Photographer Stephen Furze is a Mind-Builders alumnus who documented the historic 2020 protests.

As a child experiencing the flight and fear of neighboring families when, like us, Black veterans with their families moved quietly into promising little neighborhoods in Queens;

Being “woke” by the prejudice exposed when I was a teen applying for my first summer job;

Seeing “Whites Only” signs during summer road trips with Dad to Grandma’s house in North Carolina;

Cheering with my family at the dining room table as we watched Malcolm’s incisive debates with TV newscasters, absorbing the facts he articulated and recognizing the wisdom he preached of creating our own–our own institutions, businesses, and jobs; our own narrative of who we are, have been, and can be; our own understanding and belief in each other; and Malcolm’s evolution to seeing what’s possible beyond racial divides after his Hajj to Mecca, of creating our own megaphone for the truth;

Witnessing Vietnam, the assassinations of John Kennedy and Dr. King, the death and indignities that Black and white civil rights demonstrators staunchly faced, the poignancy of The Last Poets, and that welcome baptism in my first weeks at NYU marching and shouting with comrades in protest…

It was all fertile ground–once again nourishing the growth of strong roots standing in our ancestors’ defiant remains, a history of resilience that provided the needed courage and faith to believe in our ability to create something powerful and life-changing, from a dream that insisted it could be so. Just as that rich earth had nourished the start of Mind-Builders ten years earlier, there came the prospect of creating a vibrant Folk Culture Program with teens learning the value of their neighbors’ and families’ stories, talents, and traditions, of documenting and interpreting their own history.About Mind-Builders Visitors and annual parent surveys overwhelmingly recognize Mind-Builders for its welcoming and supportive family atmosphere as we meet our mission “…to inspire the growth of youth, families and the community through quality arts and education programs.” Since 1978 Mind-Builders has grown to serve over 700 students annually through close to 200 weekly group classes and private lessons in various musical instruments; several forms of dance, theater, visual arts, martial arts, a full-day Pre-Kindergarten class; and our special community Folk Culture Program’s research, documentation, and presentation programming. We create a learning environment for our young people, their families, and our community that is nurturing, challenging, and exciting—one that transforms lives with inspiring instructors; an engaging curriculum; and an appreciation of our heritage, creativity, and unlimited potential. Operating out of our own four-story former municipal building, students age three to adult participate in free or subsidized and affordable classes and community or citywide productions. Energetic audiences in the thousands participate and support students, special themes, and artists each year.

∾∾∾

I was hooked from the first moment I saw Beverly Robinson in 1988: a head taller than the crowds around her, moving with the wide smile of an exquisitely passionate and totally present conductor; translating her special knowledge into everyday language; warm and at one with artists and tradition bearers, community folk, youth, families, and scholars like herself. Beverly was there masterfully curating presentations both inside and outside the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center during the Arts of Black Folk Conference for Community Organizations in the spring of 1988. It was astounding to see how much could be learned inadvertently in the midst of live presentations with commentary, skillful questions, audience participation, and everyday materials referenced on display. Now that’s the way young people need to learn our history and culture–from their family, neighbors, and master artisans all around them, I said to myself as I took in that day. Over time I would see Beverly grab and educate us all, revealing connections between common things like hand-clapping rhymes, doowop, church sermons, shipbuilders, codfish cakes, break dancing, capoeira, and more. She was at least as excited as I was at the prospect of building a thriving community folk culture program in the Northeast Bronx. She made the first of many regular trips from her California home and UCLA enclave, during summer months and breaks, teaching our local teens and simultaneously becoming a mentor for me. After more than ten exciting years of coaching and devotion, of being our program’s scholarly cheerleader all over the world, of being an ever-loyal personal friend of mine and godmother to our sons, a compatriot and transformative bright light, there was no preparing for Beverly’s seemingly sudden passing from pancreatic cancer in 2002. Today, our Mind-Builders Folk Culture Program is named in Beverly’s honor. Now and every year since 1989, interns ages 14 to 21 memorize her definition of folklore, starting in their first workshop, and share it with audiences at the culminating public presentations for school and youth groups, their families, and community: Folklore is the combination of two words–folk, which means people, and lore, which means knowledge. Folklore is a special knowledge of the people that is passed down from generation to generation or that holds groups or communities together. Bev’s culminating public presentations with our students each year were often her extraordinary concept of a “Living Museum,” with students and her as curators, or facilitators. Highly skilled artisans, stories, displays, and interpretive materials could be found in different studios throughout our building. But they could also be found in public libraries or the park down the block, spread across the tables near the swings, by the basketball and handball courts—perhaps with the players enlisted to work, help, or bring friends as an audience. While adaptations have been made as space, time, funding, and genre require, Beverly’s basic course outline, strategies for fieldwork—including interviews and documentation—and her enthusiasm for engaging the public and acknowledging the important work of dedicated tradition bearers, always remain as the goal and as a template for replication.

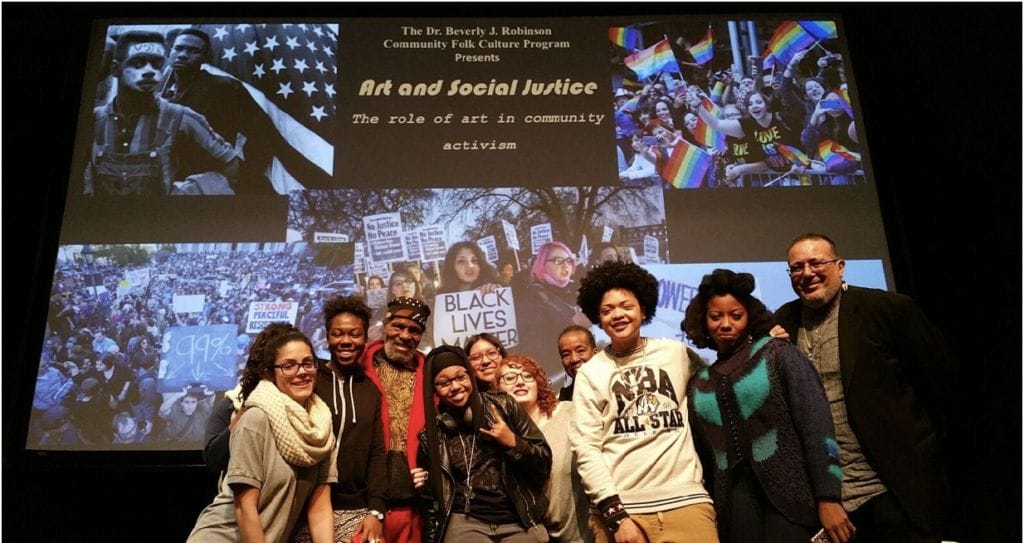

On the Schomburg Stage: Interns and artists at an Arts and Social Justice program, including Abiodun Oyewole of The Last Poets, author Madaha Kinsey-Lamb, painter/muralist Sophia Dawson, spoken word artist/now rapper Nene Ali, and George Zavala, former Program Director.

Mind-Builders Fosters Youth Agency “The Mind-Builders High Five” appears on posters throughout the building and are reinforced through interactive student orientations: Be friendly and kind. Be on time and prepared. Give 100%. Create a safe space. Respect differences. In progress reports teachers summarize students’ sense of belonging, generosity, mastery, independence, and awareness of cultural heritage. Students complete anonymous surveys rating instruction, the facility, and other factors. More formal opportunities for student self-expression, creativity, and professional counseling support have been launched through a new Arts Passage Xpress Program. Former students stay connected. For example, one recently recommended that our student recruitment state that “all genders are welcome.” It is a point well taken and will be included and considered in planning for young adult alum representation on the Board of Directors.It’s not just a cliché when we say that young people are our hope for the future—as long as we accept the responsibility of making sure they have a truthful foundation to build on and opportunities to access knowledge and understanding that may have been missing or different in their social studies class. Our curriculum nourishes their hearts and minds and counters the daily construct that centers whiteness. From that sense of responsibility Mind-Builders Folk Culture Program allows students to explore what may be for many an alternative or expanded view of history. As an example, we share a map of Africa as a continent of 54 countries, with lines delineating routes of ships and numbers for what may have ultimately amounted to close to 10 million African people kidnapped, tortured, and sold as free labor in Europe, Brazil, Cuba, across the United States, the Caribbean, and the Americas. It provides foundational knowledge for small groups to dissect and report back to the class, which sparks investigation into other materials, including audio and video clips, photos, music, films, posters, and news articles. Our curriculum includes many activities for understanding cultures and differences to promote awareness of unconscious bias, stereotyping, and prejudices we humans incline toward. With the rapid switchover to safer online learning following the citywide shutdown, we continue to re-shape and refine the interactive modules, individual home and neighborhood assignments, artmaking, and materials. The core activities—Identify, Document, and Present—taught and practiced throughout the Folk Culture Program’s five weeks in July and August introduce or reinforce interviewing, note taking, photography, and audio and video recording. Students practice these skills by interviewing family and community members. They develop creative presentations to share with peers, family, and community members. During the school year, classroom teachers with school groups attend Folk Culture Program presentations at the Bronx Music Heritage Center, the Schomburg, the National Black Theater, or neighborhood libraries. We send preparatory activities that can be done days prior as starters for class discussions, home assignments, artifact interviews, or other specific lesson plans. Some are available in hard copy or online for free from sources like Mosaic Literary Magazine. It’s beyond my imagining now, what outside-the-box series of interventions, training curricula, and opportunities for developing meaningful relationships with local residents could have possibly resulted in an officer like Derek Chauvin radically shifting the underlying fear and hatred that makes him a threat to life and limb in our communities. Involving community organizations in some phase of the training of police officers and in contributing to the evaluation of an officer’s readiness to serve the community are innovations that have been floated as requirements to consider. Education happens through the stories we tell in our families and communities to stay safe as well. Black families have “The Talk” early on, especially with our sons and grandsons–as well as repeating many frequent, anxious reminders thereafter throughout their youth and young adulthood when they are about to go out. We talk about racism, the police, and what to do or say that might save their lives if they are stopped. This, my fluttering stomach reminds me as I type now, is not what may seem like a calm, matter-of-fact account of our everyday lives—although the words travel so easily across the paper. It’s a lifetime anxiety and nightmare. How many could imagine that recurring “Talk” as a part of their regular lives; or the silent fearful tears I let roll sideways quietly as I laid next to my husband and heard late-night radio years ago declare that Giuliani had been voted in as the Mayor of New York City? Or the practical and psychological machinations required even when embarking on a vacation adventure to anywhere in U.S. or in the world to any area where there are more white folk than Black folk? How do you teach about this? It’s the anguish and heartfelt questions bravely raised and patiently, painfully answered. It’s a thoughtful, unflinching curriculum of “social studies,” folk culture studies, and an honest world and national history developed for all students in the nation. It’s deeper, broader conversations, sometimes tinged with the humor of the sad irony of it all, with friends, board members, corporate partners, co-workers, neighbors, and family at the dinner table. It’s also economic engagement on any level with only those corporations, legislators, media, et al. that are responsive. But who could know by all appearances on any given day that our history and personal experiences have bred these necessary survival mechanisms? Dr. Vincent Harding, a key figure in the Civil Rights Movement, in an interview before his death referred to the U.S. as a “developing nation” in its nascent growth as a fully multiracial, multi-religious, multiethnic democratic society. Ignorance as a factor for some well-meaning folk can’t be ignored either. Recently listening to the podcast Talking to White Kids about Race and Racism on WNYC radio, it was clear that more white parents now see that antiracist education must include potentially uncomfortable and urgent conversations with their children, too. These are conversations that need to happen more than once, age appropriately, and maybe earlier than parents would have imagined hearing these stories in their own lives. Since I’ve seen the miraculous transformation that so many young people undergo as they work through particular stages of their age and development with proper support and their passionate participation in protests, campaigns, and these difficult conversations, I place my bets on them and remain heartened that our young people and those of all ages who are outraged and aching now will hold fast to the light, relinquish the comfort zone, reshape that “curricula” for daily life, and get to know neighbors and co-workers more fully. This can open up this country’s real history.

These vital partnerships support our programs in various ways and may be helpful contacts for research or resources when looking to develop related activities or concepts: Ramapo for Children with Mind-Builders’ annual teacher training and follow-up coaching Good Shepherd Services for counseling support or family referrals and related staff coaching The Will to Adorn/Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage for targeted project support, training, and presentation collaboration, and ongoing consultation Bronx Music Heritage Center as a venue for presentations and a resource for connecting with tradition bearers City Lore’s research resources, project collaborations, and curricular handouts to strengthen interviewing skills CCCADI and the NYPL Schomburg Center’s exhibits and resources for student research Community Works for audience development and outreach to school groups for public presentations EARS peer leadership and mediation training including the 47th Precinct’s Youth Explorers and their police officer escorts Educators for Social Responsibility for curriculum that underpins our key bias awareness and conflict resolution and mediation strategies Literary Freedom Project’s Mosaic magazine and digital lesson plans on Black Lives Matter and other topics of the African Diaspora

∾∾∾

Power, Beauty, and Responsibility in Action The Dr. Beverly J. Robinson Community Folk Culture Program expands our opportunity to continue the evolution of a curriculum that further examines equity through an historical and socio-political lens of the African Diaspora, slavery in the U.S., and strategies of social justice movements. The cornerstone content explores power, concepts of beauty, and responsibility. How would Beverly view my thoughts on these as lessons in power, beauty, and responsibility? I think they are in line with what I learned from her passion for this work. Young people are learning and experiencing the power of our voices, stories, and culture documented and interpreted by ourselves. Within this power are skills and inspiration to pursue advanced and college training and careers; heightened respect for family, others, and our own potential; and the invaluable inspiration that our culture and traditions have had globally for millennia. It is so important to reinforce the power of knowing we all are capable of great things; the potential of each of us is unknown and limitless; the limits we encounter are not a reflection of a lack of effort, intelligence, or worth, but of a system in place since before we and our parents and theirs were born, based on prejudices we humans develop or devise in pursuit of wealth or power, or against those who are different from what is familiar. Beauty and the beholder. Beauty is us. Just as I learned, along with my mother and godmother when Beverly Robinson convinced them to share childhood rhymes and ditties at one of our more intimate public presentations, there is beauty in everyone’s culture, in the stories and humor, the cocky language, the love put into the hand-laced items, and the light in their eyes for what was once a source of shame and evidence of their childhood poverty. This perspective can begin to battle with the persistent internalization of a European-based concept of beauty that we begin taking in as a child, which can be such a killer. On any day, right now, seeing some of our children at play, listening to our family members, friends, or students talk unfiltered to and about each other, can reveal astonishingly demoralizing negative thinking about even the speaker’s own skin color, hair, and facial features to an extent that can be actually painful to hear. My good friend’s daughter Adila Francis recently sent a link to her funny, insightful blog “Love the Skin You’re In” in which she was talking about the prevalent, sad issue of colorism and a preference for lighter skin when she was little. It is also not rare to hear this expressed by grown men and women of color now. In her blog she included a link to a CNN feature on a study some years ago with Anderson Cooper asking a five-year-old African American child to share what she thinks about her skin color. To hear that she “sometimes” thinks her skin looks “nasty” because it’s “dark,” and that she believes grown-ups think so too, is devastating. It’s also motivation to rethink the concepts of what majority traits have been presented to us, our families, and society at large as the absolute standards for what is considered beautiful, when you have had privy to an understanding of colonialism, oppression, the psychology, economics, and politics underpinning the institution of subjugation. There is a sense of responsibility to interpret and document accurately for historical and educational understanding of the arts, artists, and traditions and a responsibility to the family, ancestors, and community who have entrusted us with the treasured stories of their lives and passages; a responsibility to be accepting of the differences we encounter and to become conscious of the roots of our own biases; to pass along what we have learned so that others may understand and see and realize their value and potential; to have the confidence to pursue our gifts without thinking we were born “less than”; the responsibility of understanding the ego fragility that has evolved in all humans and not to misuse that consciousness, but to support and help each other if you have been fortunate enough to have overcome some aspect of this that others have not. The Future Our future curriculum continues to evolve and stay current with how contemporary people and youth are communicating their lives and stories and the development of their traditions, style, vernacular expressions, and art. We’ve refreshed our look at social justice movements and issues and are including how such narratives of related challenges they and their families may have heard, told, or experience matter. We received serious photo documentation of local protests from former Folk Culture Intern Stephen Furze (See section that follows). His work is another exciting, rewarding example to fuel the future growth of the program as alumni reconnect and possibly consult or train advanced students. It also speaks to the impact that former Folk Culture Program Director Jade D. Banks had on her students’ development and the lifelong mentorship position she maintains in many of their lives as they continue in related fields with determination, fine skills, and astute consciousness that her encouraging, captivating approach, infused with their analysis of principles like equity throughout their growth, has sustained their relationships over time. Yet, while hard hearts so slowly evolve and teaching for equity ultimately becomes standard curriculum throughout our nation, how will our children and communities be safe and self-actualize; how will we deal with the many Derek Chauvins? He and others like him must be weeded out and know that the full force of the judicial system will protect its citizens and lock racist murderers away definitively. Ultimately, if you and I and our children, communities, and legislative public servants remain vigilant and diligent, the courts and laws, our institutions, and our neighbors who are stirring themselves awake, will stay “woke” for this life-giving cause; the life, liberty and pursuit that is the goal. I’m actually excited too by the prospect of learning more about the scholars and scholarship presented in a virtual seminar this past June that was produced by the Schomburg Center for the Research of Black Culture in collaboration with Haymarket Publishers, and was entitled “Abolitionist Training and The Schools Our Children Deserve.” I feel a smile start to rise as I conclude by sharing the words of John Wright—a friend whose government relations firm assists organizations that work with underserved communities. In closing a letter he sent out not long ago, John’s words resonated dearly for all of us receiving it: “Please be safe and continue to be healthy, and let’s believe that we can and will be better together.” I had stopped to read those last few words again, this time seeing images of “We the people” down the block and across the globe; carrying signs while wearing masks; retooling our art, our work, our purpose; and being lit again by that relentless faith and determination. We can and will be better together.Madaha Kinsey-Lamb is President and Founder of Mind-Builders Creative Arts Center. She holds an MS in Educational Leadership from CCNY and a BA in Elementary Education from NYU. She is also a poet and writer. URLs https://onbeing.org/programs/isabel-wilkerson-this-history-is-long-this-history-is-deep http://www.mosaicmagazine.org https://www.labrandshe.com/blog