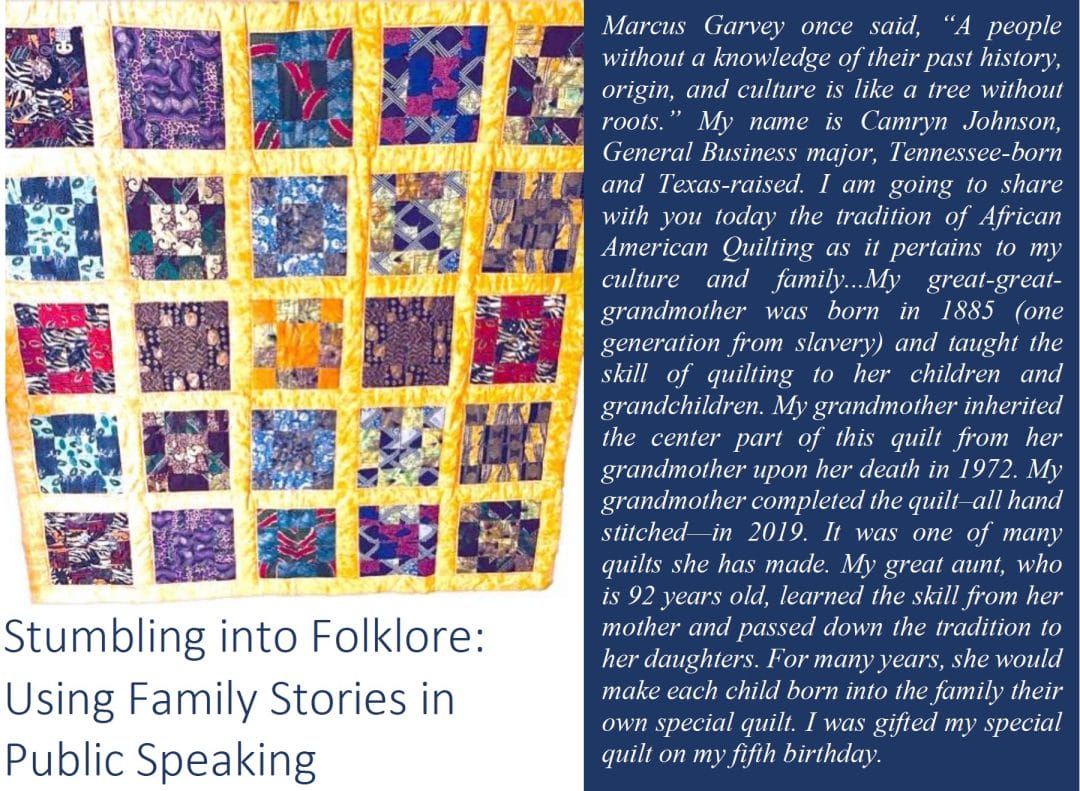

Quilt image courtesy of Camryn Johnson.

Featuring student work and reflections from Camryn Johnson, Haley Priest, Kennedy Johnson, Paxton Ballard, Madelyn LeDoux, Sierra Fox, and Anna Grace Franques

Undergraduates in our Introduction to Public Speaking course share special objects and tell stories from their family folklore, such as in the above excerpt. We teach in the Communication Studies Department at Louisiana State University (LSU). Like many Public Speaking classes around the country, the course requires a formal speech of introduction. As the basic course director in the department, McDonald crafted an assignment for instructors that draws on culturally relevant pedagogy, a pedagogy that concerns itself with student development of “academic success, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness” (Ladson-Billings 2014, 75). Hatchett, currently a PhD student worker in the department, used this assignment in her classes. The assignment has two parts: a warm-up speech called the Family Story Speech, in which students tell a family story, and an introductory speech called the Family Objects Speech, in which students share one or two family traditions using two objects that represent those traditions. Our training and research have not been in Folklore, yet we stumbled into aspects of the field when we asked students to share their family stories and traditions in this assignment.

The American Folklore Society (n.d.) defines folklore as “the traditional art, literature, knowledge, and practice that is disseminated largely through oral communication and behavioral example.” Communication Studies’ various definitions of culture are similar; both fields are interested in how groups develop and perform personal identity through shared behaviors, beliefs, and traditions. Folklore emerges in inherited language patterns and lexicons, as well as in the customs, rituals, and traditions of students’ speeches. In this article, we discuss the ways our incorporation of folklore deeply enriched the introductory speech unit of our Public Speaking course, improving the quality of student work, increasing engagement with course content, and enhancing students’ cultural competence. We want to describe the user-friendly, highly adaptable assignment, share some of our struggles and successes, and offer some takeaways for educators.

The Family Story/Objects assignments respond to Gloria Ladson-Billings’ (1995) call to resist deficit approaches to education by honoring a multiplicity of family backgrounds and linguistic norms in the classroom. Building on Ladson-Billings’ touchstone work, Django Paris (2012) proposes a culturally sustaining pedagogy that “seeks to perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” (95). LSU is a predominantly white institution in which white, middle-class norms tend to dominate the cultural landscape in classrooms like Public Speaking—a discipline enmeshed in a long history of race and class hierarchies and exclusions (Conquergood 2000). Our assignment centers family folklore by inviting students to speak as experts of their own cultural experiences in their unique accents or dialects. The assignment aims to make space for non-dominant voices and to challenge the sense of cultural homogeneity within academic spaces and within the Communication Studies discipline. The plurality of family backgrounds drawn out by calling upon folklore provides a firm foundation from which to build cultural awareness and sociopolitical consciousness. As Paris (2012) writes of culturally sustaining pedagogy, “Such richness includes all of the languages, literacies, and cultural ways of being that our students and communities embody—both those marginalized and dominant” (96).

When we introduce the assignment, we name our positionalities (McDonald—a white, middle-class woman from the South, and Hatchett—an African American, middle-class woman from the Northeast) to encourage students to begin to identify their unique standpoints. Between us, we have used the Family Story/Objects speech assignments with about 250 students over the last two years, both in person and online. In online learning modes, some classes submitted speech videos asynchronously, and others performed speeches synchronously on Zoom. We received written permission from several students to include their work and reflections for this article. Versions of these oral assignments would function well as pre-writing for personal essays or poems, a tool for sketching out a theatrical monologue or narrative performance, an icebreaker to introduce themes of cultural identity and plurality, or an oral presentation as described here.

The Family Story Warm-Up Speech

We begin with a low-stakes “warm-up speech” asking students simply to tell a short family story. We encourage them to think of a particularly memorable family experience or a favorite story that is told and re-told during family gatherings. We note that “family” does not have to be immediate or biological; we define family broadly as “the community who raised you, whoever they happen to be.” The options for family stories are limitless; the stories may be funny, serious, exciting, anything that says a little something about who their families are. These brief speeches do not require any research, and we encourage students to tell the story as they would over a dinner table, bringing their “home language” into the story (Baker 2002).

We instruct students to bookend their warm-up speeches by using “I come from _________ people” for the first and last lines, filling in the blank with an adjective or phrase that characterizes their family. Some examples we heard were “weird,” “bayou,” “country,” “woke,” “card-playing,” and “have your back no matter what” people. The idea to use this line came from our LSU colleague Emily Graves (2015), who borrowed the idea from a workshop with performance artist Tim Miller.

Before the warm-up speech, we lay the conceptual groundwork for the assignment, underlining the significance of voice, narrative, and positionality in public speech. We emphasize voice as an aspect of family culture in classroom discussion. We have students read and/or use terms from Judith Baker’s (2002) article “Trilingualism,” which suggests there are at least three different forms of English that Americans need at this time in history: “home” (personal dialect), “formal” (academic/school), and “professional” (specific to one’s career) (51-52). We also have students watch Jamila Lyiscott’s (2014) spoken-word poem, “3 Ways to Speak English,” which considers code switching. We then facilitate a class discussion about what is “proper” speech, who defines “proper” speech, and who benefits from this idea. We encourage students to use their home language if they wish and to feel no pressure to perform a formal voice or code switch. We want to make it clear that voice is part of family folklore and personal identity and that all voices are welcome.

We assert that personal narrative (and the use of narrative generally) is a skill worth practicing for speech composition. We want students to distinguish between an explanation and a narrative. Students may briefly characterize their family in this speech but should spend most of the time telling a story that is dear to their families. We remind them that something should happen in the story. The story can be funny, serious, exciting, etc., but it should have a beginning, middle, and end. To model, McDonald shares a story from her family lore in which a great uncle cuts off his brother’s finger with an axe on a dare-gone-wrong.

We dedicate class time to discussing the relevance of identity to public speaking as a practice. We want students to think broadly about what social norms and cultural groups have influenced their personalities and opinions. An early chapter in our course textbook introduces a dictionary definition of culture: “the distinctive ideas, customs, social behavior, products, or way of life of a particular nation, society, people, or period” (Valenzano 2020). We try to complicate our shared definition of family culture in class discussion by asking questions, constructing alternative definitions, and offering personal examples. Folklore provides a useful framework for thinking about our cultural practices: What do we do, know, make, believe, and say? If “culture” is what we do, how do we perform ourselves on a daily basis? What social practices and meanings have we inherited?

Below are excerpts from our students’ speeches.

“I come from a huge family”

Just on my dad’s side of the family, I have 18 cousins, bunch of aunts and uncles, and a lot of friends we also consider family. Every year during Christmastime… around 11 o’clock, we always go to my grandma’s house, all of us. She lives in this little, tiny house and it’s about like 35 of us all packed in there, and our grandma makes sure to get all of us five presents. But the thing is, she has to open them up with us. So, one by one she opens up five presents with every single person, and as you can tell doing that with like around 35 people, it can take some time. It’s funny ’cause it’s always a question of who’s gonna get frustrated first, who’s gonna yell at her to hurry it up, because it just takes hours and it goes way into the night opening presents. But this year with Corona, we weren’t able to have it for the first time, and she wasn’t able to go to Christmas. And everybody was bitin’ their tongue, and everybody realized how grateful we are to have a grandma that wants to open up all the presents with us. –Paxton

“I come from Catholic people”

It was Easter Sunday, and every family received a candle to light. I was about seven years old, and it was my first year to be allowed to hold the candle, so I was very excited! I lit the candle and brought it back to where my family was sitting. Then the priest said, “You may be seated,” so naturally everyone sat down, but there was a book in my spot. So, as I went to move it, the woman in front of me sat down and her hair went directly into my candle. It immediately erupted into flames and my entire family was in shock. My mom started to pat her head desperately, and I was blowing on it—which in hindsight was probably making it worse. My dad and two brothers were just sitting there and staring in utter disbelief—as was the rest of the church. Then the woman ran to the bathroom followed by my mom and they put the fire out. To this day I will never hold a candle in church again. Now I hope you have learned a little bit about me and my family! We may light people’s hair on fire, but don’t let that scare you off, because we are a proud, Catholic, perfectly dysfunctional family. –Haley

“I come from a relaxed family”

Since it’s Mardi Gras season, I’ve decided to tell a Mardi Gras story. My aunt was in a parade. She was in Zulu. So, she wanted me, my mom, and my grandma to come. We made signs; we made a bunch of stuff, so she’d be able to see us. So, we get out there for Zulu. People are, you know, drinking, playing music, just having a good time like people do at parades. And so, we’re sitting and we’re waiting for my aunt’s float to come up, and eventually her float comes up. She looks us in our face and it takes her a while to recognize us. So Zulu, obviously, is famous for their coconuts—anybody who goes to Zulu knows exactly how people act for coconuts. They will lose their mind over coconuts that they just keep in their house, or maybe in storage. So, she’s trying to hand us our coconuts and beads and everything and people are actively jumping on our backs. So eventually we just decide to give up. Most people maybe woulda lost their minds, but we decided to be the bigger people and just let it go. So, I feel like that’s how I come from a relaxed family.

–Kennedy

The Family Objects Introductory Speech

Once students demonstrate a measure of comfort with telling a family story, we offer some basic public speaking conventions and strategies to transform their original stories into a more involved introductory speech. Speakers select two objects that represent their family’s traditions and compose a three- to four-minute speech showcasing those objects. Students show each object, explain how it fits into the tradition they are discussing, and include at least one narrative or memory of the object in use. Students may include the story they told in the warm-up speech or choose new stories altogether. Our guiding questions for students are, “What is the difference between telling a story and giving a speech?” and “How are you naming or characterizing your family traditions?” To help answer these questions, we use a common rubric for the course that measures five key elements: central message, language, organization, delivery, and support.

Central Message

The central message of any speech should be easily identifiable and memorable. For the Family Objects Speech, the central message should introduce one’s family by sharing personal or family traditions that represent one’s cultural group. The objects should serve as evidence for their personal and/or family traditions and symbolize two aspects of the same tradition or two different traditions. For example, a student speaking about her Cajun culture may display an object that symbolizes particular food practices, as well as a relationship to Mardi Gras festivities. Another speech might address two different traditions–a student might show one object to illustrate how his family celebrates Christmas and another to demonstrate how his family is obsessed with football. In both cases, the central message contains one’s most important family traditions.

Organization

In the warm-up assignment, we want students to practice delivering a narrative; in the longer introductory assignment, we want them to practice composing and delivering strong organizational language that helps to frame narrative examples for the audience. To this end, we ask that speeches include a straightforward statement of purpose (a line overtly naming the purpose of the speech) combined with a preview statement (a line or phrase that outlines the main areas of the speech) in the opening of the speech. For example, one student said, “I’m going to introduce my family by using two objects: this confirmation dress, which represents my Catholic upbringing, and this jambalaya paddle, which represents my family’s Cajun culture and cooking.” As in this example, each object should symbolize some aspect of their family identity, paving the way for each main point to (a) characterize their family culture and (b) illustrate that culture with a story. One purpose of the objects is to practice “chunking” ideas into separate main points to build a speech. The two objects cue the two main points and serve as a structure for composing (and remembering) clear transitions and topic sentences for each main point in this and following speeches in the course. For example, when the student moves to the second point of the speech, she might say, “Now I want to show you this jambalaya paddle–it represents how important traditional cooking is to my Cajun family.” The objects help students to practice fundamental speech composition skills: previewing the speech, transitioning, and naming their main points.

Language

For this component of the rubric, we ask students to put some thought into crafting memorable opening and closing lines. They may continue to use the “I come from _________ people” line to open this speech or compose original opening and closing lines. We offer some techniques for these lines, such as a joke, a surprising anecdote, an antithesis, a metaphor, a rhyme, a quotation, or a “takeaway.”

Support

In later speeches in the course, support takes the form of research. For this speech, however, support amounts to the inclusion of at least one narrative example. In addition to explaining what happens at a family’s Hanukkah celebration, for example, the student should include a brief narrative illustrating a moment in time during the celebration.

Delivery

While we teach many delivery techniques later in the course, for this first speech our main goal is to conquer anxiety and have a good experience “on stage.” We ask students to try to project their voice, to sound conversational, and to aim for strong eye contact with the audience, but we are not too picky about delivery. We urge students to try to enjoy telling a familiar story.

To wrap up the assignment, we employ a short reflection that includes the following:

• How did your speech go? What worked for you or didn’t work as well in terms of your process and/or performance?

• Whose work stood out to you as especially compelling? Why?

• What did you learn about your own culture and/or other cultures?

• What did you learn about speech writing and speech delivery?

Their reflections indicated a strong preference for speeches with “good stories.” Speeches that stood out were ones like Haley’s in which the narrative arc was especially apparent. They noted surprise at the variety of cultural traditions represented in the class. They were proud when the audience reacted to their stories, and many commented on the importance and difficulty of being relaxed enough to “be yourself” as a speaker.

Reflections and Challenges

We want to share some observations about what worked for us, some speculations about why it worked, and a challenge we faced. In our reflections as teachers of these assignments, we found it constructive to understand the task we asked of students as folklore. We think it will benefit students to include the definitions of folklore from the American Folklore Society and other folklore texts in future versions of the assignments to clarify the aims and to assert the art of storytelling as a fundamental communication form.

We consistently found the warm-up speech created a welcoming space for students to showcase their family culture through folklore. In this assignment, many students named their family traditions as part of a specific racial, ethnic, religious, or regional identity (e.g., African American, Asian American, Cajun, Catholic, Southern). Others told funny or shocking stories about family traditions, and their speeches described their families as “quirky,” “competitive,” and “silly.” Overall, we believe that the invitation to talk about “lore” and “traditions” helped students to name and claim their cultural heritage. We want to prioritize this goal in future classes.

For the warm-up speech, the sense of “anything goes” was important for student confidence in what was for many their first attempt at public speaking. In our classes, the Family Story Speech is worth ten points out of a possible eight hundred, while the Family Objects speech is one hundred points. Since the warm-up is a lower-stakes assignment, we speculate that students may feel less pressure to be “perfect” and thus more willing to showcase their unique personalities, accents, and dialects. Both speeches allow students to focus on a topic in which they are experts: their own family. In this way, the assignment upholds culturally sustaining pedagogy by valuing the cultural practices and linguistic competencies of students from all communities (Paris 2012, 95). We saw this notion echoed in many student reflections on the assignment and include a few here.

I have always loved storytelling, especially about my family, so telling one of the many family stories I have was a relatively easy process because the emotion and comedy, which often must be well thought out in order to make a good speech, was already so accessible and easily packed together because it was a real-life memory. –Paxton

At LSU I do not really talk about “family culture.” In your class was actually the first time I have really spoken out about my culture. In college I have never really had to talk about who/where I come from….Not that I do not want to talk about me being Asian American—I have just never been given the opportunity to do so. –Madelyn

I really enjoyed this family speech because I had the ability to tell my story through the lens of a Black American woman in modern times. Much of my culture has been tainted, assimilated, appropriated, and destroyed. That being said, this is one of the earliest accounts of history my people can recollect. Our history before slavery has been made to seem nonexistent. History books celebrate a white man’s “discovery” of a land that was already inhabited….This speech gave me a chance to showcase a tradition that my ancestors have been able to retain, pass down through generations, and receive recognition for their contributions….I believe allowing students to share cultural experiences and traditions in the classroom is highly effective in creating a more welcoming environment. Since students come from various backgrounds, being able to share their culture helps cultivate understanding and mutual respect. –Camryn

Freire (2005) discusses how a deficit approach to pedagogy, in which students who do not fit into the constructed cultural norm are perceived as Other, has long been used to assimilate marginalized students and maintain control over what constitutes knowledge. The deficit approach often prioritizes white, middle-class modes of communication in terms of dominant languages, literacies, and cultural practices. In contrast to the deficit approach, the Family Story and Family Objects Speech assignments invite students to share family stories in an academic setting, where such stories are not always brought to the fore alongside course materials.

One notable outcome was increased cultural competence, particularly for white students, who often see their cultural experiences as de facto or “neutral.” Many emails come in from white students asking for help on this assignment, to the effect of, “but I don’t have any traditions–my family is super normal.” Hearing an array of cultural experiences within and across visible differences challenges the idea that there is a “normal” experience. Many personal, often overlooked traditions came to the fore in the course of the speeches. Hearing many stories about celebrating Mardi Gras, going to crawfish boils, and going shrimping from a variety of students who grew up in South Louisiana created a sense of a shared cultural identity within and across various groups. Students who were not from the United States, or who were from other states, were quick to point out that going to crawfish boils was not “normal” to them. Thus, the stories help many students to recalibrate a sense of their own unique traditions.

A student demonstrates cultural knowledge by sharing their bait box for the Family Objects Speech assignment.

Devika Chawla (2017) argues that personal storytelling is an important performative practice of decolonial pedagogy. According to Chawla, autobiographical stories (including her own family immigration story) can serve as disruptions to Western colonial classroom norms. Chawla asks students to share their stories about family immigration in her majority-white classrooms and finds that these stories “are an invitation to the majority-white students to ask questions, to learn more about Other realities, and to interrogate their own family histories, rooted also in multiple migrations” (Chawla 2017, 118). We strongly agree with Chawla. Storytelling has been a gateway to intercultural learning and more equity in our classrooms. Below are excerpts from student responses in reflective writing about the assignment.

One speech I thought was really good was the girl who shared about her multiethnic family. I thought it was good because she really opened up about the struggles she went through and how people used to call her siblings “mutt.” It was brave of her to talk about that to the class. –Sierra

Hearing about my peer’s experience growing up in a very different culture in the Middle East made me realize America has its own culture, too. I haven’t travelled outside of the U.S. and haven’t thought about this much—how other people see us. –Anonymous

I heard speeches that had cultures and traditions I was familiar with (ex: growing up in Louisiana, being Catholic, coming from a big family, etc.); there were also many people whose cultures I did not relate to. One speech that stood out to me was Maddie’s. Something I thought worked in her speech was how her two items contrasted each other. They were both utensils (fork and chopsticks), yet their meanings contrasted [with] each other and how she grew up. One represents her white, more Americanized side, and the other represents her Asian identity. Her experience of growing up mixed and being told by her peers she was too “white” to act her culture was something that was eye opening to me. –Anna Grace

The array of family stories, and the similarities and differences in personal experience they brought to bear, helped us to clarify concepts in our curriculum moving forward. The stories allowed a point of departure for developing sociopolitical consciousness. We suddenly had a trove of student examples about critical cultural topics in Public Speaking: voice and dialect (what constitutes “proper” speech and whom does it benefit?), audience awareness (how can I account for a plurality of audience members’ experiences as a speaker?), and inclusive language (what terms are best for addressing a diverse audience?). These are important questions for students tasked with producing creative texts for public audiences. Having the touchstones of our family stories to kick off the semester made all these conversations more complex and more concrete. In one class, McDonald pointed out how many students talked about “my camp,” a patch of family-owned land where they grew up hunting and fishing in Louisiana. McDonald proposed thinking about land ownership in the context of racial heritage, pointing out that families of those with European ancestors were more likely to have received land or were encouraged to purchase land from the government in the 1800s and early 1900s, while families of those with enslaved African ancestors were more likely to have been denied access to land ownership altogether. One student knew the history of a relative who was granted lands through government programs in Virginia and used the money from their farm to buy the family camp in Louisiana. Some students, like Camryn, used the opportunity to raise consciousness explicitly about the historical significance of her family’s traditions:

The history of African American quilts is nearly as old as the history of America itself. Although long-ignored and absent from many early accounts of American quilt history, African American quilting has come to light…. Slave quilters not only made quilts for the owner’s family, they also made quilts for their personal use with “throwaway” or discarded goods as their material. The inner layer of quilts would often be filled with old blankets, worn clothes that could no longer be mended, or bits and pieces of wool or raw cotton. I come from a resourceful family steeped in tradition, pride, and talent. Being able to take scrap pieces to create something not only functional as a barrier to elements but also a work of art—creative and beautiful.

Although the assignment was generally successful, the transition from the Family Story Speech to the Family Objects Speech was challenging for some students. We found that students’ delivery for the warm-up speech was often stronger than the Family Objects Speech that came one or two weeks later. In the warm-up speech, for instance, student stories were often humorous and delivered in a relaxed, conversational manner. Many students spoke with enthusiasm and personality, as if they were recounting a precious moment with a friend. However, in the formal introductory speech, a much higher-stakes speech, many students seemed burdened by a sense of obligatory formality. Although the content was similar, many students delivered their second speeches with a sense of hesitation or rigidity not displayed in the warm-up speech. Students seemed to think their speeches needed to be “perfect,” and their fear of straying from “perfect” prevented a conversational delivery style. Perhaps simply having more points on the line resulted in students feeling more fear and less confidence.

In McDonald’s classes, students with varying dialects and accents from all over Louisiana even seemed to mask accents they previously used in the story speeches, falling into a forced Standard American English. Perhaps this points to classroom norms instilled by a deficit paradigm in education, which often lacks an appreciation for home languages, something teachers must actively counter. Baker (2002) insists that teachers must first establish respect for students’ dialects, writing:

I concentrate on how different forms of English are appropriate in different contexts, instead of relying on the right/wrong dichotomy students usually face in school. I do this because I want their own usage, vocabulary, modes of expression and their self-esteem to survive the language learning process (52).

We are left wondering: How can we further support students to bring their full selves into their major assignments? How can we better compose assignments that invite a full range of personal expression and also ask students to practice writing and composition skills that students need in various contexts? How can we invite students to think critically about the intersections of voice and power in education and culture?

We learned that performing a conversational delivery style is easier when telling a family story but becomes considerably harder to achieve when speech requirements are more complex. In future classes, we will have students analyze their own vocal performance to become aware of what is “natural” for them, and to honor a “home” voice while rehearsing for a higher-stakes performance. We believe that lower-stakes classroom speaking opportunities, such as the Family Story Speech, could play a strong role in pre-writing, narrative development, and delivery practice, especially when teachers can offer students feedback on what elements should be retained or revised in more formal speeches. One of the things that we hope students learn from this two-part assignment is that striking a compositional balance between organized and carefully crafted yet conversational and colloquial is truly an art, and speeches that nail this balance require extensive drafting and rehearsal. We observed that most students possess the ability to tell wonderful stories, and, with practice, these stories can develop into engaging narratives that support strong speeches. We hope that centering folklore in speech composition will help our students tell great stories, value their own and one another’s voices, and be heard.

Bonny McDonald, PhD, is a performance practitioner-scholar invested in cultivating community and classroom projects that address social justice topics with groups of all ages. She is Director of Basic Courses in the Communication Studies Department at Louisiana State University where she teaches courses in Public Speaking, Performance, and Communication Pedagogy.

Alexandria N. Hatchett is a PhD student in the Department of Communication Studies at Louisiana State University. Her research interests include rhetoric, critical/cultural studies, and critical communication pedagogy.

Works Cited

American Folklore Society. n.d. What Is Folklore? Accessed May 7, 2021, https://www.afsnet.org/page/WhatIsFolklore.

Baker, Judith. 2002. Trilingualism. In The Skin That We Speak: Thoughts on Language and Culture in the Classroom, eds. Lisa Delpit and Joanne Kilgour Dowdy. New York: The New Press, 51-61.

Chawla, Devika. 2017. Contours of a Storied Decolonial Pedagogy. Communication Education. 67.1:115-20.

Conquergood, Dwight. 2000. Rethinking Elocution: The Trope of the Talking Book and Other Figures of Speech. Text and Performance Quarterly. 20.4:325-41.

Freire, Paulo. 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Graves, Emily. 2015. Personal Interview. August 8. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 2014. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the Remix. Harvard Educational Review. 84.1:74-84.

—. 1995. But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Theory into Practice. 34.3:159-65.

Lyiscott, Jamila. 2014. 3 Ways to Speak English. TED, 4:29. June 19, https://youtu.be/k9fmJ5xQ_mc.

Paris, Django. 2012. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Needed Change in Stance, Terminology, and Practice. Educational Researcher. 41.3:93-7.

Valenzano, Joseph M., Stephen W. Braden, and Melissa A. Broeckelman-Post. 2020. The Speaker’s Primer. Custom Edition for Louisiana State University. Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press.