/?f%5Blocation_sim%5D%5B%5D=Helvetia+%28W.+Va.%29

Scotts Run Museum https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/?f%5Blocation_sim%5D%5B%5D=Scott%27s+Run+%28W.+Va.%29

Jim Costa https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/?f%5Bcontributor_sim%5D%5B%5D=Costa%2C+Jim+%28Banjoist%29

2018 West Virginia Public Educators’ Strike Collection https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=West+Virginia+Teachers%E2%80%99+Strike+2018

Obsidian app https://obsidian.md

Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia, by Emily Hilliard https://uncpress.org/book/9781469671628/making-our-future

“Food Habits” https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85050275.html

“Foodways” https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/?f%5Bsubject_sim%5D%5B%5D=foodways

Ruby Abdulla (Kanawha County) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=Ruby+Abdulla

Jimmie Carder (Cabell County) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=Jimmie+Carder

Leenie Hobbie (Hampshire County) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=Leenie+Hobbie

Vernon Burky (Randolph County) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=Vernon+Burky

Eleanor Betler (Randolph County) https://wvfolklife.lib.wvu.edu/catalog?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=Eleanor+Betler

55 Strong: Inside the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike. Elizabeth Catte, Emily Hilliard, and Jessica Salfia, eds. 2018. https://beltpublishing.com/products/55-strong-inside-the-west-virginia-teachers-strike