Introduction

Introduction

In our work as educators, we strive to honor the vision shared with us by beloved Elders; each step we take in any direction offers an exceptional opportunity for learning; each step is an imprint of exploration leading us through a unique path of observation, curiosity, healing, and joy. This is the approach our Elders have taught us to take in education. While we might wander through some areas alone in quiet reflection, in other sections we walk together in shared exploration. In this project we are lucky to have also walked along with Ichishkíin language, and with our Elder, átway Tux̱ámshish* Dr. Virginia Beavert, for some time. Tux̱ámshish reminded us often that learning is reciprocal; while we will all always have more to learn from ourselves and others, we are also responsible to teach that which we have been privileged to learn.

Indigenous languages themselves are reciprocal caretakers of culture, holding and carrying the foundation of knowledge and being throughout generations (Hermes, Bang, and Marin 2012; Jacob 2013). Language and culture work together both to form and to sustain a unique worldview, one that Indigenous children have inherent rights to acquire and fully enjoy (Greenwood 2016, Hoffman 2021), alongside their rights to other life-sustaining entities such as water and air (Sutterlict 2022). Indigenous languages are intimately connected to place, and as such, a vital part of critical Indigenous pedagogies of place (Porter and Cristobal 2018).

In terms of language and its inextricable connection to culture, identity, rights, and place, Tux̱ámshish (Beavert 2017, 4) wrote, “My language means that I, my relatives, and tribal members are human…. The traditions and cultural heritage passed down by the Sahaptin people through generations identify our country and our inherent right to occupy our geographical place…We are its original inhabitants.” The language reflects this in the way it brings our attention through its form to different approaches and movements within traditional processes and practices–as these processes refine, so too does the language. She also emphasized the importance of immersing children in the language from an early age through speaking, laughing, and singing in their Indigenous language, so that “in this way the language never leaves the child.” In this way, “cultural rigor,” including Indigenous languages, “should be taught as the same level as academic rigor” (Topkok 2018, 101).

Ichishkíin is a critically endangered language with many dialects spoken in the Columbia River Plateau in parts of the Pacific Northwest now commonly called Washington and Oregon. Many people in many roles—parents, babies, youth, aunties, uncles, grandparents and greats, teachers, students, linguists, advocates, and allies—are engaging in efforts to preserve and strengthen Ichishkíin language use and cultural practices across Ichishkíin-speaking communities (Anderson 2022, Jansen 2010, Sutterlict 2022, Jacob 2013). Ichishkíin is taught in several community and academic contexts from infant programming to university levels. At the University of Oregon, three full years (nine quarters) of Ichishkíin language courses are offered each year with steps underway to offer a minor degree and support other Indigenous languages through further program development. Ichishkíin courses are designed to support community efforts of language cultivation through meaningful, practical, project-based curriculum and community connections designed to support daily language use (Anderson 2019).

Projects such as the one described here contribute to our ability to continue raising Yakama children with Ichishkíin, tending to their inherent rights and well-being, while also fostering our own growth. Language learning materials provide community members access to relationships and perspectives embedded in the language an an important form of cultural documentation. When we create with Elder mentors, our projects often document language and cultural nuances that have not yet been recorded and through this collaborative process, we can ask questions to further clarify our understanding of culture through language. Materials developed in community are shared back with parents, caretakers, teachers, and learners who are working to raise a new generation of first-language speakers while being heritage- or second-language learners themselves. This sharing allows us to continue refining our materials, too, with input and feedback that come from community engagement with created resources. Materials are not static but living documents with capacity for ongoing refinement through our continued conversations and learning. Resources such as these meet the direct requests of parents and caretakers (Anderson 2022, Igari et al. 2020, Sutterlict 2022) and offer footholds and support as we continue to step forward in growth and reciprocity.

Context of This Project

Our article discusses a collaborative project focused on strengthening Ichishkíin language revitalization and supporting the cultural knowledge and well-being of Indigenous teacher education students. This project is nested within the Sapsik’ʷałá Teacher Education Program (2024), a university graduate program focused on preparing highly qualified Indigenous K-12 teachers who go on to teach in Native-serving schools and communities. The Sapsik’ʷałá Program operates as a consortium with the nine federally recognized Tribal Nations in Oregon who each appoint educational representatives to serve on the program’s Tribal Advisory Council. Our consortium-based approach and Tribal Advisory Council model are designed to ensure the program is in relationship with and responsive to Tribal Nations’ needs and priorities. Preparing educators to teach and contribute to the revitalization of Indigenous languages has been a priority that Tribal Advisory Council members express consistently.

To support students in their process of becoming teachers, the Sapsik’ʷałá Program uses a cohort-based model in which Sapsik’ʷałá students participate in cohorts to discuss knowledge, skills, and problems of practice related to their specific grade levels and subject and licensure areas. Sapsik’ʷałá students also participate as a cohort-within-a-cohort and engage in an Indigenous community of practice focused specifically on their roles and responsibilities as Indigenous educators of Indigenous youth.

An Indigenous education seminar supports students in learning how to apply culturally sustaining/revitalizing (McCarty and Lee 2014) and Indigenous storywork pedagogies (Archibald 2008) in their classrooms. The seminar is also an intergenerational space in recognition that Elders and Elder pedagogies are invaluable and offer vital teachings that span generations, helping us connect to ancestral knowledges from the past and envision alternatives beyond our colonial present (Holmes and Tolbert 2020). We invited Elders to participate in the seminar and share their teachings related to language, culture, and teaching; we formalized this practice by creating a Distinguished Elder Education position (Jacob and Sabzalian 2022). One beloved átway Elder, Tuxámshish Dr. Virginia Beavert, generously served our program in this role and graciously shared her knowledge related to Ichishkíin language and culture with our students during class and through books she wrote documenting her upbringing and Yakama stories (Beavert 2017; Beavert, Jacob, and Jansen 2021). She routinely emphasized the importance of Indigenous languages and Indigenous kinship and encouraged our Indigenous educators to foreground both in their teaching.

Our Ichishkíin language project continues the legacy of Indigenous language work to which our beloved Elder dedicated her life and which Tribal partners consider urgent and important. The work to strengthen Indigenous language teaching and learning approaches in our programs is ongoing. Materials are consistently being created, shared, and used, often without the resources required to do multiple rounds of proofreading, editing, and public dissemination. More often, resources are developed by students and shared in their own families and with a smaller circle of peers. However, with modest grant funding, we were able to plan a project with a more ambitious dissemination approach to encourage more families and educators to use the resources to support their own goals for language learning and teaching. As such, the project can be viewed as an expression of research and teaching that is Tribally driven and accountable to Tribal priorities (Norman and Kalt 2015, 12). By using time and space within a university-based seminar to respond to the needs of Tribal communities and the urgency of language revitalization, we attempted to shift the relationship between the university and Tribal communities who speak Ichishkíin to be more respectful, responsive, collaborative, and reciprocal, which benefits Indigenous communities and languages, as well as university students (Norman and Kalt 2015).

We note, however, that this project also took place in a context with few institutional resources to support our goals. Those invested in Indigenous language revitalization often have scarce resources to support their work. As such, we discuss our language revitalization efforts through the concept and practice of making do, which at its core, means “to make something do what you want or need it to do” (Henn 2018, 161). Making do is a practice of doing the best you can with the resources available, and it often involves creatively using whatever is at your disposal in innovative or subversive ways to achieve your goals. Turning a bucket upside down to sit on if you need to rest, for example, is a strategy of making do (161). In contrast to a do-it-yourself (DIY) project in which you have time and resources available to make what you need, making do often involves subverting or creatively repurposing “a product’s official purpose so it may be of service to one who wishes to use it in a new way” (161), which, as Henn offers, is often “a creative practice born out of the constraints experienced by a producer” (162). Making do is a flexible, relational, dynamic, creative, strategic, and subversive process focused on creating (rather than purchasing) what we need, or repurposing public resources for personal (and, in this case, collective and Tribal) goals.

In many ways, our Sapsik’ʷałá Program reflects “the art and work of making do” by subverting and creatively repurposing a whitestream teacher education program to support Indigenous self-determination in education. Similarly, the Indigenous education seminar space foregrounds a pedagogy of making do by subverting the English and Eurocentric realm of “teacher knowledge” and infusing Indigenous languages and Elder pedagogies in class. The Ichishkíin language curriculum work also reflects a pedagogy of making do by using the pedagogical tools that have been weaponized against Indigenous communities—the written word, alphabets, or formal curriculum—and repurposing them to advance the goals of Ichishkíin language revitalization. Indeed, Indigenous language advocates and activists have a long history of making do, such as creating the alphabets, books, resources, or schools that do not exist, or repurposing the oppressive domain of federal policy to protect and promote Indigenous language revitalization (Lomawaima and McCarty 2025). As language education scholar Teresa L. McCarty reflects, Indigenous language work takes place on a political and intellectual landscape that is deeply shaped by settler colonialism and relations of power, “…yet this is the ground navigated every day by the people whose lifework makes the road by walking it” (Lomawaima and McCarty 2025, 13). By creating resources that do not yet exist, in this case an Ichishkíin language resource to support Ichishkíin language teaching and learning, the project we describe reflects the important work of making do and, in the context of Indigenous education, carving out zones of sovereignty to nurture Indigenous languages within Eurocentric and English-dominant educational spaces (Lomawaima and McCarty 2025).

Project Purpose and Examples

The purpose of the project was to create classroom-ready teaching resources to support Ichishkíin language education and revitalization. This curricular resource development project was designed to strengthen Indigenous self-determination in education. By engaging Elders, the project focused on strengthening relationships and collaborations that would not otherwise exist. Relational approaches to education are important within Indigenous communities, as emphasized by our átway Elder, who regularly reminded us of the importance of kinship in education (Jacob and Sabzalian 2022). The project was designed using an inductive approach engaging our Elder in a series of visits in summer 2023 (Tuck et al. 2022). Indigenous education honors the importance of seasons, and our calendar is traditionally understood as cyclical, with a seasonal round of harvesting and visiting in specific places and times throughout the year (Hoffman 2021, Jacob et al. 2018). Our project was conceptualized under these conditions, spending time in the summer visiting and dreaming of possibilities for our new cohort of students who would begin our seminar the following fall. As educators, we always look forward to the start of the new year. We love envisioning the promise and possibilities of a brand-new school year just beginning to unfold. Summertime is a fabulous time to dream of projects that can best fulfill our community needs while providing students with culturally grounded and sustaining skills and relationships. Our Elder shared the importance of visiting, kinship, and the need to share and “do something” about the survival of our languages. We kept these instructions close to our hearts and began planning the process we would use to develop the project. We planned to engage two groups of students who, because of the structure of the university, would not normally interact with each other: Indigenous teacher candidates (whose work in the project is the focus of our manuscript) and advanced Ichishkíin students (who served as peer mentors in the project).

In the fall, we introduced students to the project plan: Indigenous teacher candidates would learn the basics of Ichishkíin (the regional Indigenous language taught at the university) and then develop curricular resources that could be used in K-12 classrooms. We followed the guidance of our Elder, who encouraged learners to begin with the alphabet so that students can feel confident about the sounds and letters in the Ichishkíin language. Students thus began their work on the project by learning the Ichishkíin alphabet in the fall and developing resources that would help other learners in their own work to learn the alphabet (see Images 1 and 2). We shared a digital version of our Elder’s cassette tape labeled “Yakama ABCs” and asked students to listen to it several times to become familiar with and confident in their understanding of the alphabet. The cassette tape recording is a precious resource to Ichishkíin-speaking peoples, loved and used for decades among her early students who were learning our language. By bringing this resource into our classroom we connected students with generations of learners who have helped the Ichishkíin language to survive. On the recording, our Elder speaks the name of each letter in the alphabet, the sounds each letter makes, and examples of words that feature each sound. Notably, many of the example words are relational (birds, animals, plants, weather), connecting learners to important beings in traditional stories we mention below. Respectfully relating to more than human relatives who live and thrive in the lands around us would become a foundational lesson and theme to which we returned throughout the year.

Students created classroom resources as their skills in learning Ichishkíin developed, first featuring letters in the alphabet, then featuring key vocabulary words, then featuring complete sentences. Throughout the year, we paired this work with cultural teachings, including reading and discussing walsákt (traditional stories, also referred to as legends) from a book of legends that our Elder had gathered from her Elders, transcribed into English, and published as a classroom resource project in the 1970s (Beavert 1974; Beavert, Jacob, and Jansen 2021). Students enjoyed reading and discussing walsákt with our Elder and among each other; non-Yakama students enjoyed sharing how their own Tribal teachings related to the lessons within Yakama cultural teachings, a kinship building practice that supported our Elder’s vision for helping students relate to and connect with one another in meaningful ways. Students from non-Ichishkíin speaking Tribal Nations understood our Elder’s intention that they could use their work in our class as a training ground to support their future work to learn and sustain their own Indigenous languages. As we all commented throughout the year, “If you can learn and do this curricular resource development with Ichishkíin, you can definitely do this with your own language!”

Our community faced deep grief and challenges when our beloved Elder Tux̱ámshish became ill with pneumonia and died in early February, not quite halfway through the school year. We slowed our pace of work, centered the values of love and care that are the foundation of our kinship systems, and, when we were ready, reached out to another trusted Elder and language expert, Túulhinch Roger Jacob, Jr., to help us finish the project. We planned a daylong gathering with Túulhinch to do final reviews and corrections of resources that students developed, with plans to publish the collection before the end of the school year. Our Elder was impressed with the beauty and creativity of the resources. However, proofreading Ichishkíin is a very labor-intensive process; it must be done by experts as there is no technology to help make it easier. We also struggled to make corrections and address formatting across multiple software platforms (Canva, Word, Adobe, etc.). It took several months longer than expected, but with the grace and patience of Túulhinch, as well as a Yakama student, Faith Jacob, and a generous linguist with expertise in Ichishkíin, Joana Jansen, we were able to complete the project and publish the collection of resources on our program’s webpage, https://blogs.uoregon.edu/sapsikwala/ichishkiin-resources.

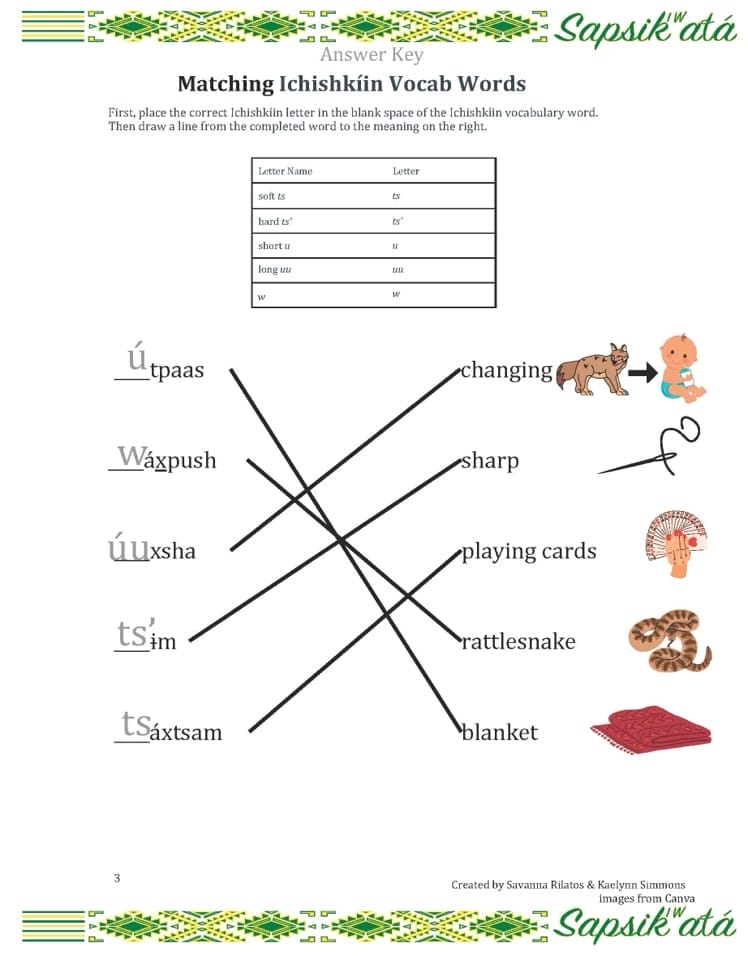

Images 1 and 2: Sample worksheet and answer key students created to help Ichishkíin learners.

These examples illustrate how our students’ work centers kinship and important cultural teachings while also highlighting the power of relationality. For example, in Images 1 and 2, students include relatives from two Yakama walsákt (Beavert, Jacob, and Jansen 2021). For the vocabulary word teaching long uu, úuxsha, students featured a verb that is illustrated with Spilyáy (legendary coyote) changing into a baby, a key moment in the walsákt “Spilyáy Breaks the Dam,” when Spilyáy the trickster uses his wittiness and brilliance to bring about the possibility of setting núsux (salmon) free so that the people may end their hunger and flourish. For the vocabulary word teaching about the letter w, students featured wáxpush (rattlesnake), an important teacher in the walsákt “Rattlesnake and Eel,” in which lessons about hospitality, kindness, and drawing from the strength of one’s identity shaped by our lands and waters are particularly important. By choosing these important relatives to feature in their worksheet, students demonstrated that they continued to carry the lessons of walsákt with them and to create a resource encouraging future learners to do so as well.

Benefits of the Project

Honoring the foundational practices for this project were important: Elder teachings, storytelling, understanding cultural values, and intergenerational learning. Students gained insight and a sense of responsibility to make meaning of embedded teachings and transmission of cultural values, ethical lessons, spiritual beliefs, and relationships between human and more than human relatives from stories and legends. Supporting language learning demands a multifaceted approach acknowledging traditional practices of fostering immersion, learning with Native language speakers, actively engaging in Native language practice, and encouraging peer-mentor support. A supportive, safe environment allowed students to be creative, build and strengthen their language skills, and understand how to access material to meet the needs of students and Tribal communities.

Developing language materials benefited students by building a foundation of effective ways to learn the Ichishkíin alphabet, vocabulary, and grammar, honoring the teachings of Elders, and strengthening their confidence to engage in language teaching. A relational approach to language learning included bringing in an Elder mentor-Native language teacher to meet with students, fostering interaction, enhancing language learning, and supporting cultural understanding. Watching students interact and learn with an Elder mentor provided a deeper meaning of language learning. Students were respectful with their interactions, quiet as they listened to the feedback, and displaying a level of comfort with pronunciation of the Ichishkíin language and development of language material, which included bingo, crossword puzzles, children’s storybooks, and flash cards. Our Elder mentor was supportive and encouraging with each student as learning to develop language learning material differs from speaking and the pronunciation of the Ichishkíin language. As our Elder mentor provided feedback on the beautiful work created, there was laughter, mutual respect, honoring the work of both contributing to the emerging work. Starting with foundational components of the language, students experienced confidence in comprehension and pronunciation, allowing for progression toward more complex concepts.

The unique learning needs of our Native students required us to honor traditional practice–learning through doing. Listening to the pronunciation in person provides a way of learning where there is shared knowledge and insight to cultural nuances, tone of voice, or expressions not always taught from a textbook. As we sat watching the interaction between Elder mentor and student, we observed facial expressions such as smiles, head nods, eye contact, and body language that demonstrated curiosity, understanding, and happiness–all contributing to student confidence, cultural connection, and the transference of Indigenous knowledge.

By creating educational materials, students were further engaged and gifted the opportunity to deepen their understanding of what it means to be an educator as well as equipping them with practical tools to support language preservation for their classrooms and communities. From our Elder’s teachings we created safe and encouraging space and place grounded with cultural values and practices such as community, relationships, respect, kinship, and mentorship. Intuitively they began to step into the roles of mentors, community leaders, and advocates for preserving language and culture, carrying forward the ongoing work to ensure accessibility to language material for all learners.

The collaboration among students and Elders within this project was crucial, as it enhanced students with a wider understanding in the Ichishkíin language, enabling a transfer of knowledge to their own Tribal languages and the languages of the students they may serve from other Indigenous Nations, depending on where they find themselves teaching. By working closely with Elders and using culturally sustaining teaching practices, students were immersed in an authentic learning environment that pushed linguistic and cultural fluency to the front. Learning from an Elder’s recorded teachings and conversing about traditional stories invested students to connect language acquisition with their own Tribal identity, strengthening the importance of oral traditions and the transfer of intergenerational knowledge. This intergenerational exchange reinforced the magnitude of relational learning, where knowledge passes through shared experience alongside written or state-sanctioned formal instruction. Working with Elders strengthened students’ respect for their role in language preservation, ensuring that efforts in revitalization are rooted in the values and teachings of those who came before them.

Centering Indigenous knowledge is vital for language learning as it creates a foundation of relationships, relationality, respect, and honoring of Elder teachings and directly connects language to cultural identity. With each lesson and activity, students further built their skills, providing a foundation for the student teacher to gain confidence through active participation. It also supported a healthy lifepath and sustainable futures through strengthening identities, cultural connections, and belonging. Indigenous knowledge systems are interconnected with the Yakama languages and create a pathway for preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge, traditional practices, ceremony, medicine, stories, and community values. Native student teachers acquired several skills and abilities such as learning by doing, an increased ability to contextualize lessons and activities based on student and community needs and culture, and the implementation of culturally responsive and sustaining instruction that supports community language revitalization efforts. Through active participation in developing language learning materials, students began to foster agency, which provided a sense of self-confidence within their own communities and workplaces. Developing Native language learning materials for our own communities, classrooms, and Tribes calls for an understanding of the local dialect and everyday language use, which then can be incorporated into materials for Native language learners.

Conclusion

Education often takes place in schools that privilege settler logics and priorities, rather than honoring Indigenous knowledges. Thus, in our experience, Indigenous education generally, and language revitalization in particular, are often filled with experiences of making do. While this can sometimes feel challenging, we note that when our work is grounded in a commitment to community and surrounded by the love and care of kinship that our Elders remind us are most important, we find deep joy and success in our work. These lessons are critical for all educators and students, particularly in challenging times. We hope that our project offers a hopeful and helpful example of how this work can be carried out. We are pleased with the gifts our students continue to create and share with us.

We are so inspired by the ways that beginning language learners have the creativity and love to lead the way in creating important, helpful resources to support the revitalization of Ichishkíin and to sustain important cultural teachings that are the strength and backbone of our Indigenous education systems. We hope readers also find joy and inspiration in learning about our project that sustains community cultural life.

Michelle M. Jacob (Yakama) loves imagining and working toward a future in which kindness, fierceness, and creativity saturate our lives and institutions in delicious and inviting ways. Jacob is an enrolled member of the Yakama Nation and is Professor of Indigenous Studies and Co-Director of the Sapsik’ʷałá Program at the University of Oregon.

Leilani Sabzalian (Alutiiq) is an Associate Professor of Indigenous Studies in Education and Co-Director of the Sapsik’ʷałá Program at the University of Oregon. Sabzalian’s heartwork is to support the next generation of Indigenous educators to become teachers within their communities and to create more just and humanizing spaces for Indigenous students.

Haeyalyn Muniz (Jicarilla Apache) is a PhD candidate in the Critical and Sociocultural Studies in Education Program at the University of Oregon. She serves as a mentor and program support with the Sapsik’ʷałá Program and works collaboratively with the Sapsik’ʷałá’s Grow Your Own program.

Regan Anderson (non-Native) works with Northwest Indigenous Language Institute as an Ichishkíin Language Instructor and teacher trainer at University of Oregon. She is also a Community Outreach Coordinator focused on babies and families at the Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit, Yakama Nation Language Program. Across her work and in her life, she strives to support families, including her own, in daily language use and in raising babies as first-language speakers.

Jon Caponetto (Burns Paiute) is a PhD student in the Critical and Sociocultural Studies in Education program at the University of Oregon. His research centers on the experiences of Indigenous and underrepresented college students navigating higher education institutions.

Works Cited

Anderson, Regan. 2019. Supporting Community Goals for Indigenous Language Revitalization in the Language Education Classroom. In On Indian Ground: The Northwest, eds. Michelle M. Jacob and Stephany RunningHawk Johnson. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing Inc., 233-44.

Anderson, Regan. 2022. K’aaw Natash Wa Chɨ́myanashma Shapáttawax̱sha ku Sápsikw’asha Myánashma ’We Are the Parents Raising and Teaching Children’: Raising Yakama Babies and Language Together. PhD Dissertation. University of Oregon.

Beavert, Virginia. 1974. The Way It Was: Anaku Iwacha: Yakima Legends. Yakima: Franklin Press and the Consortium of Johnson O’Malley Committees of Region IV, State of Washington.

Beavert, Virginia. 2017. The Gift of Knowledge = Ttnúwit Átawish Nchʼinchʼimamí: Reflections on Sahaptin Ways, ed. Janne L. Underriner. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Beavert, Virginia, Michelle M. Jacob, and Joana W. Jansen, eds. 2021. Anakú Iwachá: Yakama Legends and Stories, 2nd ed. Seattle: The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, in association with the University of Washington Press.

Greenwood, Margo. 2016. Language, Culture, and Early Childhood: Indigenous Children’s Rights in a Time of Transformation. Canadian Journal of Children’s Rights/Revue canadienne des droits des enfants. 3.1:16-31.

Henn, Danielle. 2018. A Pedagogy of Making Do. Journal of Folklore and Education. 5.2:161-69, https://jfepublications.org/article/a-pedagogy-of-making-do.

Hermes, Mary, Megan Bang, and Ananda Marin. 2012. Designing Indigenous Language Revitalization. Harvard Educational Review. 82.3:381-402.

Hoffman, Karen Ann. 2021. Written in Beads: Storytelling as Transmission of Haudenosaunee Culture. Journal of Folklore and Education. 8:30-8, https://jfepublications.org/article/written-in-beads.

Holmes, Amanda and Sara Tolbert. 2020. Relational Conscientization Through Indigenous Elder Praxis: Renewing, Restoring, and Re-storying. In Towards Critical Environmental Education, eds. Aristotelis S. Gkiolmas and Constantine D. Skordoulis. Switzerland: Springer Nature, 113–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50609-4_8,

Igari, Kaity Cassio, Juliana Cantarelli Vita, Jack Flesher, Cameron Armstrong, Skúli Gestsson, and Patricia Shehan Campbell. 2020. Let’s stand together, rep my tribe forever: Teaching toward Equity through Collective Songwriting at the Yakama Nation Tribal School. Journal of Folklore and Education. 7:65-78, https://jfepublications.org/article/lets-stand-together-rep-my-tribe-forever.

Jacob, Michelle M. 2013. Yakama Rising: Indigenous Cultural Revitalization, Activism, and Healing. Tucson: University of Arizona Press

Jacob, Michelle M., Emily West Hartlerode, Jennifer R. O’Neal, Janne Underriner, Joana Jansen, and Kelly M. LaChance. 2018. Placing Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge at the Center of Our Research and Teaching. Journal of Folklore and Education. 5.2:123-41, https://jfepublications.org/article/placing-indigenous-traditional-ecological-knowledge.

Jacob, Michelle M. and Leilani Sabzalian. 2022. Reclaiming Indigenous Kinship in Education: Lessons from the Sapsik’ʷałá Program. NEOS: A Publication of the Anthropology of Children and Youth Interest Group. 14.2:1–7.

Jansen, Joana Worth. 2010. A Grammar of Yakima Ichishkíin/Sahaptin. PhD Dissertation. University of Oregon.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina and T. L. McCarty. 2025. “To Remain an Indian”: Lessons in Democracy from a Century of Native American Education, 2nd ed.. New York: Teachers College Press.

McCarty, Teresa and Tiffany Lee. 2014. Critical Culturally Sustaining/Revitalizing Pedagogy and Indigenous Education Sovereignty. Harvard Educational Review. 84.1:101–24. doi:10.17763/haer.84.1.q83746nl5pj34216.

Norman, Dennis K. and J. P. Kalt, eds. 2015. Universities and Indian Country: Case Studies in Tribal-Driven Research. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Porter, Maureen K. and Nik Cristobal. 2018. Cultivating Aloha ‘āina Through Critical Indigenous Pedagogies of Place. Journal of Folklore and Education. 5.1-2:199-218, https://jfepublications.org/article/cultivating-aloha-aina.

Sapsik’ʷałá Teacher Education Program. 2024. Ichishkíin Resources, https://blogs.uoregon.edu/sapsikwala/ichishkiin-resources.

Sutterlict, Gregory. 2022. MIIMAWÍT: Our Ways, Our Language, Our Children, Our Land. PhD Dissertation. University of Oregon.

Topkok, Sean Asiqłuq 2018. Supporting Iñupiaq Arts and Education. Journal of Folklore and Education. 5.1:100-11, https://jfepublications.org/article/supporting-inupiaq-arts-and-education.

Tuck, Eve, Haliehana Stepetin, Rebecca Beaulne-Stuebing, and Jo Billows. 2022. Visiting as an Indigenous Feminist Practice. Gender and Education. 35.2:144–55. doi:10.1080/09540253.2022.2078796.

URLs

Blog https://blogs.uoregon.edu/sapsikwala/ichishkiin-resources