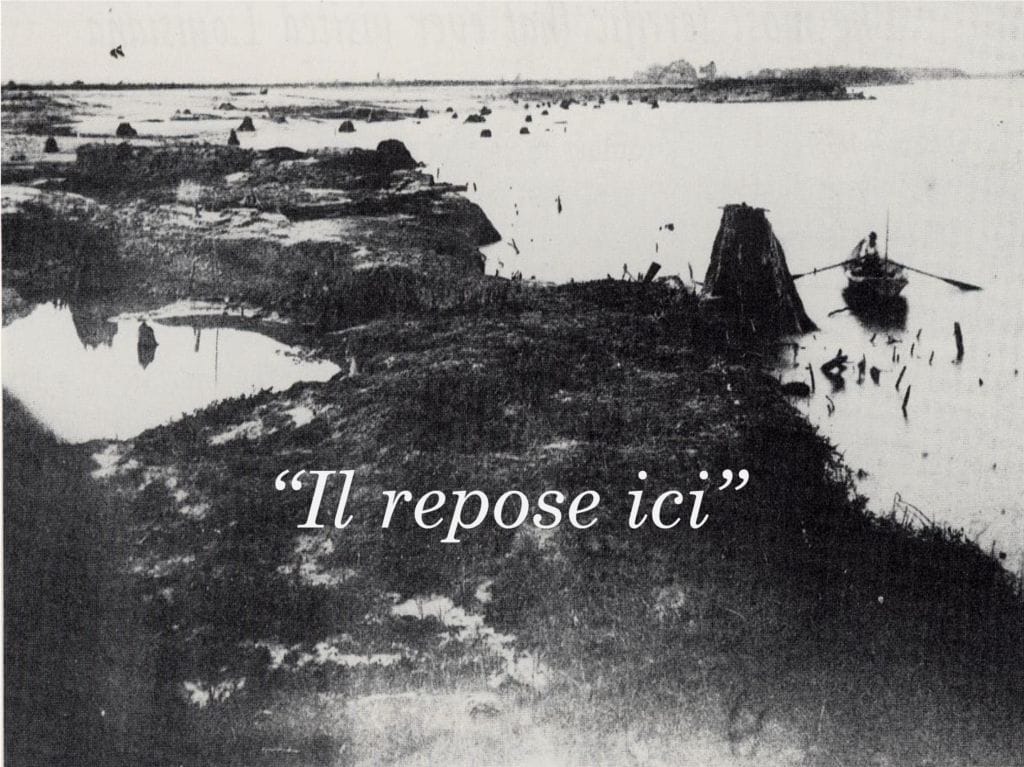

The coastline near Chêniѐre Caminada after the October 1 landfall of the Great October Storm of 1893, showing unearthed remnants of downed oak trees. Photograph by Mark Forrest (1894). Courtesy Cheniere Hurricane Centennial Collection.

The Great October Storm of 1893, despite remaining one of the largest natural disasters in the U.S. to date, was lost to history for nearly 100 years. It remained untold in hurricane treatises and in general literature and lingered only in the colloquial memory of coastal communities in southeastern Louisiana, scattered sparsely among descendant families of survivors no more than one generation removed from it. It was spoken of rarely in the communities settled in its aftermath and then only in hushed, remorseful tones. With the 1993 efforts of a visionary, grassroots organization committed to community education, however, this tragic event was raised to its rightful place in recorded history and common remembrance. Here, from the perspective of a 30-year legacy, we share our experiences producing lasting community learning through re-creations of historical folklife centered on a natural disaster.

Historical Setting

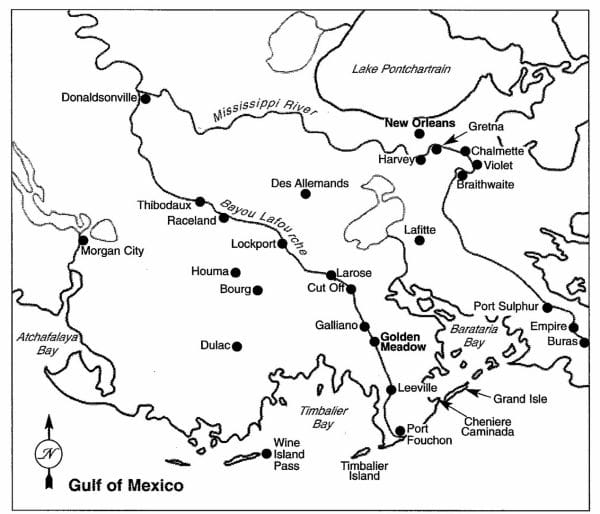

The Gulf Coast of Louisiana in the 19th century supported a number of fishing villages notable for providing a market living to fishermen, shrimpers, and oystermen as well as an abundance of fresh and dried seafood for subsistence. The largest, Chêniѐre Caminada, was built atop a plain of prehistoric beachheads (“chêniѐres”) formed over past millennia from river sediments driven westward by longshore currents. These sequential beachheads formed a peninsula, accreting to a point that rose as high as six feet above sea level, sufficient to support a grove of saltwater oaks, wooden houses, and a fishing fleet. At high tide, Chêniѐre Caminada was essentially an island, part of the barrier island complex west of the river across southeastern coastal Louisiana, with a saltwater fishery to the south and brackish fishery to the north surrounded by marshland. On the Gulf of Mexico, at the southernmost border of Lafourche and Jefferson Parishes, the village became the major supplier of fresh seafood to restaurants and markets in New Orleans, about 50 miles sailing distance due north through Barataria Bay and bayous draining into it (Looper et al. 1993).

Map of southeastern Louisiana, including places mentioned in this article. Illustration reprinted from Falgoux (2017), with permission.

With an 1893 population of about 1,600, this multicultural but largely French-speaking wetlands settlement was formed by immigration of families of diverse nationalities interested in plying the rich fisheries of its unique position on the Gulf of Mexico. The population had doubled since the 1850 U.S. Census, creating a multigenerational settlement of mostly fishermen and their extended families (Pitre 1996). Fishing made Chêniѐre Caminada well-known on the Gulf as well as in villages and cities to the north, thanks in part to visiting contemporary writers. Kate Chopin, for instance, used the village as the setting for her 1894 short story “At Chêniѐre Caminada” and a scene in her 1899 novel, The Awakening, set in 1892.

Overnight, between October 1 and 2, 1893, a strong, rapidly moving hurricane crossed the Louisiana coastline without forewarning. The bustling community of Chêniѐre Caminada lay directly beneath its gyre and tidal surge. Front-page headlines of the October 4, 1893, edition of the New Orleans Times-Democrat called it “The Wind of Death.” The next day, headlines read “Two Thousand Dead” and “The Settlement of Chêniѐre Caminada Swept Out of Existence.” A contemporary poem by Jean Henriot1 describes the aftermath:

Au lever du jour l’eau complѐtement retirée

Nous laissait des cadavres, noyés, mutilés, massacrés,

Les maisons démolies, culbuttées, c’est la ruine complѐte.

Les survivants n’ont plus rien, plus de butin,…

*

At the break of day, the water, completely drawn back,

Left bodies for us, drowned, mutilated, massacred,

The houses demolished, knocked down, it is total ruin.

The survivors have nothing more, no more possessions,…

The Great October Storm of 1893 is colloquially known as the Chêniѐre Hurricane. Forensic analysis described the storm as follows:

The hurricane produced inundation, being the most severe in history, [reported] to have engulfed everything before it, and caused a loss of life estimated at 2,000 persons. On Chêniѐre Caminada, adjacent to Grand Isle, 1,150 persons perished, and on Grand Isle 18 died. Immense destruction of shipping and property was caused and the damage amounted to millions of dollars. (History 1972)2

The storm destroyed most weather instruments in its path, leaving an incomplete record of winds and rain at landfall. Modern estimates describe it as a Category 4 hurricane. It battered Chêniѐre Caminada for 10 hours before landfall, when it reached maximum winds of 130 to 140 mph and carried a 16-foot tidal surge across the Louisiana Gulf Coast (1893 Chêniѐre 2022).

The cemetery at Chêniѐre Caminada after landfall of the Great October Storm of 1893, showing fresh burials. Photograph by Mark Forrest (1894). Courtesy Cheniere Hurricane Centennial Collection.

Death, Loss, and Lore

By morning on October 2, 1893, survivors witnessed a gouged and barren beach3 with debris and bodies washing ashore. Of 300 homes, one remained standing. The entire fishing fleet had been demolished. Nearly half the women and children had perished. Family surnames became extinct overnight. In ensuing days, survivors struggled to bury the dead in the village cemetery, and a suspected mass grave was created to the immediate west of the cemetery property (Looper et al. 1993).4

With losses of homes, boats, and other means of subsistence, together with the burden of memory, many survivors never returned.5 Some families purchased property upland in the Lafourche and Barataria Basins. The displaced population helped found the Lafourche Parish villages of Leeville, Golden Meadow, and Côte Blanche, as well as the village of Westwego in Jefferson Parish.6

Beyond post-storm burials and family relocations, several stories related to the storm and its aftermath have survived as lore through the oral tradition. Modern authors Perrin (1977) and Rogers (1985) have captured some of the more persistent tales of Chêniѐre folklore. One prevalent story involves the chêniѐre’s indigenous oak trees. As a ridge of high land relative to surrounding marshland and water, chêniѐres support the growth of live oaks in dense, linear groves.7 Historical photographs agree with lore involving the topological bareness of the 1893 Chêniѐre Caminada peninsula.8 Oral tradition tells us that the Chêniѐre villagers systematically cut down their oaks and destroyed the indigenous grove so that sailing visitors and fishermen could more readily see and find their homes from a distance while sailing on the Gulf or on the back bay.9 Villagers are thus blamed for community mortality by their contemporaries for having destroyed the natural arboreous protection from storm winds.

In addition to being subjected to criticism for destroying their oak grove, villagers also suffered other historical blame for their demise. Surviving opinions of the Chêniѐre Caminada villagers referred to them as lazy, unindustrious, and indulgent, engaging in such pastimes as card playing and dancing.10 There is a pervasiveness in multiple stories handed down claiming that villagers were responsible for their mortality during the storm, which led at least one Perrin (1977) informant to report that “God didn’t like us.”

Another story cycle involves the church at Chêniѐre Caminada and its bell. These stories are supported by oral tradition and first-person written narratives left by Father Ferdinand Grimeau,11 pastor of Notre Dame de Lourdes Catholic Church on 1893 Chêniѐre Caminada. Notre Dame, used as a setting in Chopin’s fiction, was home to a tower bell that according to legend was forged from 700 pounds of silver, including pieces of pirate treasure.12 The silver bell produced a peculiar pitch and peal, commonly described as “a high, hollow ping” and “a mother wailing.” During the storm, the bell rang relentlessly in the darkness, buffeted by hurricane winds. According to tradition, it has been described as the most memorable experience of the great storm, a sorrowful, sickening symbol of the night of terror and destruction. Father Grimeau was traumatized by the continuous pealing, as he sought safety inside the church rectory during the storm.13 Survivors often spoke about the bell’s incessant clanging, and when it went silent on the morning of October 2 they knew the church had been destroyed. The bell was recovered in the aftermath, but, according to lore, disappeared after some time. One story has it discovered in 1918 some 50 miles away in the cemetery at Westwego, one of the villages founded by storm survivors. Eventually, the bell was returned to the Gulf Coast and now serves Our Lady of the Isle church in nearby Grand Isle, LA (Rouse 1979).

Remembrance

Chopin wrote her 1894 short story “At Chêniѐre Caminada” soon after news of the great storm hit national newspapers. Chopin and her use of the church in her 1899 novel The Awakening commemorated the village she knew and admired from her summer vacationing on Grand Isle. Other authors wrote of historical Chêniѐre Caminada following the Great Storm but most published in 1893 or a few years afterward.14 For nearly a century, there is a distinct paucity of writings on and references to the Great October Storm outside occasional periodicals published in New Orleans and locally—and then on only major anniversaries of the storm.

For first-generation survivors, however, the storm was not lost to history. The adage “Wounds cut into sand are healed by morning” applied neither physically nor psychologically. Every person displaced to post-storm communities in 1893 inevitably lost someone they knew, and such grief was no doubt more severe in those families who assumed care of orphans or the homeless following the storm. There was a collective grief among the communities formed after the storm that remained intense in the years following, and that intensity may have contributed to keeping remembrance and discussion hushed.15

In Chopin’s time, summer vacationers would travel by boat through Barataria Bay to arrive at beach resorts on Grand Isle. When a state highway was established south to the coast and then east to Grand Isle in the 1920s,16 however, weekend vacationing for many locals became common. The site of historic Chêniѐre Caminada was (and remains) traversed on each highway trip to and from the public beach on Grand Isle. The authors (JPD and WC) recall such sojourns as children in the 1960s and 70s, when the once bustling Chêniѐre land was mostly barren, home to sparse fishing camps and docks for small, private fishing vessels. To children, such trips seemed shrouded in mystery concerning the significance of place and our family history. This mysteriousness, the lack of a modern community, the sparse dwellings raised on pilings often showing scars from storms, and the pervasive odor of lingering seafood residue rendered a strong negative connotation when hearing the French word “chêniѐre.” Crossing Chêniѐre Caminada along the highway in the family car, parents would often slow down, make the sign of the cross, murmur a brief prayer, and stare with curiosity, perhaps as homage to the drowned dead or perhaps trying to bring themselves to understand such a large disaster and tragedy. But they spoke in hushed tones without detail or explanation, perhaps avoiding thoughts about the tragedy or perhaps hoping to return home across that site before dark to avoid hauntings for disturbing the dead or experiencing frightful feux follets.17

Stories of the storm that persisted to the time of the efforts of Perrin and Rogers were carried by oral tradition, but that transmission typically remained within families rather than across the community. And in later gener-ations, the storm was largely spoken of in hushed tones and in French, diminishing understanding, appreciation, and transmission by younger generations who were taught to speak English exclusively.

Prior to 1993, most literature on hurricanes and their history fails to mention the Great October Storm either in general or in lists of most severe storms.18 Locals reasoned that the story was overlooked because of the relatively low economic significance of losing a remote coastal village in Louisiana relative to more developed sites along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. Locals often considered this omission part of the historical disregard of wetlands Cajun culture in the early 20th century and the poor, self-subsistent, uneducated, French-speaking Cajuns of southeastern Louisiana that comprised it. Nonetheless, the great storm forever changed family structures and settlement patterns, which led to new communities in Lafourche and Jefferson Parishes that emerged as state and national leaders in seafood, oil and gas exploration and servicing, and ship-building.

For the past 50 years, fishing camps on Chêniѐre Caminada have come and gone as milder hurricanes traversed the area and reorganized real estate, damaging construc-tions and eroding the rapidly disappearing coastline (Britsch and Dunbar 1993). For decades, there have been no permanent homes on the land. The historical Chêniѐre Cemetery has fared better than other coastal cemeteries, which are largely collapsing and disappearing as coastal marshes subside and suffer incursion of saltwater (Louisiana Cemeteries 2013). Nontheless, the Chêniѐre Cemetery becomes inundated at high tides, and its last oak trees have died salty deaths.

Folklore Processes: The Community as Classroom

Our efforts in producing a meaningful, lasting community education event regarding 19th century Chênière Caminada and the 1893 storm involved a holistic approach at creating a sense of place. In retrospect, the activities we designed parallel the Cultural Perspectives on Place and Event outlined by Howard and Sommers (2002).19 In particular, we used available resources to elucidate and re-create language and dialect, foodways, geography and ecology, landscape and land use, soundscape, religion, material culture, customs, the seasonal round, oral narrative, occupational folklife, placename origins, folk groups, and settlement history. Here, we share our major planning experiences adaptable to other community education events.

Organize Planning and Production. A diverse, active committee with specific skillsets and networks is essential. In preparation for the centennial of the Great October Storm, a committee under leadership of one of the authors (WC) convened to discuss ways to commemorate the event that had refashioned their communities. Called the Cheniere Hurricane Centennial (CHC, which became the name of the event), the committee assumed the complex mission to commemorate a natural disaster of historic proportion, mobilize multiple local communities to recognize and remember their heritage, and return the storm to its rightful place in written history. The overarching goals of the CHC were to produce a proper memorial for the hundreds of ancestors who perished as well as an educational event for the thousands of survivors’ descendants. Committee meetings and open-community discussions were held in the villages along Bayou Lafourche, particularly Golden Meadow and Côte Blanche (modern-day Cut Off), which had been established by relocated survivors. The committee decided to program a “Centennial Weekend” October 1-3, 1993. Specific days and activities included Memorial Friday, involving rededication of the Chênière Cemetery and church bell, Folklife Saturday, which manifested in a daylong folklife festival, and Reunion Sunday, including traditional church services and family gatherings.

Produce Keepsake Literature. By producing written keepsakes, current generations can document events important to a community and thereby encourage future generations to recognize their importance. The CHC determined it imperative to produce substantial, inexpensive, and widely available keepsake literature. One of the authors (JPD) co-authored The Chêniѐre Caminada Story (1993), an 80-page paperbound book that included historical photos, a brief history of the community, the story of the hurricane and its aftermath, historical newspaper articles, a list of survivors and victims, Centennial Weekend activities, and a bibliography with further reading resources. Through writing and historical photographs, the book involved many of the cultural perspectives of Howard and Sommers (2002). And, in an effort to perpetuate community learning and remembrance, the CHC published beginning in 1994 (Réfléchir 1994) and until 2022 five popular hardbound collections of historical photographs collected from Folklife Saturday and additionally contributed by the community.

Involve Press and Public Relations Efforts. It is crucial to publicize dates and activities in advance. With the advent of the Internet and social media, this is easier than ever. In 1993, two local newspapers produced tabloid supplements on the Centennial Weekend and news articles related to the hurricane’s history. Some articles found themselves in national syndication, publicizing the event to a much broader audience.

Incorporate Community Religious Activities and Other Deeply Held Cultural Practices. Addressing what a community deeply believes and practices helps ingrain community education across generations. Because the largely French-speaking population of 19th century Chêniѐre Caminada was largely Roman Catholic, the committee determined that memorial religious events were in order. A multi-denominational rededication of the Chêniѐre Caminada Cemetery was produced October 1, 1993. A large monument of engraved marble commemorating the centennial was formally aside the cemetery and facing the highway. The legendary silver bell, now in the Our Lady of the Isle belfry on Grand Isle, was rededicated. Memorial masses were followed by tours of church cemeteries in those villages formed in the storm’s aftermath. Graves of survivors were marked with commemorative foam-core markers featuring the CHC logo. Many 19th century and even more modern tombs bear epitaphs beginning Il repose ici (“Here lies”), in the first language of those represented.

Include Folklife Discovery and Interpretation Events. The objectives of such community education are to elucidate, discover anew, and interpret older aspects of folklore and folklife. Ideally, this involves interactions of professional scholars with community tradition bearers. On Folklife Saturday, the CHC produced an interpretive folklife festival at the Cut Off Youth Center. The festival included discussions by scholars on music, vernacular architecture, historical wetlands occupations, and Gulf Coast literature. Other events featured music, storytelling, Le parc aux petits (a playground featuring historical outdoor games), a Comment tu le dis? stage (capturing the novel technical jargon of traditional folk occupations in the coastal marshlands), displays and exchange of historical family photographs, a genealogy research room, and an oral history room with video capture.

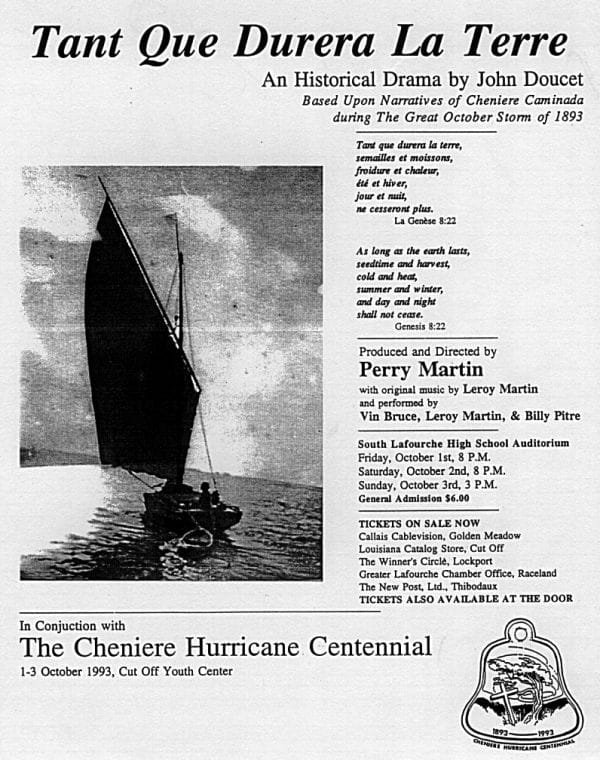

Consider Re-enactments of Historical Folklife. Perhaps the most enduring Centennial Weekend event was production of the theatrical play Tant que Durera la Terre.20 Selected by the CHC from an open competition and written by one of the authors (JPD), the play was based on narratives of life on Chêniѐre Caminada told through the imagined life of his great-great grandfather, a first-generation Chênière oysterman. The narrative weaves through the historical folkways and legends surrounding the storm. Opening precisely 100 years after landfall of the great storm, the play featured a large cast of local and semiprofessional actors onstage at South Lafourche High School in Galliano, LA.

Much of the history of Chêniѐre Caminada, as well as community culture and storm lore, was told through Tant que Durera la Terre. Such re-enactments are challenging to effectively produce: In our case, we had not only a century-old story to convey but also one that involved emulating the sensorial experience of a hurricane. Here are some considerations that made our production successful and memorable.

- Include well-known parts of history and folklife in the narrative and thereby reinforce the sense of place. Such inclusion effectively connects prior audience knowledge with the theatrical experience.

- Avoid lecturing. “Show. Don’t tell.” With lots of history to convey, it is too easy to render information and notes as dialogue. Your writer(s) should carefully and cleverly develop ways to integrate educational information into character action and dialogue without those ways “seeming” to lecture to the audience.

- Establish sense of place and sense of time. Accurate geography and landscape are essential. Use of the vernacular is extremely effective.

- Invoke both Melpomene and Thalia. The mission of the stage is to entertain, no matter how tragic the story may be. Include carefully interspersed light-hearted and even comedic scenes.

Original playbill for premiere of Tant que Durera la Terre, showing dates, location, and sponsorships.

Legacy

Over the next 20 years, Tant que Durera la Terre has been produced multiple times21 and has renewed interest in the theatrical arts in communities along Bayou Lafourche, with creation of local troupes and new community, school, and restaurant venues. A number of grassroots organizations and individuals began to take serious stock in collecting private, historical, and cultural artefacts held by communities, particularly in light of northward population shifts due to coastal land loss and subsequent loss of economic opportunities. Gathering physical donations and loans from fellow townsfolk, historical centers arose in Golden Meadow and Galliano, featuring displays and artefacts of local history and culture, with notable emphases on historical hurricanes.22 The South Lafourche Public Library in Galliano archived photos and genealogy records captured by Folklife Saturday events.

The authors remain active in keeping commemoration of the Great October Storm and its impact alive. We regularly host public lectures, deliver classroom talks on rural history, deliver readings of works by period authors, and write news articles. Our university students are regularly engaged in forensic research regarding historical Chêniѐre Caminada for archiving at Nicholls State University (Thibodaux, LA). Multiple modern novelists have published fictional accounts of life on Chêniѐre Caminada relating to the great storm.23

Any study of fin-de-siecle Chêniѐre Caminada is limited by lack of documentary resources. The early Cajun community transmitted knowledge and history by oral tradition, and much of the local 19th-century population was not formally educated and not able to write.24 Geographical remoteness contributed to its relative isolation from scholarly attention. It was important for the CHC to inaugurate a collection of major and minor resources to develop a comprehensive account and archive of historical Chêniѐre Caminada. The authors in conjunction with other scholars and writers have contributed to a growing collection and database of written and recorded resources housed in the Archives and Special Collections at Nicholls State University.

Perhaps the most profound aspect of the legacy of the CHC was producing a large, complex event of community engagement, cultural relevance, and historical significance that had resulted in widespread popularity. The event reached far beyond modern, post-Chêniѐre communities and the boundaries of Louisiana. Including locals, an estimated 15,000 visitors and scholars from around the U.S. and overseas, particularly Canada and France, attended Centennial Weekend. Since then, journalists and writers of nonfiction books on hurricanes and natural disasters have taken note of the Great October Storm of 1893, a phenomenon that was not frequent prior to CHC events in October 1993.25

Natural disasters, like hurricanes, are great forces that enter and alter people’s lives as well as their perceptions of reality. In coastal Louisiana, hurricanes are a basis of our lifeways and settlements. They create history and lore and are a basis of our folklife. After forcing people to seek shelter in advance of landfall, they have an ironic way in their aftermaths of bringing communities together for the common good and for common grieving and rebuilding. It was thus after the Great October Storm of 1893, and it was thus after Hurricane Ida—a severe Category 4 hurricane that struck the post-Chêniѐre communities in late August 2021. As we have learned over the past 30 years, even 100-year-old hurricanes can mobilize a community.

Additional Resources for Educators

The success and impact of the events of Centennial Weekend suggest a model for other community education events based on history, culture, and lore. We recognize the potential value of our experiences to educators and community event planners as well as to creating new opportunities to study folklore. We hope that our story will be useful in envisioning, planning, and producing community education events. In addition to the practical recommendations included in our article, we also recommend the following teaching resources.

Written in Stone, by History Detectives https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/educators/technique-guide/written-in-stone

Cemeteries often provide useful historical information and insight into folkways. Epitaphs themselves are intrinsically informative as documents of surnames, dates, and sometimes geographical nativity and family structure, and they are also occasionally accompanied by engravings and images that reveal occupations and other community traditions.

Documenting Maritime Folklife: An Introductory Guide, by the American Folklife Center https://www.loc.gov/folklife/maritime

An excellent resource particularly useful to riparian and coastal community schools, this website provides advice and methods for planning and documenting artefacts, including note taking, interviewing, photography, and archiving.

Hurricane Resources and Opportunities for K-12 Educators, by Louisiana Division of the Arts https://www.louisianavoices.org/hurricanes_k12.html

Using Hurricanes Katrina and Rita of 2005 as primary examples, these units, which include ideas employing creative artwork, explore the classroom’s ability to manage student stress and trauma following destructive and tragic events.

Oral Traditions: Swapping Stories, by Louisiana Division of the Arts https://www.louisianavoices.org/Unit5/edu_unit5.html

This site provides a wealth of reading and viewing resources, including links to the storytelling collection Swapping Stories: Folktales from Louisiana (Lindahl et al. 1997) and an extensive bibliography. Lesson 7: Personal Experience Narratives may be particularly useful.26

Sense of Place, by the Walden Woods Project

https://www.walden.org/education/curriculum-collection/sense-of-place

This website offers curricula that help students establish sense of place through fieldwork and writing—and the lessons are written by students!

Material Culture: The Stuff of Life, by Louisiana Division of the Arts https://www.louisianavoices.org/Unit7/edu_unit7.html

Additional sites from Louisiana Voices: An Educator’s Guide to Exploring Our Communities and Traditions can be adapted to communities and folklife investigations beyond Louisiana.

The authors are each descended from families who survived the Great October Storm of 1893. They are available as advisors for planning community events involving historical and cultural education.

John P. Doucet, PhD, is Professor and Dean of the College of Sciences and Technology and Director of Coastal Initiatives at Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, LA. He is author of Tant que Durera la Terre, the official theatrical play of the Cheniere Hurricane Centennial, and co-author of The Cheniere Caminada Commemorative.

Annie Doucet, PhD, is Assistant Professor of French at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. She has conducted field studies on colloquial French across southern and coastal Louisiana.

Windell Curole, DSci, is Director of the South Lafourche Levee District, headquartered in Galliano, LA. He served as Chair of the Chêniѐre Hurricane Centennial. For his efforts in producing the Centennial event, he was awarded Citizen of the Year by the Lafourche Gazette.

Works Cited

Bastian, David F. and Nicholas J. Meis. 2014. New Orleans Hurricanes from the Start. Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Company.

Britsch, L.D. and J.B. Dunbar. 1993. Land-Loss Rates—Louisiana Coastal Plain. Journal of Coastal Research. 9:324–38.

Craft, Lucy. 2021. Japan Rebuilt an Entire Tsunami-Flattened City on a Man-made Hill but Many Still Can’t Face Life There. CBS Saturday Morning, 4:30, March 11. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/japan-tsunami-2011-fukushima-rebuilt-city-rikuzen-takata-residents-still-scared/?intcid=CNM-00-10abd1h

Dunn, Gordon E. and Banner J. Miller. 1964. Atlantic Hurricanes. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Falgoux, Woody. 2017. Rise of the Cajun Mariners: The Race for Big Oil. New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

Falls, Rose C. 1893. Chêniѐre Caminada, or The Wind of Death: The Story of the Storm in Louisiana. New Orleans.: Hopkins’ Printing Office.

Field, Martha R. 2006. Louisiana Voyages: The Travel Writings of Catharine Cole. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Forrest, Mark. 1894. Wasted by Wind and Water: A Photo and Pictorial Sketch of the Gulf Disaster. Milwaukee, Wis.: The Art Gravure and Etching Company.

Gorley, Linda G. 2010. Chêniѐre Caminada and the Tidal Wave of 1893: The Incredible Survival of Claydomere Paul Lafont. Bloomington: AuthorHouse.

Grimeau, Rev. F.J. 1996. The Mission of Chêniѐre Caminada. In Lafourche Country II: The Heritage and Its Keepers, eds. Stephen S. Michot and John P. Doucet. Thibodaux, La.: Lafourche Heritage Society.

History [History of Hurricane Occurrences Along Coastal Louisiana}. 1972. U.S. Army Engineer District, Corps of Engineers, New Orleans.

Howard, Diane W and Laurie Kay Sommers, eds. 2002. Folkwriting: Lessons on Place, Heritage, and Tradition in the Georgia Classroom. Accessed July10, 2022, https://archives.valdosta.edu/folklife/docs/folkwriting-book.pdf.

Leonard, Craig, Sr. 2016. Unto the Last Seed. Sedona, Ariz.: Sojourn Publishing.

King, Grace. 1894. At Cheniere Caminada. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 88.528, May.

Landry, Marjorie. 1993. Stories My Grandparents Told Me: Student Essays on Lafourche Heritage. Thibodaux, La.: Lafourche Heritage Society.

Lindahl, C., Maida Owens, and C. Renée Harrison. 1997. Swapping Stories: Folktales from Louisiana. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Looper, Robert B., John Doucet, and Colley Charpentier. 1993. The Chêniѐre Caminada Story. Thibodaux, La.: Blue Heron Press.

Louisiana Cemeteries [Louisiana cemeteries shrinking, washing away after years of erosion, powerful storms like Katrina]. 2013. Accessed June 21, 2022, https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/louisiana-cemeteries-washing-article-1.1232039.

Louisiana Voices [Louisiana Voices Folklife in Education Project]. Accessed July 14, 2022, https://www.louisianavoices.org/edu_home.html.

Norcross, B. 2006. Hurricane Almanac 2006. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Page, Jennifer and John P. Doucet. 2010. Literati on the Isle: Nineteenth Century Authors on the Louisiana Gulf Coast. In Lafourche Country III: Annals and Onwardness, eds. John P. Doucet and Stephen S. Michot. Thibodaux, La.: Lafourche Heritage Society.

Perrin, Patricia E. 1977. Storm Lore About the Hurricanes of 1893 and 1915 in the Coastal Areas of Lafourche and Terrebonne Parishes. MA Thesis. University of Southwestern Louisiana, Lafayette.

Pitre, Glen. 2020. Advice from the Wicked. New Orleans: Cote Blanche Productions.

Pitre, Loulan J., Jr. 1996. Chêniѐre Caminada, A Late Nineteenth Century Coastal Cajun Community. In Lafourche Country II: The Heritage and Its Keepers, eds. Stephen S. Michot and John P. Doucet. Thibodaux, La.: Lafourche Heritage Society.

Plater, Ormonde. 1971. The Hurricane of Chêniѐre Caminada: A Narrative Poem in French. Louisiana Folklore Miscellany. 3.2:1-11.

Reeves, W. D and D. Alario, Jr. 1996. Westwego from Chêniѐre to Canal. Jefferson Parish Historical Series Monograph XIV. Westwego, La.: Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Alario.

Réfléchir [Réfléchir: Les Images des Prairies Tremblantes, 1840-1940]. 1994. Cut Off, La.: Chêniѐre Hurricane Centennial.

Rouse, Norris H. 1979. From Pirate Booty to Parish Belfry: The Bell of Chêniѐre Caminada. Acadiana Profile, Sept./Oct.

Rogers, Dale. 1985. Retreat from the Gulf: Reminiscences of Early Settlers of Lower Lafourche. In Lafourche Country: The People and the Land, ed. Phillip D. Uzee. Thibodaux, La.: Lafourche Heritage Society.

Russel R. J. and H.V. Howe. Cheniers of Southwestern Louisiana. Geographical Review, 25.3:449-61

Smith, Debra. 1999. Hattie Marshall and Hurricane. Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Company.

Terrebonne Life Lines, 6.1:50-65

1893 Chêniѐre [1893 Chêniѐre Caminada Hurricane] 2021. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1893_Cheniere_Caminada_hurricane.

Endnotes

1 The poem “L’ouragan de la Chênière Caminada” was first published in Plater (1971), who transcribed it from written French and translated it into English. The representation here is a new literal translation by one of the authors (AD).

2 The number of causalities differs in various resources. As declared by the Times-Democrat, 2,000 is generally considered the gross estimate of total mortality across the path of the storm from the Gulf to the Atlantic Coast during the week of October 1-6, 1893, with vastly more deaths occurring along the Gulf Coast in Louisiana where the storm was most intense. The mortality at Chêniѐre Caminada is variously estimated between 800 and 1,200. Precision is a challenge for multiple reasons: paucity of record keeping in the remote village, the temporary residence of boarders who owned no property but worked seasonally in the fishing industry, and the number of undocumented bodies buried in the aftermath. At mortality of 2,000, it remains the second largest disaster in U.S. history, following the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900.

3 This beach image and other photographs originally appeared in the contemporary account by Forrest (1894).

4 See Note 3.

5 Jefferson Parish tax rolls for 1894 show that many Chêniѐre Caminada landowners had abandoned and forfeited their land and water property by failure to pay annual property taxes, which ranged from $1 to $12. See Terrebonne Life Lines (1987). Similar property abandonment occurs following other major storms, as seen in the New Orleans region following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and as is emerging in Lafourche and Terrebonne Parishes after Hurricane Ida in 2021.

6 For the story of families relocating to Westwego, see Reeves and Alario (1996).

7 The term chêniѐre is French for “oak grove,” and it was from this Louisiana colloquial usage that geologists first described the distinctive geological structures deriving from prehistoric beachheads. See Russel and Howe (1935).

8 See Note 3. An additional substantiating account is provided by the painting Surf Bathing, Grand Isle (c. 1850-1890), by American artist John Genin, curated at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Genin illustrates the common topology of the barrier island and nearby Chêniѐre Caminada. To the fore of the painting is a barren beach (and here Genin includes surf, bathers, and beach houses), to the rear is a lush oak grove, and in the center the artist strikingly depicts hundreds of downed trees. This downing, either for landscaping or for market lumbering, was likely a common enterprise in the mid-to-late 19th century along the Louisiana coast.

9 An alternative explanation for clearing the land is capitalizing on the lucrative value of oak as lumber for construction of fishing vessels and larger ships.

10 It is difficult to imagine characterization of these villagers as lazy. This opinion may derive from a contemporary view of their beach residence, seasonal fishing lifestyle, and relative personal income. Many of the native Louisianans residents on Chêniѐre—Acadians and others—were drawn there, leaving behind property to the north where farming as petits habitants and the 19th-century struggles with that farming economy required group labor and relatively harder work, as well as producing lower income.

11 Some of his French-language narratives have been translated. See Grimeau (1996). In different sources, his surname is variously spelled Grimaud and Grimeaux.

12 Nearby Grand Terre island, just southeast of Grand Isle, was a documented haunt of the legendary Jean Lafitte and his privateers.

13 See Falls (1893).

14 For multiple examples, see Falls (1893), King (1894), and Field (2006). Field collects the works of travel writer Catherine Cole, who penned an account of Chêniѐre Caminada around the time of the great storm. For a general accounting of authors writing about this coastal region during the period of the great storm, see Page and Doucet (2010).

15 A strikingly similar situation occurs today among survivors of the earthquake-tsunami-nuclear disaster that left 22,000 dead or missing along the northeast coast of Japan. At the 10th anniversary of the disaster in 2021, one informant told CBS News, “We lost everything. You don’t count what you lost—you lost everything. It’s kind of a defensive mechanism in psychology. You try not to think about what you have lost… From what I can see in my neighbors and people, they are still quiet. We prefer not to go back to the recent memories. It’s difficult to quantify, but it will be very long lasting.” (Craft 2021)

16 Today, this highway is known as Louisiana Highway One (LA 1). LA 1 connects all modern post-Chêniѐre communities along Bayou Lafourche and crosses the entire state diagonally, from Shreveport to Grand Isle. Before concrete paving in the 1930s, the roadbed consisted of marsh clam shells (Rangia cuneata), which grow to enormous populations along the Louisiana Gulf Coast. Due to extreme land loss consequent to subsidence and saltwater incursion from the Gulf, the stretch of LA 1 south of Golden Meadow to the terminus of Bayou Lafourche at the coastline is currently being transformed to an elevated causeway to serve the coastal fishing and recreational economy as well as the major oil field service corridor at Port Fourchon.

17 Sometimes referred to as “fire spirits,” le feu follet is the subject of a common wetlands Cajun folktale involving the sometimes spherical, sometimes planar glow that can be observed floating over coastal marshes. In the colloquial variant, spherical feux follets rise above marshland cemeteries and represent the ghostly heads of unbaptized children rising to escape their earthen purgatory. For another variant, see Lindahl et al. (1997). One natural explanation for the phenomenon is energy released in the form of heat and light from the biological decay of subsurface detritus common in wetland environments.

18 Case in point: Atlantic Hurricanes by Dunn and Miller (1964) is a Louisiana-based publication by meteorologists from the National Hurricane Center. The 1893 Chêniѐre hurricane is listed in two tables but not rendered into narrative like storms of lesser severity and mortality.

19 For a concise outline adaptation, see Louisiana Voices https://www.louisianavoices.org/Unit4/edu_unit4.html.

20 “As Long as the Earth Lasts,” from the first line of the Covenant that God spoke to Noah after the Great Flood. Though titled in French, the play is written in English, and performances typically include unscripted insertions of recognizable, colloquial French phrases according to the actors’ natural capabilities. The title thus represents multiple aspects of Chêniѐre history and culture: language, religion, and natural disaster. An excerpt of the play appears in Looper et al. (1993).

21 In 1996, Tant que Durera la Terre was awarded the Louisiana Native Voices and Visions Award and led to an extended avocation for the first-time playwriter, who in the ensuing years would compose an additional 12 plays all based on the history and culture of the Bayou Lafourche region and all produced at Louisiana theaters.

22 Ironically, though sadly, both centers were destroyed by Hurricane Ida, which made landfall on August 29, 2021.

23 For multiple examples, see Smith (1999), Gorley (2010), Leonard (2016), and Pitre (2020). Pitre was a member of the CHC Committee. Readers may recognize the name of his production company from the Works Cited entry.

24 See Pitre (1996). In 1880 Chênière Caminada, less than 24% of males over age five and less than 8% of females over age five were literate.

25 For two examples, see Norcross (2006) and Bastian and Meis (2014).

26 This strategy was used to public acclaim among schools in Lafourche Parish, La., in 1993. In that year, the Lafourche Heritage Society published Stories My Grandparents Told Me (Landry, 1993), a 187-page paperbound collection of personal experiences collected by students from their grandparents. In the process, a contest was established for the best stories from each level of school. Several reminiscences of the 1893 storm appeared in the collection.