Ana, who joined our class at Bailey’s Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences in Northern Virginia last fall, was excited to share her parent interview with her classmates, and we were impressed with her willingness to share. Our instructional focus was teaching how to gain information by interviewing others. The desired outcome was to ensure a culturally responsive classroom that would create a safe place for students to share their thoughts. Ana, a student from Honduras, represents one of the many newcomer students enrolled at our school. Our families come from many countries and bring experiences that enrich and enliven our discussions and our learning. We know when students connect with their parents this bond strengthens their knowledge and creates a climate of mutual understanding and cooperative learning. We realize that our students and their parents have a wealth of knowledge to share. As Ana’s mom said, “Having a conversation with my daughter about my life and my experiences is valuable because it helps me to learn more about what she is learning in school, and it makes me feel like what I say is important.”

As educators we need to create opportunities for our students to get information through various avenues. The folklorist’s techniques of interviewing and listening closely provide purposeful, authentic conversations that allow students to develop further insight and a deeper understanding of their world. One way to build these conversations is to teach students how to research and interview community members, experts in various fields, and even their own family members effectively. This process of collecting information enables students to learn more about a topic of interest while promoting oral language, reading, writing, and listening skills. By building these academic skill sets we create a transference of knowledge that supports academic learning. Once students become more proficient in asking and answering questions, they realize the importance of creating a two-way dialogue that allows them to become more aware of themselves and their family histories as well as of themselves as collaborative, global citizens.

In addition, we want students to recognize and appreciate the cultural values their families embrace and be given a chance to share what they have learned with their classmates. In a recent cultural proficiency staff survey, many teachers at our school said they want more opportunities to relate to our families and understand their cultures better. As one teacher said, “I hope to build strong relationships with families and get to know them on a deeper level.” One way to learn from our families is to bring their voices, stories, and knowledge into the classroom through children sharing information gained from their interviews. We use interviewing skills to integrate content, however, our intent is that students will also begin a journey of self-discovery with their family members. This process will lead to inquiry that eventually will help them recognize the inherent cultural component this type of learning inspires. Creating, strengthening, and valuing the community/home/school connection fosters stronger relationships while developing appreciation, building background knowledge, and empowering families. Interviewing brings family stories and traditions to life and helps to break down and refine cultural barriers inside the classroom walls.

Once the process of interviewing has been established, we can begin to incorporate academic standards. Content areas such as social studies, science, and literacy provide a relevant forum for students to share knowledge gained in a meaningful context. For instance, when learning new science curriculum such as plants, habitats, or weather patterns, students can interview family members and ask questions that will connect to personal experiences about these topics. This in turn leads to authentic conversations, giving students the chance to develop higher level thinking skills such as compare and contrast, synthesis, and evaluation. This experience also leads to richer conversations at home, providing mutual understanding and helping families relate to one another more meaningfully.

Conducting Content-Related Interviews

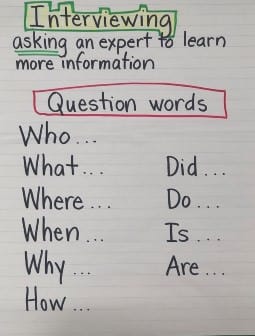

Figure 1. The Interview Process.

Getting Started

Our first step in teaching the art of the interview is to choose a subject area that students will be learning. We intentionally integrate interviewing skills within the science curriculum, because science is relatable, concrete, and provides hands-on learning for students of any age. We begin by reviewing the overarching concepts and state standards of learning to guide decisions on what to teach and to develop pre- and post-assessments. We introduce interviewing by modeling with a non-content related subject related to family folklore such as food or games. We select these familiar topics because children identify with and connect to them in a meaningful context. Next we model the process by having one teacher pose as the interviewer and the other as the interviewee. Then we state the expectations and discuss the definition of the term interview. At this point the students are ready to conduct an interview. Students need to understand that the interviewer’s role is to ask questions and use graphic organizers to record information with words and/or sketches. The role of the interviewee is to answer the questions and describe their experiences. We teach students to use question starters such as who, what, where, when, why, and how to create questions to help them gather information.

Figure 2. Question Words.

We ask students to practice by interviewing each other first. We assign two partners or a small group to work together. The time allotted for this activity depends on variables such as students’ age and stamina levels. We gather students in a circle and ask them to share their interviews. We use guiding questions to aid students in summarizing their experiences such as:

What is something that surprised you?

What is something you know now that you didn’t know before?

How is the game you play similar to or different from the game your friend plays?

Now that students are familiar with the interview process, they are ready to interview a family member. We always start the interview with a topic sentence, for example, “Tell me about a game you played when you were in 2nd grade.” Follow-up questions such as, “Who did you play with? Where did you play? How did you play,” need to be asked to elicit further conversations, which will help students more clearly visualize and understand the topic. During the conversation, the interviewer writes keywords and creates quick sketches. Once the interview is complete, students close by thanking the interviewee for their time. The interviewer brings the completed interview to class and is prepared to share what he or she has learned with their classmates. We give students sentence frames to show their understanding and summarize their findings, for instance: One thing I learned about __________ is__________.

Links to Graphic Organizers:

Interviews about Games (Spanish and English versions)

Interviews about Food (English version)

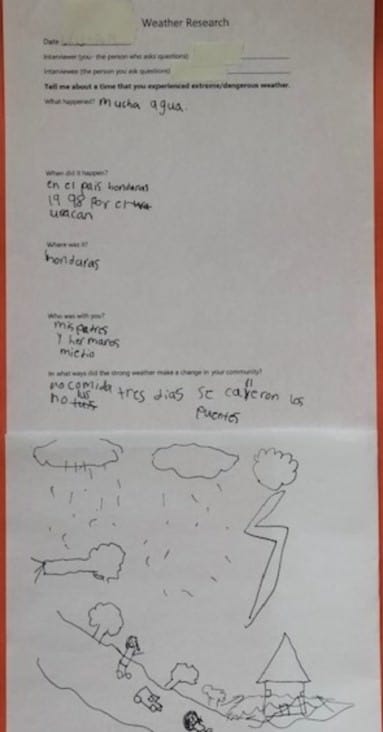

Students are more adept at preparing for and conducting content-related interviews because they have experience brainstorming and formulating questions, developing graphic organizers, and sharing their knowledge. These strategies allow them to interview their parents or experts in various fields of study. This type of thinking and sharing of information also helps to deepen comprehension and show their learning. We design and use pre-, ongoing, and post-assessments to inform our instruction and assess student learning. Figure 3 is a completed weather interview Ana conducted with her mother, while a post-assessment we used for our science unit can be found in the Classroom Connections appendix to this article.

Our students are now able to formulate their own questions on any topic to get more information and develop their research skills further. They are motivated to listen and share because they can connect the information being presented to their lives. We see this process as a cross-curricular methodology. It can be used across content areas and grade levels and sets the foundation for inquiry-based learning. The active engagement of interviewing and sharing also creates cooperative learning structures, creating the potential for students to be passionate, lifelong learners.

Figure 3. Parent Weather Interview Form Filled Out. (Blank Worksheet in Classroom Connections)

Real-World Applications

The assimilation of knowledge gained from students’ interviews can be showcased in many ways. Our final outcome is to create an opportunity for students to display their work through a culminating, lasting artistic expression to be shared and celebrated. We have found that by providing a platform for our students to engage with their families, they create a product that reflects a meaningful and personal viewpoint. This helps to deepen their comprehension of the subject area being studied. Interviews give students and their families a way to share and express what is important to them. Interviewing becomes a creative expression and allows parents to be partners in the educational system. The artfulness of the interview comes through modeling, practice, deep listening, and re-presentation, a process that promotes the need to connect with, understand, learn, and relate to one another.

Find Classroom worksheets and Graphic organizers here:

Classroom Connection: Quick Reference Guide on how to include the Art of the Interview in your classroom.

Classroom Connection: Weather Science Unit Examples and Worksheets

Classroom Connection: Graphic Organizer for Interviews on Play (English Version)

Classroom Connection: Graphic Organizer for Interviews on Play (Spanish Version)

Classroom Connection: Graphic Organizer for Interviews on Food

(Download Connections PDF)

Allyn Kurin is a nationally board certified ESOL teacher with over 20 years of experience.

Gina Elliott has served as the Lead ESOL teacher at Bailey’s Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences for the past 11 years and conducts parent workshops for the school community. Together they have presented numerous programs that strengthen family engagement with a focus on developing home/school partnerships.

Bailey’s Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences is a magnet school in Bailey’s Crossroads, Virginia, just outside Washington, DC. It is one of the most culturally diverse schools in the region with over 700 students in grades K-2. Our students represent over 20 countries of origin and speak more than 30 different languages and dialects.

Recommended Texts

Bowman, Paddy B. 2004. “Oh, that’s just folklore”: Valuing the Ordinary as an Extraordinary Teaching. Language Arts. 81.5: 385-95.

Diaz, Junot. 2018. Islandborn. New York: Penguin.

Elliott, Gina, Allyn Kurin, and Carmela Ormando. n.d. Cloth Stories Lesson Plan: Stories of Perseverance. Art and Remembrance, https://artandremembrance.org.

Fairfax County Public Schools. 2019. Elementary Curriculum Framework: Pacing and Sequencing of Content, https://www.fcps.edu/academicselementary-school-academics-k-6/second-grade

Henderson, Anne T., Karen L Mapp, Vivian R. Johnson, and Don Davies. 2007. Connecting Families’ Cultures to What Students Are Learning. Beyond the Bake Sale: The Essential Guide to Family-School Partnerships. New York: The New Press, 120.

Johnson Martinez, Moly. 2009. Los Hilos de la Vida, Threads of Life: A Collection of Quilts and Stories by Anderson Valley Artists. Boonville, CA: Hilosquilts.

Koetsch, Peg. 1994. Student Curators: Becoming Lifelong Learners. Educational Leadership. 51.5: 54-7.

Locker, Thomas. 1995. Sky Tree. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

—–. 1997. Water Dance. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Moll, Luis C., Cathy Armanti, Deborah Neff, and Norma Gonzalez. 1992. Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms. Theory into Practice. 31.2: 132-44.

Pryor, Anne and Nancy B. Blake. 2007. Quilting Circles-Learning Communities: Arts, Community and Curriculum Guide Grades K-12. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Teaching Tolerance. 1991-2019. Window or Mirror, https://www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/teaching-strategies/close-and-critical-reading/window-or-mirror.