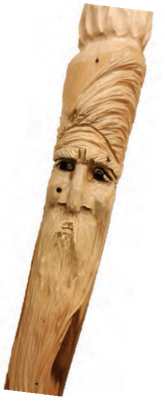

The woodcarving is by “Clark,” a participant in the workshop sessions of the Community Stories Writing Workshop at Shelter House, Iowa City. Photo by Rossina Zamora Liu.

I. Lawn Chair as Trope

When Long moves into his next home, he will take only the things that matter most: his television, a Sony analog box that he and his wife purchased when they were married; his stereo, two giant Sony boomboxes, or blasters, from the ‘80s; and his television couch, which actually is a plastic lawn chair that he resized by sawing off half the legs to fit his height. These are the items that fill his living space, wherever he settles. Together and separately they carry with them memories—stories—invisible to the human eye, although perhaps not to the human heart.

Artifacts collect and tell stories. This, folklorists have long known. One broken Sancai Chinese vase, for example, from the Tang Dynasty at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, DC, speaks the cultural aesthetics of the time, as well as the availability of material and resources with which the piece was crafted. From there, we reimagine the interior of a Chinese aristocrat’s home. We see the nobleman admiring the ceramic. He is inspired by the three-color pottery—yellow, green, and white—before his eyes, and in this moment of elation, he tells his wife that when he dies, he would like the vase in his tomb—along with her and their servants.

And why wouldn’t he?

In earlier times pottery of this sort was commonly used for burial. The vase offers us a sneak glimpse of religious beliefs, of social class constructions, and of ways in which ancient Chinese aristocrats legitimized their power (Bronner 1986; Prown 1982; Sims and Stephens 2005; Toelken 1996). Folk objects can “remind us of who we are and where we have been” (Bronner 1986, p. 214) and, for that matter, where we are going—as individuals, as a culture. What are cultural artifacts, after all, but the objectification of human ideas and values (Bronner 1986; Kouwenhoven 1964, 1999; Prown 1982; Schlereth 1985)? Of our mortality, our significance, our stories? And these stories, our stories, are shape-fluid and because they are, they possess infinite possibilities of forms aside from the initial artifact: forms that become visible in other ways with the help of the beholder who composes them, writes them, in fact, transforms them.

Each time Long sits on his plastic lawn chair, puts on his Bose headphones, and turns on a Vietnamese music video, for instance, he also feels the heaviness of that big Sony television box resting on his five-foot frame. He recalls the time when he and his wife forced it up the stairway of the apartment complex. The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade was the next day, after all, and what could be more American than to watch it close up via Japanese technology? As snapshots of the parade flash before him, he hears the drumbeats from high school bands marching down 38th Street and Herald Square in New York City. The band’s percussions blur with a woman’s high-pitched voice stretching out a Vietnamese ballad from the music video. He feels the vibrations of his lips humming or, perhaps, of his left foot tapping, dancing, along to the syncretic sounds. In these moments, he experiences the chair not just as a piece of furniture, but also as a material object that is physically, metaphorically, and sentimentally re-crafted into memories about a time that once was, when he and his family tried to live up to American conventions. In these moments, his heart aches. His mind races. He exhales. Then he puts pen to paper, and he writes.

Like all fine arts, writing gives form to things seen and unseen, transforming them into strings of words that, when woven together, materialize into possibilities not yet conceived, or at the least, not previously acknowledged or remembered. Writing, thus, gives shape to stories that the artifacts carry and in so doing reshapes the artifacts themselves. In “shifting the shape” of each artifact, thereby layering meaning to it, writing also changes the dynamics and exchanges between the writer and the object. Where we once experienced a story through its artifact, for instance, we later experience it as a poem, a song, or both. A plastic lawn chair, thus, is no longer a plastic lawn chair, but a plastic-lawn-chair-poem montage about a life.

Indeed, writing has the power to turn objects into stories and stories into objects. Writing is a double act of alchemy. Writing is a double act of magic.

II. Magic in the Drafts

Writing is a craft before it is an art; writing may appear magic, but it is our responsibility to take our students backstage to watch the pigeons being tucked under the magician’s sleeve.

~Donald M. Murray, A Writer Teaches Writing

So how does the magic work? How does a writer turn an object into a written story? How does that story reshape the object? The answers are less mysterious than the questions themselves. The short of it is: craft by way of drafts—lots of them. The longer discussion, of course, is much more involved, but one that demystifies the alchemy nonetheless and makes accessible the magical art of writing.

Pulitzer Prize winner and writing teacher Donald Murray tells us that so much of writing seems magical because we only witness the end product. We don’t see the many drafts that writers must revise, or as he refers above, “the pigeons.” We don’t see the different strategies that writers consider during their processes. We don’t see the honing and persisting and experimenting during their revisions. We don’t see the craft. And particularly for writers who are not necessarily comfortable on the page, writing can seem dauntingly impossible with limited choices: the blank sheet of paper and the ink-filled pen, or the computer monitor and the perpetually blinking cursor. These writers don’t see outside their options. They don’t see the infinite shapes of the artifact.

As writing teachers whose teaching careers are influenced strongly by folklore, we see our roles as enabling writers to look carefully and to write about what they see (Geertz 2003 and 1988; Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater 2012). One way we do that is to invite them to engage with personal, material objects. Artifacts, as we have discussed, can serve as entry points into composition, giving writers the reflective distance they need, and the opportunity to be expert on something while enhancing their own thinking. Rather than writing about a generalized feeling and/or other abstract ideas, for example, artifacts can stimulate writers’ memories to do the reflecting; the reflecting can inspire writers to do the inferring; the inferring can connect writers to do the reshaping—of object, of story, of meaning. Artifacts can, thus, offer writers the details to do the showing.

“What do you see when you look at this artifact?” we ask writers. “A ‘big glob’ doesn’t tell readers enough. What’s big and globby to one person isn’t to another. What about color? Size? Shape? Movements? Measurements?”

“What do you smell when you take a whiff of it into your nose? Where else have you smelled something similar or something different? What do you recall when you smell this scent? ‘Yucky,’ for instance, doesn’t offer enough details. Does the smell take you to the memory of a place? A scene? Food? Drink? Something in the natural world?”

“What about sound? What do you hear? ‘A noise’ that makes you think of what?”

“What do you taste? Or perhaps what taste do you recall, do you imagine, do you think of? ‘Delicious?’ Like what?”

“And what about touch? Touch it. Work your fingers through it. What does it feel like physically? What does it feel like emotionally?”

Of course, inviting writers to use their five senses to engage with material objects is not new. It is one tool that allows writers to draw on their own experiences and knowledge to tell the story from their points of view. After all, everything has already been written but not necessarily in the way that each writer would, or could, write it. The five senses enable writers to narrow more easily in to the specifics—their specifics—to portray and translate “big” abstracts into vivid, tangible illustrations.

Mark Twain once said, “Don’t say the old lady screamed. Bring her on and let her scream.” What he means by this most fervent plea, of course, is the old writing cliché, “show, don’t tell.” It is the elixir of all magical writing—for every writer, for every storyteller, for every folklorist. We depend upon this wisdom to help breathe life into stories. We say, “Don’t tell people: ‘The fireworks were awesome.’ Show them: ‘Each boom exploded silvery greens, blues, reds into the dark, warm night; sulfured smoke seeped over the ocean.’” For writing that shows is writing that performs and thus invites the reader—the audience—to participate. When readers participate, they are talking to, and with, that performance. They are making meaning of it, relating to it, claiming parts of it, and importantly, they, too, are performing the magic (Abrahams 1992; Bauman 1984, 1992; Briggs 1988; Turner and Schechner 1988).

It may be helpful, too, to remind writers that the “writing” is already inscribed inside these objects; hence, when we are taking pen to paper, we are in essence interpreting it, translating it onto another medium. The stories have been collected and thus already live inside Long’s lawn chair and television set and boomboxes, for example. To tell those stories, he must bring life to them in a way that allows others to witness them also and, possibly, participate with him in making sense of them.

Granted, not every writer will compose with equal facility, at least not with pen and paper, keyboard and monitor. Many will prefer to be oral historians of their material artifacts. Some stories are best conveyed and performed orally (Bauman 1992; Lord 2000); some stories do not want to be in written form. But for those that do, the process to transport and thus transform them from object to written medium can, and will—and should—vary with every writer. As writing teachers, we must work to understand such variability so that we may help writers uncover the hidden layers that are not so obvious, enabling them to write about their own histories, the very histories they sometimes do not readily see. Varying the gateways for writers’ entries into composition is not only useful, but often necessary.

The truth is, whether they are in a museum, a graduate program, a public school classroom, or a community program, there are many writers who do not easily warm up to the idea of writing at the onset—writers like Clark, a U.S. Army veteran in his mid-50s, who had not picked up the pen since 10th grade until he discovered wood spirits inside a writing workshop at a homeless shelter; like Anna, a high-performing doctoral student who could not see beyond the academic jargon of English literary critique until she rediscovered (and researched) a version of Snow White and Rose Red in her grandmother’s garage; or, like Nikki, an English Language Learner student at an urban high school who did not see the purpose of writing or math, let alone writing in a math class, until she discovered the ratio of fat to meat in pepperoni. Although Clark, Anna, and Nikki are three different writers from three different generations in three different contexts with three different writing processes, they are writers who also share resistances to writing stemmed from an unchanged writing culture of red-ink-pen explosions and narrative “I” taboos. Our approaches to working with them have entailed many process-oriented strategies, but one of the most successful is indeed the object biography.

In the following section we offer portraits of these writers: Clark, Anna, and Nikki. Although neither of us worked one-on-one with all three writers (as Clark worked with Rossina through a writing workshop at a homeless shelter while Anna and Nikki worked with Bonnie in a graduate writing class and a high school math class, respectively), we collaborated and consulted with each other regularly on using objects to facilitate their writing processes. The rest of this essay is our collective reflection on how artifacts gave the writers entry points into their stories, as well as how writing enabled them to reshape the artifacts themselves. For the very things that shaped their writing indeed became the very things that were shaped by them. We conclude with our favorite writing exercises.

III. Three Portraits

…at the end of the day, we’re part of a long-running story. We just try to get our paragraph right.

~Barack Obama to David Remnick, The New Yorker

One Veteran Composes the Things He Carries: Magic inside a Homeless Shelter

We begin with a portrait of “Clark” because his resistance to writing is one of the more common kinds that we see as teachers. Like many members who participated in the Community Stories Writing Workshop at the local homeless shelter in Iowa City, a writing group that Rossina founded in fall 2010 with, and for, the community, Clark did not consider himself a writer and preferred instead to be called a storyteller, deeming the designation more accessible because it did not, for him, carry the weighted judgments of grammar. “If you ask a guy to tell stories, he can just recall it and tell it the way he talks,” he said. “But if you ask him to write a story, he has to think about spelling and punctuation and all that stuff that you get graded for, and he’s like crap. How do I do that? I’m a storyteller because no teacher can tell me that I’m not.”

And indeed a good storyteller he was. Clark could tell a story about anything—the different kinds of wood in the Midwest, the different things you could do with morel mushrooms, the different kinds of pens you could get for free (mostly from banks)—and capture full audience attention. There was a rhythm in his delivery, an intention in his pauses, a naturalness in his timing. There was an awareness of voice, of persona, of audience—there was a performance (Bauman 1992; Lord 2000). Still there was also hesitance, if not avoidance, when it came to writing, the activity for which the group was intended and named.

Until joining the workshop, Clark said he hadn’t “picked up the pen since the 10th grade—except to endorse a check, which is never, or write a check to pay bills, which is more often than ideal.” Ranked 452 out of 453 in high school, writing, for Clark, was a practice that happened only in school, in the same way that writer was a term that teachers granted only to students without red marks on their papers. He, like many writers with whom we’ve worked, did not initially see writing as a way of being that belonged to him. And yet, what we want to underscore about him is that he was also the same person who, after discovering his voice on the page, would drive out to his storage unit at two o’clock every morning, set up a battery-run lamp atop a few boxes, and compose short stories and essays into dawn. As a client of the homeless shelter at the time, writing, he said, was his “only escape and salvation.”

Of course, Clark’s discovery of self as writer did not happen overnight. For the first several sessions he would respond to the writing invitations, or prompts, only by way of talk. Regardless of the prompt, Clark would return to the walking sticks he carried and tell the writing group about his carvings. The essay below about wood spirits, for example, was the first he narrated orally, and one that he continued to retell for several sessions.

Some people see this face and think it’s Santa Claus, but it’s not. It’s a wood spirit and according to German folklore, they are protectors—guardians—of the Black Forest. They watch over the woods and protect it from fire destruction. They also represent good luck and such. I wear one on my neck, too, but usually I carve them onto walking sticks….

It used to take me a whole day to carve a face like this, but then I met Jim. Jim had this huge shop and that’s all he did—make and sell walking sticks….he showed me how to do it more efficiently. The guy could carve these things in 20 to 30 minutes. I’m a little slower, although what used to take me a whole day, now only takes me about 45 minutes. Before Jim, my mushrooms also used to be all the same, just a bunch of patterns in a row. But now, they have shape and I have people asking if I attached some plastic mushroom to the stick. They just can’t believe that the morels are part of the stick—it’s wood. I’ve carved these things over a hundred times, and you know what? None of them are alike.

I’m not sure why I’m telling this story other than to say carving represents an important part of who I am and what I’ve worked hard for…. The act gives me time to think through things. It’s also soothing…. I don’t want to have to mass produce these things. I don’t want to not care about the details. I don’t want it to not be therapeutic. I guess you can say, it’s really about the time and the craft. I’ve done it for eight years so far.

This reminds me of that story about Pablo Picasso. He was sitting at a bar one day and some guy came up and asked him if he would draw something for him on a piece of napkin—sort of like an autograph. So Picasso drew something. I don’t know what it was, but anyway, when he was done he handed the napkin to the guy, and the guy was all happy. “Hey thanks! That’s pretty cool,” he said. Then Picasso said, “Hey wait. I want $10,000 for that.”

“What? Why?” asked the guy. “It only took you 5 to 10 minutes to draw that,” to which, Picasso said, “No. It took me 40 years.”

That’s the best way I can explain it—the craft of woodcarving. It’s like that.

It was evident that Clark was extremely proud of his craftsmanship. Woodcarving was what he knew best and it was a topic about which he was most comfortable talking. What’s noteworthy during these deliveries was that, as he narrated the story, he would run his fingers along the indents of the carved faces, and sometimes embrace the sticks, bringing them closer to his side—reading and reflecting on the sticks as he went along by way of touch and sight.

As writing teachers we recognize that these are opportunities for deeper narrative exploration. Posing sensory questions could help writers potentially uncover the other layers of meaning behind the objects and, importantly, their stories. For Clark the questions included:

“What did the first wood spirit look like when you carved it?”

“If you closed your eyes and opened your ears, what do you hear when you think about these wood spirits?”

“Of all the sticks you’ve carved, which was your favorite and why?”

Each time Clark answered various renditions of these questions, he offered seemingly different answers but those embodied similar themes. For example, to the question “What did the first wood spirit look like?” Clark’s answers ranged as follows:

“It wasn’t the first one I made, but it was one of the first. The stick was ugly and was very rough, but I was proud of it.”

“It wasn’t of a wood spirit. It was a mushroom. You couldn’t tell though because it looked like a hot dog. I made it for my daughter and it was one of the few things we did together.”

“It was on a short walking stick because my daughter was very young at the time. I don’t think she cared that it didn’t look like a mushroom.”

Each of these answers suggested a kind of nostalgia and sentimental relationship that weren’t evident in the story he told orally about the wood spirits. There were layers yet to be uncovered and with each conversation, or what writing teachers call “writing conference,” Clark went a little more in depth about his relationship with his daughter.

To facilitate his writing processes, the sessions of Clark talking about the wood spirits and reflecting on the sensory questions were audio-recorded (by Rossina). After multiple sessions, when it seemed as though he had exhausted what he could orally compose about the sticks, he was invited to listen to the recordings and transcribe the parts that he felt were important to convey in writing.

What was interesting, or magical, about Clark’s process—the movement between orality and written form—was the narrative shifts that occurred through the act of transcribing. That is, in writing it, he started revising his story, connecting different memories and sentimental details to it, shaping it into something other than about wood spirits, morel mushrooms, and Picasso. Eventually, he composed a written draft about the first stick he carved for his, then, five-year-old daughter. The story centered around a father-daughter walk through the woods, but the emotional layer was about his regret for not having spent more time with her.

Of course this process entailed many drafts through writing prompts and exploratory questions about artifacts—about the carvings on the sticks, about the various written drafts, about all of them. It also entailed a lot of encouragement because, again, initially he did not see the compositional potential in his orally articulated story and was rather resistant to putting his thoughts onto the page. As suggested, part of his hesitation stemmed from a history with teachers who overlooked strengths, be it because of standardized testing, expectations of correctness, strict attention to rigid models, or simply lack of knowledge about writing; we don’t have to go far to understand why red pens are sold in bulk.

And part of it, too, is that writing is often overlooked—forgotten—as a folk practice in our culture, even though early writings happened on walls of buildings, on textiles of clothing, and on surfaces of objects (such as those displayed in homes and museums, for instance). As a consequence, writing has become inaccessible; the very art and craft that once belonged to the folk has, in many ways, become “gentrified.” And so as teachers our role is to remind writers of the folklore-writing connection and thus, their familiarity—and right—to writing.

Not only did Clark’s story about wood spirits reveal his knowledge of woodcarving and folklore; it begged questions that he knew answers to: “Why woodcarving?” “Why do you carry these sticks with you?” “What is their significance to you and your life?” “What was the first stick you carved, that you were most proud of?” “And why?” These questions were opportunities—invitations—for him to draw from his own knowledge and to build on it. They offered him a way to explore narrative possibilities behind the objects and his carvings.

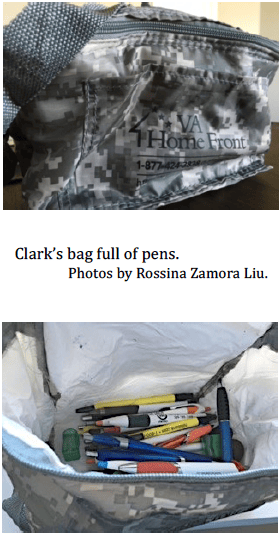

Clark would eventually go on to write many stories: an essay about local heroism, loss of his father, memories of his first horse. These stories were therapeutic for him to tell, as they were transformative for him write. Over time, he also collected and carried additional artifacts, those reflective of his newly found storyteller-writer identity, such as black and white composition notebooks because he assumed, “the kids still use them in language arts class.” Or those free pens he collected from various venues, mainly local banks and job fairs. One time, he came into the workshop and threw a camouflage fanny bag full of pens onto the table. “Don’t get all excited, everybody,” he said. “You can have these for the same price I paid for them.” And then after he distributed the pens to each member, he turned to the facilitator (Rossina) and said, “I figure I’d help you out a little. You always seem to run out of pens. Now, you know it’s because I’ve been stealing them from you.”

It is hard to believe, sometimes, that this was the same person who once said he would never again pick up a pen other than to endorse a winning lottery ticket. Because here is a gifted storyteller: someone full of wit, humor, and presence; someone who, when invited to reflect on artifacts, observed sensory details and composed meaningful narratives about his own history. Here is a craftsman, who, from woodcarvings on walking sticks made visible the stories living inside them, and they, these stories, in turn, made visible the writer living inside him—by way of the composition notebooks, by way of the bag of pens, by way of the things he carried. Here is a storyteller who, indeed, is very much a writer, an alchemist, a writer-alchemist in his own right.

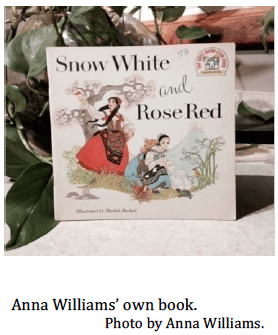

One Graduate Student Composes an Object Biography: Magic inside Pandora’s Box

We move now to another writer-alchemist. Anna, a soft-spoken graduate student in English, is a young woman in her mid-20s who came to her PhD from a successful college career in the American South. She is a lifelong reader, happy to have the privilege of choosing literature as a specialty. But she had lost her way in the thick forest of academic jargon in English literary critique until she rediscovered and researched a version of Snow White and Rose Red in her grandmother’s garage. Other than textbooks and articles about literary critiques, Anna didn’t need to carry much with her into the classroom, at least nothing that could be seen with the naked eye.

But in our seminar, Family Stories, Oral Histories, Portraits, and Object Biographies, she studied this one book, a beloved artifact of her past and an homage to her grandmother. As a student of literary theory, Anna had never taken a writing course, nor did she know much about ethnographic research or folklore as a discipline. She was fearful and admitted it to her classmates. The assignment to write one carefully researched essay—and work on it all semester in short preparatory writing—was terrifying to her.

She’d never written “personal stuff” before, she said. At first she was resistant and quiet, ready to read whatever we assigned, but afraid to write. After several exercises in class, she found herself stuck on one strong memory about a dusty book on an empty bookcase in her grandmother’s garage: “a beautifully illustrated version of the Grimms’ version of the fairytale about two sisters, one fair like the snow and the other ‘dark and beautiful as the red roses.’ Granny would read this book to my cousin Abby and me, always sure to point out that we, too, were fair and dark just like the sisters….I flipped through the frayed pages with reverence, wondering how on earth such a fragile thing could have ended up out here…”

Anna’s research led her in many directions, including her French-German heritage and her hometown in Tennessee. Her final essay contained three German subheadings (Die Steigende—the rise/climb, Der Tod—the demise, Das Ewige Leben—the life), a metaphor for the story she was telling as well as her own position as a student.

She collected data from multiple sources: telephone and live interviews with relatives, her now deceased grandmother’s written memoir, an inventory of her southern family homestead and its town’s historical society. She pored through other similar tales (Greek, biblical, and American), histories of 19th-century American bookselling and distribution, her own family’s longtime business’s loss to a big-box store. The course paper had 15 scholarly references from folklore and history and, of course, her memory. “Granny’s own stories were not unlike fairytales,” Anna wrote, “they often included pirates and ghosts and antebellum princesses in plantation castles” (Williams, 7). “For Granny, history was just an opportunity to tell a good story—to create an easier, brighter somewhere else as if by magic” (Williams, 7).

It was her engagement with the actual object that brought her research to life. In her description of the book’s first page, Anna writes, “Against the backdrop of a quaint hearth with glowing fireplace, Rose-Red, the dark-haired, pluckier sister, stands in the foreground of the page, unlocking the cottage door and pulling it open with dainty pinkies extended. On tiptoes in her Bohemian clogs and aproned dress, she smiles in anticipation of the friendly face she expects to meet as snow and wind rush through the cracked door. Her sister cowers on a stool behind her, reaching out to their mother who is just standing up from her chair. The mother, also dark like Rose-Red, is illustrated with her thumb, index, and middle finger pointed upward, indicating she is mid-speech. ‘Go and see who is there,’ she says, ‘It may be a traveler who is cold and hungry’” (Williams, 2). Anna explains the trope of the disguised stranger at the door, recognizing familiar variants in the Bible, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and other folk traditions, referring to Walter Benjamin’s concept of “cross-fertilization” in time and space. It stands as a metanarrative Anna reminds us in her essay, which influences our environment through the artifacts that we find and the stories we tell about them…. When we think about it at all.

Then the essay returns to Anna’s book. “At the precise moment of the visitor’s anticipated entrance, the girls’ mother has just been reading to them…..a book flutters to the ground, suspended in mid-air where it has just slipped from the startled mother’s hand. It is a metanarrative moment in which the story, in effect, calls attention to itself as a story” (Williams, 10). Anna continues to summarize the book’s story, its variants in other historical contexts, the universal message about trusting strangers, and the rewards of good deeds. “So in the end,” Anna concludes, “maybe it doesn’t matter if Granny’s stories were as much fairytales as the jewel-colored book in her garage…. Maybe we’re not supposed to believe in them at all, but only what they stand for….”

Anna’s love for learning and scholarship is clear and passionate in her essay, but it is the personal connection to her grandmother, to her roots, to that dusty “jewel-colored book” she recovered in the garage after all those years, that makes her account sing to a reader: of history, economics, traditional folk motifs, religious and cultural heritage of both the southern U.S. and Germany. Anna’s linking of intellectual passion and personal past to her scholarship contributes to her growth as a writer.

We know that artifacts serve important functions for examining details in cultural stories, and many recent initiatives in the cultural history of objects show scholarly recognition of that (Halton 2011, Kurin and Clough 2013, MacGregor 2011, Sunstein and Chiseri-Strater 2012). Even TV programs like History Detectives, Antiques Roadshow, and American Pickers offer eloquent personal peeks into entire cultural histories—of both owners and appraisers/analysts, offering inventories of human ingenuity, historical insight, and even a kind of hope.

Creating an Object-Centered Writing Classroom

The course recognizes that objects and living interviews are not only metaphors but also primary sources, often the best way to unwrap the stories hiding inside. Over time, we know graduate students’ writing, like Anna’s, will stiffen and clutter because of pressure to sound “right.” Authenticity and voice disappear under years of academic obedience. We wanted students to see that with authentic but no less rigorous writing, academic research makes for enjoyable and engaging writing—and reading.

The course website posted objects whose cultural history and value were not traditionally academic but were packed with meaning and history and, yes, academic possibilities. A search about an object might yield new knowledge, and the information might come from unlikely sources.

We posted an example from the National Public Radio (NPR) series Planet Money Makes a T-Shirt, which itself evolved from a sourcebook, Pietra Rivoli’s The Travels of a T-Shirt in a Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Market, Power, and Politics of World Trade. Two reporters, Jacob Goldstein and Alex Blumberg, along with the Planet Money team, created a five-part radio documentary on the political, economic, social, and ethical complexities involved in a contemporary enterprise when NPR commissioned a T-shirt. The nuances are astonishing.

There are movies, too, about artifacts; we’re sure everyone has a favorite. The Red Violin (1999) is a good example that a good object “study” is really about an idea. In the last two paragraphs of Roger Ebert’s eloquent four-star review, he explains it’s an homage to an idea ABOUT an object. First, he outlines the main vignettes of the narrative. But then he writes, “A brief outline doesn’t begin to suggest the intelligence and appeal of the film. The story hook has been used before. Tales of Manhattan followed an evening coat from person to person, and The Yellow Rolls-Royce followed a car….Such structures take advantage of two contradictory qualities of film: It is literal, so that we tend to believe what we see, and it is fluid, not tied down to times and places….The Red Violin follows not a person or a coat, but an idea: the idea that humans in all times and places are powerfully moved, or threatened, by the possibility that with our hands and minds we can create something that is perfect.”

Paper Clips (2003) is a very different example. Middle-school students in Tennessee learned that paper clips had been developed in Norway during WWII as a symbol of solidarity against the Nazis. They wondered what a collection would look like, one paper clip to honor each victim, and where they might house this collection. The film tracks their project, online, in the media, and by word of mouth, as it crosses the world and results in a riveting memorial museum on the school grounds: 11 million paper clips housed in a donated authentic German railroad car. In the film, we meet survivors, journalists, educators, and the students themselves as the project about a paper clip becomes a visual essay about diversity and intolerance.

Since this was a graduate course, we indulged in a lot of nonfiction reading. We each found and chose one published essay to share, but everyone read Jamaica Kinkaid’s personal meditation about colonization through objects, “On Seeing England for the First Time”; Pico Iyer’s take on the English in India, “A Far-Off Affair”; Lars Eighner’s “Dumpster Diving”; and Garrison Keillor’s “Ball Jars.” We explored books about artifacts, some in detail, some by review: Agnes’s Jacket: A Psychologist’s Search for the Meanings of Madness; The Coat Route: Craft, Luxury, and Obsession on the Trail of a $50,000 Coat; Stuff Matters: Exploring the Marvelous Materials that Shape Our Man-Made World; A British History of the World in 100 Objects; the Smithsonian’s version, A History of America in 101 Objects; as well as Bonnie’s book, FieldWorking: Reading and Writing Research.

The real proof of the value of “object biography” was in the students’ work. Their 17 essays ranged from a regional history of a recipe book passed to four generations in one student’s family, to a full analysis of Twitter’s thematic threads, to an audio essay about personal descriptions of “love.” The seminar offered an education of a different sort to a long tableful of conventionally educated students.

One High School Student Composes Ratios with Pepperoni

Finally, and with contrast, we introduce you to Nikki, a bouncy sophomore in an urban high school. She wears her school ID sticker on her thigh, just above her carefully slit jeans. Although she is a typical American high schooler, her school attaches multiple labels to her that belie her personality: “underperforming,” “ELL,” “low achiever.” An immigrant from Central America, she’s a second language English speaker with a home life both peppered by gang shootings and nourished by loving family. In class, she primps her long hair, sits too close to her best friend Margretta, checks her petite frame regularly, but enacts bold leadership abilities. She is a natural collaborator, and her math teacher allows her to solve problems in concert with her classmates. She approaches tasks in geometry with a smirk, an eye-roll, and distracted attention. But she completes them with a creative spin. Although she’s had low test scores, she’s an engaged learner.

On a day we observed, her assignment was about circles. The students were learning to use iPads, a funded school program that offered one per student. They knew how to use the iPads to take standardized tests and use online tools to solve geometry problems. But their teacher wanted them to learn the power of research and was interested in “object biographies” in his class. “Where do you find circles? And what do they tell us?” His assignment was simple: “Create a slide, write a sentence.” Other students chose artifacts like wheelchair wheels, the peace symbol, a bathtub sponge, airplane tires, basketball hoops. Everyone chose a cultural artifact.

Nikki smirked at the assignment and observed loudly that pepperoni is both a cylinder and a circle. It was a joke at first, meant for her seatmate who was researching spiral clocks. But within an 80-minute double class period, she eventually created her image (seen on the right). During the process of her research, Nikki articulated the differences between a cylinder (the whole pepperoni) and a circle (one slice), and the ratio between muscle (meat) and fat. She discovered that the price of pepperoni depends on that ratio; it goes up when there’s more meat and less fat. Her revised slide illustrates all that thinking and writing.

Six months later, during another research visit, we saw that Nikki had spent time documenting artifacts that appear in math problems, and she was more adept with the computer. She confronted a problem about trolls and barrels of honey. Using a “mind map” program, Nikki designed nine separate but connected stations on her mind map, writing about her solution process over 20 minutes. “I tried to figure out what is hidden in the problem that could give off the answer…. I started to play around and then decided to draw trolls….I switched the half barrels and the empty ones…with Margretta’s help I figured it out…then I ended up getting it right so I was amped because I actually got the answer.”

Nikki articulated her thinking processes as she engaged with artifacts. Whether it was pepperoni or trolls looking for honey in a barrel, she was able to see the value of persistent inquiry, collaborative help, and her growing expertise on the Internet. No wonder she was “amped.” Was it magic? Alchemy? We think it was the persistence, response, and revision that come from being more comfortable with writing. As we’ve already observed, we saw Nikki reshape the artifacts themselves: the very thing that shaped her writing thus became the very thing she re-shaped from her own perspective.

IV. The Closing Act: Exercises for Magic in the Classroom

As our portraits of Nikki, Anna, and Clark illustrate, we think that no matter what type of class you’re teaching, or where it’s held, writing about relevant artifacts can enhance any curriculum. But more important, it is a way for learners to reflect on their own perspectives as they learn the content of the course, whatever the discipline. It stretches students’ research, reading, writing, revising, and collaborating skills, not to mention their self-knowledge and identity. We hope you agree. The pages that follow provide examples of exercises we’ve developed for doing just that.

V. The Magic Is Rigor, Response, and Revision

We like to think that the good writing teacher finds the alchemist in each of her students and then, like Murray’s magician, teaches them how to hide the messy processes behind the final draft. And, on the other hand, for those of us who teach writing, there’s much more about that world than we sometimes notice. There are the things we carry, whether they are woodcarvings, stilted ideas about academia, or pepperoni. When we write about an artifact, we don’t lose the object in the writing; we add and create and describe an object until it is a double of itself. When we examine its old meaning, we make new meaning. We like to think that writing enhances the cultural significance of what some would call “reading” artifacts.

Rossina Zamora Liu is Clinical Assistant Professor in the College of Education. She has a PhD from the Language, Literacy, and Culture Program and an MFA from the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa. She is a faculty fellow in the Provost’s Office of Outreach and Engagement, the director of the College of Education Writing Resource, and the founder of the Community Stories Writing Workshop at Shelter House and the local Veterans Affairs where she collaborates with community writers and writers from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Nonfiction Writing Program at Iowa. Her research focuses on public literacy, community and folk practices, equity and access in education, nonfiction writing pedagogy, and narrative construction and identity. She has essays and articles in literary and scholarly publications.

Bonnie Sunstein is Professor of English and Education at the University of Iowa, where she directs the Nonfiction Writing Program. For over twenty years, she has taught essay writing, ethnographic methods, teaching writing, and folklore. She taught for twenty earlier years in New England colleges and public schools and conducts writing and teaching institutes across the U.S. and around the world. Her chapters, articles, and poems appear in professional journals and anthologies. Her FieldWorking: Reading and Writing Research, in its fourth edition, and five other books are popular among teachers and writers. Recipient of many awards and grants, she is working on a book about teaching nonfiction writing for the University of Chicago Press.

Works Cited

Abrahams, Roger. 1992. Singing the Master. New York: Pantheon.

Bauman, Richard. 1984. Verbal Art as Performance. Long Grove: Waveland Press.

_____. 1992. Folklore, Cultural Performances, and Popular Entertainments: A Communications-Centered Handbook. New York: Oxford University Press.

Briggs, Charles. 1988. Competence and Performance: The Creativity of Performance in Mexicano Verbal Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bronner, Simon J. 1986. “Folk Objects,” in Folk Groups and Folk Genres, ed. Elliott Oring. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Ebert, Roger. Review of The Red Violin. http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-red-violin-1999.

Geertz, Clifford. 2003 edition/1977. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, 3-32.

_____. 1988. Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. 2004. The Annotated Brothers Grimm. Translated and edited by Maria Tatar. New York: W. W. Norton, 4.

Halton, Eugene. 2011. “Object Biographies,” in Encyclopedia of Consumer Culture, ed. Dale Southerton. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Hornstein, Gail. 2009. Agnes’s Jacket: A Psychologist’s Search for the Meanings of Madness. New York: Macmillan.

Kouwenhoven, John Atlee. 1964, 1999. “American Studies: Words or Things?,” in Material Culture Studies in America, ed. Thomas J. Schlereth. Lanham: Altamira Press.

Kurin, Richard and C. Wayne Clough. 2013. The Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects. New York: Penguin.

Liu, Rossina Z., ed. Spring. 2012. Of the Folk: Reflections. Iowa City: Times Club Editions at Prairie Lights Books.

Lord, Albert B. 2000. The Singer of Tales, eds. Steven Mitchell and Gary Nagy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

MacGregor, Neil. 2011. A History of the World in 100 Objects. New York: Viking.

Miodownick, Mark and Sarah Hunt Cooke. 2013. Stuff Matters: Exploring the Marvelous Materials that Shape Our Man-Made World. London: Penguin.

Murray, Donald M. 2004. A Writer Teaches Writing. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Noonan, Meg Lukens. 2013. The Coat Route: Craft, Luxury, and Obsession on the Trail of a $50,000 Coat. New York: Scribe.

Object Biographies: The Other Within. Analysing the English Collections in The Pitt Rivers Museum Project, http://england.prm.ox.ac.uk.

O’Brien, Tim. 2009. The Things They Carried. New York: Mariner.

Planet Money Makes a T-Shirt http://www.npr.org/series/248799434/planet-moneys-t-shirt-project https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r2Zod7Sd3rQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYa4zneKbeY.

Prown, J. D. 1982. “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method.” Winterthur Portfolio. 17.1: 1-19, Spring.

Raffel, Dawn and Sean Evers. 2012. The Secret Life of Objects. Los Angeles: Jaded Ibis Press.

Remnick, David. “Going the Distance: On and Off the Road with Barack Obama.” New Yorker. January 27, 2014.

Rivoli, Pietra. 2015. The Travels of a T-Shirt in a Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Market, Power, and Politics of World Trade. Hoboken: Wiley.

Schlereth, Thomas J. 1985. “Material Culture Research and Historical Explanation.” The Public Historian. 7.4: 21-36, Autumn.

Sims, Martha and Martine Stephens. 2005. Living Folklore: An Introduction to the Study of People and Their Traditions. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Sunstein, Bonnie and Amy Shoultz. “Topic Sheets.” The Turabian Teacher Collaborative. http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/turabian/tcc/topic_sheets.html.

Sunstein, Bonnie and Elizabeth Chiseri-Strater. 2012. FieldWorking: Reading and Writing Research, Fourth Edition. New York: Bedford St. Martin’s/Macmillan.

Toelken, Barre. 1996. The Dynamics of Folklore. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Turkle, Sherry, ed. 2007. Evocative Objects: Things We Think With. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Turner, Victor and Richard Schechner. 1988. The Anthropology of Performance. New York: PAJ Books.

Williams, Anna. 2014. “The Story Shall Rise Again: A Southern Pilgrimage.” unpublished paper, University of Iowa.