Photo of Bayman Reid Riemer by Nancy Solomon.

In Fall 2012, Superstorm Sandy struck Long Island, New York, and was one of the worst hurricanes ever to strike the region. The folklife nonprofit Long Island Traditions, with the assistance of a National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Preserve America Grant, implemented a maritime traditions documentation project in the Freeport School District during the 2015-16 school year. The project looked at how Superstorm Sandy affected the seafaring community, its residents, and its maritime traditions. Freeport is a diverse community of recent immigrants and established residents. Many students were displaced into alternative schools and homes following Sandy because Freeport was one of the hardest hit communities on Long Island. As a result, the fishermen could relate to the challenges that the students faced after Sandy.

We chose to design our project with teachers so that they and their students could share their experiences with the fishermen, who were also devastated by the storm. The goal was to examine the history of this waterfront community through the eyes of tradition bearers—fishermen, baymen, boat builders, and decoy carvers—who learned these traditions within their families and communities. Freeport was once home to dozens of maritime tradition bearers who harvested finfish and shellfish in the western bays of Nassau County, using traditional rakes, nets, and flat-bottom boats. They harvested clams, oysters, menhaden, fluke, flounder, eels, and other species.

After World War II, recreational fishing became a major industry for fishermen and baymen, who harvested bait fish for the new recreational sportsmen. Although new regulations affected the commercial fishing industry, an active group of fulltime commercial fishermen worked until Superstorm Sandy.

Long Island Traditions began our school programs in the district in 1988 to bring students, their families, and the community together. Since then, we have featured master maritime tradition bearers identified by our staff and consulting folklorists through fieldwork that began in 1987 and continues. Fieldtrips to the commercial fishing district and maritime educational tours for the general public helped bridge the geographic and informational gap between waterfront residents and school-age families.

Our program has provided important opportunities for traditional fishermen to teach students in their communities about the ecological changes in Freeport, based on their personal observations over decades of experience. Through interviews, hands-on workshops, and fieldtrips with local fishermen, students came to understand how the traditions of commercial fishermen and baymen changed over time. After Sandy, many of our longtime program participants were unable to work with us because of the closure of the bays and the need to restore their severely damaged homes, docks, and boats. Thus, we began this new project in Fall 2015—with substantial funding and support from the school district—to incorporate stories of Sandy and the effects of this disaster.

The last few years before the storm we caught plenty of fish. After the storm it was a living nightmare. Besides the waters being closed for clamming, you couldn’t even drive through town; there were boats in the road everywhere. It was devastation everywhere. —Joey Scavone, Commercial Fisherman, Freeport. Photo of Freeport during Sandy by Ben Jackson.

Fifteen 4th-grade classes with 700 students from three elementary schools participated. Many came from established African American families and Latino families who were first-generation Americans. We began with a planning meeting that all participating teachers attended to discuss potential student projects, curriculum approaches, tradition bearers, and resources. As people who experienced the storm, we felt the program should respond to teachers’ perspectives on how Freeporters survived and coped with the storm. The teachers suggested creating a maritime magazine with a variety of writings, including stories that Long Island Traditions had collected from storm survivors, photographs of the tradition bearers at work, and vocabulary terms commonly used by the tradition bearers.

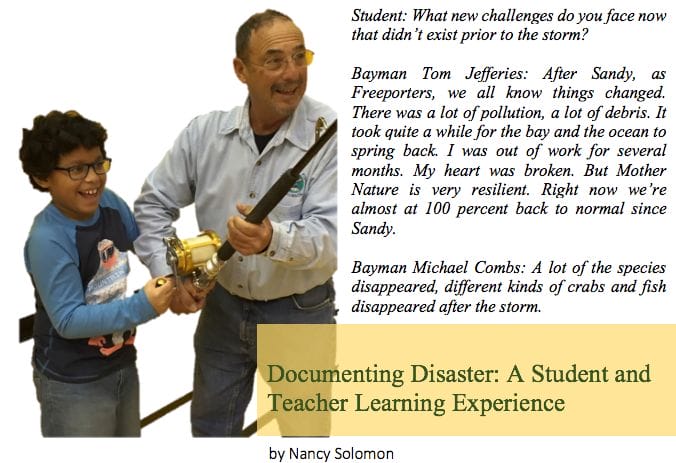

Teachers and school staff, including the librarian and curriculum specialists, decided to begin with two class presentations by baymen Tom Jefferies and Michael Combs of Freeport. Both suffered from Superstorm Sandy on a personal and an occupational level. Using photographs, the two discussed their harvesting activities, their backgrounds, and how Superstorm Sandy affected their occupational culture. The photographs came from Long Island Traditions fieldwork journeys with each of the baymen prior to and after Sandy and from public archival collections including NOAA and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). After asking questions of the baymen, students shared their own experiences of Sandy. Next, students recorded interviews with Tom and Michael that became the basis for a video production. They had developed questions beforehand and conducted the interview using an iPad and a microphone. Questions focused on occupational experiences, Superstorm Sandy, and changes in the bay.

The second project component was a hands-on workshop the week following the baymen’s presentations. There were also 20-minute interview sessions with more tradition bearers on creating a traditional maritime object or using a traditional skill such as net mending, trap building, and decoy carving. Students conducted interviews with 12 tradition bearers during the workshop. Students were split into small groups, allowing for personal interactions with participants, including commercial fishermen who worked inshore and offshore, decoy carvers, boat builders, model makers, net menders, and trap fishermen. Students recorded interviews with the fishermen during the workshop and in the school library. One teacher worked with the students to produce a finished video based on their interviews and research.

Since fishing in the winter is severely limited in the mid-Atlantic, these school-based activities took place in the winter months when tradition bearers are more available. In addition, schools have more time for extended school residencies such as this one, enabling us to offer an immersive experience. The project also helped teachers prepare their students for English Language Arts exams by offering engaging alternative written materials reflecting local culture other than those typically used for test preparation. One alternative resource we provided was Maritime Magazine, a student-oriented collaboration between our staff and the teachers. The magazine features first-person narratives that we collected, photographs, drawings, and a glossary of common local maritime terms.

The final program element was a fishing trip onboard the Miss Freeport, a charter boat that specializes in educational experiences. Students learned to fish in the bay and near the inlet. Additionally they developed knowledge about the different species in each habitat location, changes to the habitat since Sandy, and different kinds of bait. For many this was their first time fishing or being on a fishing boat. Students and their teachers documented the trip through video that was incorporated into the final production.

To edit a final video, teachers first asked students to identify passages in their recordings that had special significance to them. These generally fell into the categories of occupational culture and storm experiences. Students worked in groups and reached consensus on the final excerpts. They also worked with one of the classroom teachers who had special training in school-based film production to develop an engaging video, A Time for Change, which highlighted their experiences as well as the knowledge of the tradition bearers.

View A Time for Change, a grade-wide presentation of the video was the culminating element of the program at the end of the school year.

In 2017, Long Island Traditions produced an exhibit about storms and hurricanes, In Harm’s Way. Professionally produced videos using our archival materials accompanied it. One video examined fishermen’s experiences during Sandy and became part of the curriculum for the 2018 program. The eight-minute film featured fishermen from the South Shore of Long Island, where the storm hit hardest, and included segments from inshore and offshore fishermen.1 This year the video introduced new students to the project and served as a starting point to develop questions for tradition bearers, for example: Where are their boats docked? What are challenges to their occupation? And, which skills helped them before and after Sandy?

In 2017, Long Island Traditions produced an exhibit about storms and hurricanes, In Harm’s Way. Professionally produced videos using our archival materials accompanied it. One video examined fishermen’s experiences during Sandy and became part of the curriculum for the 2018 program. The eight-minute film featured fishermen from the South Shore of Long Island, where the storm hit hardest, and included segments from inshore and offshore fishermen.1 This year the video introduced new students to the project and served as a starting point to develop questions for tradition bearers, for example: Where are their boats docked? What are challenges to their occupation? And, which skills helped them before and after Sandy?

This project was feasible because of our longstanding relationship with the school, the students, their teachers, and the fishermen. Since 1987, we have been working with the school district and local tradition bearers. We had long-established relationships prior to Sandy. As a result, we were able to conduct interviews within the community shortly after Superstorm Sandy. In addition, we had worked with the school district, so there was respect for our program and we could design this new project collaboratively. Enough time had passed since the storm that students and teachers were no longer coping with the immediate trauma of the storm, yet there were still important memories that could connect the participants to the event.

Other factors helped. We had robust funding from a variety of sources, including NOAA, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the school district. In addition, the school district allocated sufficient staff development time so that teachers could work directly with us in planning and executing the program. As noted earlier, the district also had technological resources to develop the multimedia materials, and each classroom had appropriate equipment to develop and present the materials that students created.

Tom Jefferies in the classroom. Photo by Nancy Solomon.

Student: What major lesson or underlining message can people learn from natural disasters such as Superstorm Sandy?

Bayman Tom Jefferies: I learned about myself and how I could spring back and rectify the situation, since so much did go wrong. You learn about your neighbors and friends and family. People who you never spoke to in the street would sometimes help you. You learn that there’s a lot of compassion.

Documenting disasters like Superstorm Sandy can be full of challenges and rewards to the community. Such programs provide a safe space where community members who have limited contact with one another can establish close relationships across many boundaries. The program helped participants learn from one another, in a multidisciplinary environment that encouraged reflection and creativity. By focusing on local ecological knowledge and occupational traditions, the project opened new doors and ways of looking at their community for all the participants. While we hope the ravages of natural disasters spare our hometowns, tornadoes, superstorms, and hurricanes unfortunately seem to be growing more common. We offer this program as an educational tool that may help people in other places cope.

Nancy Solomon received her MA in American and Folklife Studies from George Washington University. She is the Executive Director of Long Island Traditions, which is dedicated to documenting, presenting and preserving the architectural, ethnic, and occupational traditions of the region. She is curator of In Harm’s Way, author of several books and articles, and a columnist for Voices, a publication of the New York Folklore Society.

Endnotes

- The video can be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FIaUOTyj8Qo&index=3&list=PL_pPoNArok3uqIvl2V9IfJQl6HjyLPhOE.

URLS

Student film: https://youtu.be/FChSLCyVo9E

Student powerpoint: https://freeport.edu.buncee.com/buncee/aaa3ae4313cb4bfab01ae4a69174f947

In Harms Way: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FIaUOTyj8Qo&index=3&list=PL_pPoNArok3uqIvl2V9IfJQl6HjyLPhOE

Resources

FEMA Media Gallery https://www.fema.gov/media-library#{}

Long Island Studies Institute https://www.hofstra.edu/library/libspc/libspc_lisi_main.html

NOAA Image Gallery http://www.photolib.noaa.gov/index.html

NOAA Voices from the Fisheries https://www.voices.nmfs.noaa.gov

NOAA Voices from the Fisheries: LI Traditions Climate Change and Sandy Collection https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/apex/f?p=213:6:::NO:RP::

Freeport School District Project Video https://youtu.be/FChSLCyVo9E