National Heritage Fellows (left to right) Chitresh Das (2009), Norma Miller (2008), Agustin Lira (2007), Evalena Henry (2007), Frank Newsome (2011), Qi Shu Fang (2008).

All photos by Alan Govenar.

Photographs can document the skills and art forms that individuals and communities recognize as integral to their folk traditions, but in today’s ever-changing world how that documentation engages the viewer and affects the people it documents raises difficult questions. Over the last 35 years my documentary approach has evolved as a result of the widening scope of my ethnographic experience and the dynamic landscape of technology. When I started doing fieldwork in the 1970s, I had little experience using photographic equipment. Within the scope of my academic training in folklore and anthropology, I understood the importance of photography but had not developed the fundamental technical skills I needed to document the folk artists and the communities I was observing and interviewing.

I bought an inexpensive 35mm film camera and started to experiment with different approaches. Through consultation with others working in the field and through trial and error, I gradually acquired the technical competency needed for my work as a public folklorist. I began to understand the ways photography needed to integrate with other fieldwork methods. Talking about photography often deepened my dialogue with the folk artists I was interviewing. Asking to see their scrapbooks and family photographs expanded our conversations and provided a bridge for discussing my interest in photographing them.

The most difficult part of photographing a fieldwork setting was encouraging folk artists to try to detach from the camera and to work or perform as they normally did. It was helpful to have other people present, especially family members or friends. However, some people simply didn’t like being photographed, and when they were in front of the camera they tensed up and were accustomed to posing. In other instances, it was necessary to take a break or to return at another time to make photographs. Photography is inevitably subjective through the process of framing, composition, and lighting, but it is also affected by the nature of the interaction between the photographer and the subject of the photograph.

My goal when conducting fieldwork was to document the work of exemplary folk artists and to explore the ways that folk and traditional arts were passed on from one generation to the next. One exhibition I organized in 1981, titled Ohio Folk Traditions: A New Generation, featured the work of established artisans alongside that of their apprentices. In my photographs, I emphasized the interaction between generations and strove to establish the context in which folk artists lived and worked.

My involvement with the National Heritage Fellowship Program of the National Endowment for the Arts began during this period. One of the first individuals to receive a National Heritage Fellowship in 1982 was Elijah Pierce, an African American woodcarver who had a barbershop around the corner from where I was then teaching at Columbus College of Art and Design in Columbus, Ohio. Each semester, I took students on fieldtrips to Pierce’s barbershop to meet him and to watch him work. My photographic documentation, limited as it was, focused on Pierce and his apprentice Leroy Almon. Looking back, I would have done more to document the process through which Pierce made his woodcarvings, focusing perhaps on an individual piece from start to finish and exploring how the completed work was shared, sold, or displayed. In addition, I would have examined more closely his relationship to his community and his daily interactions with those people who frequented his barbershop and the cultural dynamic through which his woodcarvings attained meaning.

After founding the nonprofit organization Documentary Arts in 1985, my thinking about photography advanced. With each new generation of cameras, I challenged myself to develop the necessary technical expertise to put this equipment into use. However, during the 1980s the purpose of my documentation focused largely on the development of public programs. Between 1981 and 1991, I organized six Dallas Folk Festivals; developed a folk artist residency program in the schools; produced three 13-part Traditional Music in Texas radio series; compiled and released a series of audio recordings of local African American, Asian, Mexican, Native American, and Anglo musicians; and produced and directed documentary films for broadcast and educational distribution. In conjunction with each of these public programs and media projects, I made photographs that were featured in exhibitions; published in books, articles, brochures, and posters; and also disseminated to local communities and the public at large. I aimed to develop an infrastructure for involving local communities. With the support of grants from governmental agencies, as well as from private and business contributions, Documentary Arts gave honorariums to the folk and traditional artists who participated in its public programs and media projects. We secured signed releases, enabling us to make our documentation as widely accessible as possible, and we created a mechanism for individuals and communities to use the documentation we produced free of charge. Documentary Arts distributed its audio recordings to students, teachers, schools, libraries, museums, and community centers, and the performers featured on our cassette and later CD releases were paid 50 percent of all net profits, instead of a conventional royalty that a commercial company might have provided. During this period, photography was a tool that complemented the implementation of public programs.

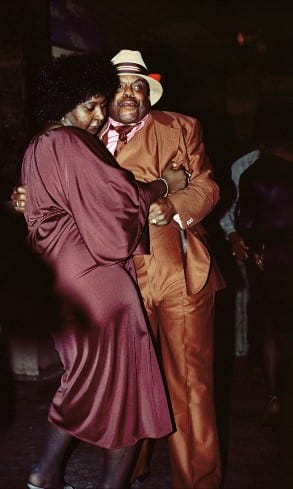

Couple dancing, Longhorn Ballroom

Dallas, Texas, 1984.

I became more aware of the ways that different cultural groups document themselves by investigating how photography is made, presented, and displayed in people’s homes, as well as in public places of work, education, worship, and fellowship. To explore the distinction between photography as evidence and photography as a manifestation of shared values and beliefs, I have used an interdisciplinary methodology that draws from the fields of folklore, popular culture, anthropology, and history to challenge existing formalistic approaches. In so doing, I have developed the concept of community photography to understand better the work of African American photographers in Texas who actively documented the world in which they lived and worked, focusing on those events, ceremonies, and activities that were integral to the daily life of the people they served, from baptisms, weddings, and funerals to homecoming parades, graduations, and family reunions. In 1995, my wife, artist and feminist arts advocate Kaleta Doolin, and I founded the Texas African American Photography (TAAP) Archive to preserve and present the work of photographers whose work had been overlooked by mainstream cultural institutions.

Photographers represented in the TAAP Archive, like Alonzo Jordan in Jasper and Eugene Roquemore in Lubbock, were not professional per se. They worked day jobs, Jordan as a barber, and Roquemore as a janitor, but both recognized the importance of photography as a means to bolster identity and self-esteem by documenting and sustaining oral memory through the visual representation of personal experience and community traditions. In this way, the photographs they produced embodied the values and beliefs of their subjects. While the photographers were usually compensated for their efforts, they often donated their time and services to individuals in their communities who might not otherwise be able to afford them. The photographers were highly regarded, not only because of the quality of the images they made, but also as a direct result of their commitment to the enrichment of their respective communities.

In my own documentation, I started to rethink the premises that were the basis of my photographic work. While I recognized the importance of context and performance to elaborate the ways that individuals and cultural groups interact and present themselves, I began to explore the significance of the portrait and how perspective, framing, lighting, and composition of the image were linked to perception and recognition. Photographic portraiture is rarely discussed as a best practice in cultural studies. Yet, portraits are probably the most common form of photographic documentation. Portraits are displayed proudly in people’s homes, schools, businesses, governmental buildings, and places of worship. Portraits are both public and private, ceremonial and intimate. We see them virtually everywhere we go, and we carry them in our purses and wallets, on our screen savers and cellphones.

In the 1990s I began making photographic portraits in earnest, experimenting with different methods and equipment, using both film and digital cameras and creating images in black and white and color. I photographed individuals and groups in different settings, from living rooms and hotel rooms to backyards and expansive natural environments.

Then, in 1997 I printed my first human-sized photographs for an exhibition at the African American Museum in Dallas and began to recognize their potential. In 2005, my wife Kaleta had the idea to purchase a Hasselblad camera with a 39-megapixel digital back that had just been introduced. With this camera and its technological advances, my capacity as a photographer expanded exponentially. I started making human-sized photographs of the National Heritage Fellows because I felt that seeing these individuals face to face might engage the viewer in unexpected ways. I tried different color backdrops and settings and finally decided that a neutral black background was at once the least intrusive and the most evocative. I was particularly interested in the ways that individuals presented themselves in street clothes as well as in the trappings of their cultural heritage. I encouraged each individual to pose as they wished and then gave them the opportunity to see themselves as they appeared in the photograph, often talking with them about how portraits can express the core of who we are or aspire to be. The immediacy of a high-resolution digital image on a computer screen heightened the experience, and frequently the subjects, after seeing themselves, wanted to pose differently.

The resulting decontextualized portraits emphasize the inherent equality of all people and cultures. Looking at these human-sized prints invites the viewer not only to reconsider preconceptions about cultural identities, but also to reflect on continuity, transfers, exchanges, and transmissions in the living heritage of communities, groups, and individuals. Face to face we are encouraged to interact with the people before us and to participate in the fundamental process of recognition that is so essential to our culturally rooted traditions and to our comprehension of the world in which we live and work.

In a decontextualized portrait, the viewer must see the subject as a person in his or her own terms. Portraits involve direct communication not only between the photographer and the subject resulting from a dialogue, and perhaps negotiation or intervention, but also between the viewer and the person represented in the final print. The portrait commemorates achievement in a form that is easily understood, but when seen full-body and human-scale the image is imbued with added significance through its detailed expression of human dignity.

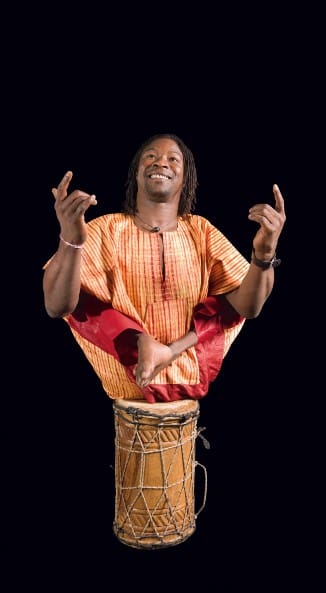

Sidiki Conde, Washington, DC 2007.

In my own work, portraiture has provided opportunities to engage in a dialogue with National Heritage Fellows that has energized more in-depth study and documentation. My portraits, for example, of Sidiki Conde led me to photograph Sidiki and his day-to-day life in New York City over the next several years. I photographed Sidiki in his apartment, on the street, and in workshops he conducted for disabled children. These photographs then became the basis of my feature-length documentary film You Don’t Need Feet to Dance. Today, Documentary Arts helps to fund Sidiki’s work teaching disabled children at the Brookville Center in Brookville, New York.

Over the years, my work with Documentary Arts has become increasingly more holistic through an interdisciplinary approach. My feature-length film Extraordinary Ordinary People features more than 75 recipients of the National Heritage Fellowship and demonstrates the importance of the folk and traditional arts in shaping the fabric of the United States. From Bill Monroe and B.B. King to Passamaquoddy basket weavers and Peking Opera singers; from Appalachia and the mountains of New Mexico to the neighborhoods of New York, the suburbs of Dallas, and the isolated Native American reservations of Northern California—the artists share exceptional talent, ingenuity, and perseverance. In addition, the Documentary Arts website Masters of Traditional Arts includes more than 4,000 photographs, 550 video segments, 30 hours of interviews and audio recordings, as well as an education guide with free downloads and biographical entries on National Heritage Fellows, 1982-2016. Again, my hope is that by making documentation freely available people will encounter the humanity as well as the artistry of folk and traditional artists.

Classroom Connections

- The Masters of Traditional Arts Education Guide is a dynamic, interdisciplinary tool designed for teachers featuring stories, cultural context, and media of the NEA National Heritage Fellows.

- Local Learning hosts lessons featuring Alan Govenar’s portraits to explore connections between dress and culture. See also his article in Journal of Folklore and Education, Volume 1 (2014).

Sidiki Conde leading an after-school workshop, Manhattan School for Children, New York City, 2011.

Sidiki Conde boarding a bus, New York City, 2011.

With the technological advances of the 21st century, the possibilities of photography have expanded exponentially. Cameras have never been more accessible, and the technical quality of the photographs made by professionals and amateurs alike continues to improve. While professional photographic equipment can aid the process of documentation, it may also be imposing and, perhaps, culturally inappropriate. Using a point-and-shoot pocket camera or a cellphone camera may be readily accepted, but a sophisticated SLR camera with a zoom lens may be threatening in certain situations. More study is needed to assess the extent to which different photographic technologies and the expertise to use them affect the documentation of folk traditions and how the resulting documentation is perceived and understood by those being documented and those studying and viewing the documentation. Moreover, the aesthetic qualities of photography may be as important as its content to folklorists and cultural specialists and to the individuals and communities who are the focus of documentation. Striking a balance between the photograph as art and as artifact may be necessary to catalyze the viability of folk traditions through the awareness and the dialogue that the image engenders.

Alan Govenar is a writer, folklorist, photographer, and filmmaker. He is a Guggenheim Fellow and president of Documentary Arts, a nonprofit organization he founded in 1985 to present new perspectives on historical issues and diverse cultures. He has a BA in American Folklore from the Ohio State University, an MA in Folklore and Anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin, and a PhD in Arts and Humanities from the University of Texas at Dallas. He is author of 30 books and has produced and directed numerous films in association with NOVA, La Sept/ARTE, and PBS for broadcast and educational distribution. His artist books and photographs are in collections in the U.S. and abroad, including The Museum of Modern Art, Victoria and Albert Museum, Centre Georges Pompidou, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, National Portrait Gallery, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

URLs

https://www.arts.gov/honors/heritage

http://www.docarts.com/archive.html

http://www.docarts.com/you-dont-need-feet-to-dance.html

http://www.docarts.com/extraordinary-ordinary-people.html

www.mastersoftraditionalarts.org

http://www.mastersoftraditionalarts.org/education/preface

https://www.locallearningnetwork.org/education-resources/national-heritage-fellows