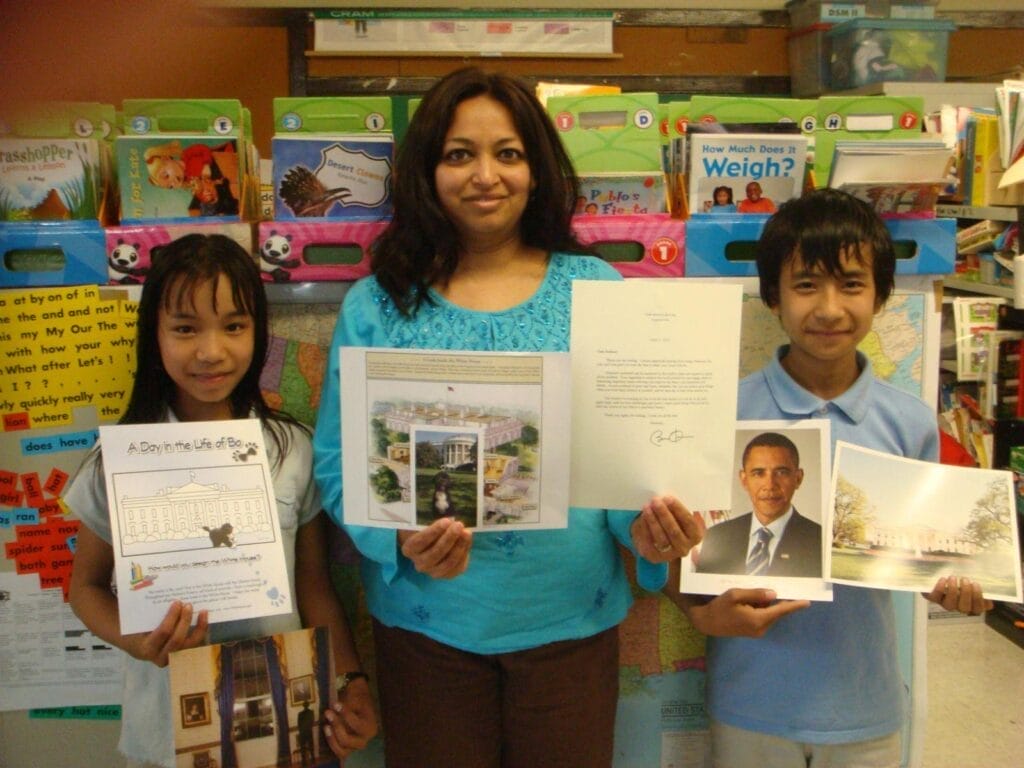

About the photo: Natasha Agrawal (center) and Tzuyi Mah Bae (left) showing the correspondence they received back from the White House.

JFE Guest Editor Michelle Banks (MB) facilitated this conversation between a teacher and her former student, both of whom came to the United States from other countries.

Teachers are often on the frontline of creating spaces for migrant and refugee children to find community and construct a sense of place. Tzuyi Meh Bae (TMB) arrived in New Jersey in 2009 from one of the refugee camps in Thailand where thousands of Karenni people who were pushed out of Myanmar were living. There she met her first teacher in the U.S., Natasha Agrawal (NA) who was born in India. In this conversation, recorded and edited for length and clarity, they discuss and reflect on the time they spent working together.

MB: Let’s start with introductions.

TMB: My name is Bae and I am 24 years old. I came to the U.S. when I was ten years old in 2009. We [my family] were Karenni refugees from Myanmar, but I was born in Thailand, in a refugee camp. Right now, I am living in Indiana and my family is in Minnesota. I just got done with my nursing program at Ivy Tech, so now I’m studying for my NCLEX [nursing licensure exam].

NA: I am Natasha Agrawal, I am a teacher in New Jersey. I have been teaching at Robbins Elementary in Trenton for almost 16 years. Bae Meh was one of my first students. I remember you so clearly, because I think my interaction with you was so intense. And the background that you brought with you and the tons of knowledge you brought with you were just so amazing for me, that a child had experienced the kind of things that you talked about. As a teacher, I didn’t know where to start. You were one of those kids who had seen so much and who had been through so many hardships already, that I just wanted to connect with you. And in my motherly teacher heart, I just wanted to give you the best thing ever and have you heal from whatever traumatic experiences you had gone through, your whole family.

MB: Why did you choose your respective professions?

TMB: I was born in a refugee camp in Thailand, and we didn’t have any hospitals. It’s like, you don’t go to the hospital until you’re dying—so, if you’re sick and you can still move, you just kind of sleep it off. My family, my mom, my grandma, they would get sick, but they never go to the hospital. As a little girl, I wanted to do something for my grandma, for my mom, but there was nothing to do for them. When I came here, I wanted to be somebody that can help somebody when they’re sick. I wanted to be able to do something because as a kid, I felt so useless. That’s why I wanted to be a nurse.

NA: I grew up in India and I went through the Indian education system. When I came here, my own kids were young, and they went to school. The kind of things they would tell me and the kind of relationships they had with their teachers—I was very surprised and wanted to explore this education system. I also felt like while my kids are young, this is the time I can be a teacher and I can still be with them when they’re home from school and have summers with them. But once I became a teacher, I found it to be such an intense experience. Teaching is actually learning; you’re learning from your students all the time. That for me is a constant challenge and I enjoy that a lot.

When I met students like Bae Meh, I felt like if I can even give them a little something that helps them heal or teaches them something, gives them a little more confidence in their own identity, then my job is done. I think that’s very important for me.

MB: What are some of your memories of working together?

TMB: Mrs. A and Mrs. Fitts were my first teachers. I would have them one at a time. I would be pulled for ESL class to go learn English. I think that was my favorite time of the day because I felt like I wasn’t judged. In the classroom, I couldn’t speak in English so I felt so out of place. I couldn’t understand anybody, and there wasn’t anybody next to me talking to me because everybody was just doing their own thing. In ESL class, there were other students speaking the same language as me. I was talking and I was hearing what they’re saying to me.

NA: When you came, you joined with your younger sister, who was I think about seven at that time. And they just about knew how to write their names. I think you had learned a little bit of English though, right? You did know some things.

TMB: Before I came to America? I just learned ABC, but that was about it. I didn’t know how to write my name yet.

NA: Oh, you didn’t. Ok. One of my first memories is you are just writing your name. But you learned so quickly. By the time you left me in two years, you were writing me long letters—really good grammar and everything. So, it’s shocking how much you absorbed, because writing is very hard. You pick up the language first, and you’re listening a lot, you’re speaking.

TBM: I remember writing a letter to the President of the U.S.

NA: Yes, we got a response three times. I still have all of Obama’s letters. (Laughs).

MB: What were some of the challenges you faced in your work as a teacher?

NA: The first challenge was that we didn’t even know where these children had come from. On the registration, it just said Thailand. So, I thought they were Thai, and I’m trying to look up Thai words and how to say hello. That’s not who they were. I was with one of the other kids reading a book about coming to America and how different people come and the reasons they come. One page talked about refugees and this little boy said, “Refugee, refugee, I refugee,” and I was like, “Oh, you guys are refugees.” I didn’t know. None of us understood that because we only knew about the Guatemalan students or the other Central American students. For me, it was a whole new world. I was like, “Oh, what is life like for them now?” As I dug deeper, I found articles, I found the word Karen. We didn’t know what Karen meant. “Oh, these children are Karenni.” I remember one of the kids, Hsar Reh, coming to the classroom and I had a big world map with country flags on it. He stood there for the longest time looking for a Karenni flag. And he kept saying, “Karenni, Karenni.” I didn’t know what flag he was looking for. Then he started to draw it. I Googled it and found what that was. Karenni is a minority.

Not having background enough to reach the children was a challenge because I like to know where my kids have come from. What have they experienced? Who are they? What’s their context? That was something we had to figure out. Also not having any language resources was hard. When they said Karen or Karenni it’s like, “Okay, how do you say hello?” What beliefs are they coming with? For Spanish or for Guatemalan, we have so much available, so that’s easier to figure out. Additionally, they came from a very tropical climate, unprepared for winter. I used to see their moms coming in flip-flops, to drop the kids off. It would just break my heart. They don’t have jackets or coats or something to keep them warm. There were lots of gaps in our knowledge of how to reach them.

MB: What kind of support, if any, did the school have for parents and families?

TMB: As soon as I learned English, we had to be the one translating all the government documents. I’ve always remembered me and my sister trying to read and translating to my parents, but we didn’t know how important these documents were. We had bags of mail because we didn’t know if it was important or not. Our parents could rely on us because we knew some English.

NA: Much later we started a parent class. I did find a Burmese translator who was very willing to come and help out, but Karenni is a minority language, so they didn’t know Karenni, they knew Burmese.

MB: Mrs. A, you talked about learning from your students. Can you say a little bit more about that? What does that mean?

NA: Well, resilience. Things that they’ve been through and things that they’ve shared. I would come home thinking, “Wow, this family has been through so much and is surviving and has come here for a new life.” If they’re going to walk into my classroom, I need to give them whatever I can, as much confidence building as I can do before they leave me and go off to middle school. I had those two very precious years with you. And it was a joy.

MB: Bae, have you ever heard a teacher say that they learned from their students? What are your thoughts on that?

TMB: No, this is the first time I’m hearing it from Mrs. A. I haven’t heard any of my teachers coming up to me say, “I learned a lot from my students.” I feel like you gave me more than I can ever give you. I’m always forever going to be grateful to you because you provided me the foundation that I needed when I first came here. She was the link between my culture and this new culture that I was introduced to when I first came here. I feel if I didn’t have you, I wouldn’t know how to even begin because everything was foreign to me.

NA: That’s what I felt when these children came. They were my kids who needed guidance, who already had the strength, confidence, and everything. They just needed a bit of guidance. That’s all. Everything else was already there. I just wanted to hold them all and say, “Okay, I’m going to just take care of you until you can take care of yourself.”

MB: How did you manage to stay in touch with each other?

TMB: First of all, I just want to say, I don’t remember all my teachers. The reason I remember you, Mrs. A, was because you had a special place in my heart when I was thrown into this land. I was struggling back then, and you were there for me, so that’s why I remember you even after 14 years. I don’t remember who my teacher was from last semester. I always wanted to be in touch with you, but when I left I didn’t have a cell phone. I got to know one of my classmates and asked “Hey, do you know Mrs. A? Do you still have a contact? Give me her email. I want to say thank you.”

NA: I remember the email. I think at one point you emailed me your report card. You were in Denver, weren’t you?

TMB: Yeah, I was in Denver.

NA: And then we met. I came to Denver for a conference. I’m staying at this hotel and I invited you and your sister for a meal. I thought, I’ll take them to the restaurant at the hotel, it’ll be fun and we’ll catch up. And you and you sister came with bags of food. (Laughs)

TMB: Yeah, we hadn’t seen you in a long time. We were excited. We were like, “Yeah, we’re going to feed Mrs. A! This time it’s our turn.” (Laughs)

NA: That must have been almost ten years ago, you were in high school then, right?

TMB: Yeah, I was in high school.

NA: So that was quite coincidental that where they were staying at that time was very close to my hotel. That was wonderful.

MB: What keeps you going, Mrs. A? What are some things that you have to do to be able to continue in this work?

NA: It’s very heartwarming when they post something beautiful, something fun that’s happening in their lives. Or when I read the English that they write—beautiful, well put together sentences. I teach a graduate class and sometimes they come as guest speakers to talk about their experiences. But I think the most important thing, both for me and for the children, is just to be there, just to be a presence in their lives, just like they are in my life. And to cultivate that relationship we don’t really need a lot of books or computers or anything because cultivating relationships is an intangible thing. We just need to be able to be there, to listen, to communicate, and really as a teacher for me to read body language: What does a child need at this time?

MB: Bae, what is the most important lesson you think you learned in this classroom?

TMB: Mrs. A was like the second mother guiding me in the school outside of my family. I learned that I could learn something with the support of others. I don’t need to know everything in the beginning. Even if I started from the bottom, even though I have nothing in the beginning, I can learn things because of the good people around me.

MB: You realized you didn’t have to do it by yourself.

TMB: Right. I have support outside of my family. And just the fact that we went to ESL classes every day, that’s how I improved my English. Spending time with my teachers and the other Karenni kids, I felt I was a part of something.

MB: Is there anything you’d like to say to each other?

NA: You’re gonna make me cry.

TMB: I just want to say thank you so much for everything. I really mean it when I say you were like my second mother. I had my little sister, but I was supposed to be her guide. So, I’m really grateful for you. Even if it’s 30 years or 40 years I’m still going to talk about you. I’m still going to remember all the things you’ve done for me.

NA: I want to say thank you to you because you brightened up my life. You made my life so meaningful when you all came. I was like, oh, I’m useful now. I was just looking at this letter that you wrote to President Obama, “I want to help people that are sick. I want to be a doctor or a nurse.” Things that you projected so many years ago you made happen. You can see how smart you are and what an amazing student you were.

TMB: Thank you for not giving up on us. Thank you for having patience with me. Like everything I have accomplished in life. I feel like it’s all thanks to you because that’s where I built my foundation. That’s where I was able to grow some wings and now I’m flying.

NA: Actually, that’s what I should say to Bae Meh. You make it worth it. We see you all very little and then we don’t see you after that. We don’t know what’s happened and how you’ve grown your wings but to meet you and see you. You’re talking so beautifully. I remember you would just always have your eyes up and down. You taught me how to hula-hoop. I will never forget that. During the summer program we used to be outside a lot in the playground. “Hey, Mrs. A, this is how you do it.”

TMB: I could do that for hours.

NA: See. I remember everything about you because you’re just one of those shining star students that you just don’t forget. Thank you for being who you are and how you push yourself. You’re going to do amazing things with your life, and I want to read all about it one day.