Figure 1. An ofrenda created by local Latinx artists and educators for display at LASC in Lexington, Kentucky, 2015. Photograph by Ethan Sharp. Used by permission of LASC.

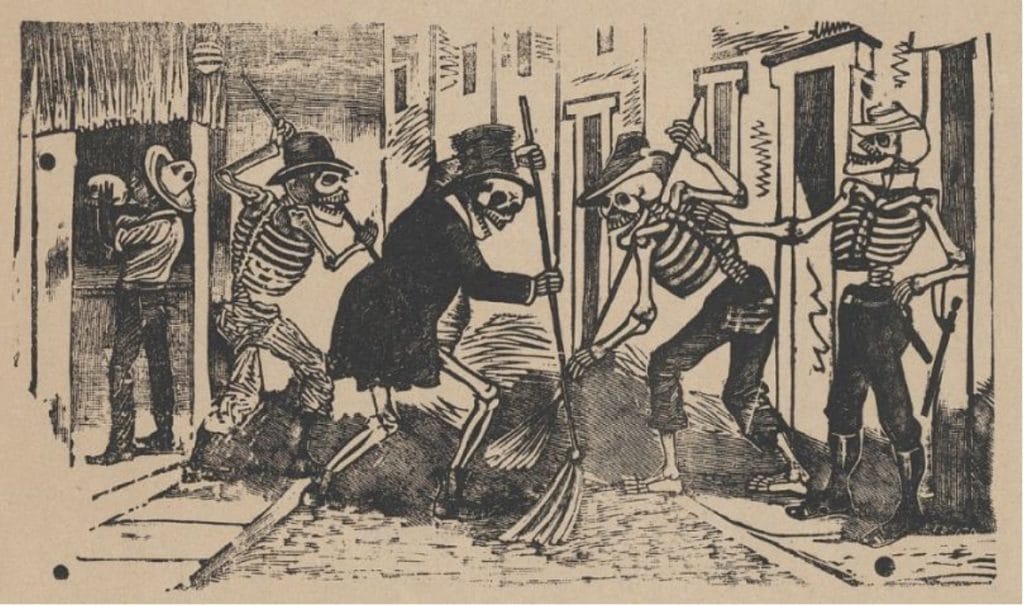

Beginning in the late 1800s and early 1900s, broadsheets by Mexican lithographer José Guadalupe Posada popularized the imagery of calaveras, in which skeletons dress and act as if they were living humans, often in scenes satirizing aspects of Mexican society. In turn, the imagery of calaveras intertwined with traditional and popular culture associated with el Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead (Pérez 2020). In the United States, however, Posada’s broadsides featuring poems of different lengths alongside his illustrations are not well known. The poems, referred to as calaveras literarias, or literary calaveras, are rooted in and blend oral and literary traditions. Many people in Mexico and Latinx artists in the U.S. continue to write and perform calaveras. Often, these verses make fun of living people by eulogizing them as if they have died, but the term calavera may apply to any verse about death or a person who has actually died.

As fascination with el Día de los Muertos has grown in the U.S., the number of arts organizations and museums organizing public events for it increases every year, and in many cases, organizations are more committed to providing an entertainment experience rather than educating audiences about a traditional ritual.1 Amid these developments, the practice of reading and writing literary calaveras can refocus attention on the deeper meanings, traditions, and creative possibilities of the festival. This article describes the collaboration of Carolina Quiroga, a Colombian-born professional storyteller, with Ashlee Collins, an arts educator at the Living Arts and Science Center (LASC) in Lexington, Kentucky, myself, and other members of LASC’s administrative team. Our project guided a diverse group of Title I middle-school students in one of LASC’s after-school programs through educational activities related to el Día de los Muertos in the fall of 2020. Because we launched the project during the Covid-19 pandemic, Carolina and Ashlee interacted with students in a virtual classroom on Zoom. We were surprised that one of the most successful activities was a lesson that introduced students to the poetry of calaveras and involved the students in writing their own.

Drawing on observations of the after-school activities and interviews with Carolina and Ashlee, this article addresses how the project originated, what we learned from it, and how it can inspire further study and use of calaveras in museum educational programs. We believe that programs involving calaveras can enrich the experience of el Día de los Muertos by inspiring different forms of vernacular creativity, providing more occasions for reflection, and building relationships between museum educators, students, and local communities.

Figure 2. Performers of Mexican folklórico dance pose at LASC’s annual celebration of el Día de los Muertos in Lexington, Kentucky, 2017. Photograph by James Shambhu. Used by permission of LASC.

El Día de los Muertos in Lexington, Kentucky

In the 1970s, Chicanx artists and activists began organizing events for el Día de los Muertos in public venues in the U.S. (Marchi 2009, 47). These events typically involved re-creations of ofrendas, the colorful, multilayered altars that Mexicans and Mexican Americans traditionally create to remember and commune with deceased loved ones as both political and artistic expressions. By the 1990s, the festival moved beyond Chicanx spaces, as arts organizations and museums across the U.S. began organizing displays of ofrendas and related programs for largely white audiences (Davis-Undiano 2017, 138). In addition, K–12 educators began introducing students to el Día de los Muertos and in the process contributed to an erasure of the religious and traditional significance of the festival. This growth in popularity coincided with an increase in the 1990s of immigrants from Mexico settling in new destinations with relatively small Latinx populations, like Lexington, Kentucky. Some motivations behind cultural organizations’ involvement in el Día de los Muertos have been to engage new and growing Latinx communities. Unfortunately, organizations do not always make a deep commitment to collaborate with Latinx communities, research the festival’s traditions and meanings, or honor the festival’s importance to traditional practitioners (Gwyneira, Bojorquez, and Nichols 2012).

Founded in 1968 in one of Lexington’s lowest-income neighborhoods, LASC functions as an arts organization and science center. In the 2000s, LASC staff began el Día de los Muertos activities, and by the 2010s, LASC’s celebration was the organization’s largest, best-known annual event. It drew thousands of participants from across Central Kentucky, and featured a variety of ofrendas created by community groups, including Latinx university and high school student organizations, local artist groups, and teacher-led elementary and middle school groups (Figure 1). LASC staff, largely white with no Latinx members, was concerned with ensuring that the growing number of Mexican immigrants in Lexington recognized the celebration as authentic and worked closely with artists and educators of Mexican descent in planning the event. For example, LASC always held the celebration November 1, regardless of the day of the week on which it fell; offered a variety of activities leading up to and in preparation for the event, such as making sugar skulls; and used a nearby historic cemetery to display community ofrendas. In the 2010s, LASC staff began collaborating with the Casa de la Cultura KY, a nonprofit run by Mexican immigrants, to offer educational programs primarily for immigrants and their children, and Casa de la Cultura KY added folklórico dance and mariachi performances to the celebration (Figure 2).

While LASC has remained committed to collaboration, it has generated a more frenetic festival atmosphere of displays, activities, performances, and foods, with limited possibilities for dialogue within the celebration or the development of new educational programs about the traditions and innovations that animate the festival. In my role as grant program manager for LASC, I interviewed a small but diverse selection of people involved in creating ofrendas for the 2019 celebration and explored with them ideas for additions and changes. I found support for incorporating more opportunities to share stories and educational programs that featured Latinx artists and appealed to Latinx students.

One person clearly illustrated the potential of storytelling within the celebration. Milton Mezas, a young Latino activist, created an ofrenda with Kentucky Dream Coalition high-school students dedicated to advocating for immigrants’ rights. Milton explained that they dedicated their ofrenda to their grandparents, because “for a lot of undocumented immigrants, when loved ones die, they can’t go back to see them. That was the case for my mom…. The altar was for the loved ones who died and the people who don’t have the ability to go back to visit them.” In the process of creating the ofrenda, which featured photographs, foods, and other items associated with their grandparents, they shared stories among themselves. Once the ofrenda was on display, they shared their stories with visitors to LASC. Milton was impressed with their receptivity and remembered a woman responding, “Wow, I didn’t realize that this was an actual reality.”

Based on my interviews with Milton and others, I collaborated with LASC staff on a proposal to bring to Lexington a Latinx storyteller who could facilitate storytelling and dialogue during el Día de los Muertos. We reached out to Carolina for help. She was born and spent much of her early life in Cali, Colombia. Inspired by the stories of her mother, Carolina took up storytelling as a hobby and at age 30 moved to Tennessee to study for a master’s in storytelling at East Tennessee State University. After earning her degree, she started a career as a professional storyteller and educator specializing in traditional Latin American stories. Carolina explained her interest in traditional stories: “They teach us creative ways to approach things and critical thinking…I wanted to just do traditional stories because I believe that there is so much potential for education, for connection, and even for transforming those stories into your own personal story.”

In 2014, Carolina moved with her husband to San Antonio, Texas, where she facilitated an education program for Say Sí, an arts and youth development organization. Carolina led ten Saturday workshops for middle-school students, culminating in an event with Carolina and students sharing stories about death and loved ones who had died. This coincided with Say Sí’s popular annual celebration of el Día de los Muertos. Although Carolina did not grow up celebrating el Día de los Muertos as it is often celebrated in Mexico or Latinx communities in the U.S., she had been telling traditional stories related to el Día de los Muertos and was eager to find a way to contribute to the festival. We believed that Carolina could provide an impetus for changes in LASC’s festival. She could engage English- and Spanish-speaking audiences and had ties to the Southeast, and because of her experience in San Antonio, she recognized a need to slow down activities surrounding el Día de los Muertos and shared our vision of creating opportunities for sharing and learning about the festival’s rich traditions. Carolina observed:

El Día de los Muertos is very huge in San Antonio; there’s the decorations and the music and the food, of course, but the whole celebration didn’t seem to have a storytelling component. It was missing the reflection. You’re either working putting an altar together, or you have to put a lot of work into cooking. And if you’re not the one putting the stuff together, you are the one attending it, and if you’re attending it, you just come in, take pictures, look a little bit here and there, and then you’re out.

Transitions to Virtual Programs

In 2020, with support of the Casa de la Cultura KY, LASC received an NEA Folk and Traditional Arts grant that included funds to bring Carolina to LASC for a week-long residency. The proposal was that her residency would occur a few weeks before el Día de los Muertos, and she would facilitate a workshop to prepare students and community members to share stories about ofrendas. Because of the pandemic and the closing of LASC to the public and cancellation of events, not until summer could staff reorganize and begin planning fall programs.

One educational program that LASC staff was committed to providing, by adapting it to a virtual format, was an after-school program for students enrolled in the Lexington Traditional Magnet School (LTMS), a nearby Title I middle school. Despite its name, only a small percentage of LTMS students are enrolled in the magnet program, and the school draws most students from the surrounding neighborhood. The after-school program provides enrichment through interactive 90-minute sessions three times a week. From 2018 through early 2020, an average of 20 students attended each session and established good rapport with Ashlee. Ashlee explained: “The students that come are from this neighborhood. A lot of the times we see them walking home after school. The majority are on the free and reduced lunch program. [They’re from] multigenerational homes, a lot of times, night-working parents.” Most are African American, and there is a growing number of Latinx students.

As she was working on the fall schedule for the LTMS after-school program, Ashlee met with Carolina, and Carolina agreed to collaborate with Ashlee and her students via Zoom on el Día de los Muertos activities. In addition, Carolina created three 30-minute videos that LASC staff shared on its website and social media channels. In each, Carolina describes an aspect of el Día de los Muertos, tells a story, and guides viewers through a simple activity. In one video, for example, she demonstrates how to make cempasúchil flowers with tissue paper. Carolina speaks primarily in English in the videos, but they incorporate Spanish subtitles. To facilitate virtual engagement with the festival, LASC staff created and shared a short video that documented diverse community members creating ofrendas in LASC’s gallery and telling what the festival means to them.

As a specialist in theatre arts, Ashlee explored different forms of storytelling in the LTMS after-school program in the fall. She originally planned to have Carolina lead workshops culminating in a virtual storytelling event but realized this plan would not work. “As the semester went on, we learned that teaching virtually was more difficult than we anticipated for different reasons. Students had been online for many hours because schools had not returned to in-person instruction.” She found many live in multigenerational homes, with younger siblings and cousins, and felt uncomfortable turning on their cameras and microphones for virtual sessions. Only four or five students actively participated in each session, and those who participated were not the same from week to week. So, Carolina and Ashlee adjusted their plans to offer one-off lessons, concluding with a lesson on literary calaveras.

Figure 3. Carolina and Ashlee introducing José Guadalupe Posada’s illustrations in the LASC virtual classroom, 2020. Photograph by Ethan Sharp. Used by permission of LASC.

This lesson began with Ashlee displaying the texts of short calaveras on the Zoom screen and Carolina and Ashlee taking turns reading each aloud. Then Ashlee displayed examples of Posada’s illustrations, and they guided students in examining scenes with skeletons dressed in the style of Posada’s era (Figure 3). Asking, “What are some of the little things we see? How do they tie humor into Day of the Dead?” they gave students five minutes to write a verse about the scene. Students shared their verses in the chat box.

Carolina and Ashlee were surprised at how well the lesson went. Ashlee commented, “We didn’t plan to spend too much time on the calaveras. We were going to introduce them and how they play into Day of the Dead, but they got into it, so we just played with what they were interested in.” Although the virtual format limited activities, it was ideally suited to keeping students engaged throughout the lesson on literary calaveras and allowing them to experience the accomplishment of quickly writing and sharing verses. Students focused together on a series of images on the screen and interacted in the chat box, making it easier for students who did not turn on their cameras and microphones to participate. As students commented on Posada’s illustrations and shared verses in the chat box, Carolina and Ashlee offered commentary and clarified comments and ideas.

A Closer Examination of Calaveras

When we were exploring ideas for deepening the celebration of el Día de los Muertos in 2019, we had not considered literary calaveras as a potential element, but observing Carolina and Ashlee’s lesson, we found that the poetry of calaveras holds advantages over other forms of narrative expressions that we sought to promote. The practice of writing verses about death, the dead, and living people and things as if they had died was common before Posada began printing his broadsides, and it has developed over many years and connects with several important aspects of el Día de los Muertos. Carolina noted:

[Writing] calaveras with the kids… that was new to me. I hadn’t done it before. Once I began performing in San Antonio, people began telling me about the literary calaveras and how they would do it in Mexico. I came in contact with this amazing book [Digging the Days of the Dead by Juanita Garciagodoy] and [learned more about the] calavera writing contests in schools in Mexico. At the same time, I didn’t know how to approach it because some of those calavera contests, they write about someone that is alive, but as if they had passed. And here in the U.S., when you bring up the concept of death, and then when you’re trying to make fun of that or talk about that person that is in front of you as if they were dead, people might take it as an insult or will not take it lightly. I was like, “How can I work around this in a way that no one feels threatened?” So, I think there is still work to do on this. There’s so much potential [with literary calaveras].

Anthropologist Stanley Brandes notes that calaveras may have originated with pasquines, the “mocking verses scrawled on walls to which passing readers added their own lines,” from earlier centuries (Brandes 2006, 116). However, it seems more likely that the practice of writing calaveras was initially inspired by and drew on material from oral tradition, and the practice continued to develop in the 20th century as it intertwined with other traditions of el Día de los Muertos. These traditions included writing and reciting calaveras in honor of friends or family members in private settings (Brandes 2006, 116), inscribing brief verses on sugar skulls given to friends and family members (Carmichael and Sayer 1992, 115), and writing and displaying the text of a calavera in an ofrenda (Garciagodoy 1998, 288).2 Across the different contexts in which it appears, the poetry of calaveras expresses a playful approach to death and life and is often a vehicle of social criticism.

By reading examples of calaveras at the beginning of the lesson, Carolina and Ashlee introduced students to some of the common themes of calaveras, the tone they usually employ, and the ways they comment on relationships and society. By reading short calaveras and calaveras with a simple rhyming scheme or an open form, they also showed students how they could easily write calaveras. The first example was a translation of a traditional Mexican children’s verse. Although it does not address or reference a living or dead person, it personifies death as the skeleton of a poor woman and pokes fun at death, exhibiting playfulness and social criticism.

Dry death

was sitting on a dump

eating hard tortillas

to see if she could grow plump.

Dry death

was sitting among the reeds

eating hard tortillas

and unsalted little beans. (Garciagodoy 1998, 233)

The last example was addressed to a young person who died, in the voice of a friend.

Angel, when you come back

I bet you’ll come back on your black cruiser

moving slowly with a lit sweet swisher cigar in your mouth

you’ll be wearing a black buttoned up shirt with a collar

But only buttoned up halfway

and baggy jeans

and your iPod will be playing Tupac loud enough so everyone can hear.

When you come back, Angel

me you and Hans will skate together out at UCSB

and maybe the skate park.

We’ll just ride around

you’ll say “Whas up den?”

and I’ll tell you

we are good friends

like I meant to do

I guess I did

when you were here. (Latin American and Iberian Institute, N.D., 32)3

This example, which uses an open or free-verse form relatively easy to replicate, illustrates the conjuring power of the language of calaveras to bridge the divide between the dead and the living and create a figurative space in which the dead and the living can commune. This power complements the work done through ofrendas and traditional celebrations for el Día de los Muertos, which help to maintain and strengthen relationships among the living, as they reestablish connections between the dead and the living. As Carolina shared:

Just as I am somewhat interpreting el Día de los Muertos for other people, for the audience, that does not mean that [what I say] is exactly how every person in Mexico will practice el Día de los Muertos. In the end, I think the message that goes through the whole thing is just how to honor your ancestors. You honor them when you welcome them with a fiesta, you remember them. And how do you remember them? Through their things, things that they love to wear, through the things that they love to eat, through the flowers, through the stories, through the pictures.

By moving from reading examples to examining Posada’s images, Carolina and Ashlee continued to emphasize the role of humor, ensuring students incorporated humor into their verses. Although the illustrations were in black and white and the original messages were largely lost on students, they provided ample material for students to comment on as they were writing their verses. For example, in response to Posada’s illustration of La Adelita or La Soldadera, the woman on horseback with a whip, which the students are examining in Figure 3, one student wrote the following and posted it in the chat box:

Kissing Kate never stopped

Fighting off bandits with her whip that pops!

The thieves fled because of the dead

and never came back up top

La Adelita is a representation of the women soldiers who fought in the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920 and helped topple a dictator. In response to a scene in which skeletons are sweeping the street, likely after a major festival, and a skeleton dressed as a police officer directs the street sweepers (Figure 4), one student wrote:

The road was paved

With dirt and dust

Tommy decided that

Staying clean was a must.

He told his friends

You see…I broke my wrist

In a past life

And never learned to sweep

Thanks to my loving wife.

Figure 4. Broadsheet featuring street sweepers by Posada, N.D. Public Domain.

In this scene, a form of social criticism is at work because Posada is depicting the figures playing different roles, with different statuses, while continuing to poke fun and insist that all people are basically skeletons. As the literary scholar Juanita Garciagodoy notes, the imagery of calaveras generally carries a critique of hierarchies and capitalist systems (1998, 204, 272). It was not necessary for Carolina and Ashlee to bring up these details, but the student homed in on why one figure in the scene is not sweeping and others are sweeping. The student’s verse suggests that there is potential in exploring with students how both visual and literary calaveras question social structures and expose corruption and injustice.

Conclusion

During the Covid-19 pandemic, educators around the world had to adapt their lesson plans for Zoom and struggled with engaging students and facilitating dialogue and collaboration in a virtual classroom environment. Educators who were primarily working for or with arts organizations and museums faced the additional challenges of rebuilding educational programs amid the loss of revenue, steep cuts in staff, and an uncertain future, which required educators to acquire new knowledge and skills and be innovative. At LASC, Ashlee and other staff members built on LASC’s practice of collaborating with community members and expanding programs about el Día de los Muertos by working with Carolina and offering virtual programs that explored underappreciated aspects of the festival. Carolina and Ashlee re-centered their approaches and began to address the problem of superficial engagement with the festival. Ashlee summarized: “I think with [el Día de los Muertos] in years past, it is such a huge range of people with a huge range of knowledge coming in that we kind of have to cater to people who don’t know much and give them a taste of the culture, but this really let us dive in to the history and how it has evolved over the years, and how it became more popular.”

In the process of making virtual programs as engaging and as effective as possible, we discovered literary calaveras. Our experience is limited, but the study and writing of calaveras in educational programs in the U.S. is relatively uncharted territory. I have found only one article that describes an example (Leija 2020), so we offer here what we have learned. We hope that our project will encourage experimentation with writing and performing calaveras and serve as a point of reference for additional innovations in museum educational programs and greater reflection about el Día de los Muertos.

In sum, amid the challenging circumstances of the pandemic, we found that students were remarkably adept at writing calaveras and calaveras can provide valuable new perspectives on the imagery, humor, and meanings of traditions surrounding el Día de los Muertos.4 LASC staff and Carolina plan to continue collaborating and involve more students in studying Posada’s illustrations and writing calaveras in their work. Carolina and Ashlee’s collaboration and the students’ calaveras demonstrate creativity and offer valuable lessons that will bring greater opportunities for dialogue, improvements in representation, and a deeper appreciation of the diversity of practices and beliefs surrounding death in the Americas.

Ethan Sharp is an independent folklorist and freelance grant writer in Lexington, Kentucky. From 2017 to 2020, he contributed to the expansion of programs for K–12 students and families as the grant program manager at the Living Arts and Science Center. In 2020, with an Archie Green fellowship from the American Folklife Center, he began documenting the growth of the peer support profession in response to the opioid epidemic in Central and Eastern Kentucky. Ethan holds a PhD in Folklore and an MA in Latin American and Caribbean Studies from Indiana University.

Endnotes

1 In Mexican cities and sites that attract many tourists, el Día de los Muertos has similarly become an occasion for spectacle and entertainment. The Mexican popular culture critic Néstor García Canclini describes the festival in touristy Janitzio in the State of Michoacán as a “giant make-believe” experience (García Canclini 2010, 96).

2 There may also be linkages between writing and performing literary calaveras and other forms of improvised oral poetry in Latin America, such as the décima (Armistead 2003) or the verses employed in musical duels in huapango arribeño (Chávez 2017).

3 This example originally appeared in educational materials compiled by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and was reprinted by the University of New Mexico Latin American and Iberian Institute with permission from the museum.

4 Students who participated in the calavera writing exercises were a mix of African American, Latinx, and white students. As one of the anonymous reviewers for this article pointed out, students’ familiarity with hip hop may have been a factor in their composing calaveras so quickly since hip hop often improvises verses that use rhythm and rhyme in complex ways.

Works Cited

Armistead, Samuel. 2003. Pan Hispanic Oral Tradition. Oral Tradition. 18.2:154–56.

Brandes, Stanley. 2006. Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: Celebrations of Death in Mexico and Beyond. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Carmichael, Elizabeth and Chloe Sayer. 1992. Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Chávez, Alex E. 2017. Sounds of Crossing: Music, Migration, and the Aural Poetics of Huapango Arribeño. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Davis-Undiano, Robert Con. 2017. Mestizos Come Home! Making and Claiming Mexican-American Identity. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

García Canclini, Nestor. 2010. Transforming Modernity: Popular Culture in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Garciagodoy, Juanita. 1998. Digging the Days of the Dead: A Reading of Mexico’s Days of the Dead. Niwot: University Press of Colorado.

Gwyneira, Isaac, April Bojorquez, and Catherine Nichols. 2012. Dying to Be Represented: Museums and Día de los Muertos Collaborations. Collaborative Anthropologies. 5:28–63.

Latin American and Iberian Institute. N.D. Día de los Muertos K-12 Education Guide. Albuquerque: Latin American and Iberian Institute, University of New Mexico.

Leija, María G. 2020. Día de los Muertos: Opportunities to Foster Writing and Reflect Students’ Cultural Practices. The Reading Teacher. 73.4: 543–48.

Marchi, Regina. 2009. Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Pérez, Laura. 2020. Fashioning Decolonial Optics: Days of the Dead Walking Altars and Calavera Fashion Shows in Latina/o Los Angeles. In MeXicana Fashions: Politics, Self-Adornment, and Identity Construction, eds. Aída Hurtado and Norma Cantú. Austin: University of Texas Press, 191–215.