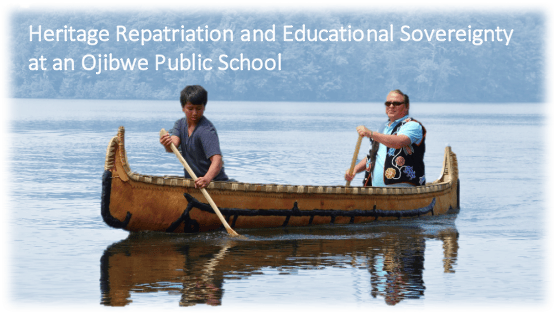

Wayne Valliere and a student from Lac du Flambeau Public School paddle the birchbark canoe during the ceremonial launch in Lac du Flambeau, June 2014. Photo by T. DuBois.

by B. Marcus Cederström, Thomas A. DuBois, Tim Frandy, and Colin Gioia Connors

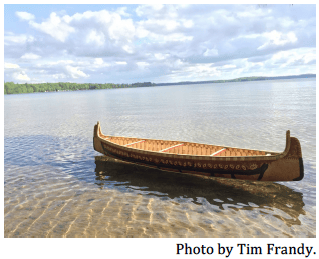

In the Western Great Lakes region, late summer is the time to harvest manoomin, wild rice, a sacred food central to the prophecy that led Ojibwe to make their home in the place where “food grows on water” (Loew 2013, 60). Growing in the shallows of lakes and rivers, manoomin (“the good seed”) is harvested in canoes poled or paddled through a thicket of tall grass-like rice stalks that emerge above the surface of the water toward the end of summer. After the rice is “knocked” into the canoes, it must be dried, parched, hulled, winnowed, and finished—a process that can span another month or more of work.

The wild rice harvest is a community event that maintains long-enduring relationships between Ojibwe people, their environment, and their foodways. In recent years, the PK-8 Lac du Flambeau Public School has included wild rice harvesting in its curriculum, bringing Native middle-school students out onto the rice beds, along with teachers, elders, and—most recently—University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW) folklorists. By bringing the harvest tradition into the school, educators seed a colonial western institution with indigenous cultural practice. Students are shown that the harvesting of wild rice is an important element of their Ojibwe identity, worthy of inclusion in their schooling.

With this article and the accompanying short film (Birchbark Canoes and Wild Rice) we examine the Lac du Flambeau wild rice harvest within the context of educational sovereignty and as a decolonizing educational initiative. As Luis Moll asserts:

Educational sovereignty requires that communities with assistance, with affiliations, create their own infrastructures for development including mechanisms for the education of children that capitalize on rather than devalue cultural resources. It will then be their initiative to invite others, including those in the academic community (2002, np).

His points are matched by those of Jamila Lyiscott (2016), who warns against top-down or outsider-to-insider curricula or programming that unintentionally replicate colonial messages of dependency and lack. As she writes, “The idea of ‘giving’ students voice, especially when it refers to students of color, only serves to reify the dynamic of paternalism that renders Black and Brown students voiceless until some salvific external force gifts them with the privilege to speak” (2016, np).

In this article we explore some productive ways in which folklorists can support or enhance educational sovereignty occurring in communities. We detail the role of UW folklorists at Lac du Flambeau Public School—our work in grant writing, project implementation, and ethnographic documentation, and in the broader process of establishing a culturally responsive curriculum. Embracing the principles of educational sovereignty, community-initiated and community-directed projects, participatory action research (Kemmis and McTaggart 2000, Westfall et al. 2006, Stringer 2013), indigenous-centered research (Tuhiwai Smith 1999), and the work of folklorists who have striven to make a place for local culture in school, museum, and community education settings (Simons 1990, Bowman 2004, Gay 2010, Bowman and Hamer 2011), we believe that folklorists have important roles to play in supporting such curricular innovations.

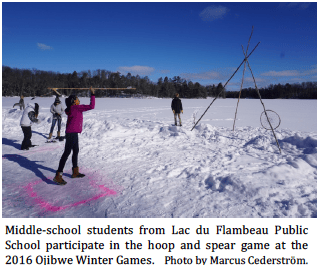

Our team of UW-Madison folklorists first began extended collaboration with the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians through an effort to revitalize competitive wintertime games and sports, called Ojibweg Bibooni-Ataadiiwin [The Ojibwe Winter Games]. This annual program, initiated and carried out by Ojibwe artist and educator Mino-Giizhig (Wayne Valliere), repatriates traditional competitions that were actively discouraged or prohibited during the missionary era and thus lost to the Lac du Flambeau community for over a century. We began documenting the community-driven work at the Reservation and pulled on our boots and gloves to lend a hand in the efforts. Our support included grant writing and fundraising, aiding on-the-ground project work, organizing related events at Lac du Flambeau and in Madison, shaping materials to share with media outlets, creating a web presence through social media, helping harvest natural materials, and assisting in construction of equipment. We have documented and helped curate programs for both students and general audiences that clarify and explain the importance of decolonization. And we have contributed to longstanding discussions in the community about how cultural revitalization works and to what ends it may lead. Multi-year collaboration with the Lac du Flambeau community on the winter games repatriation has let us test and appreciate the efficacy of cultural responsiveness in education, the subtle processes by which effective revitalization movements take shape, and the sometimes challenging steps needed to transform theoretical principles of decolonization into concrete practice.

Our team of UW-Madison folklorists first began extended collaboration with the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians through an effort to revitalize competitive wintertime games and sports, called Ojibweg Bibooni-Ataadiiwin [The Ojibwe Winter Games]. This annual program, initiated and carried out by Ojibwe artist and educator Mino-Giizhig (Wayne Valliere), repatriates traditional competitions that were actively discouraged or prohibited during the missionary era and thus lost to the Lac du Flambeau community for over a century. We began documenting the community-driven work at the Reservation and pulled on our boots and gloves to lend a hand in the efforts. Our support included grant writing and fundraising, aiding on-the-ground project work, organizing related events at Lac du Flambeau and in Madison, shaping materials to share with media outlets, creating a web presence through social media, helping harvest natural materials, and assisting in construction of equipment. We have documented and helped curate programs for both students and general audiences that clarify and explain the importance of decolonization. And we have contributed to longstanding discussions in the community about how cultural revitalization works and to what ends it may lead. Multi-year collaboration with the Lac du Flambeau community on the winter games repatriation has let us test and appreciate the efficacy of cultural responsiveness in education, the subtle processes by which effective revitalization movements take shape, and the sometimes challenging steps needed to transform theoretical principles of decolonization into concrete practice.

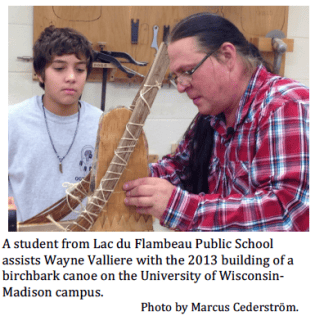

In the fall semester of 2013, building on these previous successes, our team arranged for Wayne Valliere to visit the UW campus as artist in residence in the woodshop of the university’s Art Department to construct a birchbark canoe. We were fortunate to work with the department’s chair, Tom Loeser, who was enthusiastic about exposing his students to Ojibwe arts and helped with fundraising and day-to-day coordination of the residency. Our project, “Wiigwaasi-Jiimaan: These Canoes Carry Culture,” afforded Valliere a venue for calling attention to the nuanced and demanding art of birchbark canoe building—a tradition currently practiced in Wisconsin by only three Native artists, all over age 50. Crucial to the project was the involvement of middle-school students from Lac du Flambeau, who harvested natural materials on the Reservation and in the ceded territories of northern Wisconsin and traveled over 200 miles south to the UW campus to assist in the canoe’s construction. Their visits not only helped demonstrate the value of Native cultures to university professionals and the wider university community, but also suggested to the visiting students that they can attend a university and maintain their Ojibwe identity. Through further fundraising, the team was instrumental in purchasing the resulting canoe for permanent exhibition and use at the university. The canoe is now displayed in the dining hall of Dejope Residence Hall, a dormitory designed to celebrate the Native American heritage of Wisconsin. In the spring of 2014, the UW team brought the canoe back to the Reservation to be honored and launched in front of the entire student body of the school and community members of Lac du Flambeau.

In the fall semester of 2013, building on these previous successes, our team arranged for Wayne Valliere to visit the UW campus as artist in residence in the woodshop of the university’s Art Department to construct a birchbark canoe. We were fortunate to work with the department’s chair, Tom Loeser, who was enthusiastic about exposing his students to Ojibwe arts and helped with fundraising and day-to-day coordination of the residency. Our project, “Wiigwaasi-Jiimaan: These Canoes Carry Culture,” afforded Valliere a venue for calling attention to the nuanced and demanding art of birchbark canoe building—a tradition currently practiced in Wisconsin by only three Native artists, all over age 50. Crucial to the project was the involvement of middle-school students from Lac du Flambeau, who harvested natural materials on the Reservation and in the ceded territories of northern Wisconsin and traveled over 200 miles south to the UW campus to assist in the canoe’s construction. Their visits not only helped demonstrate the value of Native cultures to university professionals and the wider university community, but also suggested to the visiting students that they can attend a university and maintain their Ojibwe identity. Through further fundraising, the team was instrumental in purchasing the resulting canoe for permanent exhibition and use at the university. The canoe is now displayed in the dining hall of Dejope Residence Hall, a dormitory designed to celebrate the Native American heritage of Wisconsin. In the spring of 2014, the UW team brought the canoe back to the Reservation to be honored and launched in front of the entire student body of the school and community members of Lac du Flambeau.

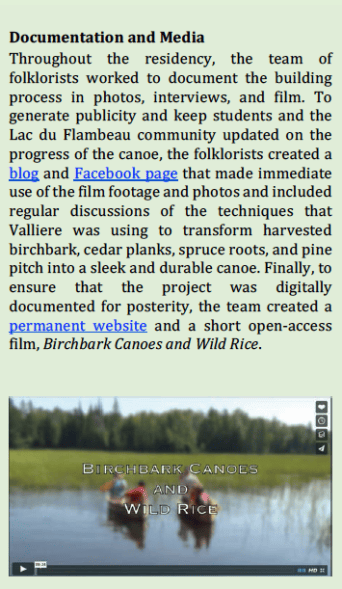

As a direct result of the publicity and enthusiasm generated by this canoe project, administrators at Lac du Flambeau Public School invited Valliere to build another canoe, this time at the school. That project, which unfolded over the academic year 2014-15, helped expand support among school officials to make Ojibwe culture and knowledge traditions (epistemologies) a central element of the curriculum for all its students, some 98 percent of whom are Native American. Together the films, blog, social media pages, websites, and the current article illustrate the kinds of materials that folklorists can produce to further support other professionals committed to decolonizing education in academia, museums, and PK-12 schools.

The Rice Harvest of 2015

Top: Wild rice after the 2015 harvest. Bottom: The birchbark canoe displayed in Dejope Hall on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, Spring 2014.

With the above-mentioned events as background, we turn now to the school rice harvest of 2015. One sunny morning in September, some 40 students, educators, and folklorists converged at a Wisconsin lake to harvest wild rice. On that shore, students put on life jackets and helped unload 16 school-owned canoes from trailers. The two birchbark canoes described above stood ready for the harvest as well. Central to our combined efforts has been the production and use of such canoes, not simply as pieces of art to be conserved and admired, but also as useful elements of daily life. The decision to employ the canoes in ricing also underscored the traditional use of such boats as vehicles for gathering and harvesting food, a notion quietly suggested to UW students by displaying the canoe in a dining hall instead of in the UW boathouse or art museum.

Standing on the shore, Valliere gestured toward the water, explaining:

A lot of you know what manoominikewin [wild rice harvesting] is, know what a manoominikaang is, a rice bed…. You guys have been exposed to this, a lot of you, through your families. Those of you that haven’t—that’s why we’re out here, we’re out here for you that haven’t. Manoomin, wild rice, is the single most important reason why the Anishinaabe are here where we’re at (2015).

As both a teacher and a cultural leader, Valliere underscored the Ojibwe understanding of plants and animals as “older brothers,” teachers, and allies. One by one, the adults helped students into canoes and launched them into the rice bed, while Wayne and his son Wayne, Jr., an aspiring educator, piloted the two birchbark canoes.

Top: Wayne Valliere teaching students the importance of wild rice in Ojibwe culture, September 2015. Bottom: Students from Lac du Flambeau Public School launch canoes into lake for the 2015 wild rice harvest. Photos by T. DuBois and Marcus Cederström.

It should be noted that heritage repatriation and educational sovereignty efforts at Lac du Flambeau did not begin with this partnership. In fact, the school has long supported students’ participation in traditional cultural activities. Even as pressure to standardize education and “teach to the test” have increased nationally, Lac du Flambeau Public School has remained committed to, and in fact intensified its investment in, culturally responsive education. After the day of ricing, in a community room at the school where elders and students can interact, Lac du Flambeau elder and teacher Carol Amour explained:

If you see your culture in your school, if you see your culture in your curriculum, if you see your culture valued, if you see your culture around you, it says to you, “My culture is important.” And it says, then, to you, “I have value. I am of worth” (2015).

By all accounts, the school’s culturally responsive curriculum has paid great dividends. Amour notes improved confidence and poise among students at the school, a markedly higher high school graduation rate, and an impressive increase in the number of students going on to college. As Amour puts it:

I think particularly for Native students, you’re dealing with that whole history of colonization and cultural genocide, and historical trauma. It’s there. To consciously and intentionally say, “No, that was not a good thing, there were many very negative things that happened, but we’re going to say that we’re taking charge. And we’re doing it in a Native way” (2015).

The film accompanying this article conveys some of the excitement and satisfaction that the harvest engendered among its participants, students and educators, young and old alike. Drafts of the film were shared with our Lac du Flambeau partners during production, and their input and ultimate endorsement of the final product were essential to our collaboration and eventual presentation of the film.

The view inside the birchbark canoe after bending the ribs. Photo by Colin Connors.

The longstanding engagement of American folklorists and other ethnographers with Native American communities has taken many turns. At the founding of the American Folklore Society in 1888, and under the energetic leadership of Franz Boas, folklorists working in communities reeling from the devastating effects of settler colonialism acquired, catalogued, and archived narrative traditions, detailed descriptions of ways of living, items of material culture—both sacred and profane—and even human bodies. Museums became repositories of items alienated from their original contexts, employed often to buttress racist narratives regarding the primitiveness and exoticism of “vanishing” Native American cultures (Macdonald and Fyfe 1996, Pilcher and Vermeylen 2008, Macdonald 2006, Toelken 2003, Gradén 2013). Museums as well as zoos displayed indigenous people as exotica (Huhndorf 2001, Baglo 2011, Lehtola 2013), using indigenous people as spectacles to facilitate white self-reflection and reinforce social values about the roles of racial, indigenous, and ethnic minorities in relation to a dominant settler society. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 provided a legal framework for restoring to Native communities some of the goods and human remains that American museums had taken (Ridington and Hastings 1997, Toelken 2003, Welsch 2012). More recent efforts have worked to use museums and educational museum programming as tools to decolonize representations of indigenous people (Vermeylen and Pilcher 2009). Archived and published accounts of practices, as well as artifacts stored in museums, can become catalysts for decolonization when returned to Native communities in ways that facilitate their reappraisal, re-adoption, and revitalization.

While folklorists of the 19th century engaged in what they regarded as salvage ethnography, Native children of the same era were funneled into residential boarding schools of the type planned and promoted by Richard Henry Pratt to “kill the Indian to save the man.” Often with the ignorance, complicity, or even urging of academic ethnographers (as detailed by Ridington and Hastings 1997), boarding schools sought to separate Native children from their languages, cultures, and worldviews, “reprogramming” them to become diligent domestics and manual laborers to fill the workforce void created by African American emancipation. Pratt’s infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School was replicated throughout the United States, and boarding schools remained a norm of education for reservation children from the 1870s until the 1970s, when at last the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 provided a framework for dismantling the system and restoring some measure of local control to Native communities (Child 1998). Despite the closure of such schools, the legacy of schooling as assimilatory and colonial has continued. Tribal members are often subjected to curricular materials that extol Columbus, rationalize settler enterprise, promote simplistic stereotypes of Native Americans, and sidestep unsavory details of relations between the U.S. and sovereign Native nations. Many Native parents rightfully worry that schools will undermine their children’s Native identity and lead them away from their community’s traditional lifeways.

Educators like Carter G. Woodson have long pointed out that American schooling has often worked to serve the goals of assimilation, social control, and deculturation (Bowman and Hamer 2011, 7), goals stated or implicit in the writings of early luminaries of public education such as John Dewey (1916). Through curricular choices, some culturally specific forms of knowledge and knowledge traditions, pedagogical methods, and worldviews find reinforcement while others are marginalized or rejected. Ojibwe forms have decidedly not been among those privileged. When no effort is made to “challenge the legacy of control and impositions” (Moll 2002, np) that actively work against indigenous communities, schools continue to serve as vehicles for imposed cultural assimilation. Heritage repatriation, the revitalization and strengthening of knowledge traditions and cultural worldview, and educational self-determination work in tandem to create sovereignty in indigenous schools.

As scholars like Geneva Gay (2002), Paddy Bowman (2004), and Elizabeth Simons (1990) have shown, culturally responsive education can help communities challenge and defeat imposed marginalization of local traditions and identities. Many studies have linked culturally responsive curricula to successful educational outcomes, particularly in Native American and other ethnic minority populations (Crooks et al. 2015; Neblett, Rivas-Drake, and Umaña-Taylor 2012; Phinney 1993; the Office of Head Start 2012). Such is not to suggest that the development of culturally responsive curricula is always easy or popular. Some programs rooted in vernacular cultures prove effective while others flounder. Teachers, however enthusiastic in principle, may lack the cultural knowledge or training needed to present materials or ideas from knowledge traditions radically different from their own. They may fear to ask what they do not know or remain uncomfortably silent, stances that do no favors for their students. Consciously or unconsciously, teachers and the curricula they present may reinforce attitudes that Native ways are outdated, inferior, or unwelcome in the classroom.

Moving Forward in a Good Way

In reflecting on the Lac du Flambeau-UW collaboration in relation to educational sovereignty, we point to four specific factors that we believe contributed to its success. Our first observation underscores the importance of local leadership and innovation in ensuring the initial, as well as the sustained, success of programs. The programs discussed here were designed by Lac du Flambeau educators to make their community stronger and healthier. There are noteworthy parallels on other reservations and in other tribal contexts in Wisconsin: for example, a hundred miles to the west, the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians have included Ojibwe traditions in their elementary school curriculum as well as at the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College (McGrath 1995, Anon. 2008). Lac Courte Oreilles’s community college is paralleled by that of the College of Menominee Nation, some hundred miles to the southeast of Lac du Flambeau on the Menominee Reservation. While such programs can serve as inspirations, crucial for the success of the Lac du Flambeau curriculum has been the active engagement and leadership of Lac du Flambeau educators as they highlight, celebrate, and sustain Ojibwe traditions. Year upon year, these programs demonstrate their effectiveness to community members, underscoring the need to continue, improve, and expand them in the future. Their momentum derives from the community that initiates and enacts them.

In reflecting on the Lac du Flambeau-UW collaboration in relation to educational sovereignty, we point to four specific factors that we believe contributed to its success. Our first observation underscores the importance of local leadership and innovation in ensuring the initial, as well as the sustained, success of programs. The programs discussed here were designed by Lac du Flambeau educators to make their community stronger and healthier. There are noteworthy parallels on other reservations and in other tribal contexts in Wisconsin: for example, a hundred miles to the west, the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians have included Ojibwe traditions in their elementary school curriculum as well as at the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College (McGrath 1995, Anon. 2008). Lac Courte Oreilles’s community college is paralleled by that of the College of Menominee Nation, some hundred miles to the southeast of Lac du Flambeau on the Menominee Reservation. While such programs can serve as inspirations, crucial for the success of the Lac du Flambeau curriculum has been the active engagement and leadership of Lac du Flambeau educators as they highlight, celebrate, and sustain Ojibwe traditions. Year upon year, these programs demonstrate their effectiveness to community members, underscoring the need to continue, improve, and expand them in the future. Their momentum derives from the community that initiates and enacts them.

We suggest that this type of community engagement is essential. In a context in which Native communities have been subjected to the dictates of outside managers for centuries, a project initiated by outsiders without local leadership is destined to be viewed with suspicion, if not also resentment. As Amour put it, “It isn’t someone non-Native coming in and telling us how to do it, or we should do this or we should do that. It is us—this Cultural Connections team—and it’s almost all Native now. That’s powerful” (2015). As a direct result of this local approach, elders, teachers, school administrators—and most importantly parents and students—have been supportive of and enthusiastic about experiential learning opportunities.

We suggest that this type of community engagement is essential. In a context in which Native communities have been subjected to the dictates of outside managers for centuries, a project initiated by outsiders without local leadership is destined to be viewed with suspicion, if not also resentment. As Amour put it, “It isn’t someone non-Native coming in and telling us how to do it, or we should do this or we should do that. It is us—this Cultural Connections team—and it’s almost all Native now. That’s powerful” (2015). As a direct result of this local approach, elders, teachers, school administrators—and most importantly parents and students—have been supportive of and enthusiastic about experiential learning opportunities.

Secondly, we suggest that cultural projects are more effective when educators embrace Native pedagogies that enact rather than describe culture. According to Valliere (2015), “There is a difference between teaching the culture, and teaching culturally. The latter is what I try to do.” It requires or empowers educators to embrace Native knowledge traditions and to be prepared to challenge or augment western approaches to education. Embodied and experiential learning has proven effective in situations where “traditional schooling” is ineffective (Gee 2004). This enactment is essential in building a successful culturally responsive program. “It’s not enough to know your culture,” Valliere points out, “You have to live it.” Amour, reflecting on the students’ harvesting manoomin with their teachers and elders, says:

That was phenomenal this morning to see the [non-Native] teachers go out with the kids, which says, without saying a word, of course…“We think this is important. And, we’re all teachers and we’re all learners. Today we’re learning from you. Going out [ricing], we’re learning from you” (2015).

Thirdly, as is evident in Amour’s words above, we suggest that outside organizations and individuals must support and respect the decisions of local leadership, or, as Luis Moll says, embrace “the need to challenge the arbitrary authority of the power structure to determine the essence of the educational experience” (2002, np). In the view of educators like Valliere and Amour, frameworks that replicate—however well meaning—outside institutional control and evaluation carry with them powerful and corrosive underlying messages of dependency, backwardness, and ignorance. To counter this potential, and acknowledge the leadership as well as the cooperation essential in our collaboration, the UW and Lac du Flambeau partners have worked to make explicit their understandings of mutual interests: in other words, folklorists and community members have stated clearly their professional goals and worked to enact procedures that serve to meet the needs of all parties.

A shared understanding of explicitly stated goals allowed partners to assist each other’s efforts effectively. Understanding that Lac du Flambeau educators valued the opportunity for their students to see the UW campus and form positive impressions of potential life and study there, UW folklorists made sure to show visiting students dorm rooms, art facilities, classrooms, and other parts of campus. Understanding the UW folklorists’ interest in sharing Ojibwe culture with a broad university community, Valliere participated actively in a wide array of educational events and classes across campus, making a point as well of talking with every visitor who came to the university woodshop to see his work. Where visitors may have expected to find an artist in residence working in isolation—a modern-day equivalent of the kind of museum and zoo displays of indigenous people of the past—they found instead an outgoing artist, interested in the fields they represented, eager to make new allies who could help realize his educational vision for his community, and encouraging of others to lend a hand in the hard work of the canoe’s construction and his community’s decolonization.

Finally, we note that funding frameworks tend to favor short-term projects that result in easily quantifiable products and measurable results, but within the framework of a school, a project that occurs only once and is not repeated may frustrate or disappoint participating teachers, students, and families. Decolonization efforts demand continued reinvestment and crosspollination across traditional lifeways to help ensure viability and lasting outcomes. Our collaboration benefits greatly from a multi-year approach and includes various, separately funded stages that all center around key personnel—specifically, local educators—and shared goals of decolonization and educational sovereignty. Our aim was to build a responsive and adaptable partnership that allows educators to replicate an existing program, encourages artists to move on to new challenges, presents funders with exciting new projects within the framework of the partnership, and—most importantly—grows community capacity to take full ownership over any work that folklorists helped catalyze. We feel that it is counter to the very notion of educational sovereignty and decolonization to mandate the involvement of outsiders in every future cultural project in Lac du Flambeau and that building cultural sustainability and educational sovereignty necessarily means our relationships to the community as public folklorists must change.

The four points outlined above helped advance the educational sovereignty and decolonization efforts in Lac du Flambeau. Over the course of several years, we have come to see firsthand the obvious benefits that such a program has for a community and a school. The value of incorporating programs of the kind described here into school and museum curricula and the role of folklorists in support of this work cannot be underestimated. Successful projects must acknowledge that the past shapes the present as well as the future and that educators, in collaboration with communities, can and must recontextualize traditional knowledge for the benefit of students. In Native communities, young people have often endured the strains and uncertainty of negotiating two separate structures of authority: that of local elders and cultural leaders and that of western educational representatives. Native people are often forced to choose which authority they might respect or invoke in any given moment. By providing situated programs through the public school, with the logistical support and cultural endorsement of UW folklorists, the projects gained legitimacy and promoted an overarching Ojibwe-centered educational approach. Instead of competing against each other, the two systems of knowledge authority worked in tandem. Together we are shaping a curricular context in which traditional knowledge can be used, helping it thrive in the community and in the school. As Valliere puts it in describing the value of these projects to students:

By them having identity and knowing who they are, there’s an old, old motif for their people: it’s like this, “By knowing where you’ve been, you’ll have a greater understanding on where you’re going.” So, it’s going to add strength, that solid foundation of their identity is going to [make them say], “Yes, I can go to college. I can obtain that education. But I don’t have to lose my Native value to understand Western society and be part of it. I can be the best of both worlds” (2014).

Carol Amour echoes those sentiments: “To me, it’s so obvious that it’s good for kids. And that this way of teaching is good for our kids in this community” (2015).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Carol Amour, Leon Valliere, Wayne Valliere, Wayne Valliere, Jr., Doreen Wawronowicz, and all the students from Lac du Flambeau Public School. They are the reason that these projects have been successful. We are honored to have been invited to work with them and support their efforts. Thanks also to the many community members in Lac du Flambeau and Madison who have given so generously. Finally, thanks to the many different organizations and individuals who have sponsored and supported these projects. For a complete list of supporters please visit go.wisc.edu/canoe.

Marcus Cederström is a PhD candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in Scandinavian Studies and Folklore. His research focuses on Scandinavian immigration to the United States, identity formation, North American indigenous communities, and sustainability.

Thomas A. DuBois is the Halls-Bascom Professor of Scandinavian Studies and Folklore at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. With a PhD in Folklore and Folklife from the University of Pennsylvania, he has taught at both the University of Washington and the University of Wisconsin.

Tim Frandy, PhD, is a folklorist and an Assistant Professor of Native American and Indigenous Studies at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin. His research focuses on ecological worldview, traditional ecological knowledge and land-use traditions, the medical humanities, and northern indigenous communities. He has also published on shamanism, traditional healing, activist movements, and the digital humanities.

Colin Gioia Connors is a PhD candidate in Scandinavian Studies and Folklore at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He has a background in landscape archaeology and Old Norse Studies.

Works Cited

Anon. “LCO Honors Founders at 25th Anniversary Event.” Tribal College Journal of American Indian Higher Education. August 15, 2008.

Amour, Carol. 2015. Personal interview. September 4. Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin.

Baglo, Cathrine. 2011. “På ville veger? Levende utstillinger av Samer i Europa og Amerika.” Tromsø: University of Tromsø.

Bowman, Paddy B. 2004. “’Oh, that’s just folklore’: Valuing the Ordinary as an Extraordinary Teaching Tool.” Language Arts 81.5: 385-395.

Bowman, Paddy and Lynne Hamer. 2011. Through the Schoolhouse Door: Folklore, Community, Curriculum. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Child, Brenda J. 1998. Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Crooks, Claire V., Dawn Burleigh, Angela Snowshoe, Andrea Lapp, Ray Hughes, and Ashley Sisco. 2015. “A Case Study of Culturally Relevant School-Based Programming for First Nations Youth: Improved Relationships, Confidence and Leadership, and School Success.” Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 8.4: 216-230.

Dewey, John. 1916. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Gay, Geneva. 2002. “Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching.” Journal of Teacher Education. 53.2: 106-116.

___ . 2010. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gee, James Paul. 2004. Situated Language and Learning: A Critique of Traditional Schooling. New York: Routledge.

Gradén, Lizette. 2013. “Performing Nordic Spaces in American Museums: Gift Exchange, Volunteerism and Curatorial Practice,” in Performing Nordic Heritage: Everyday Practices and Institutional Culture, eds. Peter Aronson and Lizette Gradén. Farnham: Ashgate, 189-220.

Huhndorf, Shari M. 2001. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kemmis, Steven and Robin McTaggart. 2000. “Participatory Action Research,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds. Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 567-605.

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka. 2013. “Sámi on the Stages and in the Zoos of Europe.” L’Image du Sápmi II. Études comparées. Göteborg: Humanistic Studies at Örebro University.

Loew, Patty. 2013. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Lyiscott, Jamila. 2016. “If You Think You’re Giving Students of Color a Voice, Get Over Yourself.” Black(ness) in Bold: Black Professors, Black Experiences and Black Magic, accessed March 29, 2016, https://blackprofessorblog.wordpress.com/2016/03/25/if-you-think-youre-giving-students-of-color-a-voice-get-over-yourself.

Macdonald, Sharon and Gordon Fyfe. 1996. Theorizing Museums. London: Blackwell.

Macdonald, Sharon, ed. 2006. A Companion to Museum Studies. London: Blackwell.

McGrath, David. 1995. “Lac Court Oreilles Ojibwa Community College: The Little Northwoods School with a Giant Task.” Contemporary Education. 67.1: 21-25.

Moll, Luis. 2002. Keynote Address at the University of Pennsylvania. “The Concept of Educational Sovereignty.” Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education. 1.2: 1–11.

Neblett, Enrique W., Deborah Rivas-Drake, and Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor. 2012. “The Promise of Racial and Ethnic Protective Factors in Promoting Ethnic Minority Youth Development.” Child Development Perspectives. 6.3: 295-303.

Office of Head Start. 2012. Tribal Language Report, accessed April 15, 2015, http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/states/aian/pdf/ohs-tribal-language-report-jan-2012.pdf.

Phinney, Jean S. 1993. “A Three-Stage Model of Ethnic Identity Development in Adolescence,” in Ethnic Identity: Formation and Transmission among Hispanics and Other Minorities, eds. Martha E. Bernal and George P. Knights. Albany: State University of New York Press, 61-79.

Pilcher, Jeremy and Saskia Vermeylen. 2008. “From Loss of Objects to Recovery of Meanings: Online Museums and Indigenous Cultural Heritage.” M/C Journal. 11.6.

Ridington, Robin and Dennis Hastings (In’aska). 1997. Blessing for a Long Time: The Sacred Pole of the Omaha Tribe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Simons, Elizabeth Radin. 1990. Student Worlds, Student Words: Teaching Writing through Folklore. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook.

Stringer, Ernest T. 2013. Action Research in Education. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Toelken, Barre. 2003. The Anguish of Snails: Native American Folklore in the West. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

Valliere, Wayne (Mino-Giizhig). 2014. Personal interview. February 20. Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin.

. 2015. Personal interview. September 4. Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin.

Vermeylen, Saskia and Jeremy Pilcher. 2009. “Let the Objects Speak: Online Museums and Indigenous Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Intangible Heritage. 4: 60-78.

Welsch, Roger. 2012. Embracing Fry Bread: Confessions of a Wannabe. Lincoln: Bison Books.

Westfall, John M., Rebecca F. VanVorst, Deborah S. Main, and Carol Herbert. 2006. “Community-Based Participatory Research in Practice-Based Research Networks.” Annals of Family Medicine. 4.1: 8-14.

URLS

https://ldfwintergames.wordpress.com

https://www.facebook.com/ojibwegbibooniataadiiwin

https://wiigwaasijiimaan.wordpress.com

https://www.facebook.com/Wiigwaasi-Jiimaan-These-Canoes-Carry-Culture-398037316986232

https://www.housing.wisc.edu/residencehalls-halls-dejope.htm