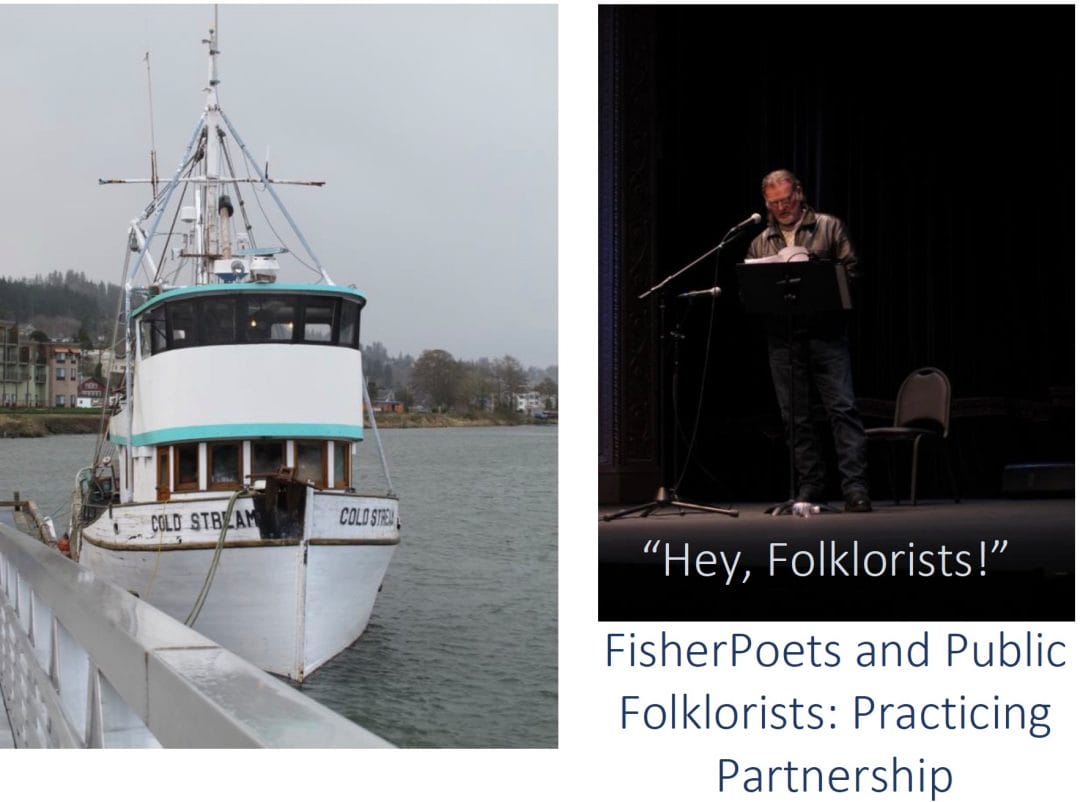

Dave Densmore’s boat, the Cold Stream, anchored at Pier 39, Astoria, Oregon (L), and Dave Densmore at the Liberty Theater, Astoria, Oregon (R). Photos by Riki Saltzman, courtesy of the Oregon Folklife Network.

The FisherPoets Gathering (FPG) seduces audiences with poems, songs, and stories in celebration of Northwestern commercial fishing heritage. Men and women who earn their livelihood fishing assemble to catch up on news, renew old ties, and make new ones. This annual event takes place in scenic Astoria, Oregon, at the mouth of the Columbia River, and brings together local commercial interests, heritage, and traditional expressive culture for three nonstop days of performance. The Gathering happens in the dead of winter—the last weekend in February. While this may seem an odd time for most of us to go traipsing off to the wet and windy northwest coast, it’s downtime for most Pacific Northwest fishermen. As poet, fisherman, teacher, and FPG founder Jon Broderick has noted, however, crabbers and long-liners are still hard at it. Regardless, this event warms and renews all who take part.

The FisherPoets Gathering started in 1998, when a few commercial fishermen—the term that both men and women prefer—decided to create a get-together to share their songs, stories, and poetry. Fishing has long inspired a variety of expressive culture centered around work; witness the long history of sea shanties and work songs from those who make their living on water. In the 20th century, commercial fishermen began to communicate over radio during long hours at sea. Some of this was just chatter, and some was more creative storytelling and versifying. With a focus on the latter, the FPG welcomes commercial fishermen to come together to celebrate who they are; mourn their losses; laugh at their mistakes; tease each other; talk about politics, regulations, and the economy; and then write movingly in poetry and prose about who they are, what they do, and even the fish they catch. The Gathering speaks to the significance of the Pacific Northwest’s historic fisheries and fishing communities and their relationship to the environment, local economies, and local cultures.

Of course, the event was not originally intended to be public entertainment. As Hobe Kytr firmly told me in our first email exchange, “This is a celebration of commercial fisheries by and for commercial fishers.” Jon Broderick responded to my long-winded offer to volunteer at FPG in his usual laconic way: “I’ll say we need help. See [the volunteer schedule]. Want to take a shift?” I did, and I thoroughly enjoyed myself. For me, this was a folklorist’s dream—hearing working men and women recite poetry and prose and sing songs about their occupational trials and triumphs. What a kick!

Relationships Matter in Folklore and Education

One of the main reasons I was drawn to folklore, as an undergraduate and then as a career choice, had to do with my love for hearing stories, whether they are folk tales, oral histories, or personal experience narratives. My first folklore fieldwork was with watermen on the Chesapeake Bay in 1975. I was an undergraduate in a folklore and fieldwork class that folklorist Bob Bethke and historian Jim Curtis, University of Delaware faculty, were team teaching. I marvel now at their courage in first mentoring then setting loose a group of college students to document the stories of working watermen. In 2012, after over three and a half decades of folklore practice across the U.S. and the U.K., I started a new job at the Oregon Folklife Network (OFN), the state’s designated folk and traditional arts program. I was looking forward to hearing new stories in new places. Jens Lund, then the folklorist for Washington State Parks, had told me about the FisherPoets Gathering some years before; once he knew I’d be taking the OFN position, he urged me to attend the 2013 Gathering. He introduced me to FPG organizers Jon Broderick (commercial fisherman, retired high school English teacher, fisherpoet and singer/songwriter) and Hobe Kytr (marine historian and singer/songwriter).

Since 2013, the OFN has partnered with the FisherPoets Gathering to document fisherpoets, their work, and their occupational poetry and prose. As folklorists who have the privilege to interview fisherpoets, our appreciation for the artistry required to make hard physical labor into verbal art that invokes community has led to an ongoing relationship as well as friendships and fish. OFN’s incorporation of the annual FPG into our mission to mentor the next generation of public folklorists has been a further consequence. It’s become one of my greatest pleasures to introduce University of Oregon Folklore and Public Culture Program students to the annual Gathering and to folklore fieldwork—a bit of paying forward of my own first foray into folklore as a student. The FPG provides a perfect first fieldwork experience—a physically and temporally bounded event that immerses all who attend in the traditional expressive culture of commercial fishermen. While most UO Folklore graduate students attend FPG only once, a few attend multiple years because they’ve decided to focus their MA theses on some aspect of the event; both Brad McMullen and Julie Meyer, noted below, researched and wrote about how gender affects the form, content, and performance of fisherpoetry.

Fieldwork Ethics and Community Relationships

Before traveling to FPG, students must learn about the ongoing relationship we have with the Gathering and our responsibility to document the poets respectfully. OFN has been doing this since 2013, so we have archived over 40 interviews. I have students read a paper that I wrote describing the event and OFN’s previous collaborations with FPG and individual poets. We talk about what commercial fishermen do, the dangers they face, how at least one boat goes down each year, and how this event is THEIR reunion; we are privileged to have an insider track. That privilege and trust come from being open and collaborative, inviting and paying fisherpoets for performances and workshops outside FPG, and helping periodically to write grants to fund poets’ travel to FPG. Letting students know that they are part of a long tradition of folklorists’ documentation is really important, as is emphasizing that their behavior reflects on OFN and UO’s Folklore Program.

Fieldwork Rules—Do No Harm!

Each year, OFN offers UO Folklore students the opportunity to travel to Astoria for the FisherPoets Gathering. Part of the experience is getting there, which includes a four-hour drive to Astoria from Eugene, and the transition into this once-a-year world; usually it’s pleasant, but some years we’ve driven through mountain snow as we cross from the Willamette Valley over the Coastal Range. We check into the same hotel as the poets and enjoy our first reunions with old friends. We tear ourselves away and head over to the Gear Shack. This temporary gift shop is where everyone registers and receives that all-important button that allows access to the event—volunteering for a three-hour stint at a performance venue gets us our admittance buttons. The Gear Shack sells fisherpoets’ chapbooks, books, CDs, DVDs, and art; it’s also the site of a silent auction.

Students attend at least one performance of a fisherpoet whom the student will interview as well as many other performances, film showings, and workshops as they can fit in. Besides the official program, it’s important to pay attention to opportunities to talk informally with the fisherpoets. The deep conversations occur back at the hotel, after performances are done for the evening, and I encourage students to join in and get to know the fishermen. They all bring food and beverages to share, and it’s polite for us to do so, too. Zoe Steeler (BA, UO Folklore, 2016), then an undergraduate Folklore major, observed:

During the Gathering there was a sort of energy; the town came alive during the event. So many businesses had “Welcome FisherPoets” signs hanging in their front windows. Everywhere I went, I saw someone else that was involved in the Gathering. The whole town was a part of it. The lobby of the hotel we stayed at was the site of casual after-hours groupings; every restaurant I passed was filled with people sporting fisherpoet buttons [the entry “ticket” to admit everyone to performance venues], and the maritime museum opened their doors to the Gathering as a place for talks. The buttons were like a badge of community, a sign of camaraderie. The program for the event was a local newspaper. It felt like everyone in this town was involved and connected with the event.

Some weeks before we leave for Astoria, I meet with all the students (usually those who are part of my Public Folklore or Folklore and Foodways class, so they’ve already gotten an introduction to fieldwork) and go over what to expect from the weekend. We discuss the event in general, logistics like making sure to bring food and drink to share for evening after-hours get-togethers, and how to do the actual interview.

There are usually several opportunities to share experiences during meals at FPG, and we debrief during the car ride back to campus. We also talk about the experience during class or another gathering back in Eugene. And we make sure to send those digital interviews along with a thank-you email to those we’ve interviewed. Manners count!

Folklore student Kayleigh Graham interviewing Rob Seitz at the Columbia River Maritime Museum. Photo by B McMullen, courtesy of the Oregon Folklife Network.

UO’s Folklore students have eagerly taken up OFN’s offer to journey to document fisherpoets at the annual Gathering. Steeler reflected on the event’s transformational impact:

The FisherPoets Gathering was an incredibly special event. It was my first time participating in any sort of folkloric fieldwork, and I found it to be something I definitely want to do again. I learned how to do interviews in a real-world setting, and I got to witness the finer aspects of fieldwork from people I like and respect. . . . I got to be a part of something that I will never forget. On this trip I was able to finally find the work that I want to be a part of in a long-term manner.

The Fieldwork Interview

The fieldwork interview is an important part of the learning experience, which includes scheduling the interview, conducting it, creating the metadata (audio log, datasheet, fieldnotes, reflection), and collaborating on an OFN newsletter feature. We start with looking over the FPG website, In the Tote recordings and bios, and performance schedules, I go over fieldwork etiquette and potential issues in general:

- Make sure to read any posted bios and writings of the poet you’ll be interviewing.

- Be respectful of people’s time.

- Introduce yourself.

- Listen and try to nod instead of responding verbally.

- Try not to interrupt your interviewee.

- Use the recommended questions as a guide.

- Listen actively and ask follow-up questions.

- Thank your interviewee and offer to send him/her the digital recording and any photos you have taken of him/her.

In our discussions, we also cover the logistics as well as the ethics involved through a series of topics—cultural context, how to ask questions, and how to listen. I provide examples of when things have gone wrong in fieldwork situations (not just at FPG) and how to turn what sounds like a dumb question into a way to gather more information; if you act as if you know the answers, why should our interviewees provide their own? Because this class session is about fieldwork in general, we do cover issues that students might realistically confront in a variety of fieldwork situations, from general surveys to contract work for a particular employer. We discuss how folklorists might respond to a fieldwork scenario when they don’t agree with the person they are interviewing. We also spend time having students reflect upon who they are and who they may represent when doing fieldwork.

To give everyone experience in how to ask and how to listen, we do practice interviews with each other. We start with reading “Writing as Alchemy: Turning Objects into Stories, Stories into Objects” (Liu and Sunstein 2016). Then we talk about the specifics of the annual Gathering. Students look over the FPG website and a particular year’s list of participants, listen to some In the Tote recordings, and check out available biographies and writings for those they will be interviewing. Jon Broderick usually provides a suggested list of fishermen to interview along with their contact information. After an initial explanatory email to all from me, students take the lead and schedule their interviews. First, they look over the schedule to learn when their poet will be performing; the interviews take place the next day at the Columbia River Maritime Museum (thanks to the very gracious director and staff). The side bar lists suggested questions and topics, but interviewing is much more an art than a science; listening to responses and asking follow-up questions is more important than following a script.

Interview Notes

General topics

- How a particular fisherman got into commercial fishing

- How the fisherman became a fisherpoet

- How the FPG is meaningful to the fisherman

Potential interview questions

- How did you get into fishing?

- What is your first memory of fishing?

- From whom did you learn?

- Why do you continue to do it?

- What kind of dangers have you faced? Funny moments?

- What makes a good fisherman? A good deckhand? A good captain?

- Do you work outside of fishing?

The writing experience

- How and why did you start writing poetry and/or prose?

- Did you write poetry before you fished?

- When did you write your first poem? About fishing?

- What makes a good poem/prose piece?

- What’s your way of starting, writing, and revising a poem?

The Gathering experience

- Why did you start coming to FPG?

- How long have you been coming and do you come every year?

- What’s meaningful to you about FPG?

- Who are your favorite fisherpoets and why?

- What makes a good fisherpoet?

Commercial fisherman, fisherpoet, and former social worker Tele Aadsen, whom folklorist Brad McMullen interviewed a few years ago, described the interview experience as a “guided meditation.” I love this phrase because it gets at the heart of what a good interview can do and how to give back to the interviewee. The process of ethnographic interviewing starts with pre-formulated questions, usually based on previous work—research or fieldwork—with a particular person in a particular field. A good interview uses those questions as a guide but also, crucially, involves active listening, commenting when appropriate, and asking follow-up questions. In our interviews with fisherpoets, we ask both about the work and the creative writing process. Most people, even these creative folks, don’t really think explicitly about their process. When we as folklorists ask them how they do what they do, how they process their fishing experiences into poetry and prose, we are trying to elicit those implicit processes—and that’s not always easy to articulate. The interview process is itself a creative collaboration that builds from basic and general questions to more intimate ones. I almost always end an interview with the question, “Why do you do it [whatever the traditional art is]?” Engaging deeply with those we interview about their work and the resultant traditional art invites interviewees to think and talk about how they process experiences into expressive forms.

Moe Bowstern at the Liberty Theater, Astoria, Oregon. Photo by Riki Saltzman, courtesy of the Oregon Folklife Network.

The creative products of folklorists—including this article—may also include blogs and newspaper articles. Read some student examples at these links: https://blogs.uoregon.edu/ofnblog/2020/07/16/fisher-poets-gathering-2020, https://blogs.uoregon.edu/ofnblog/2018/04

Folklife, Fieldwork, and Paying It Forward

The FPG gang seems happy to have us around, and the graduate students reported back to me after the 2014 Gathering, which I couldn’t attend, that the fisherpoets had taken to greeting them around town with a “Hey, Folklorists!” Now emcees thank us from stages and the FPG acknowledges us as partners on their website. We appreciate that we’ve earned their trust, and we remain sensitive with the relationships; giving back to those communities we document is critically important. Julie Meyer’s exhibit Shifting Tides: Women of the FisherPoets Gathering and her MA thesis on the same topics are great examples of just that. Meyer listened well to her interviewees as they shared their processes as fishermen, writers, and performers. She also proved her mettle by going to Bristol Bay for a few weeks over two summers to learn and do the work of a set-netting crew. Both her exhibit and her thesis exemplify the results of her collaboration with fisherpoets and with OFN’s exhibit curator and staff. Likewise, the articles that students produce for OFN’s newsletter include student reflections on their experiences as folklorists as well as their fisherpoet documentation. My role as instructor and folklorist includes documenting students’ ethnography and sharing those images and reflections with both them and the public. Becoming a folklorist, like becoming a fisherman, is a process; it happens gradually—and by doing the work. Reflecting on her experiences, Meyer wrote:

Overall, I went into the FisherPoets Gathering with a lot of background knowledge about the fisherpoets and about the environments where they were coming from. It is my belief that a fieldworker should have as much background information as possible when going into important interviews, because without this background information individuals cannot truly reach the complex issues buried in the interviews. If we spend most of our time contextualizing and asking for basic information about terminology, I think we are missing out on the more complex issues about community and folklore. My experience at the FisherPoets Gathering vastly transformed over the year, from my first trip to the event, to my work in the fisheries, and finally my return to the Gathering. Upon my return to the 2015 FisherPoets Gathering, I feel as if I’ve finally gotten a true taste of the magic of the FisherPoets Gathering to which the community members constantly refer.

As part of the OFN, I’ve been empowered to reach out to local groups—to meet, document their traditions, and offer assistance as needed. This is an enterprise that many of us are privileged to share and indulge our curiosity about cultural traditions. We get to document the traditions, meet and sometimes become friends and colleagues with those who keep and pass them on, and, we hope, make a difference by calling attention to, celebrating, preserving, and promoting folklife—and the individuals who make it possible.

I don’t think you can be a folklorist without a passion for the lore as well as those who create it. For many folklorists, particularly those of us who work in the public sector, that admittedly selfish attraction to the artistic products, to the performances, leads us to work with individuals and then the communities to which they are attached. Their concerns and issues become ours, and sometimes it’s hard, if not impossible, to separate personal from professional life. We are not folklorists by accident, although it can sometimes seem that way.

My own theoretical interests in performance and occupational lore have helped me to understand how working men and women repurpose traditional expressive structures and forms to create and sustain community. But my involvement with the FPG and the men and women who create it and participate in it is not just about the theory; it’s about the praxis, and deeply so. And, of course, it’s about the poetry, which speaks to the traditions of an age-old occupation—and the occupational tradition of lightening the load by making art.

Conveying my love of my field and the joy I take in working with the fisherpoets has been an unexpected pleasure. Introducing students to the field of folklore and to the traditions and expressive culture of commercial fishermen is fun. I enjoy in-person reunions with the poets, many of whom I’ve become friends with outside FPG. Entering the liminal space of this reunion of hardworking, generous workers is invigorating, exhausting, and always inspiring. Former graduate student Makaela Kroin (MA, UO Folklore, 2016) put it succinctly, “My first in-depth experience with fieldwork was exciting, overwhelming, and physically and mentally draining.” She continued, “The sense of community was intense throughout the event, making it an incredibly interesting event for folklorists to document.” As Tele Aadsen wrote at the end of the 2019 FisherPoets Gathering, “Gratitude to [coast community radio, KMUN, which broadcasts the FisherPoets Gathering each year], the venues, the FisherPoets organizing committee, the performers, and the oodles of volunteers who’ve made this life-giving magic happen for 22 years now.” As it is for the commercial fishermen, so it is for us. The collective experience of the work is at the center—for the FPG has the generative power to recreate community and imbue performers, audiences, and folklorists with communitas, that feeling of oneness and flow that all good festive celebrations share. In a 2017 interview, fisherman Pat McGuire shared her thoughts about FPG with former graduate student Hillary Tully (MA, UO Folklore, 2018):

Well I think first of all it’s wonderful to be able to share what you do with like-minded people, it’s just, if you’re a fisherman in the everyday land world, you’re kind of an oddity. So it’s really nice to be around people that know what you’re talking about. But I think too because we bring out the best in each other, we share experiences, and we grow from it. And it makes me want to do better as a poet and try to communicate some of the shared experiences with other fishermen.

Lack of sleep, camaraderie with each other and the poets, and the seductive power of all good performances to take us away from ourselves make for an addictive feeling. We keep coming back for more. Finally, there is the payback, the special gift that teachers sometimes receive—to watch students learn, to see them have their own ah-ha moment as they transform into folklorists, in the process of their own performance of the work that we do.

FisherPoets 2018, Pier 39, Astoria, Oregon. Photo by Riki Saltzman, courtesy of the Oregon Folklife Network.

Rachelle H. (Riki) Saltzman is the staff folklorist for the High Desert Museum in Bend and folklore specialist for the Oregon Folklife Network, for which she served as Executive Director 2012-20. She teaches Folklore and Foodways, Public Folklore, and other courses for the University of Oregon’s Folklore and Public Culture Program. She obtained her PhD in Anthropology (Folklore) from the University of Texas at Austin and has served on the Executive Boards of the American Folklore Society and the Association for the Study of Food and Society. Her books include A Lark for the Sake of Their Country: The 1926 General Strike Volunteers in Folklore and Memory (Manchester University Press, 2012) and Pussy Hats, Politics, and Public Protest (University Press of Mississippi, 2020). ORCID 0000-0001-6648-9273

Works Cited

Liu, Rossina Zamora and Bonnie Stone Sunstein. 2016. Writing as Alchemy: Turning Objects into Stories, Stories into Objects. Journal of Folklore and Education. 3:60-76, https://www.locallearningnetwork.org/journal-of-folklore-and-education/current-and-past-issues/journal-of-folklore-and-education-volume-3-2016/writing-as-alchemy-turning-objects-into-stories-stories-into-objects.