Teaching toward Equity through Collective Songwriting at the Yakama Nation Tribal School

by Kaity Cassio Igari, Juliana Cantarelli Vita, Jack Flesher, Cameron Armstrong, Skúli Gestsson, and Patricia Shehan Campbell

Under dimming gym lights, an audience of teachers, students, and families shifts eagerly into place as high schoolers fill the stage. Brimming with anticipation, Yakama Nation Tribal School students pick up drums, guitars, and violins, preparing to share the songs they have been crafting over the last four months. University of Washington musicians bustle in the background, hovering over computers, whispering final reminders about entrance cues, and attempting to calm band members’ nerves. After introductions by Yakama and university Elders, the moment finally arrives—raising their instruments, breathing deeply, the students lift their voices and begin to sing.

Twenty years ago, Yakama Nation Elders and University of Washington (UW) music education leaders forged a partnership called “Music Alive! In the Yakima Valley” (MAYV), a cultural exchange program to share music and promote equitable education. After a brief hiatus, UW-affiliated experts in popular music and collective songwriting returned to Toppenish, WA, in 2018 to facilitate youth songwriting at the Yakama Nation Tribal School (YNTS).1 Since then, UW and YNTS students come together each year to create music that explores and celebrates students’ identity as Native youth, culminating in the composing, recording, producing, and performing of songs.

The current cultural partnership program is rooted in two complementary processes; the first is testimonio, followed by collective songwriting. In a contemporary example that inspired our project, activist and scholar Martha Gonzalez used testimonio in her project Entre Mujeres: Women Making Music Across Borders, in which women expressed their lived experiences as migrants. The testimonios were eventually turned into songs and recorded on an album (Gonzalez 2015). This brings us to our second process, collective songwriting, in which the testimonio is translated into lyrics and gains new life through rhythm and melody. These two processes uplift individual and community identities by honoring student experiences and, further, synthesizing their interests in contemporary popular music, dance, poetry, and Indigenous traditions.

Testimonio is a process of transmitting lived experiences into a literary form. Birthed in Latin America, the exact genesis of testimonio is not defined by a specific moment or event but has been alive since the 1970s; it is a literary mode associated with acts of liberation, specifically related to resisting imperialism in developing nations (Reyes and Rodríguez 2012). In Chicana and Chicano education research, testimonio is concentric with Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s liberationist pedagogy, which uses the learning of literacy as a tool of liberation. Jointly, liberationist pedagogy and testimonio “empower the speaker or narrator to transform the oral to its written representation not as an act of oppression and ignorance, but rather as an acknowledgment of the revolutionary aspect of literacy” (Reyes and Rodriguez 2012, 527). Testimonios have historically come in many forms such as speeches, newsletter columns, corridos, or spoken word.

Our program sought to use pedagogy that worked with, not against, ways of learning, knowing, and being within the Yakama Nation. Opportunities for students to develop their individual and community identities within the tribe already existed and became a crucial part of both the testimonio and collective songwriting process. The Yakama hold weekly cultural nights when young people and adults share meals, practice pow-wow dancing, and participate in traditional drumming and singing (Campbell et al. 2019). The cumulative pedagogical processes of testimonio and collective songwriting are rooted in the act of sharing lived experiences, therefore these processes are not only congruent with current Yakama traditions, they also further amplify student voices as they express their Native identities in conjunction with their intersecting identities as modern youth.

Participating students relay personal experiences on and off the Reservation, developing their expressive-creative voices as Native people in an empowering musical setting. During six or seven half- and full-day sessions, YNTS students compose songs to share with the tribal community, incorporating Indigenous Yakama musical expressions and Ichiskíin2 language, while working with YNTS teachers and Elders to craft lyrics and drumming. Each year’s workshops culminate in a live performance and digital song sharing.

We aim to reflect collectively, with consultation from YNTS leadership, on our experiences as activist-music educators celebrating collective songwriting as a powerful decolonizing pedagogical approach, intent on pushing back against the institutionalized curricular inequities of the American music classroom. We write collaboratively, each bringing unique perspectives to our understanding and support of decolonizing practices. We highlight the process of this project, informing how other musician-educators may explore similar practices in teaching and learning for equity. Using narrative description, we reflect on particular moments through the lens of Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s decolonizing dimensions of research (Smith 2012). Decolonization has emerged in educational circles as a movement to confront and challenge oppressive systems, so we attempt to root our article in this rich, dynamic current of Indigenous theory and practice. Smith’s dimensions delineate the purpose of our workshop by defining decolonization as not merely consciousness raising, but also as a multidimensional approach to disrupt settler-colonialist and capitalist practices, reprioritizing Native sovereignty and cultural values (Smith 2012). This approach also connects to Lee and McCarty’s (2017) three components of critical culturally sustaining/revitalizing pedagogy: recognizing “asymmetrical power relations” toward transformation, “reclaiming and revitalizing traditional practices,” and embracing “community-based accountability” (Lee and McCarty 2017, 62).

From an understanding of the struggle of decolonization as dynamic, collective agency, Smith argues for the complex interplay of critical consciousness, reimagination, disparate cultural and social elements combined, counter-hegemonic movement and disturbance, and challenge to power structures. Decolonizing efforts, then, move beyond individual moments of healing and into communitywide conditions and actions that support collective liberation from oppressive systems. We describe Smith’s overlapping dimensions in the following order: (a) disparate elements combined, (b) counter-hegemonic movement, (c) critical consciousness, (d) structures of power and imperialism, and (e) reimagination. The project seeks to be “an activity of hope,” an “effective political project . . . [to] touch on, appeal to, make space for, and release forces that are creative and imaginative” (Smith 2012, 322-23).

The Combination of Disparate Elements: Creative Chaos toward Building Community

This section considers the distinct elements of the project that combine to build community. This dimension of decolonization is “the coming together of disparate ideas, the events, the historical moment, which ‘creates opportunities’ and ‘provides the moments when tactics can be deployed’” (Baldy and Yazzie 2018, 5; Smith 2012, 320).

An average day in the collective songwriting program is chaotic. Handfuls of YNTS students trickle into the classroom while we, the UW team, connect speakers, gather materials, and wrestle the Wi-Fi. Some students participate enthusiastically in beat and movement warm-ups; others lean back in their chairs, checking the Snapchat app on their mobile phones. Transitioning into large-group conversation, students might be reticent or volunteer comments about their school, traditions, and community concerns. YNTS staff listen quietly in the background or join in the brainstorming and pop music singalongs. During breakout sessions, sounds of drums, guitars, free-styling, and beat-making overflow. After breaks, raucous song planning resumes as students yell out ideas for “hooks” and try them to various beats, performed on drums or sampled from a computer. Students might leave at the lunch bell or linger until conversation and jamming fizzle out. After leaving YNTS, we debrief over coffee, gathering the threads of the day for the next visit.

The program’s primary elements are the students and their community. YNTS is expressly committed to educational achievement and cultural preservation for 8th-12th graders. Teachers ensure academic activities align to state learning standards while supporting students’ acquisition of traditional language, culture, and history. “The kids need to realize ‘I have something to contribute,’” culture teacher Ezilda Winniers shared. Through traditional seasonal activities, mentorship programs at a local college, dance and drumming performances, all-school opening and closing circles, competitive basketball teams, and the collective songwriting project, students have the opportunity to do just that. Students are members of youth and tribal communities and take obvious pride in their school, for example, planning a music video for a recent collective song to highlight “a day in the life of a student,” with “fun and friendship.”

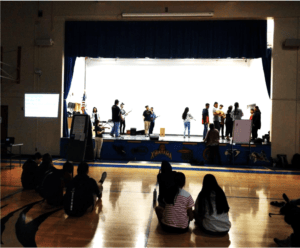

Figure 1. Electronic beats and instruments, acoustic violin, and Yakama drumming come together in performance.

Other elements are the UW facilitators. We are experienced music educators, ethnomusicologists, and performing musicians, working in local and global school music programs and community music settings. Our diverse backgrounds—international elementary classrooms, secondary and tertiary bands, studio lessons, American Roots music, Brazilian Maracatu, various styles of folk and traditional music, and international rock performance—along with strong commitments to intercultural exchanges, prepare us for making music in myriad styles. Team membership shifts with funding, with some members constant throughout. From the original two to this year’s conglomerate of five graduate students and one faculty advisor, we bring distinct strengths to our planning, facilitation, and student interactions. We lead breakout sessions based on our skills and alternate guiding songwriting, documenting the process, or engaging with students on the fringes. The addition of female facilitators proved significant. On one visit, two returning male facilitators led discussion and musical planning with confident returning students (mostly male), while two female facilitators huddled with new students (mostly female) and relayed their whispered responses to the group. During one lunchtime conversation between the female facilitators, a YNTS student teacher, and Ezilda, she emphasized the importance of providing strong female role models to help students develop self-confidence and self-esteem. The next year, the returning female students led discussion, prioritizing their favorite musical styles and insisting on attention to the missing and murdered Indigenous women.

The collective songwriting project is also intergenerational and multilingual. Students work with Ezilda and Elder Tony Washines to translate lyrics into Ichishkíin, with Ezilda calling on her own Elders to finesse the grammar. Students combine multiple musical styles, from Yakama drumming to rap and country styles, weaving diverse preferences into a personal musical setting (Figure 1). Their music also connects the broader school community through all-school performances and recordings shared on social media or local radio. A YNTS teacher applied a collective song to a basketball tournament slideshow, even making videos on the TikTok mobile app with it.

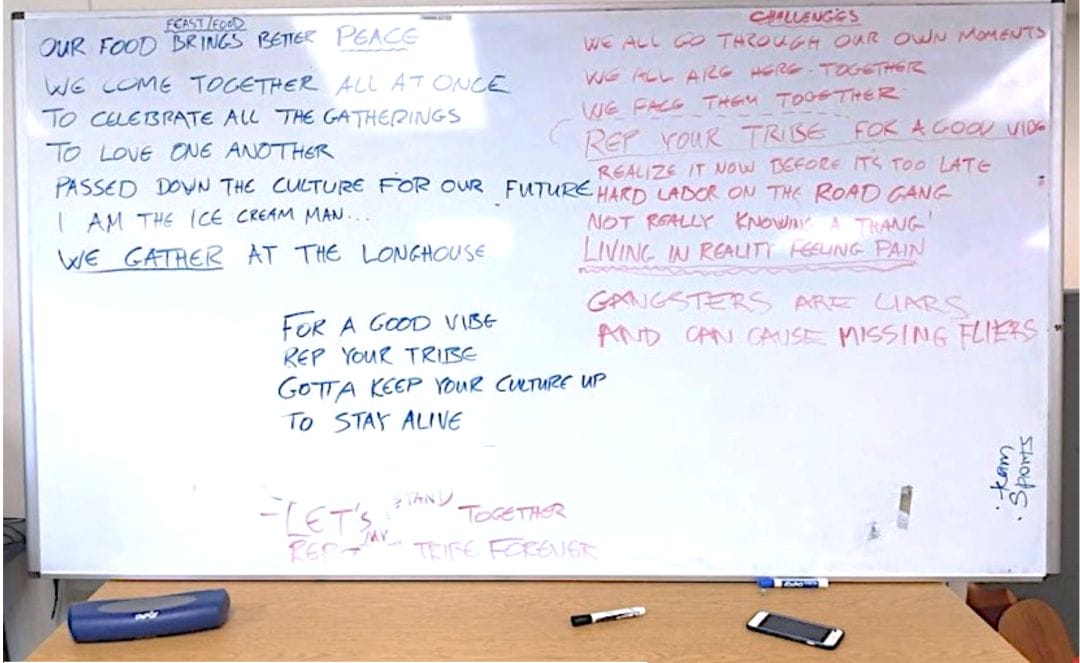

After one songwriting session, a pep assembly celebrated both the women’s and men’s basketball teams making it to the state playoffs. Basketball is a source of pride at YNTS, with coaches and players diligently fostering athletic achievement and sportsmanship. As they prepared to go to the state tournament, the whole community cheered them on. At the suggestion of a YNTS teacher, the students’ collective song blasted through the gym and everyone sang along (Figure 2):

For a good vibe, rep your tribe

Gotta keep your culture up to stay alive

Let’s stand together, rep my tribe forever

Figure 2. Lyrics from the 2019 collective song.

Counter-Hegemonic Movement: Transversing Pride and Sites of Struggles

The creative chaos that is very much part of building community within this project happens hand in hand with the duality of counter-hegemonic movement, as students share that space for transversing pride and struggle. The collective songwriting project at YNTS, much like the efforts of the school itself, is engulfed in counter-hegemonic tendencies as students share in poetry and music their struggles and reasons to celebrate as a community that belongs to both tribal and youth cultures (Campbell et al. 2019). During a visit in the winter of 2020, while students were at the computer lab creating “beats” with audio interfaces and MIDI keyboards, another group was playing with possibilities for a music video. Standing tall on tree stumps and making a human alphabet with the letters Y-N-T-S on top of the baseball field bleachers, the idea was to portray their favorite school campus spots, connecting to the song they were writing.

Figure 3. Students performing a Māori stick game.

Throughout this process, students raised issues of cultural loss between generations, while responding to ways to tackle these issues, such as being role models within their community. In the context of the tribal school, these discussions provided a space where students could call upon their experiences as Native individuals to formulate new approaches to the issues their communities face. In one of the early workshops, students at YNTS learned and explored a Māori stick game, while singing in Māori language (Figure 3). This particular activity normalized languages other than English for creative production. This process aligns with the aims of the tribal school to fortify Ichishkíin within the younger Yakama members and to close the language gap, as it is spoken mostly by community Elders but not by most parents of the tribal school students. In a later visit, when invited to choose a new song to go with the stick game, students were quick to pick a popular song they like to listen to (“Home,” by Phillip Phillips) as a mashup of traditional Māori culture and the musical world they live in mostly and value.

Students also explore counter-hegemonic opportunities to disrupt gender norms across tribal and global youth identities within the collective songwriting project. Operating as a culturally safe space for gender exploration and solidarity, the program allows students to question and disturb the status quo within the school community through their music-making process. One activity of a three-day workshop involved breakout sessions (lyric-making and guitar) and all girls decided to play guitar. Under the guidance of one of the female UW team members, the all-female group learned a few basic chords and strumming patterns and some extended techniques such as tapping a percussive rhythm onto the body of the instrument. From there, they wrote a song with the chords, strumming patterns, and extended techniques they had worked on to perform for the whole group. After a few surprised reactions from the other students when the often-quiet girls returned to the room with a whole new song created on their recently learned instruments, it was hard not to notice the celebration from the whole group—and the girls’ boosted confidence and assurance—after their performance.

Critical Consciousness: “Awakening from the Slumber of Hegemony”

Counter-hegemonic movements are further fortified when accompanied by critical reflection. Critical reflection is a social justice pedagogy that encourages students to question social arrangements and structures to become attuned to their sociopolitical, and socioeconomic circumstances (Freire 2000, 48). Beginning in the 19th century, hegemonic educational injustices against Indigenous communities began with U.S federal boarding schools, whose administrators and teachers often banned Indigenous music and culture from education with the intent of breaking down tribal relationships (Shipley 2012). Euro-American traditional music was even used as an agent of cultural assimilation for Native youth (Hill 1892; Campbell et al. 2019). The reality of this contentious hegemonic oppression remains present and palpable and can be felt in the lyrics of YNTS students who wrote and sang the critical and poetic prose, “The tribe that has experienced the worst is the tribe that has always been here the first.”

The genesis of a collectively written song stems from the collective sharing of testimonio, a generating of ideas, each born through the lived experiences of those involved, and eventually synthesized into a collective artistic artifact. At YNTS, this process begins with providing students general and open-ended questions such as “What’s important to you?” and “What are issues in the community?” At first students are hesitant, mumbling typical teenage responses like “sleep,” or “mac n’ cheese.” But the tone and atmosphere eventually shift as concerns of tribal alcoholism and drug abuse rise to the surface. Soon to follow are passionate descriptions of what seem to be critical matters on students’ minds, including the prominent societal issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW).3 Moreover, preservation of tradition emerges as students speak of tribal identity in the form of pow-wows, drumming, and fry bread. This act of sharing individual and community concerns manifest in a tree of ideas, with one thought branching out into many more, produced by collective minds, and sprawling across a large whiteboard.

Collective songwriting in classrooms is an act of pedagogical equity and social justice, encouraging students to become truth-tellers and change-makers, with teaching practices that make space for students to become aware of historical injustice and feel connected to a legacy of defiance (Bigelow et al. 2004, 3). This manifests in an excerpt from YNTS students:

Land is our pride and joy

Our land is sacred and

Is not to be destroyed

…We stand for our land tonight (Campbell et al. 2019)

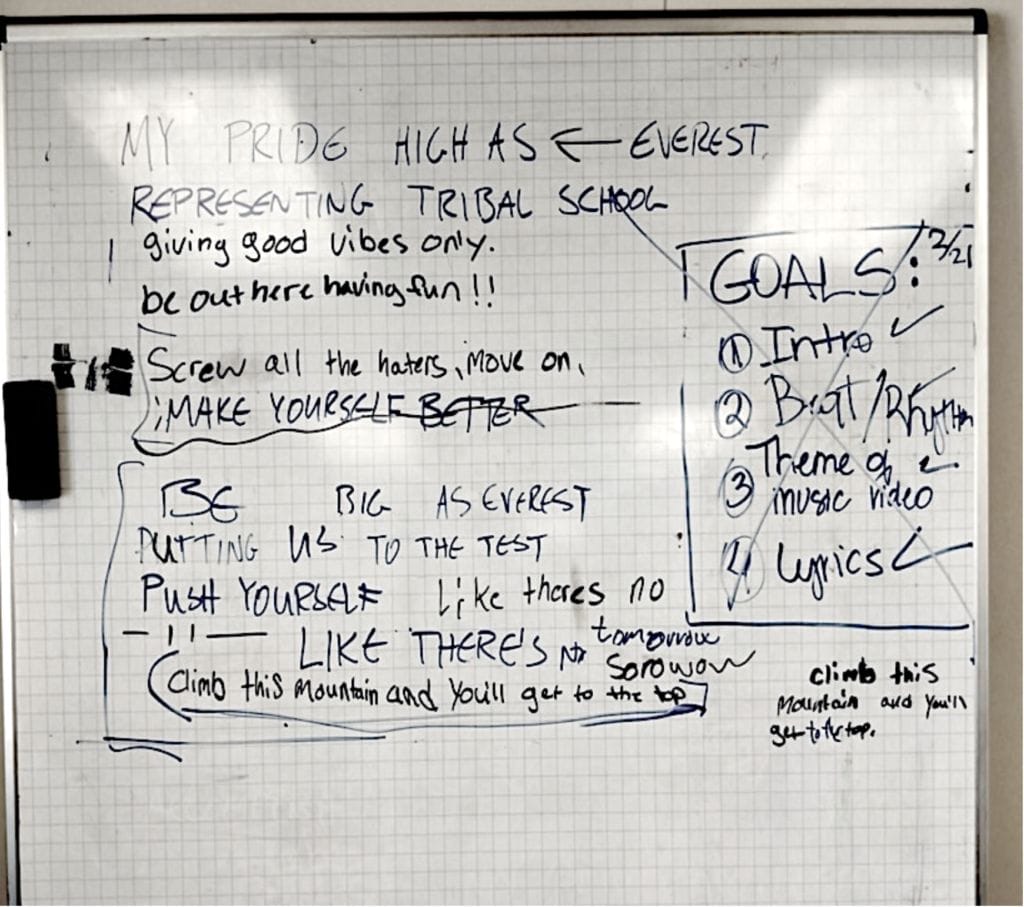

Making space for Indigenous ways of knowing in classroom music-making implicitly challenges longstanding educational hegemonies and should be critically considered by educators. From testimonio, tribal pride materializes at the epicenter of a newly emergent collective epistemology—a way of knowing birthed from the exchange of lived experiences. Students collaboratively craft scattered feelings into a draft of heartfelt phrases (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Students’ draft of heartfelt phrases.

The final three lines were students’ favorite of the day’s work session; they are a message of determination, resilience, and pride:

Push yourself like there’s no tomorrow

Like there’s no sorrow

Climb this mountain and you’ll get to the top

Testimonio was a way to engage in a pedagogical responsiveness that allows students to learn on their own terms and express their lived experiences as a collective, and as individuals. This project departed from conventional teacher training pedagogies. Process took precedence over product; emphasis on “authentic” replication of Western masters like Beethoven, Souza, or even Ellington, was discarded; and synthesis of tribal tradition and popular culture took center stage. In summation, in our experiences at YNTS, collective songwriting showed the capacity to promote equity and social justice through a pedagogical process that is inherently decolonizing, critical, and a strong step toward awakening American music education from the slumber of hegemony.

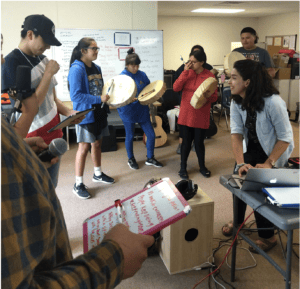

Figure 5. Students practice accompaniment for their collective lyrics.

Structures of Power and Imperialism: Mediating Tribal Education with State Demands

While testimonio and collective songwriting represent powerful tools for decolonizing work at YNTS, the tribal school does not exist separately from the structures of imperialism and power that have shaped the Yakama Nation’s borders. In fact, the school leadership team is continually mediating requirements of the settler-colonial state educational structures and their own interests in tribal culture sustainability through education in their school planning. Formerly controlled entirely by the Yakama Nation, the tribal school’s curriculum has included classes on tribal knowledge, such as Ichiskíin language, beadwork, and drumming. Alongside subjects like English, mathematics, and science, these classes on tribal heritage are supplemented by community involvement at the school and school events, such as opening and closing circles, champion sports programs, and family nights supported by Heritage University. However, the need for more funding and resources to attract and maintain teaching staff and create educational opportunities to allow students to compete with public school peers necessitates compromises between the bureaucratic demands of the state and the school’s tribal heritage education.

In a substantial meeting about our program and the school, Principal Adam Strom described how YNTS has recently become a state-tribal education compact school. As he explained it, this new hybrid structure has increased funding alongside the amount of formal expectations like testing, higher test scores, and increased attendance demands. Moreover, while YNTS has always endeavored to prepare students to compete academically with state public schools, this new affiliation affects the amount of time and emphasis they can give to classes focusing on tribal knowledge. As Smith (2012) states, “[structures of imperialism and power relations are] grounded in reproducing material realities and legitimating inequalities and marginality” (201). In essence, the additional funding that the state-tribal education compact provides does indeed create opportunities and resources that YNTS might not have otherwise have. However, the simultaneous increase in bureaucratic state educational demands that necessitates restructuring of YNTS curriculum to focus less on tribal cultural classes reinforces and maintains the hegemonic imperial codes that situate settler-colonial knowledges in positions of power over Indigenous heritage.

We saw this firsthand during the 2020 project. Many students were pulled out of collective songwriting sessions for formal testing of academic learning. The availability and use of the computer lab, which functioned simultaneously as a site for music production on GarageBand and as a state testing lab, required more strategic planning. At the same time, YNTS retains forms of tribal authority within this structure, and their focus on sustaining tribal knowledge was still seen and felt, mediating these new demands. For example, community-based, tribal activities were still encouraged, and students were allowed to opt into programs like ours as they wanted. This effectively excused them from their academic classes (with the exception of the testing pull-outs) to do projects like collective songwriting. One notable example was a male student who, after several informal chats with one of our team members in the hallway outside the computer lab, eventually opted into a beat-making session in the lab midday on our third visit. He subsequently returned for the full fourth session the next week. Thus, the tribal school’s continued support of such co-curricular decolonizing projects centering student-driven tribal issues represents an important corrective to increasing settler-colonial state structural demands, offering alternative structures that continue to support tribal cultural sustainability through education and the arts.

Figure 6. Poster at the YNTS entrance.

Reimagining the World through Music: Traditional and Contemporary Practices

In preparation for the 2018 revival of Music Alive! In the Yakima Valley, when the program came out of hiatus turned toward testimonio and collective songwriting, a grant provided instruments for digital music-making so students had contemporary tools for creative musical expression. The purpose was to create workstations where students could explore recording audio, MIDI-controlled software, and loop libraries, tools that lend themselves easily to popular music production. When ideas of pride were probed in our workshop discussions, questions of music of the Yakama were raised. We, the teaching team, had no prior experience with the music, thus it became essential to consult with culture bearers. In one case, the family of one of the YNTS teachers joined us with hand drums and shared songs, while in other cases students themselves led with songs they had acquired in pow-wows, family gatherings, and practice sessions. As students graciously shared their stories and their music, the roles of teacher/student flipped.

Valuing student agency and voice is at the core of the workshops, forming a collaborative environment in making music. Musically, the project is student-driven and therefore students’ musical identities are a subject of much of the conversation throughout the workshops. At the start of the workshops, we ask students to fill out a survey on their musical preferences that works as a place for students to report their favorite musical styles and artists. The process of musical compositions and production begins by exploring rhythmic and sonic properties of their favorite songs. Genres that fall under popular music (hip hop, pop, rock, country) are well represented and when Native heritage and pride enter the conversation, traditional music and language become topics. Addressing and exploring their identities through this process make for powerful moments.

During a lyric-making session, students worked in small groups using handheld whiteboards for writing the poetic lines they would invent. After sharing and reviewing the work by the entire group, some lyrics made it onto the bigger whiteboard where we worked out a poetic meter over a modern hip-hop beat. A small group of female students got together with their whiteboards and asked if they could leave the room to write a separate song using their lyrics: “Gotta keep this thing up called a strive / We never hide keep our pride / We’ll never die inside.” They wanted to meet with John Scabbyrobe, a teacher and musician at their school who teaches, among other subjects, drum classes using traditional hand drums. He is a well-respected musician in the community, a member of the Grammy-nominated Black Lodge Singers. The drum classes are all male at YNTS, a custom in Yakama drumming circles, as women stand in an outer circle, singing and drumming (Perea 2014). After getting a positive response from us, the group of girls went to Scabbyrobe’s classroom and asked for help using the hand drums and composing a melody for the lyrics they brought to him. After conferring with him, they returned with an original song, in traditional Yakama drumming and singing style, circumventing the popular music-making going on with the more outspoken student group. At the end of our workshops, during the final performance, Scabbyrobe joined the group of girls onstage, validating their efforts to seek a more traditional Yakama composition.

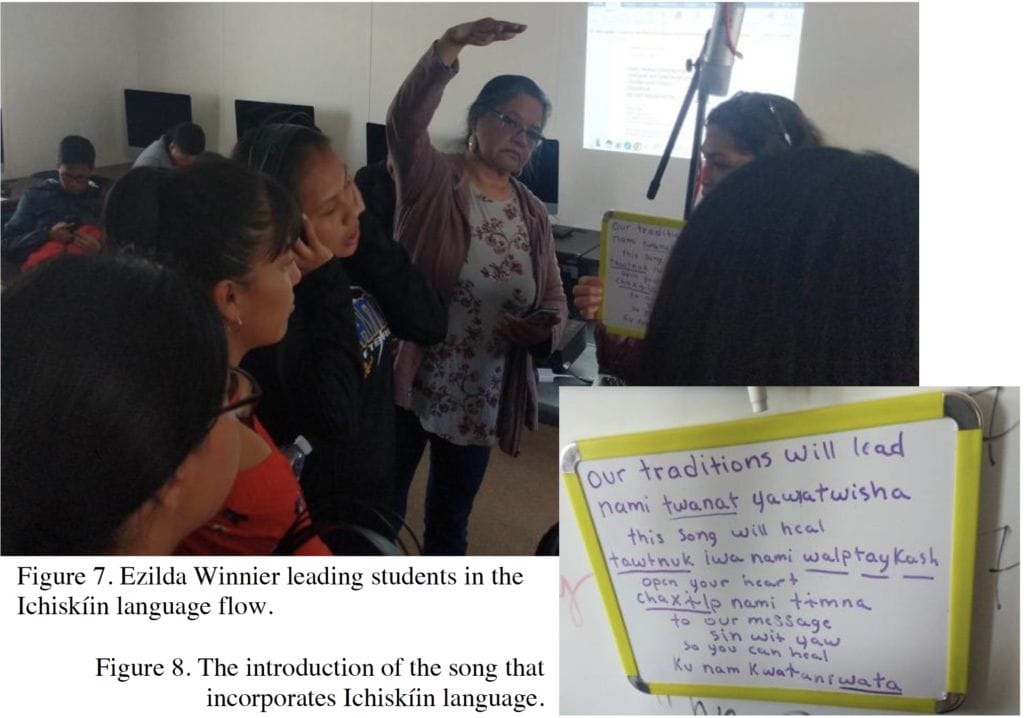

Other sessions included discussions about blending hand drums into the hip-hop production, resulting in hand drums pulsing through the whole track. Fitting their own Native musical heritage, the students reinforced their identity as Yakama, claiming their past heritage while reimagining what it can become. Elders involved in the process reported that songs had reached the tribal council (which was already supporting language revitalization efforts, one of which is a language app). As Ezilda recalled, the reaction was positive since the lyrics were meaningful for the students involved and also for the wider Yakama community (Figure 7).

“Gotta keep your culture up to stay alive”

This paper is a reflection on issues of equity and inclusion through testimonio and collective songwriting in a tribal school setting. It is the result of collaborative pedagogical design and delivery involving the university team of teachers with Native students, their teachers, and several community Elders. Situated alongside the efforts of the Yakama Nation to assert their identities, claim their sovereignty, and continue their decolonizing efforts, the students’ work acknowledges their relationships with people and their values and visions off the Reservation and around the globe. Throughout the years of the collective songwriting project, students’ compositions have expressed their multiple identities as Native youth in a globalized world dominated by popular culture and mediated by technology, as their songs blend drums of the Yakama tradition with software hip-hop beats, incorporating Ichiskíin language (Figure 8).

The “adults” of the project bring unique perspectives to the venture and its unfolding for the benefit of the adolescent students who fully deserve opportunities to explore and express their identities and interests musically and communally. Through this exchange, a process has evolved that allows blending and balances tools and techniques of school music pedagogy with Yakama cultural values and transmission practices. Highlights of the project were chronicled here with the intent of illustrating not just the project components but also the manner in which teaching toward equity requires sensitivity to the values and practices of students learning and living their Indigenous heritage while also responding to their place within the global youth community. Although the global outbreak of COVID-19 disrupted the final sessions and performances in 2020, YNTS students and teachers alike continue to text, talk, email, and use Google Classroom with the UW facilitators to share ideas and continue their music-making efforts. We all remain hopeful for the continuation of this project as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds.

With these stories, we have attempted to bring forward moments from a music education project that acknowledges commonplace settler-colonial structures while giving students the opportunity and space to exercise their agency to resist them. These narrative snippets are meant to inspire a new way of conceptualizing instruction by focusing on process over product and embracing a level of cultural responsiveness that leaves space for Indigenous ways of knowing and expressing. Decolonizing efforts also encompass a disruption of Eurocentric and federal and state pedagogies that may fall short in capturing the hearts and minds of students, especially Indigenous students mediating local and global youth identities. While we, as a singular team of state university activist-educators, are not in a place to disrupt larger imperial power structures within education in accordance with a framework of teaching for equity, we believe that our collaborative efforts with the Yakama Nation are an aspirational example of teaching toward equity. Through an exploration of these collaborative processes of Native student-driven music-making, we hope that others may find ways to tell their own stories as a means for teaching toward equity.

Kaity Cassio Igari is an MA student in Music Education at the University of Washington, with a research focus in Culturally Responsive Teaching and professional development.

Juliana Cantarelli Vita is a PhD candidate in Music Education (with emphasis in Ethnomusicology) at the University of Washington, with a research focus on children’s musical cultures and gender and music.

Jack Flesher is a PhD student in Ethnomusicology at the University of Washington, with additional graduate certificates in both Public Scholarship and Ethics.

Cameron Armstrong is an MA student in Music Education at the University of Washington, with a research focus in digital technologies and informal music learning.

Skúli Gestsson is a PhD candidate in Music Education at the University of Washington, with a research focus on creativity and popular music in education.

Patricia Shehan Campbell is professor of music (Music Education and Ethnomusicology) at the University of Washington, specializing in World Music Pedagogy and children’s musical cultures.

Endnotes

1 Consisting of 14 Confederated Tribes and Bands, the Yakama Nation has more than 10,000 enrolled members. Traditional lands originally included approximately 12 million acres in Eastern Washington and surrounding areas; an 1855 treaty with the Washington Territory governor established a 1.3 million-acre Yakama Nation Reservation near Toppenish, WA. The Nation retains hunting, fishing, and gathering rights and maintains a number of enterprises and community programs, including public and tribal schools. Language revitalization is of particular concern. Located in Yakima County, the Nation was especially hard hit by COVID-19 during the Spring 2020 outbreak, losing many Elders and community members.

2 The state education compact allows YNTS to replace “foreign language curricula” with Native language classes (Washington State Superintendent of Instruction-Yakama Nation 2019), so Elders Ezilda Winnier and “Tony” Washines coach students in the Ichishkíin dialect, part of the Sahaptin language family. Language classes emphasize vocabulary, syntax, and grammar as well as the Native epistemologies embedded in the language and its use. While students may not attain total fluency, they have the opportunity to be more connected to their culture and, sometimes, to speak Ichishkíin with grandparents and Elders. As of 2012, it was estimated only between 5 and 25 first-language speakers remained, all of whom were bilingual in English (Jansen 2012). Revitalization efforts also include a dictionary by Beavert and Hargus (2010), available via a website used by students at YNTS.

3 The issue of MMIW has plagued the Yakama Nation for over a century (Washines 2019). The local newspaper, the Yakima Herald-Republic, published a non-exhaustive list titled “Vanished” in 2020 of 37 MMIW on or around the Yakama Nation Reservation extending back to the 1980s. In 2018, the Yakama Nation formed an MMIW committee to begin address this longstanding issue formally and further gained support of U.S Senator Patty Murray (Petruzzelli 2019).

URLs

http://marthagonzalez.net/entre-mujeres

Works Cited

Baldy, Cutcha Risling and Melanie Yazzie. 2018. Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. 7.1:1-18.

Beavert, Virginia and Sharon Hargus. 2010. Ichishkíin Sínwit Yakama/Yakima Sahaptin Dictionary. Toppenish, WA, and Seattle: Heritage University and University of Washington Press, https://depts.washington.edu/sahaptin.

Bigelow, Bill, Brenda Harvey, Stan Karp, and Larry Miller, eds. 2001. Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol. 2: Teaching for Equity and Justice. Milwaukee: Rethinking Schools.

Campbell, Patricia Shehan, Christopher Mena, Skúli Gestsson, and William J. Coppola. 2019. “Atawit Nawa Wakishwit”: Collective Songwriting with Native American Youth. Journal of Popular Music Education. 3.1:11-28. doi.org/10.1386/jpme.3.1.11_1

Freire, Paulo. (1968) 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30thAnniversary ed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, Bloomsbury Publishing.

Gonzalez, Martha E. 2015. “Sobreviviendo”: Immigration Stories and Testimonio in Song. Diálogo. 18.2:131-38. doi.org/10.1353/dlg.2015.0027

Hill, Robert. 1892. Indian Citizenship. In Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction at the Nineteenth Annual Session Held in Denver, Col., June 23-29, 1892, ed. Isabel C. Barrows. Boston: Press of Geo H. Ellis, 34-44.

Jansen, Joanna. 2012. Ditransitive Alignment in Yakima Sahaptin. Linguistic Discovery. 10.3:37-54.

Lee, Tiffany S. and Teresa L. McCarty. 2017. Upholding Indigenous Education Sovereignty through Critical Culturally Sustaining/Revitalizing Pedagogy. In Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World, eds. Django Paris and H. Samy Alim. New York: Teachers College Press, 61-82.

Perea, John-Carlos. 2014. Intertribal Native American Music in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

Petruzzelli, Monica. 2019. Senator Meets with Yakama Nation Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Committee. YakTriNews, last updated Dec. 18, 2019, https://www.yaktrinews.com/senator-meets-with-yakama-nation-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women-committee.

Reyes, Katherine B. and Julia E. Curry Rodriguez. 2012. Testimonio: Origins, Terms, and Resources. Equity & Excellence in Education. 45.3:525-38.

Shipley, Lori. 2012. Musical Education of American Indians at Hampton Institute (1878-1923) and the Work of Natalie Curtis (1904-1921). Journal of Historical Research in Music Education 34.1:3-22. doi.org/10.1177/153660061203400102

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed. London: Zed Books.

State-Tribal Education Compact between the Washington State Superintendent of Public Instruction and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Washington State Superintendent of Instruction – Yakama Nation. March 6, 2019. Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/indianed/pubdocs/Yakama_Nation_State_Tribal_Education_Compact_%282019compliant%29.pdf.

Washines, Emily. 2019. MMIW: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIW, MMIWG). Native Friends, https://nativefriends.com/pages/mmiw.