by Nate Grimm

The Personal Value of Interviewing

It wasn’t until I decided to interview my grandparents that I started to understand the power of the interview. Grandpa had told stories before, but not for a formal interview recorded for preservation. I formally interviewed my grandparents right after I graduated from college, asking them about how they met, what their parents were like, Grandpa’s experience as a Seabee in World War II, and their life on the farm after the war. I used that experience to guide my instruction for an oral history assignment with sophomore U.S. history students in my first few years of teaching at the high school in Slinger, Wisconsin. With History Center of Washington County help, we interviewed over 40 veterans of World War II.

After that teaching experience, I felt something was missing from my interview with my grandfather. I needed something more about how Grandpa connected to place, the farm that he lived on his whole life. I returned to talk to him again, this time changing the location from his living room to his pick-up truck. After explaining the goal of writing a family history book to my grandfather to help tell his story to future generations, he gave consent for me to use an audio recorder while he was driving his truck around the farm so that I could capture stories more directly about the farm.

I found that asking him questions while he was in his element, the farm fields, had value. He added stories because he saw an object, building, setting, or sensory cue that triggered memories. He was driving, so he had control over what places he was going to show me, but my questions helped give him ideas and my follow-up questions helped him add detail. I also used this technique with his son, my uncle, who worked on the farm with his father. We went to similar areas of the farm to get a second perspective for the family history book.

This two-pronged interview process helped me understand the life of the farmer and how the farm and family were constructed. It also deepened my bond with my grandparents. After transcribing and storing the video and audio interviews, my grandparents’ voices were preserved in multiple formats long after they were gone. The experience gave me the confidence to treat others whom I’ve interviewed like family members. It also inspired me to continue to teach students about the value of interviewing and immersing interviewees in a location that might facilitate more detailed responses.

Collaborations are key for interviewing projects. After working closely with the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Sociology Department on applied sociology projects, the Wisconsin Teachers of Local Culture with their Bringing It Home folklife education project, and the Wisconsin Humanities Council Working Lives Project, we have begun to take a more thematic approach with history students interviewing people about the past and sociology students interviewing people about the present. We’ve also begun to reach out beyond the social studies curriculum to work with other high school departments and more community members in businesses, government organizations, historical societies, nonprofits, and civic organizations (See also NCSS 2013).

Interviews as a Teaching Strategy

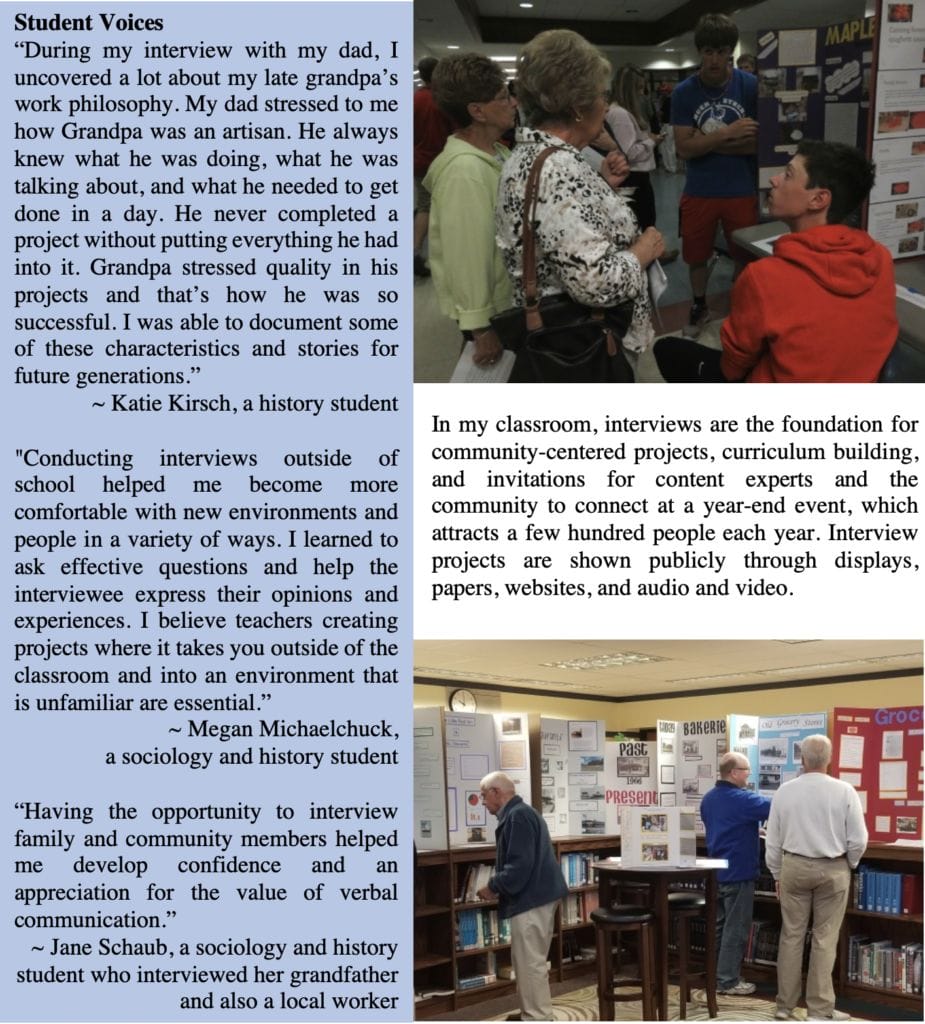

History and sociology students at Slinger have interviewed over 100 people each year during the last 20 years. History students conduct oral history interviews rooted in local history and sociology students conduct interviews rooted in local culture. Students have interviewed adults at school, homes, or workplaces, and in the process I have observed them make a deeper connection with people from other generations, preserve community and family history, and create bonds with others in a society increasingly reliant on fewer face-to-face connections. Interviews also link students with place and deepen understanding of identity formation, shared roots, rituals, norms, values, roles, community development, and cause and effect—aspects of the social sciences that are not always easily learned through other curricula.

Curriculum constructed by students and teachers derived from local interviewees can engage future students and the community. Teaching students tips for conducting and archiving interviews relays communication strengths and weaknesses that will benefit them as citizens and in their careers. Students gain experience in empathy, the value of word choice, preparation and background research, how to stay in the moment, the importance of listening, and how to get to the heart of complex stories. Interviews often help students see the human hands and minds behind workplaces, organizations, communities, technology, and end products. In a world with more expectation of automation, students become aware of human actions and individual choices that lead to continuity and change.

Teacher Preparation for Interviewing, with Examples

Use community members to help identify participants

To prepare for thematic interviewing, during the summer I do some fieldwork and invite people who have ties to the chosen theme to participate. I’ve collaborated with veteran teachers and retired teachers to help build a list of categories and then brainstorm who should be interviewed within each category. Sometimes the teachers even join me when I visit people and places on the list to learn more and prepare for the school year. While students sometimes pick people they know to interview, there are students who want to stretch outside their comfort zone to meet new people—the list comes in handy for those students.

Here is a sample of themes and lists for local history and culture subjects in our area.

Stay observant for good interviewees for specific students

Example 1: When we had a sophomore music artist in my class, I thought about a Slinger alum who was a lead singer in a band. I arranged for her to come to school on a weekend to be interviewed by this student. It was interesting to hear the questions the student artist had for someone who had experience in her career path. That sophomore ended up being on the TV talent show The Voice a few years later. Sometimes part of the success of an interview is just getting the right two people together. Alumni are often very eager to give back to their alma mater, especially when someone is taking an interest in their career field.

Example 2: While sitting in the lobby getting my brakes fixed at a local auto service shop, a man started a conversation about his armed forces experiences on Eniwetok Atoll testing hydrogen bombs as part of Operation Castle. I thought about my ultra-curious science student and asked if he’d like to be interviewed. The student conducted one of the better interviews because he asked questions about the hydrogen bomb that other less scientifically curious students may not have thought to ask. (Listen to an interview excerpt with Richard Schmidt.)

Research interview candidates through fieldwork and practice conducting interviews yourself

There are times when I’ve done short interviews during my summer fieldwork to learn more about a subject, start building a strong interview list, and keep my interview skills fresh. I also learn what areas might be challenging for students in that theme and get to know the people before the students do. Occupational culture has become a consistent component of our yearly themes.

When we were focusing on recreation, I visited the Slinger Super Speedway race track and Little Switzerland Ski Hill to see how they operated, who was there, and what adults were taking the lead. The visits revealed mentors and workers, who were often hidden to students and the public, who helped make businesses and gathering places sustainable.

Calling a local conservation foundation to identify a terrestrial invasive species expert led me to a nature walk with him to observe his technique. I knew by listening to his teaching style that he’d be a good interviewee for students. I heard about a group of villagers who met every week to talk around a potbelly stove in a retired mechanic’s old garage, so we set up a Fox Valley Writer’s Project Summer Camp interview there. The interview centered on what the garage once was and what it is now. Many students were only familiar with today’s service centers. My visit with the retired mechanic led to ideas for school-year interviews with other mechanics, gas station owners, and fuel transport workers.

Retired mechanic interview.

Photo by Robyn Bindrich.

Teaching Students Interviewing

The interview process and product need to be modeled and students must practice creating questions and interviewing. A good way to help students tie content to the curriculum is to share with them sample student interviews. In addition, students see examples of how professionals interview. Oral historian Studs Terkel’s books are helpful for history students (1990; 2011a, 2011b). In sociology, we use University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh sociology professor Paul Van Auken’s Hmong Voices: Fox River Heritage and Perspectives (2014) to show how researchers interviewed Hmong interviewees about how they interact with the Fox River. Van Auken, as well as a local Director of Communication for Cooperative Educational Service Association (CESA), Dean Leisgang, visit yearly to model and give tips to students about interview techniques. Having professionals demonstrate open-ended questions, patience, and empathy has helped teachers and students use similar style and techniques.

Students in both history and sociology practice class interviews when the teacher starts the interview and the students ask follow-ups. I use large group instruction, practice interviews, and conferences to customize questions to interview subjects before they conduct interviews on their own.

Students in both history and sociology practice class interviews when the teacher starts the interview and the students ask follow-ups. I use large group instruction, practice interviews, and conferences to customize questions to interview subjects before they conduct interviews on their own.

Beginning Interviews with the End in Mind

In teaching students interviewing, I start by reminding them to think about where their interview may go. The stories need to be preserved in ways that others can understand them. Some interviews might be preserved for family histories, others might be shared in a community night celebration, while others may only be seen by the instructor. Release forms are used and we teach students archival practices and ways to share with many audiences—their family, the teacher, or the public.

After audio or video recording the interview, I ask students to extract parts for a paper. For written text, students choose one of three options: 1) Write a short biography paragraph and add a transcribed section from the interview. 2) Write a narrative about the whole interview, isolating key categories as body paragraphs and using several direct quotes to share the interviewee’s voice. 3) Create a poem as an introduction to a biography.

I have learned that lessons on the difference between paraphrasing and direct quoting are necessary and models are helpful before students begin the writing process. Students and the teacher will need to identify through editing and transcribing which excerpts may be unique or prove to be pathways to additional interviews or stories.

Classroom Focus: Working Lives

The worker is often at the forefront of many social and cultural changes and eager to discuss trends. Interviewing a worker can help students make connections and some students choose to focus on a cultural study of work after the teacher shares a few frameworks for how other sociologists have studied work. For students focusing on cultural study of work, they are shown examples from Douglas Harper’s Working Knowledge: Skill and Community in a Small Shop (1987) and Douglas Harper and Helene M. Lawson’s Cultural Study of Work (2003). The Wisconsin Humanities Council has excellent examples from the Working Lives Projects. Students create interview questions for the workers by building on sample standard questions such as: 1) Describe your typical work day. 2) Describe your training (role models?). 3) What do you most like about your work? 4) What do you most dislike? 5) What are trends that you’ve noticed since you’ve started? 6) Describe other individuals or groups who help you perform your job well. Photos are often collected with permission of the interviewee.

Students reflect about what they learned when they return. A senior sociology student involved in construction and trades worker interviews shared: “Going behind the scenes to talk to design and construction workers helps us to understand how the community functions and works together to stay functioning. We can see how different businesses come together and collaborate.” Sociology student Joey Neumann after visiting several Keller Construction sites said, “The biggest thing I took away from interviewing construction workers was the teamwork…. When you drive across construction sites, you usually don’t typically put much thought into who is doing what on the site.” The interview helped students put a name and a face to the work being done and understand process rather than just product. They reflected on all the work that goes on behind the scenes to construct a building.

Site Visits

Site visits immerse student interviewers and interviewees in a place where students can often get to the core of the individual’s work or identity. Students may observe the interconnectedness between the interviewees and local and regional groups or organizations. It is ideal for sociology students to see individual actions as well as the larger structural perspective. A senior sociology student reflected on the value of the site visit to Little Switzerland Ski Hill. “From listening to the group sales director, I have learned that it takes a lot of teamwork to coordinate events and just an average night at Little Switz. All the team members work together to set up the hills, the sales, and communication between the workers and guests. Their main objective is to keep guests satisfied and to make sure the hill is running smoothly.”

Click here to see a sociology student’s Working Lives project

Conclusion

Interviewing has been transformative at Slinger High School. It has encouraged students and teachers to use inquiry to learn, collaborate, practice staying in the moment, and actively find people and places that intersect. It has become a bridge to create meaningful relationships with local workers and other community stakeholders. The habitual, consistent pathway for a mutual flow of information about the history and culture of the Slinger area has expanded the connection between students, teachers, workers, and community members. Intergenerational relationships are cultivated. Innovators, patterns, interdependent webs, legacies, human hands, and voices are revealed. School walls become permeable. Visitors are encouraged. People are met where they are. Through the interview experience, students and teachers place themselves in a position to be constructive. They sit on the edge of perception, face to face with another human being, ready to learn and grow.

Nate Grimm has helped facilitate thousands of interviews in his 20 years teaching U.S. history, sociology, and language arts at Slinger High School in Slinger, WI. He earned a BS at University of Wisconsin-La Crosse in secondary education, an MA from Viterbo University in education, and has been a sociology adjunct in the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Sociology Department since 2013. He has been a recipient of a Herb Kohl Teachers Fellowship Award, an Edith B. Heidner Award for local history work from the Washington County Historical Society, and has been published in Wisconsin People and Ideas. He has worked with the Wisconsin Teachers of Local Culture, Wisconsin Humanities Council, Cooperative Educational Services Association 7, local historical societies, local businesses and civic groups, and Slinger area workers, teachers, and students to include interview results at an annual local history and culture community night held at Slinger High School.

Works Cited

Harper, Douglas. 1987. Working Knowledge: Skill and Community in a Small Shop. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Harper, Douglas and Helene M. Lawson. 2003. The Cultural Study of Work. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). 2013. The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History. Silver Spring, MD: NCSS, https://www.socialstudies.org/c3

Terkel, Studs. 1990. Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do. New York: The New Press.

—–. 2011a. Good War: An Oral History of World War Two. New York: The New Press.

—–. 2011b. Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression. New York: The New Press.

Van Auken, Paul M., Shaun Golding, and James R. Brown. 2012. Prompting with Pictures: Determinism and Democracy in Image-Based Planning. Practicing Planner. 10.1, Spring.

Van Auken, Paul. M., Svein, J. Frisvoll, and Susan I. Stewart. 2010. Visualising Community: Using Participant Photo Elicitation for Research and Application. Local Environment. 15.4: 377-88.

Van Auken, Paul M., Elizabeth S. Barron, Chong Xiong, and Carly Persson. 2016. “Like a Second Home”: Conceptualizing Experiences within the Fox River Watershed through a Framework of Emplacement. Water. 8.8: 352. doi:10.3390/w8080352.

URLs

http://beta.wisconsinhumanities.org/programs/current-programs/working-lives

https://dpi.wi.gov/social-studies/standards

https://www.slinger.k12.wi.us/faculty/grimmnat/schmidt clip 2 10-4-09.mp3

https://www.slinger.k12.wi.us/faculty/grimmnat/oralhistory.cfm

http://www.heritageparkway.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Hmong-Voices-Final-Report-11.20.14-1.pdf

https://slingerarearacing.weebly.com

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=175&v=KvCBaROunJ0