Pilgrimage

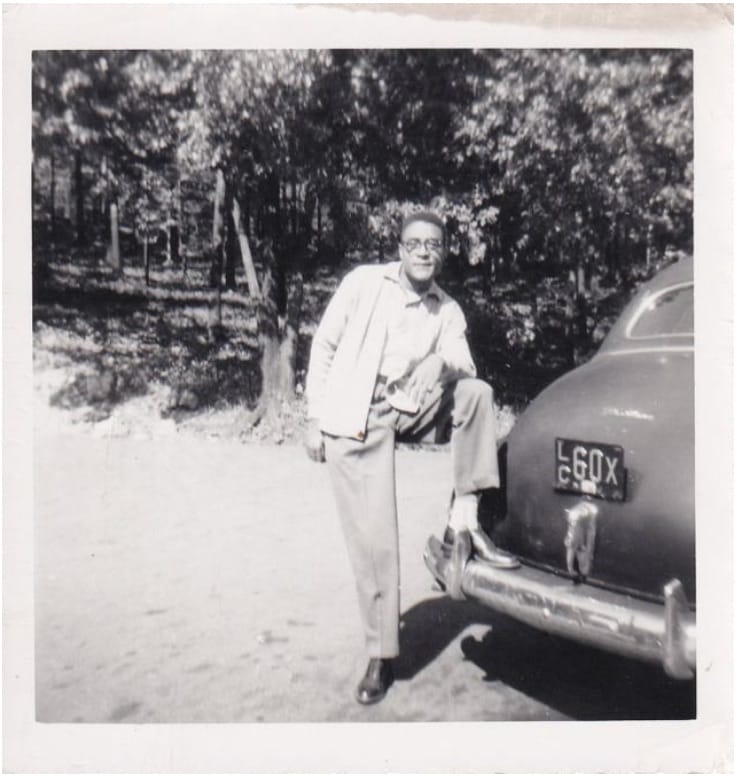

Daddy had spent the better part of two days washing, simonizing, and otherwise detailing our new car. It had to look extra-good, ’cause we were going on a big trip. All the kids on our street knew they had better make a wide berth around it as to not chance messing up his masterpiece.

The Georgia-bound 1947 chocolate-brown Lincoln cruised on fat white-walled New Jersey tires as it travelled down Route 301, with Daddy behind the wheel. It was crystal clear we would stop only for gas and to pee. That was Daddy’s rule.

The smooth wide leather bench seats were firm and comforting. We had driven over 600 miles, and I had been smelling the food in the box on the floor next to me the whole time. Mama had spent all yesterday making us her fabulous fried chicken, pound cake, and other delights wrapped in wax paper and aluminum foil. She covered it all with dish towels, then neatly packaged everything in a good-sized cardboard box. I’m here to tell you that box just couldn’t hold the smell in!

On the floor with it was the big green Aladdin thermos jug with sweet orange-lemonade Mama and I made the day before. I rolled the lemons for her to make them soft so they were easy to squeeze and juicy. Just thinking about the taste of that drink made me thirsty, but I knew better than to ask. Drinking meant stopping to pee, and I remembered Daddy had special rules about when to stop the car. He was in charge of all rest stops!

It was 1953 and I was a six-year-old child in the days of no seat belts. I hung onto the thick, heavy fabric cord safety strap loop mounted on the side panel between the front and back doors. On the backseat next to me lay Mama’s Bible and hymnbook as well as my picture-and-word Golden books. I loved to read and preferred them over toys—so they made the trip with us.

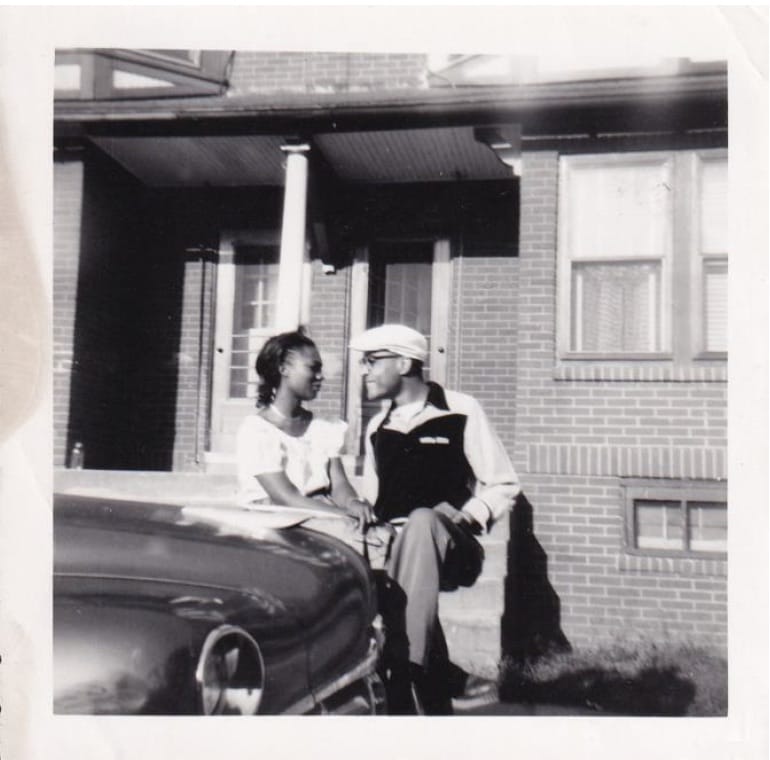

Standing with both feet on the backseat, arms overhead with hands hooked in the strap, I leaned sideways resting my head against the back of the front seat, which held my summer-straw-capped father and my flower-dressed, comb-filled-pompadoured mother. Mama would start a hymn and Daddy would add his bass harmony from time to time. There were lots of funny stories about the relatives we were headed to see. Daddy and Mama were going back home for a visit. We were all so happy.

This morning started as all the yearly summer southern pilgrimages would for years to come. Daddy had placed our stuffed luggage in the trunk of the car along with presents for the relatives we would see soon. He had to be real careful not to upset Mama, because if he crushed her hatboxes, somebody was going to hear about it for a long time after. That somebody would be Daddy, of course, but I would be in earshot.

Mama would begin, All those hours, all that time and money, shopping for materials, creating designs, making hat forms from wooden molds, cutting, sewing, gluing! Have mercy, Jesus!

Suffice it to say, the luggage always went in first and the hats (her one-of-a-kind showpieces) last. On the other hand, my father’s felt fedora and bowler hats always made the journey inside the cabin with us, prominently displayed in the rear window behind the backseat.

Before the trip began, once we were settled in our seats, the second early-morning prayer began with us all holding hands. (The first and longer version had been said in the living room of our house.) It was still dark outside. I remember the sound of crickets and peepers from the Assunpink Creek not far from our house.

Dear Father God, we humbly come before you this morning seeking traveling mercies, knowing that you can do all things and are all powerful. We beseech you to wrap us in your loving arms, Jesus! Hold us, Father! Build a fence around us, Father, that no man can put asunder! Keep us, Father, from all hurt, harm, or danger! These things we ask in Jesus’s name, Amen.

We never left without a prayer of safety and protection raised.

I had slept for a while, but now my backseat standing position gave me a wide view of the increasingly southern panorama. Trees, flowers, crops, chickens, cows, billboards, roadside stands, gas stations, and restaurants flashed by. The billboard pictures had lots of children. Huge heads of a boy and a girl next to a big bag of bread with colorful dots I recognized as Wonder Bread. A yellow-haired baby on a beach looking back at a puppy dog pulling at her pants exposing her very white bottom puzzled me. There were aproned moms serving their families, dressed up ladies with hats and fur stoles, and lots of men with rosy cheeks smoking cigarettes and pipes who were laughing. I delighted in repeatedly seeing the big, smiling, sombrero-wearing man announcing the number of miles to reach “South of the Border,” the one scheduled stop Daddy would make.

Reading these signs was a pastime for us car folk. Daddy would read one, then Mama, then I would get a turn. I was a good reader, but most of the signs had too many words for me to read at the speed we traveled.

The Burma-Shave signs, however, were my favorites—small, white, one-word signs with black lettering. These words were digestible even to a child. One or two words per sign spaced several consecutive yards apart made up a whole sentence that always finished with the words “Burma-Shave.”

“Have a date? Don’t be late! Burma-Shave!” “For faces that go places, Burma-Shave!” “Aid the blade! Burma-Shave!” “Look spiffy in a jiffy! Burma-Shave!” “When you shop, for your pop, Burma-Shave!”

There were other signs that looked like Burma-Shave signs, but they were not. These signs were always on the sides of gas stations and restaurants–small, white, one- or two-word signs with black letters. I felt proud that I could read them. When I read them out loud, it got real quiet in the car. I felt the air change. Daddy cleared his throat, took off his cap, and shifted in his seat. Mama’s head got real still, but I couldn’t make out what these signs meant.

After passing and reading several of them out loud in a row, I finally asked, “Mama, what do they mean? What are they for?”

My mother turned toward the backseat and me and said with a thunderclap, “Sit down, be quiet, and eat some chicken!” I knew “happy” had left our car.

We rode on in silence and the air stayed heavy for a long time. Finally, Daddy decided it was time for a rest break. He pulled off the highway to the side of the road with some high grass on a slight slope and a stand of tall trees further in. Mama and I took toilet paper and went into the tall grass near the car and lifted our skirts, squatted, and did our business.

Across the road was a large, open field with crops already high. Daddy got out of the car and stood up real straight. He put his cap back on, lit a cigarette, and leaned his back against the car frame, arm slung over the open driver’s door, and gazed over the crops in the open field, momentarily lost in memories he had chosen to forget.

He was coming Home.

Author’s Note

Jim Crow and the promise of gainful employment gave Southern Blacks a reason to participate in mass migration to Northern urban centers. But not everyone left, and longing for family who stayed South, traditions, and things familiar occasioned many “new” Northern Blacks to return home to rejoin family ties and old ways of being. Not everyone who returned home had a “Green Book” to guide them, and the 1940s, 50s, and 60s were perilous times on Southern U.S. roads for Blacks in shiny new cars with Northern license plates. This story talks about what it was like driving back “down South” for such a family without aid of anything but prayer, vigilance, natural wits, and foreknowledge of southern ways.

In general, I write because the faces and voices of so many elders are fading, like an old photograph left too long in the sun. So many stories have never been and never will be told because when an

elder who held them dies, a library is lost. Many people did not tell their stories because they were too painful to remember and they did not want to burden their children with them. For some, part of breaking free is leaving behind the past.

I write because I believe all stories are important. Stories help us know who we are and who we have been as a people, as a country. The small stories of ordinary people knit us together and break us apart. Everyday revelations (stories) illustrate truth unimpeded by vanity. Stories show what human nature sees (reveals), including the threadbare cloth of lies, allowing us to feel their bumpy texture inside and out. When we can capture them, we must pass the stories on, and the people will not be forgotten. It is essential for the human race to learn from those who have gone before us. We must pay attention and always try to do better, because as humans we have that capacity, and that’s our job. Our ability to thrive is tied to this concept. To do otherwise guaranties self-destruction.

I call my work “framing the past in the peace and possibility of the present.”

Vicie A. Rolling lives in upstate New York. As a retired Professor of Health and Wellness she has gone on to more artistic pursuits. She is a “StoryCatcher.” Her avocation is storytelling that includes poetry, short stories, and historical reenactment. She works as a teaching artist in a variety of settings including, schools, museums, historical societies, churches, and festivals. She has produced two chapbooks and two CDs of poetry and short stories. For information email info@framingthepast.com.